Front Note

I continue Oriana Fallaci’s questions 26 to 47, and Indira Gandhi’s answers to them. In this segment, Indira had talked about her personal relationships with her father Jawarhalal Nehru, mother Kamala, mentor Mahatma Gandhi, husband Feroze Gandhi and son Rajiv. The dots, wherever they appear, are as in the original.

Interview Proper

“Oriana: We didn’t want to hurt you.

Indira: I know. I repeat, I understand. But you must also understand us – always undervalued, underestimated, not believed. Even when we believed, you didn’t believe us. You said, ‘How is it possible to fight without violence?’ But without violence we obtained freedom. You said, ‘How is it possible for democracy to work with an illiterate people who are dying of hunger?’ But with that people we made a democracy work. You said, ‘Planning is something for communist countries; democracy and planning don’t go together!’ But, with all the errors we committed, our plans succeeded. Then we announced that there’d be no more starvation in India. And you responded, ‘Impossible. You’ll never succeed!’ Instead we succeeded; today in India no one dies of hunger any more; food production far exceeds consumption. Finally we promised to limit the birth rate. And this you really didn’t believe; you smiled scornfully. Well, even in this things have gone well. The fact is that we have grown by over seventy millions in ten years, but it’s also true that we have grown less than many other countries, including the countries of Europe.

Oriana: Often through dreadful methods, like the sterilization of men. Do you approve of that, Mrs. Gandhi?

Indira: In India’s distant past, when the population was low, the blessing given a woman was, ‘May you have many children.’ Most of our epics and literature stress this wish, and the idea that a woman should have many children hasn’t declined. I myself, in my heart, say that people should have all the children they want. But it’s a mistaken idea, like many of our ideas that go back thousands of years, and it must be rooted out. We must protect families, we must protect children, who have inalienable rights and should be loved, should be taken care of physically and mentally, and should not be brought into the world only to suffer. Do you know that, until recently, poor people brought children into the world for the sole purpose of making use of them? But how can you change, by force or all of a sudden, an age-old habit? The only way is to plan births, by one means or another. And the sterilization of men is one method of birth control. The surest, most radical method. To you it seems dreadful. To me it seems that, properly applied, it’s by no means dreadful. I see nothing wrong in sterilizing a man who has already brought eight or ten children into the world. Especially if it helps those eight or ten children to live better.

Oriana: Have you ever been a feminist, Mrs. Gandhi?

Indira: No, never. I’ve never had the need to; I’ve always been able to do what I wanted. On the other hand, my mother was. She considered the fact of being a woman a great disadvantage. She had her reasons. In her day women lived in seclusion – in almost all Indian states they couldn’t even show themselves on the street. Muslim women had to go out in purdah, that heavy sheet that covers even the eyes. Hindu women had to go out in the doli, a kind of closed sedan chair like a catafalque. My mother always told me about these things with bitterness and rage. She was the oldest of two sisters and two brothers, and she grew up with her brothers, who were about her age. She grew up, to the age of ten, like a wild colt, and then all of a sudden that was over. They had forced on her her ‘woman’s destiny’ by saying, ‘This isn’t done, this isn’t good, this isn’t worthy of a lady.’

At a certain point the family moved to Jaipur, where no woman could avoid the doli or purdah. They kept her in the house from morning to night, either cooking or doing nothing. She hated doing nothing, she hated to cook. So she became pale and ill, and far from being concerned about her health, my grandfather said, ‘Who’s going to marry her now?’ So my grandmother waited for my grandfather to go out, and then she dressed my mother as a man and let her go out riding with her brothers. My grandfather never knew about it, and my mother told me the story without a smile. The memory of these injustices never left her. Until the day she died, my mother continued to fight for the rights of women. She joined all the women’s movements of the time; she stirred up a lot of revolts. She was a great woman, a great figure. Women today would like her immensely.

Oriana: And what do you think of them, Mrs. Gandhi? Of their liberation movement, I mean.

Indira: I think it’s good. Good. Because, you see, until today the rights of people have always been put forward by a few individuals acting in the name of the masses. Today instead of people no longer want to be represented; each wants to speak for himself and participate directly – it’s the same for the Negroes, for the Jews, for women. So not only Negroes and Jews, but also women are part of a great revolt of which one can only approve. Women sometimes go too far, it’s true. But it’s only when you go too far that others listen. This is also something I’ve learned from experience. Didn’t they perhaps give us the vote because we went too far? Yes, in the Western world, women have no other choice. In India, no. And I’ll explain the reason. It’s a reason that also has to do with my own case. In India women have never been a hostile competition with men – even in the most distant past, every time a woman emerged as a leader, perhaps as a queen, the people accepted her. As something normal and not exceptional. Let’s not forget that in India the symbol of strength is a woman; the goddess Shakti. Not only that – the struggle for independence here has been conducted in equal measure by men and by women. And when we got our independence, no one forgot that. In the Western world, on the other hand, nothing of the kind has ever happened – women have participated, yes, but revolutions have always been made by men alone.

Oriana: Now we come to the personal questions, Mrs. Gandhi. Now I’m ready to ask them. And here’s the first: Does a woman like you find herself more at ease with men or with women?

Indira: For me it’s absolutely the same – I treat one and the other in exactly the same way. As persons, that is, not as men and women. But, even here, you have to consider the fact that I’ve had a very special education, that I’m the daughter of a man like my father and a woman like my mother. I grew up like a boy, also because most of the children who came to our house were boys. With boys I climbed trees, ran races, and wrestled. I had no complexes of envy or inferiority toward boys. At the same time, however, I liked dolls. I had many dolls. And you know how I played with them? By performing insurrections, assemblies, scenes of arrest. My dolls were almost never babies to be nursed but men and women who attacked barracks and ended up in prison. Let me explain. Not only my parents but the whole family was involved in the resistance – my grandfather and grandmother, my uncles and aunts, my cousings of both sexes. So ever so often the police came and took them away, indiscriminately. Well, the fact that they arrested both my father and mother, both my grandfather and grandmother, both an uncle and an aunt, made me accustomed to looking on men and women with the same eyes, on an absolute plane of equality.

Oriana: And then there’s that story about Joan of Arc, isn’t there?

Indira: Yes, it’s true. It’s true that Joan of Arc was my dream as a little girl. I discovered her toward the age of ten or twelve, when I went to France. I don’t remember where I read about her, but I recall that she immediately took on a definite importance for me. I wanted to sacrifice my life for my country. It seems like foolishness and yet…what happens when we’re children is engraved forever on our lives.

Oriana: Yes indeed. And I’d like to understand what it is that’s made you what you are, Mrs. Gandhi.

Indira: The life I’ve had, the difficulties, the hardships, the pain I’ve suffered since I was a child. It’s a great privilege to have led a difficult life, and many people in my generation have had this privilege – I sometimes wonder if young people today aren’t deprived of the dramas that shaped us…If you only knew what it did to me to have lived in that house where the police were bursting in to take everyone away! I certainly didn’t have a happy and serene childhood. I was a thin, sickly, nervous little girl. And after the police came, I’d be left alone for weeks, months, to get along as best I could. I learned very soon to get along by myself. I began to travel by myself, in Europe, when I was eight years old. At that age I was already on the move between India and Swizerland, Switzerland and France, France and England. Administering my own finances like an adult.

People often ask me: Who has influenced you the most? Your father? Mahatma Gandhi? Yes, my choices were fundamentally influenced by them, by the spirit of equality they infused in me – my obsession for justice comes from my father, who in turn got it from Mahatma Gandhi. But it’s not right to say that my father influenced me more than others, and I wouldn’t be able to say whether my personality was formed more by my father or my mother or the Mahatma or the friends who were with us. It was all of them; it was a complete thing. It was the very fact that no one ever imposed anything on me or tried to impose himself on the others. No one ever indoctrinated me. I’ve always discovered things for myself, in marvelous freedom. For instance, my father cared very much about courage, physical courage as well. He despised those who didn’t have it. But he never said to me, ‘I want you to be courageous.’ He just smiled with pride every time I did something difficult or won a race with the boys.

Oriana: How much you must have loved that father!

Indira: Oh, yes! My father was a saint. He was the closest thing to a saint that you can find in a normal man. Because he was so good. So incredibly, unbearably good. I always defended him, as a child, and I think I’m still defending him – his policies at least. Oh, he wasn’t at all a politician, in no sense of the word. He was sustained in his work only by a blind faith in India – he was preoccupied in such an obsessive way by the future of India. We understood each other.

Oriana: And Mahatma Gandhi?

Indira: A lot of mythology arose after his death. But the fact remains that he was an exceptional man, terribly intelligent, with tremendous intuition for people, and a great instinct for what was right. He said that the first president of India ought to be a harijan girl, an untouchable. He was so against the class system and the oppression of women that an untouchable woman became for him the epitome of purity and benediction. I began to associate with him when he came and went in our house – together with my father and mother he was on the executive committee. After independence I worked with him a lot – in the period when there were the troubles between Hindus and Muslims, he assigned me to take care of the Muslims. To protect them. Ah, yes, he was a great man. However…between me and Gandhi there was never the understanding there was between me and my father. He was always talking of religion…He was convinced that was right…The fact is, we young people didn’t agree with him on many things.

Oriana: Let’s go back to you, Mrs. Gandhi, to your history as an unusual woman. Is it true that you didn’t want to get married?

Indira: Yes. Until I was about eighteen, yes. But not because I felt like a suffragette, but because I wanted to devote all my energies to the struggle to free India. Marriage, I thought, would have distracted me from the duties I’d imposed on myself. But little by little I changed my mind, and when I was about eighteen, I began to consider the possibility of getting married. Not to have a husband, but to have children. I always wanted to have children – if it had been up to me, I would have had eleven. It was my husband who wanted only two.

And I’ll tell you something else. The doctors advised me not to have even one. My health was still not good, and they said that pregnancy might be fatal. If they hadn’t said that to me, maybe I wouldn’t have got married. But that diagnosis provoked me, it infuriated me. I answered, ‘Why do you think I’m getting married if not to have children? I don’t want to hear that I can’t have children; I want you to tell me what I have to do in order to have children!’ They shrugged their shoulders and grumbled that perhaps if I were to put on weight that would protect me a little – being so thin, I would never succeed in remaining pregnant. All right, I said, I’ll put on weight. And I started having massages, taking cod-liver oil, and eating twice as much. But I didn’t even gain an ounce. I’d made up my mind that on the day the engagement was announced I’d be fatter, and I didn’t gain an ounce. Then I went to Mussoorie, which is a health resort, and I ignored the doctors’ instructions; I invented my own regime and gained weight. Just the opposite of what I’d like now. Now I have the problem of keeping slim. Still I manage. I don’t know if you realize I’m a determined woman.

Oriana: Ys, I’ve realized that. And, if I’m not mistaken, you even showed it by getting married.

Indira: Yes, indeed. No one wanted that marriage, no one. Even Mahatma Gandhi wasn’t happy about it. As for my father…it’s not true that he opposed it, as people say, but he wasn’t eager for it. I suppose because the fathers of only daughters would prefer to see them get married as late as possible. Anyway I like to think it was for that reason. My fiancé, you see, belonged to another religion. He was a Parsi. And this was something nobody could stand – all of India was against us. They wrote to Gandhi, to my fther, to me. Insults, death threats. Every day the postman arrived with an enormous sack and dumped the letters on the floor. We even stopped reading them; we let a couple of friends read them and tell us what was in them. ‘There’s a fellow who wants to chop you both into little pieces. There’s someone who’s ready to marry you even though he already has a wife. He says at least he’s a Hindu.’ At a certain point the Mahatma got into the controversy – I’ve just found an article he wrote in his newspaper, imploring people to leave him in peace and not be so narrow-minded. In any case, I married Feroze Gandhi. Once I get an idea in my head, no one in the world can make me change my mind.

Oriana: Let’s hope the same thing didn’t happen when your son Rajiv married an Italian girl.

Indira: Times have changed; the two of them didn’t have to go through the same anguish I did. One day in 1965 Rajiv wrote me from London, where he was studying, and informed me, ‘You’re always asking me about girls, whether I have a special girl, and so forth. Well, I’ve met a special girl. I haven’t proposed yet, but she’s the girl I want to marry.’ A year later, when I went to England, I met her. And when Rajiv returned to India, I asked him, ‘Do you still think about her in the same way?’ And he said yes. But she couldn’t get married until she was twenty-one, and until she was sure she’d like to live in India. So we waited for her to be twenty-one, and she came to India, and said she liked India, and we announced the engagement, and two months later they were husband and wife. Sonia is almost completely an Indian by now, even though she doesn’t always wear saris. But even I, when I was a student in London, often wore Western clothes, and yet I’m the most Indian Indian I know. If you only knew, for instance, how much I enjoy being a grandmother! Do you know I’m twice a grandmother? Rajiv and Sonia have had a boy and a girl. The girl was just born.

Oriana: Mrs. Gandhi, Your husband has now been dead for some years. Have you ever thought of remarrying?

Indira: No, no. Maybe I would have considered the problem if I’d met someone with whom I’d have liked to live. But I never met this someone and… No, even if I had met him, I’m sure I wouldn’t have got married again. Why should I get married now that my life is so full? No, no, it’s out of the question.

Oriana: Besides I can’t imagine you as a housewife.

Indira: You’re wrong! Oh, you’re wrong! I was a perfect housewife. Being a mother has always been the job I liked best. Absolutely. To be a mother, a housewife, never cost me any sacrifice – I savored every minute of those years. My sons…I was crazy about my sons and I think I’ve done a super job in bringing them up. Today in fact they’re two fine and serious men. No, I’ve never understood women who, because of their children, pose as victims and don’t allow themselves any other activities. It’s not at all hard to reconcile the two things if you organize your time intelligently. Even when my sons were little, I was working. I was a welfare worker for the Indian Council for Child Welfare. I’ll tell you a story. Rajiv was only four years old at that time, and was going to kindergarten. One day the mother of one of his little friends came to see us and said in a sugary voice, ‘Oh, it must be so sad for you to have no time to spend with your little boy!’ Rajiv roared like a lion: ‘My mother spends more time with me than you spend with your little boy, see! Your little boy says you always leave him alone so you can play bridge!’ I detest women who do nothing and they play bridge.

Oriana: So there was a long period in your life when you stayed out of politics. Did you believe in it anymore?

Indira: Politics…You see, it depends on what kind of politics. What we did during my father’s generation was a duty. And it was beautiful because its goal was the conquest of freedom. What we do now, on the other hand…Don’t think that I’m crazy about this kind of politics. It’s no accident that I’ve done everything to keep my sons out of it, and so far I’ve succeeded. After independence I retired immediately from politics. My children needed me, and I like my job as a social worker. I said, ‘I’ve done my share. Leave the rest to the others.’ I went back into politics only when it was clear that things weren’t going as they should have in my party. I was always arguing, I argued with everyone – with my father, with the leaders I had known since I was a child…and one day, it was in 1955, one of them exclaimed, ‘You do nothing but criticize! If you think you can correct things, correct them. Go ahead, why don’t you try?’ Well, I could never resist a challenge, so I tried. But I thought it was something temporary, and my father, who had never tried to involve me in his activities, thought so too. People who say it was her father who prepared her for the post of prime minister, it was her father who launched her, are wrong. When he asked me to help him, I really didn’t suspect the consequences.

Oriana: And yet everything began because of him.

Indira: Obviously. He was prime minister, and to take care of his home, to be his hostess, automatically meant to have my hands in politics – to meet people, to know their games, their secrets. It also meant to fall sooner or later into the trap of direct experience. And this came in 1957, a weekend when my father had to go north for a rally. I went with him, as always, and when we got to Chamba, we discovered that the lady who had charge of his schedule had also set up a meeting for him someplace else – for Monday morning. So if my father had given up the rally in Chamba, we’d have lost the elections in Chamba; if he gave up the one in the other city, which was near Pathan kot, we’d lose the elections there. ‘And if I went?’ I suggested. ‘If I spoke, and explained that you couldn’t be in two places at once?’ He answered it was impossible. I’d have had to cover three hundred miles of bad road through the hills. And it was already two o’clock Monday morning. So I said good night and murmured, ‘A pity, it seemed to me a good idea.’ At five-thirty, when I woke up, I found a note under the door. It was from my father. It said, ‘A plane will take you to Pathankot. From there it’s only three hourse by car. You’ll arrive in time. Good luck.’ I arrived in time and held the rally. It was a success and I was asked for others. That was the beginning of…everything.

Oriana: Were you still married at that time, or were you already separated?

Indira: But I always stayed married to my husband! Always, until the day he died! It’s not true that we were separated! Look, the truth is otherwise and…why not say it for once and for all? My husband lived in Lucknow. My father lived in Delhi, of course. So I shuttled between Delhi and Lucknow and…naturally, if my husband needed me on days when I was in Delhi, I ran back to Lucknow. But if it was my father who needed me, on the days when I was in Lucknow. And…yes, my husband got angry. And he quarreled. We quarreled. We quarreled a lot. It’s true. We were to equally strong types, equally pigheaded – neither of us wanted to give in. And…I like to think those quarrels made us better, that they enlivened our life, because without them we would have had a normal life, yes, but banal and boring. We didn’t deserve a normal, banal, and boring life. After all, ours had not been a forced marriage and he had chosen me…I mean he was the one to choose me rather than I choosing him…I don’t know if I loved him as much as he loved me when we became engaged but…Then love grew, in me as well, it became something great and…well, you must understand him!

It wasn’t easy for him to be my father’s son-in-law! It wouldn’t have been easy for anybody. Let’s not forget that he too was a deputy in Parliament! At a certain point, he gave in. He decided to leave Lucknow and live in Delhi, in my father’s house, with him and me. But, being a deputy in Parliament, how could he meet people in the house of the prime minister? He realized that right away, and so he had to find himself another small house, and this wasn’t convenient either. To be a little here and a little there, a little with us and a little alone.

Oriana: Mrs. Gandhi, have you ever had regrets? Were you ever afraid of giving in?

Indira: No. Never. Fear, any fear, is a waste of time. Like regrets. And everything I’ve done, I’ve done because I wanted to do it. In doing it, I’ve plunged in headlong, always believing in it. Whether when I was a child and fought the British in the Monkey brigade, or when I was a girl and wanted to have children, or when I was a woman and devoted myself to my father, making my husband angry. Each time I stayed involved all the way in my decision, and took the consequences. Even if I was fighting for things that didn’t concern India. Oh I remember how angry I was when Japan invaded China! I immediately joined a committee to collect money and medicines, I immediately signed up for the International Brigade, I plunged headlong into propaganda against Japan…A person like me doesn’t have fear first and regrets afterward.

Oriana: Besides, you haven’t made mistakes. There are those who say that, having won this war, no one will be able to dislodge you and you’ll stay in power for at least twenty years.

Indira: I instead haven’t the slightest idea how long I’ll stay, and I don7t even care to know, because I don’t care if I remain prime minister. I’m only interested in doing a good job as long as I’m capable and for as long as I don’t get tired. I’m certainly not tired – work doesn’t tire people, it’s getting bored that’s tiring.. But nothing lasts forever, and no one can predict what will happen to me in the near or distant future. I’m not ambitious. Not a bit. I know I’ll astonish everyone by talking like this, but it’s God’s truth. Honors have never tempted me and I’ve never sought them. As for the job of prime minister, I like it, yes. But no more than I’ve liked other work that I’ve done as an adult. A little while ago I said that my father was not a politician. I, instead, think I am. But not in the sense of being interested in a political career – rather in the sense that I think it necessary to strive to build a certain India, the India I want. The India I want, I’ll never tire of repeating, is a more just and less poor India, one entirely free of foreign influences. If I thought the country was already marching toward these objectives, I’d give up politics immediately and retire as prime minister.

Oriana: to do what?

Indira: Anything. As I told you, I fall in love with anything I do and I always try to do it well. And so? Being prime minister isn’t the only job in life! As far as I’m concerned, I could live in a village and be satisfied. When I’m not governing my country any more, I’ll go back to taking care of children. Or else I’ll start studying anthropology – it’s a science that’s always interested me very much, also in relation to the problem of poverty. Or else I’ll go back to studying history – at Oxford I took my degree in history. Or else…I don’t know, I’m fascinated by the tribal communities. I might busy myself with them.

Listen, I certainly won’t have an empty life! And the future doesn’t frighten me, even if it threatens to be full of other difficulties. I’m trained to difficulties; difficulties can’t be eliminated from life. Individuals will always have them, countries will always have them…The only thing is to accept them, if possible overcome them, otherwise to come to terms with them. It’s all right to fight, yes, but only when it’s possible. When it’s impossible, it’s better to stoop to compromise, without resisting and without complaining. People who complain are selfish. When I was young, I was very selfish, now not any more. Now I don’t get upset by unpleasant things, I don’t play the victim, and I’m always ready to come to terms with life.

Oriana: Mrs. Gandhi, are you a happy woman?

Indira: I don’t know. Happiness is such a fleeting point of view – there’s no such thing as continual happiness. There are only moments of happiness – from contentment to ecstacy. And if by happiness you mean ecstasy … Yes, I’ve known ecstasy, and it’s a blessing to be able to say it because those who can say it are very few. But ecstasy doesn’t last long and is seldom if ever repeated. If by happiness you mean instead an ordinary contentment, then yes – I’m fairly contented. Not satisfied – contented. Satisfied is a word I use only in reference to my country, and I’ll never be satisfied for my country. For this reasons I go on taking difficult paths, and between a paved road and a footpath that goes up the mountain, I choose the footpath. To the great irritation of my bodyguards.

Oriana: Thank you, Mrs. Gandhi.

Indira: Thank you. And best wishes. As I always say, I do not wish you an easy time, but I wish you that whatever difficulty you may have, you will overcome it.

New Delhi, February 1972.”

Additional Thoughts by Oriana Fallaci on Indira Gandhi

Additional Thoughts by Oriana Fallaci on Indira Gandhi

I shouldn’t omit the description Oriana Fallaci had presented, as a prelude to the interview setting. Thus, I provide the two paragraphs below, which appear before the interview proper.

“I met Indira Gandhi in her office in the government palace. The same office that had been her father’s – large, cold and plain. She was sitting, small and slender, behind a bare desk. When I entered, she got up and came forward to give me her hand, then sat down again and cut the preliminaries short by fixing me with a gaze that meant: Go ahead with the first question, don’t waste time, I really have no time to waste. She answered cautiously at first. Then she opened up like a flower and the conversation flowed along without obstacles, in mutual sympathy. We were together for more than two hours, and when the interview was over, she left the office to accompany me to the taxi waiting for me in the street. Along the corridors and going down the stairs, she held me by the arm, as though she had always known me and talked about this and that, responding with an absent-minded nod to the bows of officials. She looked tired that day, and all of a sudden I exclaimed, ‘Deep down I don’t envy you, and I shouldn’t like to be in your place.’ And she said, ‘The problem is not in the problems I have, it’s in the idiots around me. Democracy, you know…’ I now wonder what she meant by that unfinished phrase. And sometimes I ask myself whether she had, even then, a certain contempt for the system she represented and, years later, would overthrow.

Forty-eight hours later, having found some gaps in the interview, I wanted to see her again, but without standing on ceremony I went to her house, a modest bungalow that she shares with her sons Rajiv and Sanjay. No one is more accessible than Indira Gandhi when she is home, and you realize this in the morning when she receives people who come with petitions, protests, wreaths of flowers. I rang the bell, the secretary came to open the door, and I asked her if the prime minister could give me another half hour. The secretary answered, ‘Let’s see,’ then went away and came back with Indira. ‘Come, sit down, let’s have a cup of tea.’ We sat down in the living room opening on the garden and talked for another hour. Besides the things I asked her, she told me about her son Rajiv, who is married to an Italian girl and is a pilot for Air India, then of her younger son Sanjay, who is an automobile designer and still a bachelor. Finally she called a beautiful dark little boy who was playing on the lawn, and embracing him tenderly, murmured, ‘This is my grandchild; this is the man I love most in the world.’ It was a strange sensation to watch this very powerful woman embracing a child. It brought back to mind the injustice I spoke of, the solitude that oppresses women intent on defending their own destinies, their own dreams, their own mistakes.”

Coda

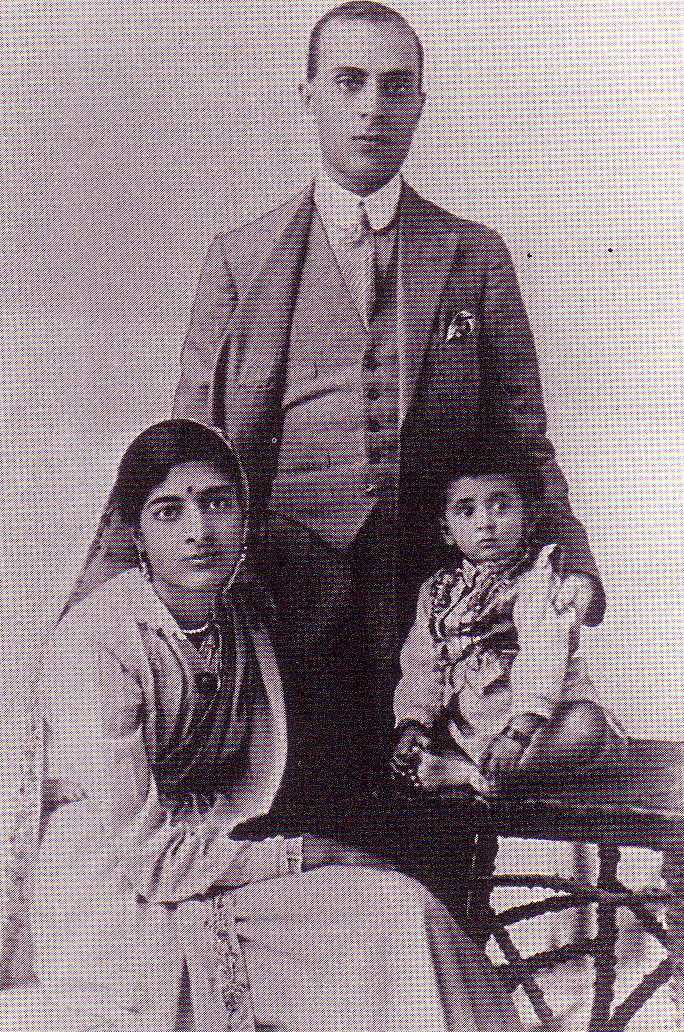

I have scanned three photos in which Indira Gandhi is featured. In one, she is seen with her parents, Jawarhalal Nehru and Kamala. The second photo was taken on her wedding ceremony to Feroze Gandhi (March 26, 1942). Indira’s father Nehru is seen at the left extreme. Her mother had died in 1936. In the third photo, Indira is seen with her two sons, two daughter in laws and two grandchildren (Rajiv-Sonia’s children). On to Indira’s right Rahul is seen, whom she had talked about as ‘the man I love most in the world’ to Oriana.

Oriana Fallaci had inferred that Indira had ‘a certain contempt for the system she represented’ (i.e, democracy). It had to be. While her father Nehru faced three general elections (1952, 1957 and 1962) during post-independent euphoria, when Indira took the reins that euphoria had evaporated after almost 20 years. Indira faced the situation of tackling the old codgers of the Congress Party (who basked in their ‘freedom fighter’ laurels), while the population of India increased tremendously. She faced four general elections (1967, 1971, 1977 and 1980), and was victorious in three and lost one in 1977. Even after splitting the Congress Party in 1969, Indira was successful in leading her party with 350 seats (1971) and 353 seats (1980) in general elections, almost in the range (361-371 sears) which her father was able to collect in 1951, 1957 and 1962 general elections with the euphoria wind behind his back.