A pioneer Eelam Tamil actress, dancer and singer

by Sachi Sri Kantha, April 19, 2021

As of now, I had profiled the careers of five Eelam Tamil women on this website.

Dr. Grace Rajamalar Barr Kumarakulasinghe (1908-2013) https://sangam.org/dr-grace-rajamalar-barr-kumarakulasinghe-1908-2013/

Dr. Siva Chinnatamby (1923-2000), https://sangam.org/dr-siva-chinnatamby-20-years-after-her-death/

Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu (1930-2001), https://sangam.org/dr-manorani-saravanamuttu/

Prof. Mano Sabaratnam (1931-2014), https://sangam.org/professor-mano-sabaratnam-1931-2014/

and Dr. Rajani Thiranagama (1954-1989), https://www.sangam.org/2010/09/Who_Killed_Rajani.php?uid=4071

Thavamani Devi, in her salad days

All five of these women were ‘doctors’; among whom four excluding Prof. Mano Sabaratnam, were physicians. The individual I profile here, Kathiresu Thavamani Devi belongs to a distinct category of talented artistes (an actress, dancer and singer). She became a household name for Indian movie fans in 1940s. In fact, she deserves to be tagged as the first Eelam Tamil woman who became a celebrity star of cinema medium.

Rebutting Misleading Information on Thavamani Devi

Thavamani Devi died 20 years ago on February 10, 2001, at the age of 76 years. The information available about her in the net is meager and conflicting. Thavamani Devi’s Wikipedia profile (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K._Thavamani_Devi) includes minimum material about her, citing what had appeared in my MGR series (https://sangam.org/mgr-remembered-part-10/). The Sakuntalai movie photo frame that appears in her entry is also erroneous. What is presented in the photo with M.S. Subbulakshmi is not Thavamani Devi, but T.A. Mathuram! In another popular website of a blogger ‘Andru Kanda Muham’ on Tamil movie stars, (https://antrukandamugam.wordpress.com/2015/05/25/thavamani-devi-k/)

misleading information is suggested that she may be of Sinhala origin – i.e., her mother might have been Sinhalese, even if her father was a Tamil. In reality, both her parents were from Jaffna. As she herself had stated in the Ananda Vikatan interview in 1992, Thavamani Devi’s maternal uncle Kathiravetpillai Balasingam (1876-1952) was a legislator in the Legislative Council of Ceylon (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K._Balasingam) during 1910s-1920s. Being fluent in Sinhala and singing Sinhalese songs, doesn’t make Thavamani Devi a Sinhalese.

In this profile, I provide details on Thavamani Devi, that I had gathered from reliable sources, including MGR’s autobiography. She is a native of Inuvil, Jaffna. As she was the first movie star to appear in a swim suit and perform in a bikini suit (a female Tarzan role) in Tamil movies, following the death of her father who lived with her in Chennai, Thavamani Devi became one of the early victims of ever prevalent casting couch seductions in Tamil movie industry in late 1940s/early 1950s. She was harassed and chased away from Chennai. Being a non-Indian native might have been a contributing factor.

MGR Gold Standard

When it comes to Tamil movies, M. G. Ramachandran (MGR, 1917-1987) serves as a polestar or one may suggest a gold standard by which careers of his contemporaries are measured. The heroines and other woman actresses who associated with MGR in stages and movies can be conveniently grouped in three categories.

Category 1 (1936-47): Those who were already stars, before MGR made it to the top. Examples are M.S. Subbulakshmi, T.R. Rajakumari, T.A. Maduram, P. Kannamba and P. Bhanumathi.

Category 2 (1947-55): Those who rose to the top rank, along with MGR. Examples are V.N. Janaki, Madhuri Devi, B.S. Saroja and Padmini.

Category 3: (since 1956): Those who gained in ranks by association with MGR after he became a superstar. Numerous to count.

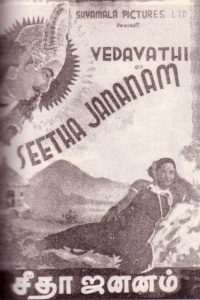

Seetha Jananam or Vedavathi (1941) movie poster

Among these, Thavamani Devi belongs to the first category. She acted in two of MGR’s movies. The first one was Seetha Jananam or Vedavathi (1941). While Thavamani Devi, aged 17, played the heroine role of Seetha, MGR (then aged 24) was an unemployed actor, and was offered a minor role as Indrajit (the son of King Ravana). This movie was released on Feb. 22, 1941. Two months prior to this date, Sakuthalai (1940) starring carnatic diva M.S. Subbulakshmi in the title role was released and became a big hit. In Sakunthalai too, Thavamani Devi played a recognizable role as Menaka. Though the running time of this movie is nearly 3 hours, unfortunately in the Youtube posted version of Sakunthalai which I had seen (2 hours and 32 min https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7AZAiQagTM), the segments in which Thavamani Devi appears had been chopped off. I had watched the videocassette version, before the origin of Youtube, with Thavamani Devi’s segments.

In his autobiography MGR had described the travails he faced to play the Indrajit role in Seetha Jananam, for which he was paid ONLY a paltry 25 rupees!! The director of the movie Raja Chandrasekhar (whom, MGR considered as one of his mentors) also wanted MGR to play the second role of Vishnu as well, with no additional pay. This MGR adamant in his demand, that he had to be paid additionally for his second role. Overruling MGR’s demand, his mentor had arranged another actor V.S. Mani for that Vishnu role. MGR had also expressed the agony he had to face with his mentor; as such, he even decided to quit the movies and trained himself to join the army, where the pay was 125 rupees per month for a rookie. Six years later, again Thavamani Devi was slated to play the villain (vamp) role in 30 year old MGR’s first hero role movie, Rajakumari (released on April 11, 1947). Though Telugu star K. Malathi was paired with MGR in this movie, Thavamani Devi had a noticeable presence in this movie as well. A Youtube clip of Thavamani Devi – MGR and T.S. Baliah scenes of about 9 min has been posted in 2017. The link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1MjJ1z2jko

An interview to Ananda Vikatan in 1992

Thavamani Devi in Vana Mohini (1941) movie

In an interview she had given to Ananda Vikatan in 1992, Thavamani Devi had looked back on her pioneering life between 1930s and 1940s. Translated excerpts follow:

“We then lived in Colombo. Our native place is near Jaffna. We belonged to Brahmin community. Father Kathiresu Subramaniam held the position of judge in Colombo. Uncle Balasingam held a ministerial position too. Our family was an educated one. My parents had five sons, and they had prayed for a girl in pilgrimage to many temples. As such, after my birth, I was named Thavamani Devi [literally meaning, a jewel born after penance]. Due to this, I was the pet of the family.

When I was in school, I had friendship with a guy named Udaiyappa. He was talented in singing and dancing. He taught me Tamil songs. Singing religious hymns and listening to Kittappa’s songs in gramophone, I gathered musical knowledge. Music tuition was arranged at home. I had memorized Kittappa’s songs like, ‘Dasaratha raja kumara…’ One day, in a class competition, I sang the song then popular in the Indian freedom movement. Home folks came to know about it and chided me saying ‘If you sing such songs in Colombo, and the British government comes to know, you may be arrested.’ Luckily, nothing of that sort happened.

I also learnt Sinhalese reading and writing, and could sing Sinhala songs as well. I got an opportunity to sing in Radio Ceylon, and was awarded the title ‘Ceylon Cuckoo’. When this news appeared in the newspapers, my relatives were upset stating that ‘Our family respect had been tarnished’, and my father had to tackle them with diligence. I became popular, when I danced in front of Lord Wavell [aka Archibald Percival Wavell, 1883-1950; he served as Commander in Chief, India in early 1940s.]. Around that time, M.K. Thyagarajah Bhagavathar and his troupe were visiting Ceylon for concerts. We attended that concert. As he resembled my late brother, my mother had felt an undeclared affection to him. Later, when my father visited him at the end of the concert, I also accompanied him. Bhagavathar greeted my father with the words, ‘Appa, please come in.’ Father was surprised too by such an endearing greeting. We invited Bhagavather to our home. I sang in front of him. Bhagavathar asked permission from my father, ‘Thangachi (Younger sister) is singing well. I’ll take her and make her a cinema star.’ Father didn’t like it, and subtly diverted that request.

When Bhagavathar’s concerts were held in Ceylon, his father [Krishnasamy] who had accompanied his son had died suddenly. Bhagavathar was keen in taking the remains to his native place (in Tamil Nadu). Transporting dead remains from country to country deserved tackling many administrative procedures and was a financial drain too. ‘I don’t worry, how much it will cost. For the last time, I had to show the remains of my father, to my mother. If I fail in this, there’s no meaning of me, being their son. He cried like a child and asked my father ‘Please help me’. Using his influence, my father was able to help in solving this issue by arranging the remains to be transported by boat, via Thanuskody port. Following this episode, families of Bhagavathar and Thavamani Devi became closer.”

Thavamani Devi continued her reminiscences.

“When I was around 13, the boss of Modern Theatres, T.R. Sundaram had heard about me and sent his assistant to sign a movie contract. My father first rejected. Somehow due to the persistence of that assistant, my father agreed. He gave an advance of 10,000 rupees too. We arrived at Tamil Nadu. We were given a house. On the first day, when I delivered the dialogue with passion, T.R. Sundaram was pleased. I was signed as heroine for ‘Sathi Ahalya’ movie. We were provided with all facilities and well looked after by T.R. Sundaram. Apart from the shooting days, no one – including Sundaram – bothered to visit us at home. We were pleased with that arrangement. After ‘Sathi Ahalya’, I received contracts for Shyam Sundar and Seetha Jananam. [Note by Sachi: Sathi Ahalya directed by T.R. Sundaram was the first movie for Modern Theatres and was released on March 10, 1937. To act in these movies, I travelled from Ceylon. All were good companies. After the death of my mother, and my father’s retirement, my father and I settled in Chennai.

T.R. Sundaram and my father had become close friends. To be free from the tension involved in cinema business, he played chess with my father. When Sundaram and my father settled down to talk or play chess, no one could be there. I wouldn’t even peep that side. One day, while he was playing chess, I went and solicited for an opportunity for P.U. Chinnappa to appear in the ‘Uttama Puthiran’ movie, I will never forget the scolding I received from him, for spoiling his game strategy! Simultaneously, I should also say that he did offer the chance to Chinnappa as well. [Note by Sachi: The Uttama Putthiran produced by the Modern Theatres, based on ‘The Man in the Iron Mask’, was released on Oct 24, 1940. Subsequently, it was also re-made with Sivaji Ganesan, by the Venus Pictures in 1958.]

During 1945-46, the Vana Mohini movie I acted did create grand stir in Indian movie world. The reason being, it was filmed in a forest, like Tarzan-style. I ran, jumped, fought and acted as an action heroine. The two piece dress I wore for that movie, raised hundreds of thousand eye brows. When Vana Mohini became a grand success, I was only 17. [Note by Sachi: Vana Mohini was released on Dec. 24, 1941, 10 months after Seetha Jananam, and Thavamani Devi’s memory had slipped here.] I received many movie contracts. I also got involved in producing my movie, ‘Vijaya’. Then only, I realized that a wave against me had been activated. There were threats – ‘Thavamani should be relieved from the contracts. If she was contracted and did act as a heroine, we wouldn’t allow to release that movie or stop it from running.’ One actor and two script writers were determined to chase me out with such threats. Because of this, all producers who had signed me faced difficulties.

There is a reason for such opposition. For some producers and directors, it is not enough for actresses to simply act. They need to accommodate every request. But, I acted only in the movies made by respectable companies. One producer offered me bangles made from expensive stones and salivated, ‘Thavamani, will you wear this? They are appropriate to your hands.’ I asked him, ‘Why you should give me such gift?’. ‘Just for that’, he smirked. I replied, ‘The fee you pay for my acting is more than enough.’ Another producer, amidst shooting asked me, ‘Why not join me for talk?’ I crossed him with the quip, ‘If you need that, you can talk here and now?’

I wanted to live respectably. But, due to wicked designs of my rivals, I lost many opportunities. Financing my own movie also became difficult. I lost my father as well. As such, I couldn’t return to Ceylon. I had to sell car and jewels. Even when I opted to conduct dance and music programs, there was opposition to that work as well. There was protest not to hold my program as Tiruchi Thevar hall. From many angles, I faced troubles and sorrows. At Chennai, I lived in a rented house. At night, in the backyard, I noted that bones were thrown to threaten me. There were curse items thrown in the yard, and the kolam decorations at the entrance were dismantled. From all angles, there was a ‘shadow war’ against me. Still, for 10 years I lived selling all my possessions. Finally, for mental peace, I went to Rameswaram.

Thavamani Devi and her husband, in Rameswaram

I stayed in an ashram at Rameswaram and visited the temple daily. One day, Shri Kodilingam Sastri came to know about this, and asked me ‘Amma, aren’t you, Thavamani?’ I said, ‘Yes’. He responded, ‘While we are living here, why you had to live in an ashram? We know your family for generations – and not for yesterday or today. Please come to live with my uncle.’

When we lived in Ceylon, the father of Kodilinga Sastri was our family’s consultant priest. From Rameswaram, he visited our house functions. As Kodilinga Sastri also had visited our house with his father, of course, I knew him well. Because of that intimate link, he invited me.

Kodilinga Sastri had married earlier, and had lost his wife. After learning about my troubles, Sastri’s uncle wanted to marry his nephew to me. He also politely solicited my consent. I agreed. Sastri and I got married in November 1962. After leaving cinema memories to past, now I live a spiritual life with happiness.”

Trendsetter and Filmography

Thavamani Devi was indeed a trend setter for women from elite class families to join the cinema world of India. In 1930s, cinema acting was frowned upon for elite class women. Only women of loose morals and disrepute were thought of doing such dancing and singing in front of camera for the pleasure of men. To quote a passage from analyst M.S. S. Pandian (who in turn had borrowed the lines from Tamil movie historian Aranthai Narayanan),

“elite politics made visiting cinema halls a taboo for ‘respectable’ women from upper caste/class families. If visiting cinema halls was a taboo, acting in films was unthinkable for them, Thavamani Devi, an actress who came from Ceylon to Madras to act in Modern Theatre productions, made an appeal in the 1930s that women from respectable families should give up their reluctance and act in films. Responding to this appeal, a Tamil magazine allegedly published her photo in a swimming costume and captioned it thus, ‘Thavamani Devi, an actress’ who has come from Ceylon to act as, chaste Akalya, appeals to women from [respectable] families to act in film” [Aranthai Narayanan 1981:115)

Thavamani Devi thwarted such misrepresentation of women’s skill and talent courageously. According to Film News Anandan’s directory of Tamil movies, a total of 11 movies featuring Thavamani Devi had been released between 1937 and 1949. The list is as follows:

Sathi Ahalya 1937 (Modern Theatres) – released March 10, 1937.

Sakunthalai 1940 (Royal Talkies – Chandraprabha Cinetone).

Shyam Sundar 1940 (Lakshmi Cinetone)

Krishna Kumar 1941 (Salem Sadana Films)

Vana Mohini 1941 (South Indian United Artiste Corporation)

Seetha Jananam or Vedavathi 1941 (Shyamala Pictures)

Bhaktha KaLathi 1945 (Padma Pictures)

Aravalli-Sooravalli 1946 (Southern Theatres)

Vidyapathi 1946 (Jupiter Pictures)

Rajakumari 1947 (Jupiter Pictures)

Natiya Rani 1949 (Bhaskar Pictures) – released Aug. 19, 1949.

Apart from these 11 movies, autobiography of director Ellis Dungan also includes a Telugu movie Valmiki (1945; Bama Films), directed by Dungan, in which Thavamani Devi is credited, with C.S.R. Anchaneyalu. Due to the troubles she had to face, her own film ‘Vijaya’ was left incomplete.

Considering the Second World War period, with prevailing rations and quotas on film reel distribution, 12 movie credits between 1937 and 1949 by Thavamani Devi is not insignificant. For comparison, between 1938 and 1945, M.S. Subbulakshmi acted only in 4 Tamil movies. Ellis Dungan directed only 12 movies between 1936 and 1950.

Among the 12 Thavamani Devi movies, negatives are preserved for at least for Sakuntalai and Rajakumari. I’m not sure about the negative availability for other 10 movies, in any film archives.

Coda

Though 80 years had passed, as of now, no cinema artiste of Eelam origin, had enjoyed the success Thavamani Devi had in Salem and Chennai for more than a decade from 1937 to late 1940s. Though not in equal rank, she had a recognizable role in the Sakuntalai (1940) movie, with Carnatic music greats M. S. Subbulakshmi and G.N. Balasubramaniam. Who would imagine that Thavamani Devi was paid in tens of thousand rupees for a heroine role as Seetha, when MGR was paid a measly 25 rupees for a minor role in Seetha Jananam movie in 1941? Furthermore, she was a big star on her own, when MGR had his first break as a hero in the Rajakumari (1947). Thavamani Devi was indeed an original talent, who stood up for decency and equal treatment of women in an industry long known for its shady dealings. She lost out for her conviction, but still remains a beacon, 20 years after her death.

Cited Sources

Ellis Dungan and Barbara Smik: A Guide to Adventure – an autobiography, Dorrance Publishing Co, Pittsburgh, 2001.

MGR: Naan Yean Piranthen (part 1), Kannadhasan Pathippagam, Chennai, 2014.

Aranthai Narayanan: Thamizh Cinemavin Kathai, 3rd ed., New Century Book House, Chennai, 2008.

M.S.S. Pandian: Tamil cultural elites and cinema – Outline of an argument. Economic & Political Weekly, Apr 13, 1996; 31(15): 950-955.

Bismi Parinaman: Oru kuyilin kumural [Cry of a Cuckoo], Ananda Vikatan Pokkisham Oct 17, 2012 (reprint from Aug. 2, 1992).

Thambyayah Thevathas: Thavamani Devi, In: Ilankai Thiraiyulaha Munnodikal – Pioneers of Sri Lankan Cinema, Kanthalagam, Chennai, 2001, pp. 109-113.

A post script: I add another fact, which was inadvertently omitted. According to MGR’s autobiography, he was paid only 2,500 rupees for his first hero-role, in ‘Rajakumari’ movie. This sum was paid in 200 rupees per month in installments.

It is amazing to know about an artiste like Thavamani Devi who was far ahead of her time in demanding and getting gender equality in an industry which is even today unfair for women.