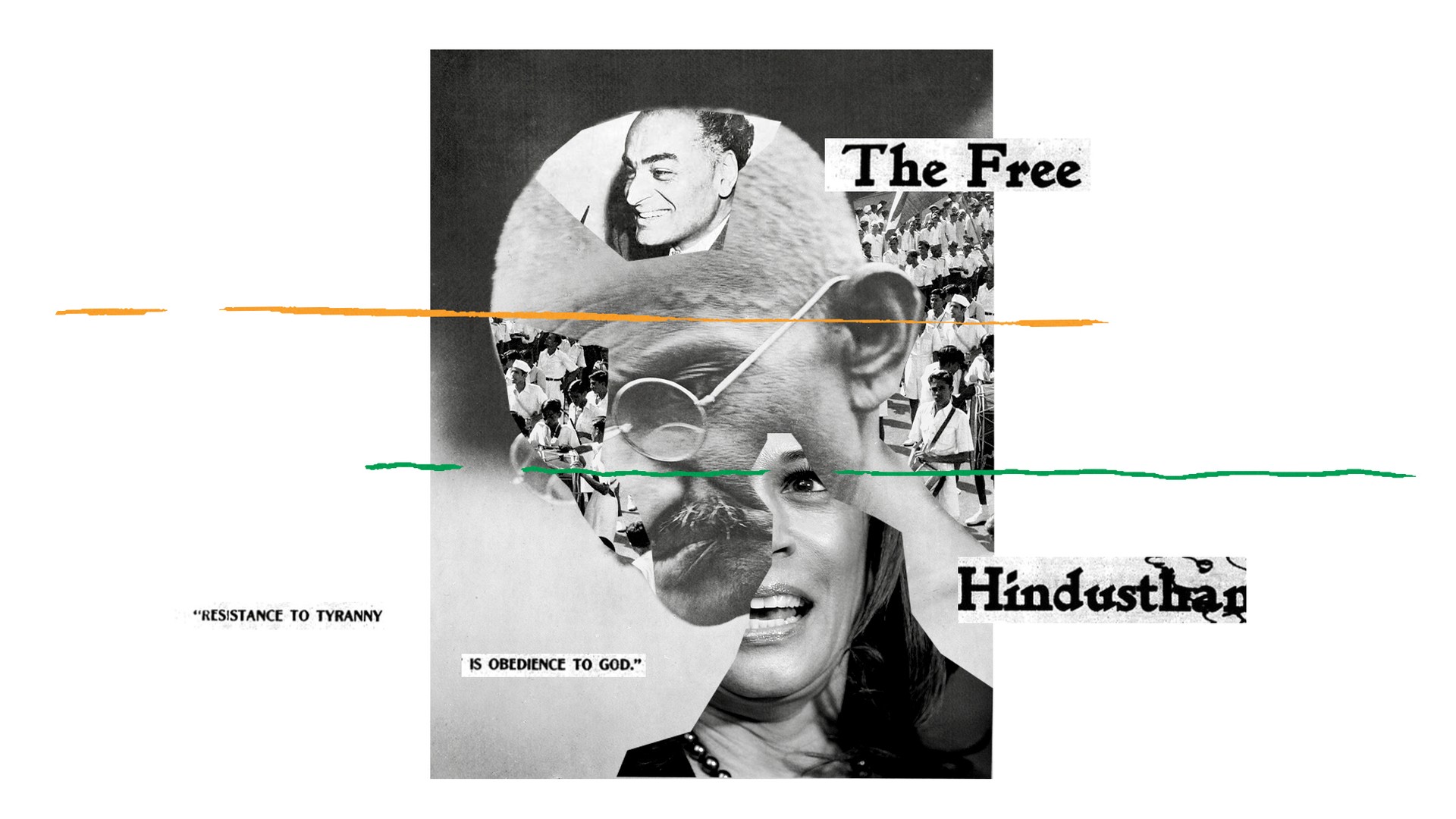

Long before the Democratic vice-presidential candidate became a national figure, India played a role in American politics

by Dinyar Patel, The Atlantic, New York, October 2020

In a few weeks, the United States might elect its first vice president of Indian heritage. Kamala Harris’s rise mirrors the fortunes of Indian Americans, a wildly successful community whose high levels of education and income have led to it being dubbed “the other 1 percent.”

In a few weeks, the United States might elect its first vice president of Indian heritage. Kamala Harris’s rise mirrors the fortunes of Indian Americans, a wildly successful community whose high levels of education and income have led to it being dubbed “the other 1 percent.”

Harris’s name on the ballot, combined with President Donald Trump’s strong relations with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, have put Indian Americans—a much smaller contingent than other prominent minority groups—in the spotlight this year, and both Republicans and Democrats are vying for their votes. It is tempting, then, to think that this rise to prominence has been sharp and sudden.

In fact, Indian American political influence has deep historical roots. Well before the first wave of mass Indian immigration in the 1960s, the U.S. played a significant role in India’s independence movement against British colonial rule. For colonized Indians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. represented a compelling alternative of democracy and relative equality (they quickly realized that this did not extend to African Americans). Several Indian political leaders such as B. R. Ambedkar and J. P. Narayan studied in American universities or embarked on prolonged visits. Many Americans, meanwhile, sympathized with India’s anti-colonial movement and saw parallels with their own republic’s struggle for existence.

Read: Why Joe Biden picked Kamala Harris

Only a few sources—a confidential British intelligence report, a sheaf of surviving letters, and a trail of newspaper articles—help us reconstruct the life of the first individual, George Freeman, an Irishman who emigrated from London in the late 19th century. According to the intelligence report, his hatred of the British empire was so intense that, having left English soil, he changed his last name to Freeman from Fitzgerald. After a few years of agitating against the empire in Canada, he migrated to New York, where he joined the Clan na Gael, an Irish republican organization, and wrote articles criticizing the British empire for the New York Sun.

What precisely drew Freeman to Indian political affairs is unclear. American newspapers at the time cataloged grim news from South Asia—famine and plague—which might have sparked his interest. In 1897, Freeman struck up a lengthy correspondence with Dadabhai Naoroji, the first major Indian-nationalist leader, who was then based in London, one of the very first instances of anti-colonial cooperation between an Indian and an American.

With jingoism ascendant after the Spanish-American War of 1898, and the Stars and Stripes fluttering over the Philippines and Puerto Rico, Freeman took Naoroji’s writings, which documented how British rule had devastated India, and mailed them across the U.S.: to anti-imperialists from Boston to Nebraska, U.S. senators, public libraries, and universities.

Through an Omaha friend, he even sent Naoroji’s writings to William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1900, who applied Naoroji’s ideas—that imperialism caused a “drain of wealth” that placed millions of colonial subjects on the cusp of famine—to the American postwar context. In newspaper articles and speeches, Bryan argued that “England’s policy is our warning.” He later met Freeman in New York and told him of “the instruction he had derived from reading” Naoroji’s pamphlets. India, therefore, played a minor role in the 1900 presidential campaign.

Freeman became, in the words of a nervous British intelligence officer based in India, “regarded by Indians in New York as the real leader of the anti-British movement.” He put new Indian arrivals in touch with Irish republicans and coordinated shipments of fiery revolutionary literature to India. During the First World War, he took part in an elaborate plot to smuggle German weapons into India, but thereafter slipped out of the historical record. One of his last public statements appeared in the Amrita Bazar Patrika in 1922, where he regretted never being able to visit the country whose freedom he had spent so much of his life championing.

Read: The anointment of Kamala Harris

As Freeman retreated into the shadows, yet another immigrant who would have an outsized impact on the Indian independence movement arrived in New York: Jagjit Singh, a Sikh from Punjab. British intelligence reports documented that Singh had taken part in Mahatma Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement but, disillusioned by its abrupt cancellation in 1922, had left India. He eventually opened an Indian clothing and textile business on Fifth Avenue. In the art-deco whirl of Manhattan, “J.J.,” as his American friends called him, became the prototypical successful immigrant. His business boomed. A profile in the New York Post described a man who listened to swing music, enjoyed dancing at nightclubs, and had given up Punjabi fare for steaks.

Like Freeman, Singh forged diverse links. He brought a slice of America into the India League: Its membership roster included Detroit labor leaders, Sikh farmers in California, African American activists in Harlem, Chinese immigrants, and a sprinkling of lawmakers. Two of his closest confidants were Sidney Hertzberg, a Jewish socialist, and John Haynes Holmes, a Unitarian minister. Together, Singh and his colleagues dressed up Indian nationalism in red, white, and blue. Urging Americans to support freedom for India, they compared Gandhi to George Washington and printed the Declaration of Independence and its Indian counterpart, issued in 1930, side by side in pamphlets, dinner and event programs, and in the India League’s newsletter. “Indians believe in the teachings of Lincoln and Washington,” Singh’s voice boomed over the radio in 1942. “Indians want to be given the chance to fight and to die for freedom and democracy.”

Over time, efforts by Indian nationalists to win over Washington, D.C., began to have an impact. In 1944, a Washington Post columnist, Drew Pearson, made a scandalous revelation that rocked the Anglo-American alliance: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s top diplomat in New Delhi, William Phillips, had confidentially urged the White House to encourage India’s independence. A clear British promise of freedom for India, Phillips argued, would actually help the war effort. Several India League associates had a hand in the leak. Singh deftly used Phillips’s revelation to drum up further American support for India’s independence.

Along with his work to promote the Indian independence movement, Singh helped Indian immigrants become legally American, pushing to undo the Supreme Court’s 1923 decision that Indians could not become naturalized citizens. Singh partnered with two representatives, Clare Boothe Luce and Emanuel Celler, to draft a bill and then roped in figures as varied as Albert Einstein and W. E. B. Du Bois as supporters. He claimed to have contacted “every newspaper and magazine in the United States” for endorsements. It worked. In July 1946, President Harry Truman approved the Luce-Celler Act, which allowed limited immigration from India (as well as the Philippines), helping pave the way for the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. Singh was invited to the White House to observe Truman sign it into law.

Read: The battle that changed Kamala Harris

Although Singh never took up U.S. citizenship himself, he nevertheless became quintessentially American. His friends and colleagues represented a patchwork of American society. Some of these friends helped Singh finally settle down. In 1951, Hertzberg told Holmes that their mutual friend fancied the daughter of an Indian diplomat and was keen for Holmes to perform their wedding. Thus, with the help of a Jewish socialist, a Christian Unitarian married a Sikh man to a Hindu woman. It is hard to imagine a more American story.

Singh retained a prized possession from his campaign to win Indians the right to naturalize. After the signing ceremony for the Luce-Celler Act, Truman gave Singh the pen with which he affixed his signature, and Singh passed that memento down to his descendents. Today, it is held by his granddaughter, who is herself a prominent member of the Indian American political community—Kamala Harris’s press secretary, Sabrina Singh. In January, she might be able to bring it back to the White House.