Legal-Case-of-the-Tamil-Genocide_30-December-2014

The Legal Case of the Tamil Genocide

Full PDF version available here

By UNROW Human Rights Impact Litigation Clinic

The UNROW Human Rights Impact Litigation Clinic, an impact litigation clinic of American University Washington College of Law, has advocated and litigated on behalf of victims of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka for nearly five years. On September 22, 2010, UNROW released a new report calling for the establishment of a new international tribunal to prosecute those most responsible for the crimes committed during the conflict. In December 2010, UNROW submitted evidence of human rights violations committed during the armed conflict to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Sri Lanka, which U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon appointed in 2010. In September 2011, UNROW filed a lawsuit, Devi v. Silva, on behalf of victims of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka against Shavendra Silva, a former military general who commanded the 58th Division of the Sri Lankan army during the war.

The UNROW Human Rights Impact Litigation Clinic, an impact litigation clinic of American University Washington College of Law, has advocated and litigated on behalf of victims of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka for nearly five years. On September 22, 2010, UNROW released a new report calling for the establishment of a new international tribunal to prosecute those most responsible for the crimes committed during the conflict. In December 2010, UNROW submitted evidence of human rights violations committed during the armed conflict to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Sri Lanka, which U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon appointed in 2010. In September 2011, UNROW filed a lawsuit, Devi v. Silva, on behalf of victims of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka against Shavendra Silva, a former military general who commanded the 58th Division of the Sri Lankan army during the war.

Special recognition to Ali A. Beydoun, UNROW Director and Supervisor, and students Diana Damschroder, Amira Mikhail, and Whitney-Ann Mulhauser for their writing and editing of this piece.

Introduction

Sri Lanka has been mired in ethnic conflict since it received independence from Great Britain in 1948. After centuries of colonial rule, under which the Tamil and Sinhalese territories were primarily administered separately, political power was distributed to the Sinhalese upon independence. Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese, the dominant ethnicity on the island, immediately began—and indeed have not stopped—manipulating ethno-religious nationalism for political gain at the expense of the Tamil community, which constitutes approximately eighteen percent of the island’s population.

Sinhala nationalism was mobilized to disenfranchise and discriminate against the Tamil community. As non-violent Tamil protests were met with state violence and increasing brutality, an armed struggle for a separate Tamil state of Tamil Eelam began.

Sri Lanka’s bloody armed conflict ended over five years ago, killing tens of thousands of Tamil civilian men, women, and children. During the conflict, the international community expressed serious concerns regarding the “fate of civilians caught up in the conflict zone during the final stages of the war, the confinement of some 250,000 Tamil refugees to camps for months afterwards, and allegations that the government had ordered the execution of captured or surrendering rebels.”[1]

Despite the war’s end, however, there has been no accountability or justice for the deaths of innocent Tamils. This article will analyze the Sri Lankan government’s violations of international law relating to the crime of genocide, drawing primarily from U.N. reports and other public materials. The article begins by examining the legal definition of genocide and jurisprudence applying and interpreting the definition of genocidal intent. The article then provides a comparative analysis of Srebrenica, an internationally-recognized genocide, with the crisis in Sri Lanka. The article offers an overview of the evidence demonstrating the Sri Lankan government’s genocidal intent against Tamils, and establishes the need for an international investigation into Sri Lanka’s genocide.

Legal Definition of Genocide and Jurisprudence Interpreting Genocidal Intent

During a campaign to distinguish genocide from other international crimes, international scholar Raphael Lemkin described genocide as a “coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”[2] In part, as a result of his efforts, the U.N. General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide (Genocide Convention) in 1948.[3] The Genocide Convention, however, sets forth a relatively ambiguous and restrictive definition of genocide—restrictive in that to determine whether genocide has occurred, a body with jurisdiction over the alleged crimes must conclude that the acts were carried out against persons of a particular group and targeted based on such membership, the acts fall under at least one of the five enumerated acts, and the perpetrators committed the crimes with the specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the entire group. Sri Lanka acceded to the Genocide Convention in 1950.

Article II of the Genocide Convention provides the following definition of genocide:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.[4]

Under Article II, the group must intend to commit the specific “acts”—e.g., killing—as well as the group must possess the requisite genocidal intent, meaning an “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, . . . [the protected] group, as such.”

When determining whether a group has committed genocide, genocidal intent is an exceedingly difficult evidentiary hurdle. This element is often referred to as dolus specialis or specific intent.[5] The International Criminal Court’s (ICC) Elements of Crimes states that the “[e]xistence of intent and knowledge can be inferred from relevant facts and circumstances.”[6] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has held that genocidal intent “may, in the absence of direct explicit evidence, be inferred from” circumstantial evidence.[7] When proving genocidal intent based on an inference, “that inference must be the only reasonable inference available on the evidence.”[8] Noting that genocidal intent will usually be inferred,[9]and therefore will, in most cases, “be proved by circumstantial evidence,”[10] the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) further elaborated that:

the specific intent of genocide may be inferred from certain facts or indicia, including but not limited to (a) the general context of the perpetration of other culpable acts systematically directed against that same group, whether these acts were committed by the same offender or by others, (b) the scale of atrocities committed, (c) their general nature, (d) their execution in a region or a country, (e) the fact that the victims were deliberately and systematically chosen on account of their membership of a particular group, (f) the exclusion, in this regard, of members of other groups, (g) the political doctrine which gave rise to the acts referred to, (h) the repetition of destructive and discriminatory acts and (i) the perpetration of acts which violate the very foundation of the group or considered as such by their perpetrators.[11]

Persecution has not historically been clearly defined under international instruments until the Rome Statute of the ICC. ICTY jurisprudence clarified that the crime against humanity of persecution “consists of an act or omission, which (1) discriminates in fact and which denies or infringes upon fundamental rights as provided in international customary or treaty law and (2) was carried out deliberately with the intention to discriminate on political, racial or religious grounds.”[12] The Rome Statute defines persecution as the “intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of the identity of the group or collectivity.”[13] International criminal law scholar M. Cherif Bassiouni provided the following composite definition of persecution:

State policy leading to the infliction upon an individual of harassment, torment, oppression, or discriminatory measures, designed to or likely to produce physical or mental suffering or economic harm, because of the victim’s beliefs, views, or membership in a given identifiable group (religious, social, ethnic, linguistic, etc.), or simply because the perpetrator sought to single out a given category of victims for reasons peculiar to the perpetrator.[14]

For persecution to amount to a crime against humanity, it must be “part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population.”[15]

Although persecution is typically contrasted with genocide due to the heightened mens rea burden for genocide, international tribunals have concluded that the crime against humanity of persecution, when committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, an ethnic group, may constitute genocide. The ICTY has noted that “[f]rom the viewpoint of mens rea, genocide is an extreme and most inhuman form of persecution. When persecution escalates to the extreme form of willful and deliberate acts designed to destroy a group or part of a group, it can be held that such persecution amounts to genocide.”[16]

In addition to the following analysis comparing the genocide committed in Srebrenica to Sri Lanka, there is also support to conclude that an extreme and inhuman form of persecution against the Sri Lankan Tamils occurred, amounting to genocide. A U.N. Panel of Experts appointed by Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon found evidence that the Sri Lankan government’s “campaign constituted persecution of the population of the Vanni.” Further, the Panel concluded that there was sufficient evidence to “support a finding of the crime against humanity of persecution insofar as the other acts listed here appear to have been committed on racial or political grounds against the Tamil population of the Vanni, which was perceived by the Government as supporting the LTTE.”[17] As demonstrated below, the Sri Lankan government committed its destructive acts with the intent to destroy the Vanni Tamils as a group and therefore the government’s persecution of the group constitutes genocide.

Inferring Genocidal Intent in Srebrenica and Sri Lanka

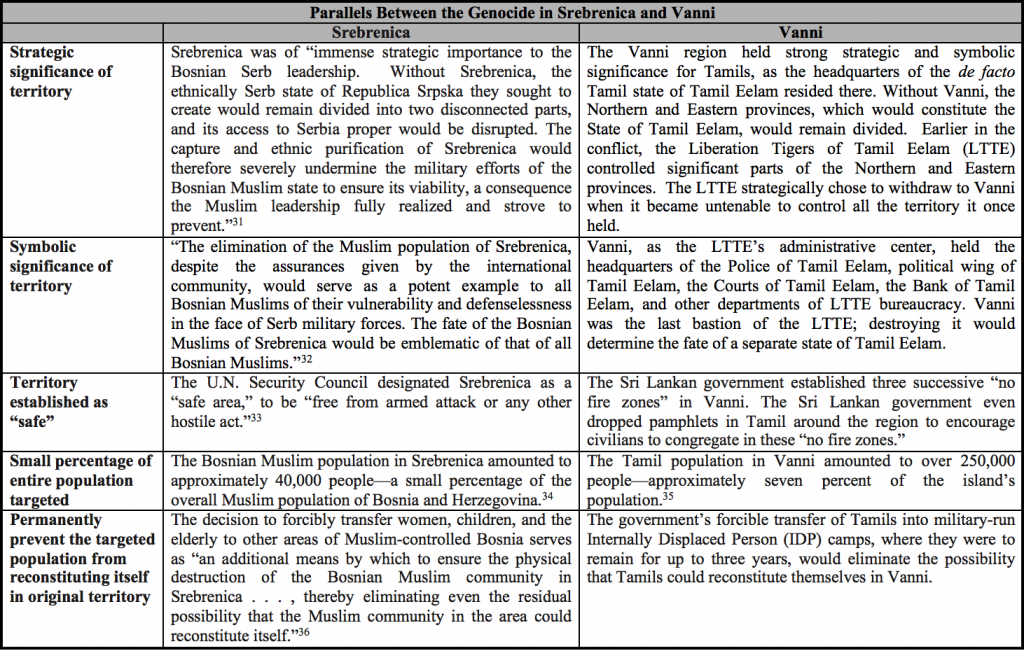

Several parallels can be drawn between the situation in Sri Lanka and other situations where international courts inferred genocide. This section analyzes the case study of Srebrenica to demonstrate that the Sri Lankan government’s persecution of the Tamils rose to the extreme level of willful and deliberate acts designed to destroy the Vanni Tamils, and thus constitutes genocide.

Srebrenica Genocide

In 1993, Srebrenica, a town in Bosnia and Herzegovina, was declared a United Nations safe area, specifically designed to protect civilians from the Bosnian war. However, in 1995, between 7,000 and 8,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) men were systematically killed in this area.[18] Further, Bosniak women, children, and elderly people were forcibly removed from the enclave and transferred to other areas of Muslim-controlled Bosnia.

Only a year after the devastating events of Srebrenica, the ICTY concluded that the perpetrators intended to destroy the Bosniaks in the area. The ICTY found Radislav Krstić, a General-Major in the Bosnian Serb Army (VRS) and Commander of the Drina Corps, guilty of aiding and abetting genocide and the crime against humanity of persecution, among other crimes.[19] The ICTY held that “[t]he intent requirement of genocide under Article 4 of the [ICTY] Statute is therefore satisfied where evidence shows that the alleged perpetrator intended to destroy at least a substantial part of the protected group.”[20] Further, the ICTY noted that “[i]f a specific part of the group is emblematic of the overall group, or is essential to its survival, that may support a finding that the part qualifies as substantial within the meaning of Article 4.”[21]

The Trial Chamber also concluded that certain acts, which are not physically destructive of a life—e.g., forcible transfer to other areas—do not disrupt a finding that the perpetrator possessed the requisite intent to destroy the protected group. The Appeals Chamber agreed with the Trial Chamber that the perpetrators “knew that their activities would inevitably result in the physical disappearance of the Bosnian Muslim population at Srebrenica.”[22] Although forcible transfer “does not constitute in and of itself a genocidal act,” the Trial Chamber may rely on the act as “evidence of the intentions” of the perpetrators. “The genocidal intent may be inferred, among other facts, from evidence of ‘other culpable acts systematically directed against the same group.’”[23]

The Sri Lankan government’s deliberate and willful acts against Tamils are analogous to those committed in Srebrenica. The Sri Lankan government “deliberately used greatly reduced estimates [of the civilian population size], as part of a strategy to limit the supplies going into the Vanni, thereby putting ever-greater pressure on the civilian population.”[24] The Sri Lankan government claimed that 70,000 Tamils were trapped in the conflict zone, an area the size of New York City’s Central Park, while the Red Cross estimated 250,000 people remained in the area.[25] The government intentionally understated the population size in order to hide the total deaths that occurred and to starve the remaining population into submission. During the government’s 2008-2009 military offensive in the Vanni region, the Sri Lankan forces indiscriminately shelled, bombed, and fired guns in the No Fire Zone, killing up to 70,000 Tamil civilians in the final months of the war.[26] As Tamils fled the war zone in early 2009, they were detained in IDP camps that Human Rights Watch said were little better than prisons.[27] In February 2009, the Sri Lankan government released its plan to keep Tamil refugees in five IDP camps for up to three years.[28] The government wanted to construct 39,000 semi-permanent homes, as well as post offices and banks, in these “welfare villages” where refugees were forcibly detained.[29] Like the Bosnian Serb forces’ plan to physically disappear the Bosnian Muslims from Srebrenica, this plan would similarly physically extinguish the Tamils from ever reconstituting their communities in Vanni.

The following chart further outlines the similarities between the two conflicts with respect to proving the elements of the international crime of genocide.

Sri Lanka’s Genocide

Sri Lankan government officials’ statements and actions provide sufficient evidence to show that there are reasonable grounds to believe that government officials acted with the specific intent to destroy the Tamils in Vanni. This evidence has been outlined below.

Government Strategy to Deny and Conceal the Crimes Committed Against Tamils

Evidence has emerged that the Sri Lankan government is attempting to conceal the crimes committed in the Vanni, with Army personnel “deliberately and systematically” seeking to exhume and destroy mass graves.[36]The Public Interest Advocacy Center (PIAC), an Australian-based human rights group, issued an in-depth report regarding crimes allegedly committed by the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE during the war. PIAC obtained eyewitness information regarding the “systematic destruction of civilian mass burial sites in the post-conflict period.”[37] In the report, PIAC reports that:

According to this witness, these burial sites contained human remains from hundreds, and in some instances, thousands of men, women and children who died during the conflict. The precise location of these, and other, burial sites, has been provided to ICEP. This witness has alleged that scores of civilian mass burial sites were systematically destroyed after the conflict. According to this witness, the SFs [Security Forces], and specifically members of the Sri Lankan Police and Sri Lankan Army, are directly implicated in this conduct. This witness believes that senior SFs officials knew that graves were being identified for the purpose of exhumation, and permanent destruction, over a period of more than a year.[38]

This account corroborates a Sri Lankan soldier’s memory of the government bulldozing mass graves.[39] The former soldier reported to Channel 4, a British news outlet, that:

Massive numbers of children, women and men were killed in the final stages of the war. When I say massive, in Puthumathalan alone, over 1500 civilians were killed. But they couldn’t bury all of them. What they did was, they bought a bulldozer, they spread the dead bodies out and put sand on top of them, making it look like a bund. . . . They wanted to clear them [the dead bodies] that’s why they brought that big vehicle. All they could do was just put sand on them. In some areas you couldn’t go because there was such a terrible smell of decomposing bodies. They were just innocent Tamil civilians and did not belong to either warring party.[40]

Additionally, the Sri Lankan government waited nearly two years to admit that any civilian casualties occurred during the final months of the war. Prior to this admission, the government repeatedly alleged that there were no civilian casualties during the war.[41]

Government Officials’ Statements Reflect Genocidal Intent

The following official statements made by high-ranking Sri Lankan officials provide a strong basis for inferring genocidal intent. They depict the anti-Tamil hostility underpinning Sinhala Buddhist chauvinism, which has long been a hallmark feature of Sri Lanka’s ethno-nationalist politics. The government’s construct of Sri Lanka is based on the primacy of the Sinhala identity, which fundamentally excludes Tamils. The extermination of Tamils— particularly Vanni Tamils, who were considered the most ardent Tamil nationalists, and therefore most resistant to the Sinhalization of the Sri Lankan identity—facilitated the realization of the government’s ideal Sri Lankan state.

President Rajapaksa’s following statement captures the exclusionary nature of the Sri Lankan identity. The Tamil identity is no longer recognized—it has been subsumed into the Sinhala “Sri Lankan” identity.

We have removed the word minorities from our vocabulary three years ago. No longer are the Tamils, Muslims, Burghers, Malays and any others minorities. There are only two peoples in this country. One is the people that love this country. The other comprises the small groups that have no love for the land of their birth. Those who do not love the country are now a lesser group.

– President Mahinda Rajapaksa (2005–present) during the ceremonial opening of the Sri Lankan Parliament on May 19, 2009, cited in The Sunday Leader, May 24, 2009.

Defense Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapaksa’s following statement reflects his belief that all persons under attack by the Sri Lankan military were legitimate targets. He reveals his view that every individual who stayed in LTTE-controlled territory was an LTTE sympathizer, and was therefore no longer an “independent observer” or a civilian. His statement further shows that ideological support for the LTTE alone was sufficient cause for death.

There are no independent observers, only LTTE sympathizers. Radio announcements were made and movement of civilians started a month and a half ago.

– Defense Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (2005–present) in an interview to IBN on February 3, 2009

General Sarath Fonseka’s following statement demonstrates the entitlement Sinhalese feel over the island, and the false benevolence with which the Sinhalese will allow Tamils to live there.

I strongly believe that this country belongs to the Sinhalese but there are minority communities and we treat them like our people. . . . We being the majority of the country, 75%, we will never give in and we have the right to protect this country. . . . They can live in this country with us. But they must not try to, under the pretext of being a minority, demand undue things.

– General Sarath Fonseka, the Commander of the Sri Lanka Army (December 2005–July 2009) cited in theNational Post, September 23, 2008

There are also several historical statements from key Sri Lankan leaders that evince an intent to destroy the Tamil people. Former President J.R. Jayawardane’s following statement reflects the zero-sum mentality of successive Sri Lankan governments with respect to the Tamil people. He is conveying the sentiment that the Sinhalese are happier and more secure on an island without Tamils. He is also alluding to the government’s oft-utilized strategy of depriving Tamils of food and humanitarian aid, seen in the embargos against the North-East throughout the decades of conflict, and, of course, during the 2008-2009 offensive.

I am not worried about the opinion of the Tamil people . . . now we cannot think of them, not about their lives or their opinion . . . the more you put pressure in the north, the happier the Sinhala people will be here . . . . Really if I starve the Tamils out, the Sinhala people will be happy.

– President J.R. Jayawardane (1977–1988), cited in Daily Telegraph, July 11, 1983.

Government-sponsored colonization schemes have worked to alter traditional demographics on the island. Tamils habiting the contiguous Northern and Eastern provinces presented the gravest threat to the unity of the Sri Lankan state, so within years of receiving independence, the Sinhala government attempted to suppress this threat by financing land grabs in the East. Since independence, the population of Tamils in the Eastern Province decreased by ten percent while the Sinhalese population increased by fifteen percent.[42]

Today you are brought here and given a plot of land. You have been uprooted from your village. You are like a piece of driftwood in the ocean; but remember that one day the whole country will look up to you. The final battle for the Sinhala people will be fought on the plains of Padaviya. You are men and women who will carry this island’s destiny on your shoulders. Those who are attempting to divide this country will have to reckon with you. The country may forget you for a few years, but one day very soon they will look up to you as the last bastion of the Sinhala.

– The first Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake (1947–1952), addressing Sinhala colonists being settled in the traditionally Tamil Eastern Province in the early days of Ceylon’s independence.[43] Padaviya is in the district of Anurathapuram, located on the border between the traditionally Tamil region and the Sinhala region in the south of Sri Lanka.

These historical statements provide the contextual background to the atrocities of 2009, and help explain the willful silence and complicity of the Sinhala public in whitewashing these crimes after 2009.

Nature and Extent of the Violence Committed by Government Forces Against Tamils

According to a U.N. Internal Review Report, up to 70,000 Tamil civilians were killed in the final months of the war.[44] Mass graves continue to be unearthed throughout North-East Sri Lanka. In January, a grave with an estimated thirty-one bodies, many of whom were women and children, was found in a Tamil area near the location of the final stages of the war.[45] These bodies are presumably among the thousands of civilians executed and covered up by Sri Lankan security forces. The nature and extent of Sri Lanka’s violence against Tamils will be explored in greater depth in Section II below.

Control of the State

According to recent reports, the Rajapaksa family has a total of twenty-nine family and extended family members filling high-level civil service and industry positions, and the family controls between forty-five and seventy percent of the national budget.[46] President Rajapaksa’s brother, Gotabaya, was appointed Defense Secretary in 2005 upon the President’s election. He held office throughout and beyond the final months of Sri Lanka’s armed conflict. In 2011, two Sri Lankan Army soldiers testified that Gotabaya Rajapaksa crafted the strategy for the final assault on the LTTE that resulted in thousands of Tamil civilian deaths.[47] The testimony, coupled with circumstantial evidence, indicate high-level control of military resources as well as decisions that knowingly led to Tamil civilian casualties. Another brother, Basil Rajapaksa, is both Minister for Economic Development and the head of the “President’s Task Force,” a body appointed to rebuild the North, and coordinate the security forces in rehabilitation, resettlement, and development.[48] These three Rajapaksa brothers control five of the largest government ministries. Chamal Rajapaksa, another brother, is the speaker of the Sri Lankan parliament. Additionally, Upul Dissanayaka—a member of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s extended family—manages one of the largest news publishers, The Associated Newspapers of Ceylon.[49]

Sri Lankan Government’s Campaign Against Tamils Constitutes Genocide

Extensive evidence is available that satisfies four of the five enumerated genocidal acts in the Genocide Convention: (1) killing members of the group; (2) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (3) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; and (4) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group. This section is not exhaustive of all the evidence available that supports the legal conclusions set forth herein.

Killing Members of the Group

According to the U.N. Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lankan government:

[S]helled on a large scale in three consecutive No Fire Zones, where it had encouraged the civilian population to concentrate, even after indicating that it would cease the use of heavy weapons. It shelled the United Nations hub, food distribution lines and near the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) ships that were coming to pick up the wounded and their relatives from the beaches. It shelled in spite of its knowledge of the impact, provided by its own intelligence systems and through notification by the United Nations, the ICRC and others. Most civilian casualties in the final phases of the war were caused by Government shelling.[50]

At the end of January 2009, government forces were killing approximately thirty-three Tamil people each day, with these casualties increasing to 116 people per day by April 2009. This toll surged, “with an average of 1,000 civilians killed each day until May 19, 2009.”[51] The U.N. Panel of Experts reported on an elite unit within the Special Task Force (STF) of the police that was directly under the command of Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The Experts found that the unit was implicated in organizing “white van” operations in which individuals were abducted, tortured, and often “disappeared.”[52]

President Mahinda Rajapaksa publicly stated that the Army strategically and intentionally cornered Tamils. According to the President, “[t]hese were not areas demarcated by the U.N. or somebody else; they were demarcated by our armed forces. The whole thing was planned by our forces to corner them. The Army was advancing from North to South, South to North, on all sides. So I would say they got cornered by our strategies.”[53] Further, Callum Macrae, director of award-winning documentaries about Sri Lanka with UK’s Channel 4, corroborated the President’s statements, finding “evidence that the attacks killing civilians were accurately targeted.”[54] In addition to deliberate shelling of civilians, systematic executions demonstrate intent to kill Tamils.

Callum Macrae also reported that evidence exists “depicting the systematic and cold-blooded execution of bound, naked prisoners—and which also suggests sexual assault of naked female fighters.” At least 200 deceased and mutilated bodies, primarily of Tamil women and young girls, were observed by the employee of an international agency at the mortuary of a government hospital in February and March 2009. As reported to the International Crimes Evidence Project, “many of the bodies of the women were naked and bore physical evidence of rape and sexual mutilation, with knife wounds in the nature of long slashes, bite marks or deep scratches on the breasts, and vaginal mutilation by knives, bottles and sticks . . . . The bodies also typically bore signs of gunshot wounds to the forehead, which appeared to have been inflicted at close range due to the lack of peripheral damage.”[55]

Causing Serious Bodily or Mental Harm to Members of the Group

The U.N. Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka found credible allegations that security forces committed rape and sexual violence against Tamil civilians while screening those leaving areas of conflict and in IDP camps.[56]

Yasmin Sooka, one of the experts who contributed to the Secretary-General’s U.N. report, released her own report in March 2014, concluding that “[a]bduction, arbitrary detention, torture, rape and sexual violence have increased in the post-war period . . . . These widespread and systematic violations by the Sri Lankan security forces occur in a manner that indicates a coordinated, systematic plan approved by the highest levels of government.”[57] The report found “a pattern of targeting Tamils for abduction and arbitrary detention unconnected to a lawful purpose, involving widespread acts of torture and rape.”[58] This report was based on forty sworn statements from witnesses who testified regarding their experiences of abduction, torture, and sexual violence by Sri Lankan security forces between May 2009 and February 2014. The report “paints a chilling picture of the continuation of the conflict against the ethnic Tamil Community with the purpose of sowing terror and destabilising community members who remain in the country.”[59] The report identified “a practice of rape and sexual violence that has become institutionalized and entrenched in the Sri Lankan security forces.”[60] Survivors reported being raped by uniformed male officers from the Sri Lankan military.[61] A witness recounted a disturbing interaction with an officer who told her, “you Tamil, you slave, if we make you pregnant we will make you abort . . . you are Tamil we will rape you like this, this is how you will be treated, even after an abortion you will be raped again.”[62]

A Human Rights Watch report released in February 2013 also documented seventy-five cases of politically motivated sexual assaults of primarily Tamil detainees. Human Rights Watch found “disturbing patterns, strongly suggesting that [sexual violence] was a widespread and systematic practice,” and concluded that rape was a key element of more wide-ranging torture “intended to . . . instill terror in individuals and the broader Tamil population.”[63] The report stated that “[s]exual violence, as with other serious abuses committed by Sri Lankan security forces, was committed against a backdrop of deeply entrenched impunity.”[64]

Further, systematic attacks on hospitals during the 2009 military campaign caused serious bodily and mental harm to Tamils. Human Rights Watch documented at least thirty such attacks on permanent and makeshift hospitals in the combat area after December 2008.[65] Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s Defense Secretary, told Sky News that any hospital that was not within the unilaterally declared “no fire zone” set up by the government was a legitimate target.[66]

The destructive campaign has caused permanent mental effects on those who survived. Investigators with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and Sri Lanka Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition conducted a health survey of Jaffna District residents between July and September 2009. They found that the “prevalence of PTSD (13%), anxiety (48.5%), and depression (41.8%) symptoms among currently displaced Jaffna residents is more comparable with post-war Kosovars and Afghans.”[67] As noted by the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal on Sri Lanka, “continuous displacement and endless trauma caused by protracted war had a devastating impact” on mental health among Tamils.[68]Further, the government continues to impose restrictions on psychosocial support services in Tamil areas,[69]which further exacerbates serious mental harm.

Deliberately Inflicting on the Group Conditions of Life Calculated to Bring About its Physical Destruction in Whole or in Part

A military blockade against Tamil areas has been in place since 1990, except for ceasefire periods, which has contributed to the historical impoverishment and isolation of the Tamil community. The blockade has prevented ordinary items such as cement, gasoline, candles, and chocolate from entering Tamil areas. During the certain periods of the ethnic conflict, the military adopted a harsher stance, and blocked all humanitarian aid intended for civilians. The U.N. Panel of Experts Report found that the government deliberately understated the Tamil population size “as part of a strategy to limit the supplies going into the Vanni.”[70] The Panel of Experts Report continued, noting that “[a] senior Government official subsequently admitted that the estimates were reduced to this end. The low numbers also indicate that the Government conflated civilians with LTTE in the final stages of the war.”[71] According to the International Crimes Evidence Project, the government’s refusal of “adequate food and medical supplies into the Vanni despite being aware of the devastating effect it would have on civilians, … could have amounted to inhumane acts or persecution, or both.”[72] Such intentional starvation demonstrates the government’s deliberate infliction of deadly conditions calculated to bring about the physical destruction of Tamils.

Callum Macrae also found evidence of “the deliberate denial of adequate humanitarian supplies of food and medicine to civilians trapped in those grotesquely misnamed No Fire Zones. To justify this policy, the government systematically underestimated the number of civilians trapped in the zones. At the end of April 2009, for example, President Rajapaksa told CNN that ‘there are only about 5,000 . . . even 10,000’ civilians left in the zones.” According to accurate U.N. figures, however, more than 125,000 civilians were stuck in these zones. President Rajapaksa endorsed the inaccurate figures as a means to “justify what almost certainly constitutes a war crime—a crime that left thousands of civilians catastrophically short of food and water—and allowed hundreds to die unnecessarily in makeshift hospitals because of desperate shortages of supplies including blood and anesthetics.”[73] Amnesty International’s Asia director, Sam Zafiri, reportedly stated that the Sri Lankan government’s policy of obstructing aid was deliberate and illegal, noting that “[i]nternational law bans medieval sieges—you can’t subject a population to hunger, famine or plague as a means of military victory.”[74] Today, the Tamil community “shows clear signs of continuing deterioration in terms of health, food and social security.”[75] In the North-East areas, the malnutrition level has reached fifty percent, “corresponding also with the alarming poverty rate measured at [fifty-eight percent]”[76] in those regions.

The systematic expulsion of victims from their homes is another means of inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about the physical destruction of a group, as stated by the International Criminal Tribunals.[77] The Sri Lankan government used this practice extensively against the Tamils, confiscating the Tamils’ private land.[78] In May 2013, 1,474 northern Tamils filed a petition against the government’s confiscation of their land,[79] stating that 6,381 acres were appropriated to build another Army base in Jaffna. The majority of these individuals were refused permission to return to their lands and forced to remain in the “welfare villages,” which enabled the government to claim that the owners of these lands are “unidentifiable.”[80]

Even five years after the end of the war, Sri Lanka announced a defense budget of $1.95 billion for 2014 (twelve percent of the overall 2014 state budget).[81] The Sri Lankan military’s current reach includes police powers throughout the country, with search and detention authority. In Tamil-speaking areas, the Sri Lankan military is “increasing its economic role, controlling land and seemingly establishing itself as a permanent, occupying presence.”[82] The heavy militarization of the North-East areas has led to the drastic increase in Sinhalese settlers, land grabs, construction of Buddhist temples, conversion of village names and street signs from Tamil to Sinhalese, and unrestricted Sinhalese enterprise, all of which threaten to permanently alter the local demography and exacerbate ethnic tensions, as noted by the International Crisis Group.[83] Evidence related to the “escalation of militarisation, colonisation and forcible imposition of Sinhala Buddhist culture in the Eelam Tamil areas” contributed to a finding of genocide by the Peoples’ Tribunal on Sri Lanka.[84]

Imposing Measures Intended to Prevent Births within the Group

Doctors aligned with the Sri Lankan government performed unconsented abortions on Tamil women. In May 2007, a confidential cable from the United States Embassy in Colombo stated, “Father Bernard also told us of an EPDP [Eelam People’s Democratic Party, a pro-government paramilitary organization] medical doctor named Dr. Sinnathambi, who performs forced abortions, often under the guise of a regular check-up, on Tamil women suspected of being aligned with the LTTE.”[85]

Further, in August 2013, government health workers forced mothers to accept surgically implanted birth control in the Tamil villages of Veravil, Keranchi, and Valaipaddu in Kilinochchi in the Northern Province.[86]When the women objected, the nurses said that if they did not agree to the contraceptive, they could be denied treatment at the hospital in the future.[87] A Ministry of Health Department report from the Northern Province in 2012 found an unjustifiably higher rate of birth control implants—thirty times higher—in Tamil women in Mullaitivu, compared to the much more densely populated Jaffna.[88] According to the Home for Human Rights (HHR), an organization of lawyers devoted to protecting the fundamental rights of those living in Sri Lanka, more than eighty percent of Tamil women in central Sri Lanka were offered a lump sum payment in return for their ability to reproduce. After receiving this payment—typically 500 rupees—women underwent surgical sterilization. This amount of money is significant, especially for these who are predominantly plantation workers. The population of this Tamil group has dropped annually since 1996 by five percent, whereas the population of the country overall has grown by fourteen percent.[89] In contrast, police and Army officers have been encouraged to have a third child through payment of 100,000 rupees from the government. The police and Army are overwhelmingly Sinhalese, and thus those taking advantage of this offer are Sinhalese.[90] “This systematic pattern of authority-sanctioned coerced sterilizations may amount to an intentional destruction . . . of the Tamil estate population,” as noted by the Home for Human Rights.[91]

Conclusion

The Preamble to the Rome Statute provides that one of the core goals of the Statute is to end impunity for the perpetrators of the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole, which “must not go unpunished.”[92] The post-war situation in Sri Lanka cannot be called ‘post-conflict,’ as it reflects a deteriorating human rights situation with rampant government abuses. The very purpose of the Genocide Convention and later efforts after the Rwandan Genocide, are under threat so long as the international community fails to hold the perpetrators accountable for the bloody armed conflict in Sri Lanka. Impunity will inevitably breed further injustice, which has been demonstrated by recent assaults to the remaining Tamil population.

Members of the international community have acknowledged that genocide took place in Sri Lanka and several have called for an independent investigation. Government officials from Australia,[93] Canada,[94]the United Kingdom,[95] and India,[96] as well as Tamil MPs in Sri Lanka[97] have requested an investigation into Sri Lanka’s genocide. International human rights advocates[98] and organizations[99] have similarly called for such an investigation.

The obligation to prevent and punish genocide under the Genocide Convention is not a matter of political choice or calculation, but one of binding customary international law. The Office of the High Commission on Human Rights’ Investigation on Sri Lanka (OSIL) should investigate and report on the charge of genocide in its submission to the UN Human Rights Council in March 2015. The UN Security Council should refer the situation in Sri Lanka to the International Criminal Court for prosecutions based on war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Alternatively or concurrently, domestic courts in countries that may exercise universal jurisdiction over the alleged events and perpetrators, including but not limited to the United States, should prosecute these crimes. Top Sri Lankan officials, starting with President Mahinda Rajapaksa and Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, must be brought to justice.

Endnotes

[1] Sri Lanka Profile, B.B.C. News (Sept. 18, 2014), http://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-11999611.

[2] Raphael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe 79 (2005).

[3] The Genocide Convention entered into force in 1951.

[4] Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, art. II, Dec. 9, 1948, 78 U.N.T.S. 1021, http://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%2078/volume-78-I-1021-English.pdf.

[5] Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro), 2007 I.C.J. 43, ¶ 187 (Feb. 26, 2007), http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/91/13685.pdf.

[6] Int’l Criminal Court, Elements of Crimes (2011), http://www.icc-cpi.int/nr/rdonlyres/336923d8-a6ad-40ec-ad7b-45bf9de73d56/0/elementsofcrimeseng.pdf.

[7] Prosecutor v. Jelisic, Case No. IT-95-10-A, ¶ 47 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, July 5, 2001), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/jelisic/acjug/en/jel-aj010705.pdf.

[8] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-A, ¶ 41 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Apr. 19, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/acjug/en/krs-aj040419e.pdf.

[9] Prosecutor v. Gacumbitsi, Case No. ICTR-2001-64-A, ¶ 40 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Rwanda, Appeals Chamber, July 7, 2006), http://www.unictr.org/sites/unictr.org/files/case-documents/ictr-01-64/appeals-chamber-judgements/en/060707.pdf.

[10] Prosecutor v. Nahimana, Barayagwiza, and Ngeze, Case No. ICTR-99-52-A, ¶ 524 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Rwanda, Appeals Chamber, Nov. 28, 2007), http://www.refworld.org/docid/48b5271d2.html.

[11] Prosecutor v. Seromba, Case No. ICTR-2001-66-A, ¶ 176 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Rwanda, Appeals Chamber, Mar. 12, 2008), http://www.refworld.org/docid/48b690172.html; see also Prosecutor v. Jelisic, Case No. IT-95-10-A, ¶ 47 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, July 5, 2001) (holding that “proof of specific intent . . . may, in the absence of direct explicit evidence, be inferred from a number of facts and circumstances, such as the general context, the perpetration of other culpable acts systematically directed against the same group, the scale of atrocities committed, the systematic targeting of victims on account of their membership of a particular group, or the repetition of destructive and discriminatory acts”).

[12] M. Cherif Bassiouni, Crimes against Humanity: Historical Evolution and Contemporary Application 397-98 (2011).

[13] Rome Statute on the International Criminal Court, art. 7(2)(g), July 1, 2002, 2187 U.N.T.S. 38544.

[14] M. Cherif Bassiouni, Crimes against Humanity: Historical Evolution and Contemporary Application 396 (2011).

[15] Rome Statute on the International Criminal Court, art. 7(1)(h), July 1, 2002, 2187 U.N.T.S. 38544.

[16] Prosecutor v. Kupreškić, Case No. IT-95-16-T, ¶ 636 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Trial Chamber, Jan. 14, 2000), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/kupreskic/tjug/en/kup-tj000114e.pdf; see also Prosecutor v. Brdjanin, Case No. IT-99-36-T, ¶ 699 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Trial Chamber, Sept. 1, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/brdanin/tjug/en/brd-tj040901e.pdf.

[17] U.N. Secretary-General, Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, ii, 69 (Mar. 30, 2011) [hereinafter U.N. Panel of Experts Report], available athttp://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4db7b23e2.html.

[18] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-A, ¶ 2 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Apr. 19, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/acjug/en/krs-aj040419e.pdf.

[19] Id. ¶ 3. The ICTY appeals chamber overturned his genocide conviction but affirmed his aiding and abetting genocide conviction. ICTY, Case Information Sheet: Srevrenica-Drina Corps (IT-98-33) Radislav Krstic 9, available at http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/cis/en/cis_krstic.pdf.

[20] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-A, ¶ 12 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Apr. 19, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/acjug/en/krs-aj040419e.pdf.

[21] Id.

[22] Id. ¶ 47.

[23] Id. ¶ 33.

[24] UN Panel of Experts Report, supra note 18, at 39.

[25] Ravi Nessman, Sri Lanka Plans to House War Refugees for 3 Years, Fox News, Feb. 11, 2009, http://www.foxnews.com/printer_friendly_wires/2009Feb11/0,4675,ASSriLankaCamps,00.html.

[26] U.N. Secretary-General, Report of the U.N. Secretary-General’s Internal Review Panel on United Nations Action in Sri Lanka (Nov. 2012) [hereinafter U.N. Internal Review Panel Report], http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Sri_Lanka/The_Internal_Review_Panel_report_on_Sri_Lanka.pdf

[27] Ravi Nessman, Sri Lanka Plans to House War Refugees for 3 Years, Fox News, Feb. 11, 2009, http://www.foxnews.com/printer_friendly_wires/2009Feb11/0,4675,ASSriLankaCamps,00.html.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-A, ¶ 15 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Apr. 19, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/acjug/en/krs-aj040419e.pdf.

[31] Id. ¶ 16.

[32] United Nations Security Council Resolution 819, UN Doc. S/RES/819 (Apr. 16, 1993).

[33] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-A, ¶ 15 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Apr. 19, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/acjug/en/krs-aj040419e.pdf.

[34] Ravi Nessman, Sri Lanka Plans to House War Refugees for 3 Years, Fox News, Feb. 11, 2009, http://www.foxnews.com/printer_friendly_wires/2009Feb11/0,4675,ASSriLankaCamps,00.html.

[35] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-A, ¶ 31 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Apr. 19, 2004), http://www.icty.org/x/cases/krstic/acjug/en/krs-aj040419e.pdf.

[36] Helen Davidson, Sri Lankan Security Forces Destroyed Evidence of War Crimes, Report Claims, The Guardian, Feb. 5, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/05/sri-lankan-forces-committed-flagrant-and-reckless-violations-of-human-rights-report-claims (reporting on evidence “that suggests the Sri Lankan government may have deliberately and systematically sought to exhume bodies from mass graves in a bid to hide evidence of the mass killings”).

[37] Public Interest Advocacy Center, Int’l Crimes Evidence Project, Island of Impunity? Investigation into international crimes in the final stages of the Sri Lankan Civil War 190 (2014) [hereinafter Public Interest Advocacy Center: Int’l Crimes Evidence Project], http://www.piac.asn.au/sites/default/files/publications/extras/island_of_impunity.pdf.

[38] Id. (emphasis added).

[39] The Sri Lankan Soldiers ‘Whose Hearts Turned To Stone’, Channel 4 News, July 27, 2011, http://www.channel4

.com/news/the-sri-lankan-soldiers-whose-hearts-turned-to-stone.

[40] Id.

[41] President Mahinda Rajapaksa, Keynote Address to the Honorary Consuls of Sri Lanka Abroad (Jan. 19, 2009), (transcript available at http://www.mea.gov.lk/index.php/en/media/statements/1561-keynote-address-by-president-mahinda-rajapaksa-to-the-honorary-consuls-of-sri-lanka-abroad-).

[42] Pre-independence, the Eastern province was 49% Tamil, 39% Muslim, and 8% Sinhala. Today, it is 40% Tamil, 37% Muslim and 23% Sinhala. Robert N. Kearney, Territorial Elements of Tamil Separatism in Sri Lanka, 60 Pac. Aff. 561 (1987-88).

[43] H.M. Gunaratne, For a Sovereign State 201 (1988).

[44] U.N. Internal Review Panel Report, supra note 27.

[45] Charles Haviland, Sri Lanka Mass Grave Yields More Skeletons, BBC News, Jan. 18, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/

news/world-asia-25782902.

[46] Five Infographics About Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace & Justice (Mar. 20, 2013), http://blog.

srilankacampaign.org/2013/03/five-inographics-about-sri-lanka.html.

[47] Jonathan Miller, Sri Lanka ‘War Crimes’ Soldiers Ordered to ‘Finish the Job’, Channel 4 News, July 27, 2011, http://www.channel4.com/news/sri-lanka-war-crimes-soldiers-ordered-to-finish-the-job.

[48] Resettlement, Development and Security in the Northern Providence: President Appoints Task Force Mandated to Report Within One Year, Ministry of Def. & Urban Dev. Sri Lanka (Dec. 30, 2010, 11:41 PM), http://www.

defence.lk/new.asp?fname=20090514_03.

[49] Five Infographics About Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace & Justice (Mar. 20, 2013), http://blog.

srilankacampaign.org/2013/03/five-inographics-about-sri-lanka.html.

[50] UN Panel of Experts Report, supra note 18, at ii.

[51] Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, Peoples’ Tribunal on Sri Lanka, ¶ 5.1.4.1(a) (2013), available athttp://www.ptsrilanka.org/images/documents/ppt_final_report_web_en.pdf.

[52] UN Panel of Experts Report, supra note 18, at 29.

[53] We Knew They Would Never Lay Down Arms and Start Negotiating, The Hindu, July 7, 2009, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-opinion/we-knew-they-would-never-lay-down-arms-and-start-negotiating/article222566.ece (Mahinda Rajapaksa interview).

[54] Callum Macrae, Sri Lanka: A Child is Summarily Executed, The Independent, Mar. 11, 2012, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/sri-lanka-a-child-is-summarily-executed-7555062.html.

[55] Public Interest Advocacy Center: Int’l Crimes Evidence Project, supra note 38, at 157.

[56] UN Panel of Experts Report, supra note 18, ¶¶ 148, 152-53, 228.

[57] Yasmin Sooka, An Unfinished War: Torture and Sexual Violence in Sri Lanka 2009–2014, The Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales and The International Truth & Justice Project, Sri Lanka 6 (2014), available at http://www.barhumanrights.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/news/an_

unfinihsed_war._torture_and_sexual_violence_in_sri_lanka_2009-2014_0.pdf.

[58] Id. at 53.

[59] Id. at 62.

[60] Id. at 37.

[61] Id. at 36.

[62] Id. at 38.

[63] Human Rights Watch, We Will Teach You a Lesson: Sexual Violence Against Tamils by Sri Lankan Security Forces 29 (2013), http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/srilanka0213webwcover_0.pdf.

[64] Id. at 18.

[65] Sri Lanka: Repeated Shelling of Hospitals Evidence of War Crimes, Human Rights Watch, May 8, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/news/2009/05/08/sri-lanka-repeated-shelling-hospitals-evidence-war-crimes.

[66] Alex Crawford, Packed Sri Lanka Hospital Shelled, Sky News, Feb. 2, 2009, http://news.sky.com/story/

667068/packed-sri-lanka-hospital-shelled.

[67] Farah Husain et al., Prevalence of War-Related Mental Health Conditions and Association with Displacement Status in Postwar Jaffna District, Sri Lanka, 306 JAMA 522 (2011), available athttp://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/gdder/ierh/publications/srilankastudy2011.pdf.

[68] Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, supra note 52, § 5.1.4.1(b).

[69] High Commissioner for Human Rights, Opening Remarks by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay at a Press Conference During her Mission to Sri Lanka Colombo (Aug. 31, 2013), http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=13673 (stating that “[b]ecause of the legacy of massive trauma, there is a desperate need for counseling and psychosocial support in the North, and I was surprised and disappointed to learn that the authorities have restricted NGO activity in this sector. I hope the Government can relax controls on this type of assistance”).

[70] UN Panel of Experts Report, supra note 18, at 39.

[71] Id.

[72] Public Interest Advocacy Center: Int’l Crimes Evidence Project, supra note 38, § 5.28.

[73] Callum Macrae, Sri Lanka: A Child is Summarily Executed, The Independent, Mar. 11, 2012, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/sri-lanka-a-child-is-summarily-executed-7555062.html.

[74] Id.

[75] Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, supra note 52, § 5.1.5.

[76] Id.

[77] Prosecutor v. Akayesu, Case No. ICTR-96-4-T, ¶ 506 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for Rwanda, Trial Chamber, Sept. 2, 1998); Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, supra note 52, § 5.1.5.

[78] Id.

[79] 1474 Northern Tamils Petition Appeal Court To Help Prevent Grab Of Their Homes By Rajapaksa Regime, Colombo Telegraph, May 15, 2013, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/1474-northern-tamils-petition-appeal-court-to-help-prevent-grab-of-their-homes-by-rajapaksa-regime/.

[80] Id.

[81] Jon Grevatt, Sri Lanka Outlines 2014 Defence Spending, IHS Jane’s 360, Oct. 22, 2013, http://www.janes.com/article/28793/sri-lanka-outlines-2014-defence-spending.

[82] Int’l Crisis Grp., Sri Lanka’s North II: Rebuilding under the Military (2012),http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/south-asia/sri-lanka/220-sri-lankas-north-ii-rebuilding-under-the-military.aspx.

[83] Id.

[84] Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, supra note 52, § 5.1.5.

[85] Cable from Robert Blake, Sri Lanka: GSL Complicity in Paramilitary, Wikileaks (May 18, 2007), http://wikileaks.org/cable/2007/05/07COLOMBO728.html

[86] The Social Architects, Coercive Population Control in Kilinochchi, Groundviews, Sept. 13, 2013, http://groundviews.org/2013/09/13/coercive-population-control-in-kilinochchi/.

[87] Id.

[89] Demographic Engineering by the Government of Sri Lanka: Is this Eugenics?, The Sri Lanka Campaign (Sept. 12, 2011), http://blog.srilankacampaign.org/2011/12/demographic-engineering-by-government.html.

[90] Id.

[91] Id.

[92] Rome Statute on the International Criminal Court, Preamble, July 1, 2002, 2187 U.N.T.S. 38544.

[93] Australian Senator Lee Rhiannon, who was detained in Sri Lanka while on a fact-finding mission, condemned the Australian government for giving “cover to a President and government accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and ongoing human rights abuses.” Australian Senator Remembers Tamils Killed by Systematic Sri Lankan State Brutality, Tamil Guardian, Nov. 26, 2014, http://www.tamilguardian.com/article.asp?articleid=12952.

[94] MP Jim Karygiannis stated that “[i]t takes three parties to create a genocide—the perpetrators, the victims and those who stand by. The international community must stop standing idly by. While the killing has stopped, we must tell the Sri Lankan government to stop the cultural genocide and submit to an international inquiry into the 2009 war.” The Honorable Jim Karygiannis, 30th Anniversary of Black July Statement (July 21, 2013) (transcript available at http://www.karygiannismp.com/article.php3?id_article=2186).

[95] All-Party Parliamentary Group for Tamils (UK)—a group of 69 MPs from all political parties—stated that “APPGT strongly urges the UN to the creation of an International Commission of Investigation into the allegations of War crimes, Crimes against Humanity and the Crime of genocide against the Tamil people in Sri Lanka.” Press Release, The All Parliamentary Group for Tamils, Calling for an International Independent Investigation (Mar. 2013), available at http://britishtamilconservatives.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/THE-ALL-PARTY-PARLIAMENTARY-GROUP-FOR-TAMILS-statement-re-UNHRC-MARCH-13.pdf. MP Andrew Dismore noted that, “[i]n many cases, the killings have been what independent observers would define as genocide, with whole communities killed in a form of ethnic cleansing. With the eyes of the world turned elsewhere, the Sri Lankan government has felt able to get away with this slaughter, despite condemnation from the Dalai Lama and the UN secretary general.” Andrew Dismore, Stop Sri Lanka’s Bloody Civil War, The Guardian, Mar. 4, 2009, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/mar/04/sri-lanka.

[96] MP Yashwant Sinha suggested that investigators “[g]o from mandal to mandal, house to house and tell the people how Sonia Gandhi and Manmohan Singh have been responsible for the genocide in the immediate neighbourhood of north Lanka.” Sva Prasanna Kumar, Tamil Elam is Not Far Away: Yashwant Sinha, Deccan Chronicle, Apr. 4, 2013, http://archives.deccanchronicle.com/130404/news-politics/article/tamil-eelam-not-far-away-yashwant-sinha. Further, the Tamil Nadu state government passed a resolution that urged an impartial, international, and independent probe for alleged war crimes and genocide in Sri Lanka and stated that “[b]ased on this investigation, those found guilty should be tried in the international court of law and punished.” R. Satyanarayana, Jayalalithaa Calls for a Referendum on Separate Eelam, Times of India, Mar. 27, 2013, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Jayalalithaa-calls-for-a-referendum-on-separate-Eelam/articleshow/19239891.cms.

[97] MP Suresh Premachandran, spokesperson of the Tamil National Alliance, stated that “[i]f 7,000 deaths in Kosovo could be described as genocide, why can’t the deaths in Mulliwaikkal be?” P.K. Balachandran, Can’t Brush Aside Genocide in Sri Lanka, Indian MPs Told, The New Indian Express, Apr. 11, 2013, http://www.newindianexpress.com/world/Can%E2%80%99t-brush-aside-genocide-in-Sri-Lanka-Indian-MPs-told/2013/04/11/article1539645.ece#.Uwp_YPkhBv8.

[98] Prominent Human Rights Activist Arundhati Roy stated that “[w]hat happened in the war [in Sri Lanka], cannot be called anything short of a genocide. And perhaps as horrific as what happened there, has been the silence that has followed it.” TamilHumanrights, Sri Lanka Committed Genocide of Tamils: Arundhati Roy, YouTube (June 12, 2011), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LrSfK6Pm-5M.

[99] Population Research Institute noted that “[f]orced contraception and sterilization are nothing short of acts of genocide. Sadly, these are regular occurrences in the island nation of Sri Lanka.” Population Research Inst., Tamil Women Coerced into Contraception by Sri Lankan Authorities, LifeSiteNews, Feb. 3, 2014,http://www.lifesitenews.com/news/tamil-women-coerced-into-contraception-by-sri-lankan-authorities. Further, the organization stated that “[l]ocal health officials are belatedly trying to cover up their crimes. They are coercively and retroactively forcing already sterilized Tamil women to sign affidavits. Such affidavits should not convince anyone that these ‘birth control experiments’ are anything other than genocide. Far from convincing, false affidavits of consent instead add insult to injury by suggesting that the dead women voluntarily submitted themselves to the procedure.” Id.

The Int’l Court of Justice rejected Balkan claims of genocide. The judge said:”Ethnic cleansing does not constitute genocide.”