by Sachi Sri Kantha, January 21, 2014

Part 13 concluded with one of MGR’s logic in movie making; which is,“One can work with those who know everything. One can also work with those who don’t know anything. But, one shouldn’t work with those who know nothing, but pretends to know everything.”

In retrospect, none can find fault with this logic. Not only in movie world, but even among academics, technicians, journalists and critics, we do find half-baked criticism rendered by those who don’t know anything, but pretends to know everything. Thus, it is apt now to tackle the criticism of movie critics on MGR’s modus operandi in movie making. I focus on three such critics, Chidananda Das Gupta, M.S.S. Pandian and Prof. K. Sivathamby. All three conspicuously had ‘Communist-Socialist-Progressive’ interests in their writing. Among these three, Pandian and Sivathamby are Tamil literate, but Das Gupta (being a Bengali native) is not.

Chidananda Das Gupta (1921-2011) was a film critic, who established his name as a co-founder of Calcutta Film Society (in 1947) and the Federation of Film Societies of India (in 1960). He also promoted himself as a Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) scholar. Satyajit Ray is recognised as one of the 20th century auteurs of Indian cinema. Actress and director Aparna Sen (born 1945) was a daughter of Das Gupta.

Das Gupta published an anthology of his studies in India’s Popular Cinema in 1991. Among the 11 chapters of this work, two specifically focused on MGR and his contemporary N.T. Rama Rao, a Telugu movie star who also had appeared in Tamil movies in 1950s and early 1960s. Rama Rao also followed MGR’s steps into Indian politics and became the Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh in 1983. Das Gupta’s analysis was riddled with (1) factual errors on the career of MGR, as well as the name of MGR itself, (2) name calling, and (3) condescension of Tamil Nadu masses. This is nothing new among the Indian pedants who had subscribed to Communist-Socialist ideology. I quote his thoughts below, and offer my comments to that.

Thought 1: “Men do become gods in the cinema; but some of the cinema’s gods too have become men of power on earth of avataras of Krishna or Rama. Indeed the two of them who promised, and created, something of the illusion of realizing Ramrajya, both bear his name – Madanapally (sic!) Gopala Ramachandran in Tamil Nadu and Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao in Andhra Pradesh. The process of equation of myth with fact, the easy movement of the mind between the two, is helped by the nature of visual perception in pre-industrial societies.”

First, the term ‘Ramrajya’ (i.e, the ideal kingdom ruled by Lord Rama) was promoted by none other than Mahatma Gandhi, in pursuing his goal of Indian independence. Thus, the ‘Ramrajya’ concept predates the entry of both MGR and Rama Rao into cinema. In fact, Gandhi’s emphasis on religion is suggested as one of the reasons for Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948) to raise the call for a separate Muslim dominant Pakistan state. Gandhi was the first to promise and create an illusion of realizing Ramrajya! Secondly, not all actors who carried the ‘Rama’ name were able to achieve successful careers in either cinema or politics, even if they had bothered to indulge in politics in Tamil Nadu or Andhra Pradesh. For example, there were four ‘Ramaswamys’ in Tamil movie world who were contemporaries of MGR. These were, K.R. Ramasamy, V.K. Ramasamy, ‘Friend’ Ramasamy and Srinivasa Iyer (Cho) Ramaswamy, and two ‘Ramachandrans’ (T.R.R and T.K.R). Why none of them were able to execute the ‘Rama’ magic among the Tamil Nadu masses? Consider the case of comedian Cho Ramaswamy, who simultaneously indulged in cinema and politics, like MGR, especially making fun of latter’s policies? Why he couldn’t attract mass support and rise to the top like that of MGR? Thus, bearing a ‘Rama’ name was not a talisman for the career success for either MGR or Rama Rao.

Thought 2: “Only in high-literacy areas subjected to Western thought structures, especially rationalism and Marxist materialism, such as the states of Kerala and West Bengal, does the cinema audience have a ready ability to separate myth from fact. Prem Nazir held the Guinness Book record for having made the largest number of films of any actor in the world (more than 600), but when he developed political ambitions, the people of Kerala made it quite clear that their matinee idol in the cinema would not be acceptable as their political chief. This is in direct contrast to M.G. Ramachandran in Tamil Nadu or N.T. Rama Rao in Andhra Pradesh.”

Das Gupta seems ignorant of one critical fact that actor Prem Nazir (1926-1989) was a Muslim by birth! His birth name was Chiriyinkil Abdul Khader! In the history of Kerala state, only one Muslim (C.H. Mohammed Koya) had held the chief ministership for a short period of 51 days, in 1979. I consider this as the main reason, why Prem Nazir’s political horse couldn’t fly in Kerala. Despite the so-called ‘rationalism and Marxist materialism’ in which Kerala state seems to be drenched, old fashioned religious intolerance among voters still reign high!

Thought 3: “MGR’s image was more consciously and meticulously planned and executed than Hitler’s or Stalin’s cinematic strategy. Leni Riefenstahl was too talented to be useful enough to Hitler for any length of time; Stalin had no end of trouble with geniuses like Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Dovzhenko, and had no joy out of the mediocre. MGR’s directors, on the other hand, served his every wish faithfully, with the result that when MGR stood before the electorate, his victory was a foregone conclusion.”

As is the wont of Communist-Progressive idealogues, Das Gupta indulges in name calling, in comparing MGR’s movie strategy to that of Hitler and Stalin. In fact, when one studies the Soviet film development during Stalin’s era, following facts become evident about which Das Gupta seems ignorant. I selectively quote from Peter Kenez’s report in ‘The Oxford History of World Cinema’ (1996).

(1) “Socialist realist novels and films followed a master plot: the hero, under the tutelage of a positive character, a Party leader with well-developed Communist class-consciousness overcomes obstacles, unmasks the villain, a person with unreasoned hatred for decent socialist society, and in the process himself acquires superior consciousness – that is, becomes a better person.”

(2) “A recurrent theme in films dealing with contemporary life was the struggle against saboteurs and traitors.”

(3) “According to official doctrine, it was the script-writer, rather than the director, who was the crucial figure and ultimately responsible. Stalin thought that the director was merely a technician whose only task was to position the camera, following instructions already in the script.”

In fact, all most all the MGR’s films followed the above three strategies to the dot, which was appropriate to the Soviet society. Rather than the director, MGR relied on a good script writer for his movies. As I have indicated in part 11 of this series, 11 out of 25 of his movies in the 1950s decade were scripted by DMK party affiliates Karunanidhi (5 movies), Kannadasan (4 movies) as well as Asaithambi and Rama Arangannal (2 movies) to propagate DMK ideology.

Criticism of M.S. S. Pandian (1992)

M. S. Pandian also has made identical criticism on the formula of MGR’s movies to that of Das Gupta. Pandian had written as follows:

“The social universe of the MGR films is one of asymmetrical power. At one end of the power spectrum are grouped the upper caste men/women, the landlords/rich industrialists, the literate elite and, of course, the ubiquitous male – all of who exercise unlimited authority ad indulge in oppressive acts of power; at the other end of the spectrum can be found the hapless victims – lower caste men, the landless poor, the exploited workers, the illiterate simpletons and helpless women.”

Then, he identified MGR role as, “the subaltern protagonist, in the course of the conflict, appropriates several signs or symbols of authority/power of those who dominate…Three signs repeatedly and prominently appear in MGR films. They are (a) the authority to dispense justice and exercise violence, (b) access to literacy/education, and (c) access to women.”

Plot wise, MGR’s movies hardly vary from either the Soviet era films of Stalin period, or that of cowboy Westerns by John Wayne. Thus, my earlier comments do stand and need not be repeated again. One additional criticism of Pandian was that of MGR cavalierly changing the ending of movies to his whims. Specifically, Pandian made the following comment.

“’Oli Vilakku’ (1968), which is the Tamil remake of the extremely popular Hindu film ‘Phool Aur Patthar’ and was produced by S.S. Vasan. In the Hindi original, featuring Dharmendra and Meena Kumari, the hero marries the widow at the end. But in the Tamil version, the ending of the film was changed at the instance of MGR himself, so that the widow dies a tragic death and the hero weds an unmarried woman.”

Movie critics, unversed with the reality of movies as a business commodity, do carp too much on the realism of the plot. Here is a gem from Das Gupta: “In order to mature, the cinema must pass through the litmus test of realism, if only to reject it later, after proving its ability to distinguish fact from myth. This aspect of cinema has remained almost completely outside the scope of India’s popular film. All popular cinema tends towards melodrama by telescoping the process in order to stress the high points of drama; but within that constraint, the best examples of it are able to provide non-verbal resonances, often of a high order.” But his own daughter, Aparna Sen (as a director) did have business sense when she commented, “All I want is that my producer should never lose money on the kind of films I make. I would be happy if he came back to me and asked me to direct another feature.” in an interview in 1983.

One can cite that in Hollywood movies there had been precedence flouting realism for imagination and for such twisting of movie plots at the end, according to the whims of the hero. I provide two examples, from the autobiographies of Charlie Chaplin and Marlon Brando.

Chaplin had the following comment on portraying realism in movies. “I was depressed by the remark of a young critic who said that ‘City Lights’ was very good, but that it verged on the sentimental, and that in my future films I should try to approximate realism. I found myself agreeing with him. Had I known what do now, I could have told him that so-called realism is often artificial, phoney, prosaic and dull; and that it is not reality that matters in a film but what the imagination can make of it.” Now, ‘City Lights’(1931) – a silent film at that – with few simple sets and fluid editing is deemed as one of the best movie classics.

Pandian, while conceding that “MGR was well-versed in every aspect of film making – direction, camera, music, editing etc., and he utilized all these skills in constructing an image for himself” also carps that “According to Cho Ramaswamy, a co-actor of MGR in a number of films, ‘All the fights in his [MGR’s] films were personally shot and edited by him’ ”

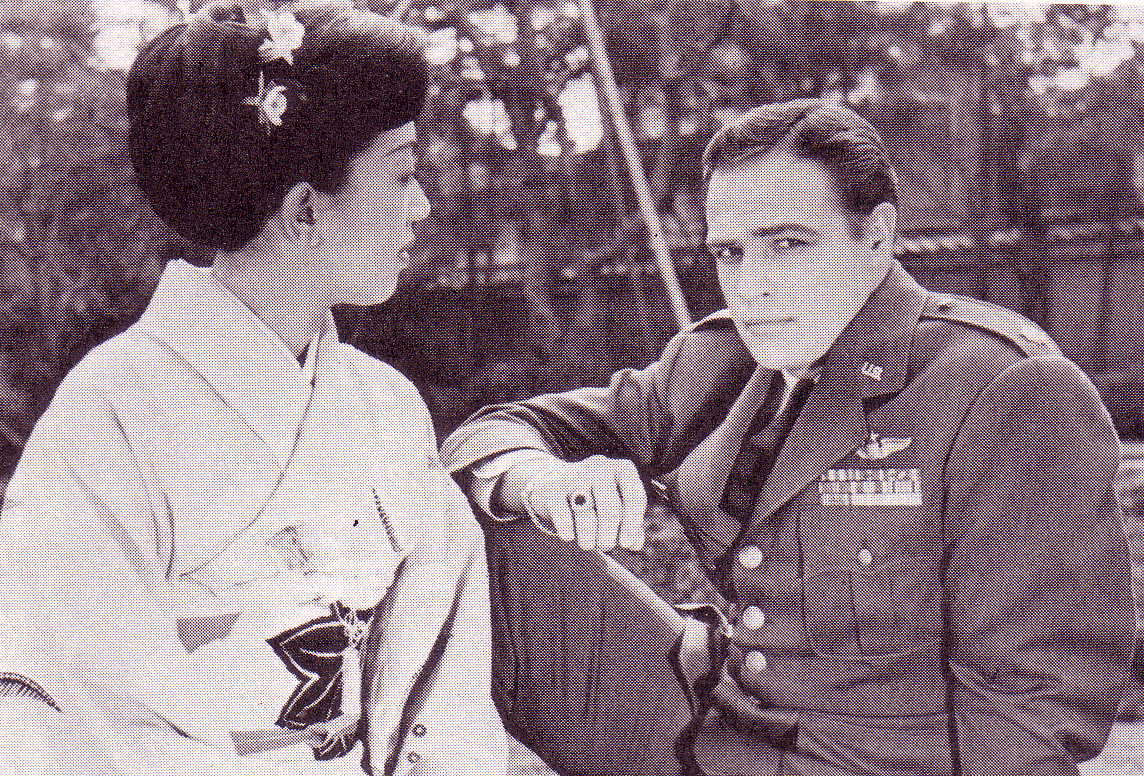

My comment is nothing but, ‘So what?’ That’s how true professionals, like Chaplin, operate. Marlon Brando did provide the reasons why he wanted to change the ending of one of his movies, ‘Sayonara’, to be in line with his own policy and thought. ‘Sayonara’ movie was based on James Michener’s novel by the same name. To quote,

“I read the novel, Sayonara, which was set in postwar Japan, and thought it raised interesting issues about human relations, but I didn’t like the script. In the script and the novel, the character [Joshua] Logan wanted me to play, Major Lloyd Gruver, a Korean war-ear U.S. Air Force pilot, fell in love with a beautiful Japanese woman, Hana-ogi, a member of a distinguished and elite dance troupe, but their interracial romance was doomed by the tradition in both cultures of endogamy, the custom of marrying only within one’s own race or caste. In accepting this principle, I thought the story endorsed indirectly a form of racism. But with a different ending, I thought it could be an example of the pictures I wanted to make, films that exerted a positive force. I told Logan, I’d do the picture if the Madame Butterfly ending was replaced by one stating that there was nothing wrong with racial intermarriage, and that it was a natural outcome when people fell in love. I wanted the two lovers to marry at the end of the picture, and Logan agreed.

But once we were in Japan, I discovered that Josh was burdened with an overwhelming depression that made him unable to function. I ended up rewriting and improvising a lot of the picture, and we had to limp along as best we could.”

Again, Marlon Brando emphasizes the point, what MGR would have agreed whole heartedly. He had written, “I wanted to make pictures that were not only entertaining but had social value and gave me a sense that I was helping to improve the condition of the world.”

If two of the much respected legends (Chaplin and Brando) do agree with MGR’s sense of taste in Tamil movie making, then one wonders about the degree of ignorance among upstart critics like Das Gupta, Pandian and Sivathamby!

Film Snobs as Critics

The problem with the Indian movie critics was that they came to subscribe to the ‘auteur theory’ passionately in late 1950s, following the success of director Satyajit Ray in the international arena of films. Tamil movie critics tuned in to identify the auteurs among Tamil cinema and did check C.V. Sridhar, K.S. Gopalakrishnan, A. Bhimsingh and K. Balachander in 1950s and 1960s. Among these, only K.S. Gopalakrishnan had co-directed one MGR movie ‘Panakkari’[Rich woman, 1953], an adoption of Anna Karenina plot, which flopped in box office. Though he didn’t direct MGR, K. Balachander (born 1930) was initially introduced to Tamil movies by him, when MGR offered script-writing role for one of his movies Theiva Thai (1964).

Kamp and Levi described the ‘auteur theory’ as, “Immutable tenet of film theory that holds that the director, rather than the screenwriter, producer or star, is the ‘author’ of a film. First posited by Francois Truffaut in Cahier du Cinema in 1954, Americanized by Andrew Sarris in Film Culture in 1962, and then ridiculed by the gad fly Pauline Kael, in Film Quarterly in 1963. Though the debate over the auteur theory’s worth subsided long ago, snobs still brandish the theory to make cases for the greatness of such unworthies David Fincher.”

Kirk Douglas (born 1916), one of the few still living legends of Hollywood’s studio era, had commented on the auteur theory in his autobiography, as follows: “I’ve always been intrigued with this auteur theory that came across the ocean from Europe and contaminated our system. The auteur theory holds that the director is the creator of the film. A film is a collaborative effort. It is rare that a movie is ever one person’s film. Perhaps people like Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Woody Allen, Barbra Striesand, who write, direct, and star in their pictures, are entitled to that billing. Yet even they need help – producers, casting directors, editors, technicians, location managers, other actors.”

Das Gupta in his analysis on MGR’s movie career, makes abysmal factual errors, which revealed his utter lack of facts-checking skills. He had noted. “The first film in which MGR played the lead was written by Karunanidhi in 1950 and called Meruda Nattu Ilavarasi”. This was wrong, as I had indicated previously. The first MGR- Karunanidhi collaboration and the film in which MGR played the lead was in 1947, in the movie ‘Rajakumari’. Then, in more than one occasion of his book, Das Gupta mentions that MGR had acted in 292 films in his long career. This was also wrong. MGR’s total tally was only 133, between 1936 and 1978.

If Das Gupta had bothered to the study the cinematic and political careers of Rama Rao and MGR in depth, he might have inferred that superficial similarities are only a few; but, more differences can be noted in their preparation for political careers and how their political careers ended. I provide a short paragraph that appeared in 1982 in an anonymous commentary in Link magazine.

“From the manifesto released by the Telugu Desam Party a day or two prior to the first State level meeting, it was clear that the new regional party was quite different from the ‘Self Respector’ movement launched by E.V.Ramaswami in Madras some decades ago: not has it anything in common with the DMK or even the AIADMK. More than that NTR himself has nothing in common with either the great Periyar, or Annadurai or even with MGR.”

MGR joined Annadurai’s DMK party in 1953 and was a member of it until October 1972. Karunanidhi, who followed Annadurai to leadership in 1969, threw out MGR in 1972 on disciplinary grounds. In consequence, MGR formed his own party and named it after Anna, as Anna DMK (ADMK).

John Wayne and MGR

To the taunt of snob critics (Das Gupta and Pandian) that all MGR movies have the ‘same plot and same ending’, his Hollywood contemporary John Wayne had offered a typical answer. “I’ve never had a goddam artistic problem in my life, never, and I’ve worked with the best of them. John Ford isn’t exactly a bum, is he? Yet he never gave me any manure about art.’ And again, “I play John Wayne in every part regardless of the character, and I’ve been doing okay, haven’t I?” It could well be, the euphemistic word ‘manure’ was not the one which John Wayne would have used; it probably was ‘softened’ posthumously by the editorial desk of ‘Guinness Movie Facts & Feats’ for propriety, and in fact refers to ‘shit’ in English slang. MGR would have said the same thing. He did work with auteur directors of Tamil movie industry in his earlier years, beginning with Ellis Dungan, Raja Chandrasekar and A.S.A. Samy. In his closing years of movie career (in 1970s), even C.V. Sridhar came to MGR to direct two of his movies, specifically for financial reasons. More about this later!

It is also appropriate to include an observation by Katherine Hepburn, the heroine of Wayne’s ‘Rooster Cogburn’ movie. Both were of same age and belonged to the same Hollywood super-star cohort. Hepburn, in her autobiographical memoirs had noted in her inimitable clipped-style of talking, “John Wayne is the hero of the thirties and forties and most of the fifties. Before the creeps came creeping in. Before, in the sixties, the male hero slid right down into the valley of the weak and the misunderstood. Before the women began dropping any pretense to virginity into the gutter; with a disregard for truth which is indeed pathetic. And unisex was born. The hair grew long and the pride grew short…” What Katherine Hepburn had said of Wayne, do apply to MGR as well, with a marginal alteration in the first sentence, as follows, ‘MGR is the hero of the fifties and sixties and most of the seventies.’ in Tamil movies.

Katherine Hepburn continues further, about Wayne: “Politically he is a reactionary. He suffers from a point of view based entirely on his own experience.” This was same with MGR too. Then, on the acting talent of Wayne, Hepburn had this evaluation: “As an actor, he has an extraordinary gift. A unique naturalness. Developed by movie actors who just happen to become actors. Gary Cooper had it. An unselfconsciousness. An ability to think and feel. Seeming to woo the camera. A very subtle capacity to think and express and caress the camera – the audience. With no apparent effort. A secret between them.” Again, each ‘sentence’ does apply to MGR’s style of acting as well.

Sources

Anon: The balloon that failed to go up. Link, May 2, 1982, pp. 16-17. [on N.T. Rama Rao’s entry into politics with his Telugu Desam party]

Marlon Brando: Brando – Songs My Mother Taught Me, Century, London, 1994, p. 244-245.

Charlie Chaplin: My Autobiography, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1964, p. 377.

Chidananda Das Gupta: The Painted Face – Studies in India’s Popular Cinema, Roli Books Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi, 1991.

Kirk Douglas: The Ragman’s Son – An Autobiography, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1988, p. 323.

Katherine Hepburn: Me – Stories of My Life, Penguin Books, New York, 1992, pp. 203-206.

David Kamp and Lawrence Levi: The Film Snob’s Dictionary, Broadway Books, New York, 2006, p.9.

Peter Kenez: Soviet Film under Stalin, in Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (Ed), The Oxford History of World Cinema, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996, pp. 389-398.

M.S. S. Pandian: The Image Trap – M.G. Ramachandran in Film and Politics, SAGE Publications, New Delhi, 1992, p. 42-43, 90.

Patrick Robertson: Guinness Movie Facts & Feats, Guinness Publishing Ltd., Enfield, Middlesex, 4th ed., 1991, p. 93.

Sunil Sethi: Breaking Out and Breaking Even, India Today, Feb.15, 1983, pp. 120-125.