by Sachi Sri Kantha, February 24, 2014

Then, as of now, carping cinema critics have had a couple of serious problems. Their tone of criticism was nothing but crass elitism, and on top of that they were also ignorant about the logistics and economics of movie making. To counter such criticism, I offer the following details about the status of movie production in India in 1950s. To understand how MGR shaped his career in Tamil movies, these details are vital indeed.

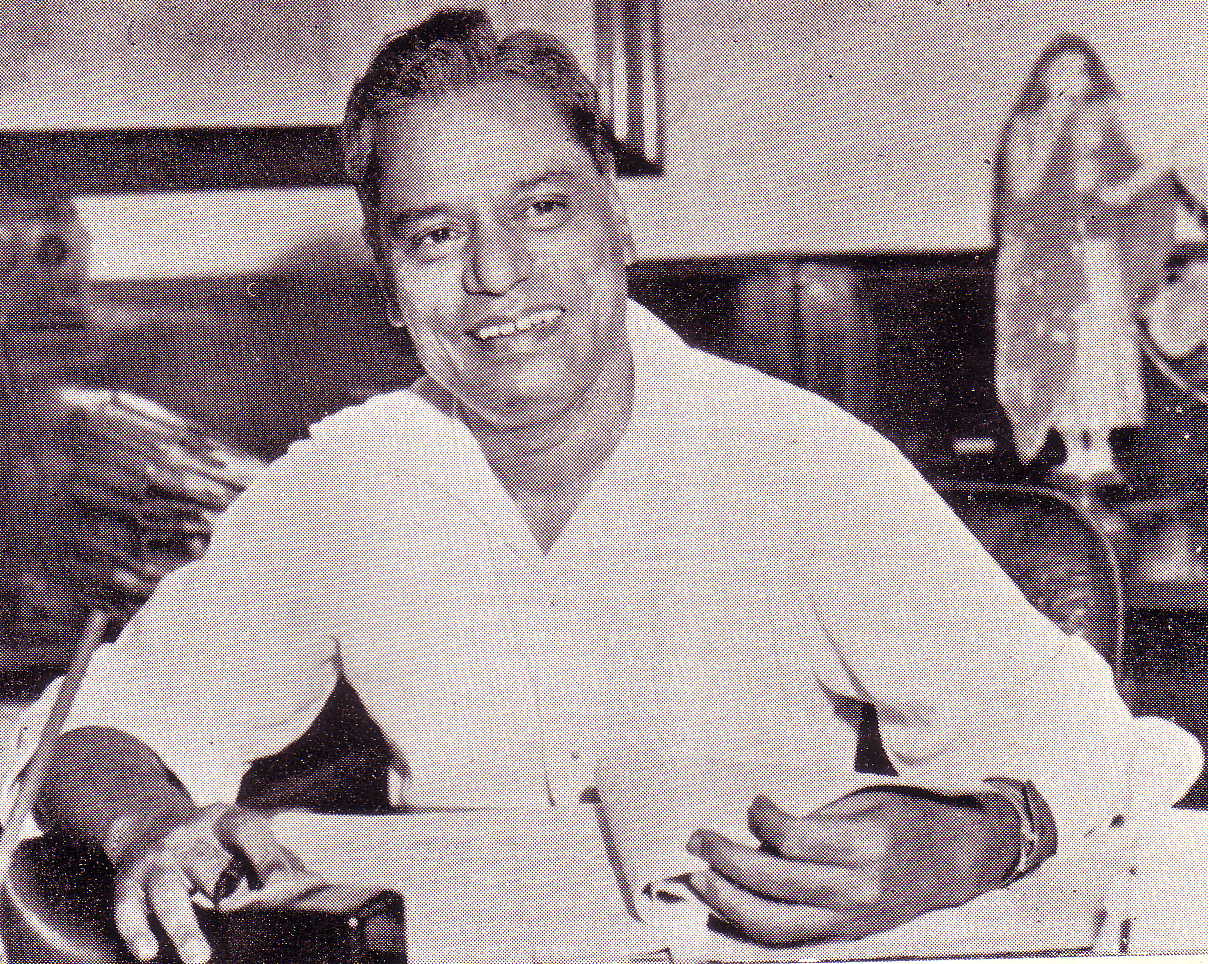

Mr. S.S. Vasan (1903-1969)

Thiruthuraipoondi Subramanian Srinivasan (known popularly by shortened version, S.S. Vasan, 1903-1969) was one of India’s print industry and movie moguls from Brahmin stock. Like MGR, he also had lost his father at an early age. By perseverance of his mother and his own diligence, he made it to the top. I’m not aware whether a good biography of him exists in English, other than a short, humorous memoir of 47 pages, by writer Ashokamitran (a pen name, b. 1931) that appeared in 2002. Tamil movie historian Randor Guy also briefly annotated Vasan’s career in one chapter of his 1997 book. Ashokamitran had merely reached 20, when he joined the Gemini Studios, headed by Vasan, who employed around 600 individuals in his studio. While recollecting the incident when Vasan (as the boss) chopped music director C. Ramachandra’s score for lack of tempo despite the pleadings from Ramachandra, Ashokamitran humorously observed the personality of Vasan; “Vasan could make even a railway time-table have tempo. Only, with such tempo, you may not get the timings right all the time.”

MGR had treated Vasan as a patron figure for his kindness and helpful attitude to suffering artistes like him. Thus, Vasan does receive appreciative mention in MGR’s autobiographical chapters 116, 117 and 118, for assisting him and his third wife V. N. Janaki when they had a serious legal issue with the latter’s then ‘guardian’ in late 1940s. For propriety reasons, MGR had omitted identifying this ‘guardian’ by name in 1972. He had identified this person, with a phrase ‘a person like a guardian’; he does use the English word ‘guardian’ rather than the appropriate equivalent Tamil word. MGR had left for the readers to guess, who this ‘guardian’ was, who also gave much trouble to both of them. My guess, based on circumstantial evidence from MGR’s descriptions of this person, was it’s none other than Janaki’s first husband Ganapathi Bhat.

Film Seminar of 1955

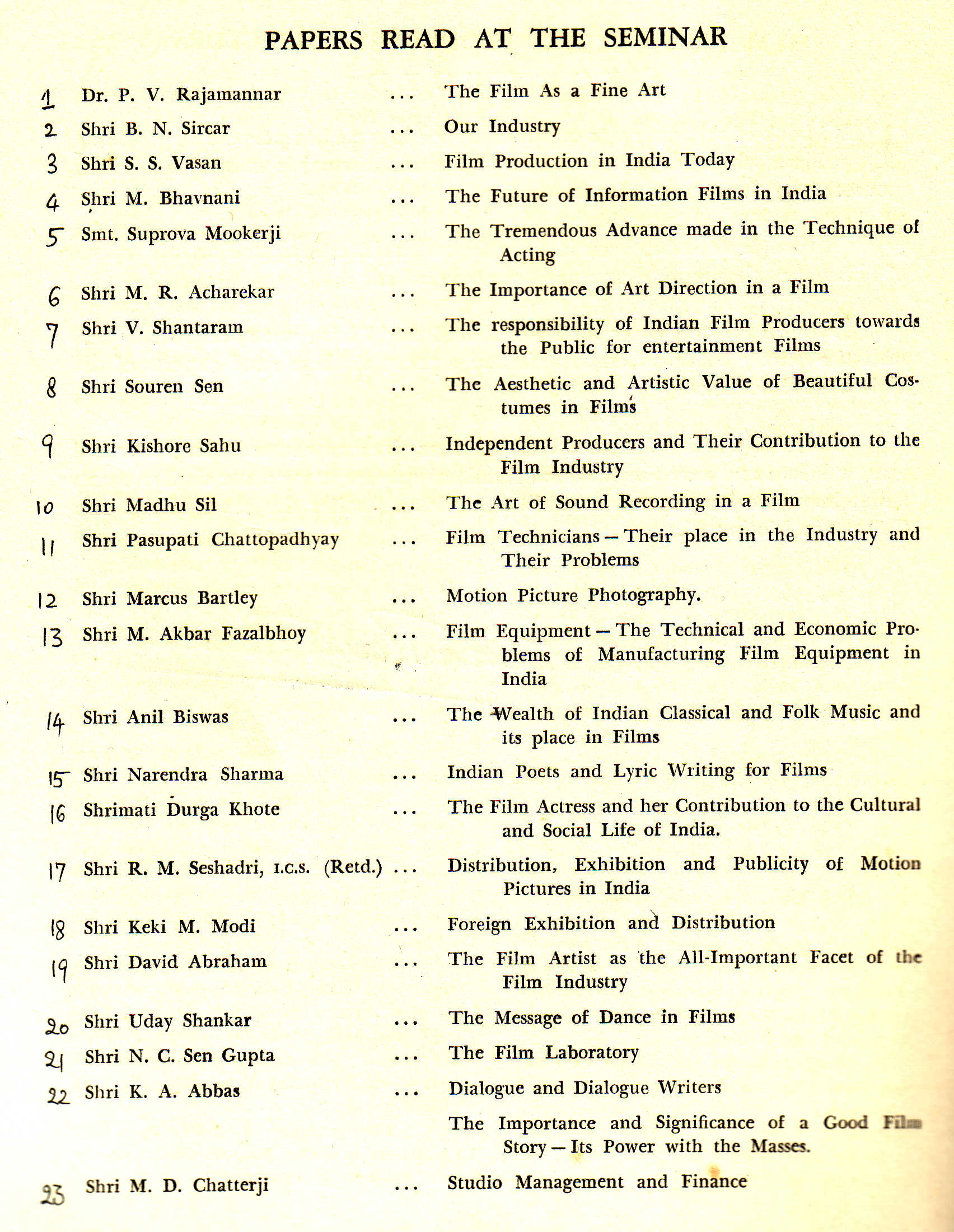

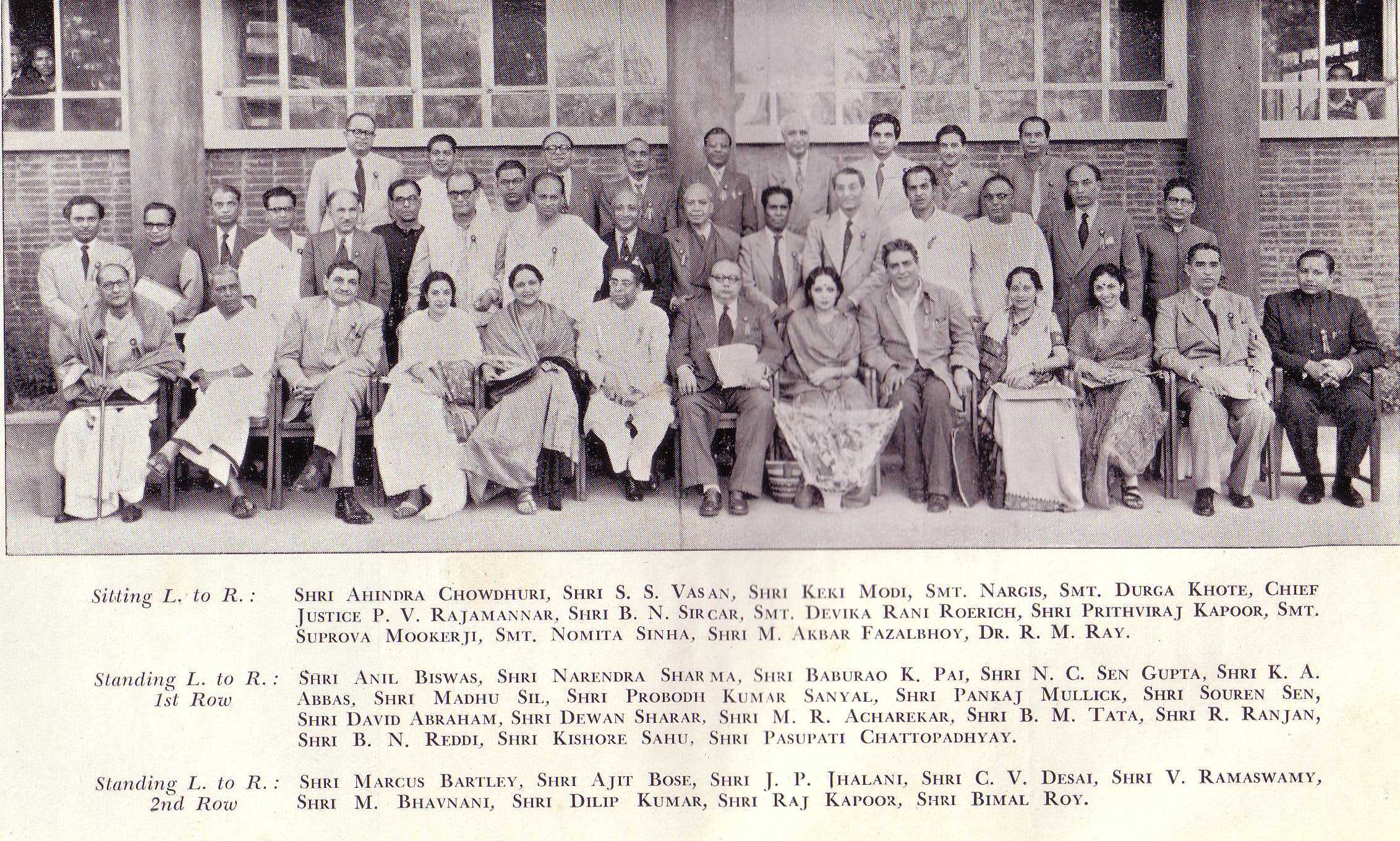

A Film Seminar event, sponsored by the Sangeet Natak Akadami, was held in New Delhi from February 27th to March 4th in 1955. It was inaugurated by the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Over 40 leading personalities of Indian movie industry from three centers of movie industry (Calcutta, Bombay and Madras) and New Delhi participated in it and 23 papers were presented. Then, there were discussions on each of these presentations by other participants. Here is the list of participants.

Bengal: M.D. Chatterji, Debaki Kumar Bose, Suprova Mookerji, Ajit Bose, Probodh Kumar Sanyal, Pankaj Mullick, Pasupati Chattopadhyay, Nomita Sinha, Ahindra Chowdhuri, Modhu Sil, Souren Sen, Dr. R.M. Ray.

Bombay: Durga Khote, Nargis, V. Shantaram, Bimal Roy, Kishore Sahu, Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar, Anil Biswas, K.A.Abbas, Dewan Sharar, B.M. Tata, M.R. Acharekar, K.M. Modi, Baburao K. Pai, M. Akbar Fazalbhoy, David Abraham.

Delhi: Uday Shankar, Narendra Sharma, M. Bhavnani, R. Ranjan, Seth Jagat Narain, Jagannath Prasad Jhalani, C.V. Desai, Nirmala Joshi.

Madras: S.S.Vasan, B.N. Reddi, R.M. Seshadri, N.C. Sen Gupta, V. Ramaswamy, Marcus Bartley, Y.G. Doraiswamy.

I provide a scan of the photo taken at the Film Seminar nearby. Senior personalities were seated. S.S.Vasan is seated 2nd from the left. In the 1st raw (standing), one can recognize R. Ranjan (4th from right). In the 2nd raw (standing), notable Hindi actors Dilip Kumar (3rd from right) and Raj Kapoor (2nd from right) can be seen.

Though MGR was not a participant, his then rival for the ‘action-hero’ slot in Tamil movies R. Ranjan did participate as a representative from Delhi. Madras contingent was led by mogul S.S.Vasan, who was also a patron figure for MGR. Ranjan himself had starred in Vasan’s successful production Chandralekha (1948) as a villain. The hero in this movie, was MGR’s mentor, M.K. Radha (see, Part 12 of this series). On February 28th, 1955, Vasan presented his lengthy paper, ‘Film Production in India Today’. On the previous day (Feb.27, 1955), prime minister Nehru while inaugurating the Seminar had expressed his views on Vasan’s paper, because the latter had sent a presentation copy to Nehru, probably as a courtesy. One is not sure, whether Nehru himself requested it from Vasan to prepare his inaugural talk. Nevertheless Vasan’s lengthy presentation had a total of 60 items, in the printed report.

‘Film Production in India Today’ by S.S. Vasan

I provide a synopsis of the issues Vasan delivered, in his own words, below.

Item 5: A film is the end-product of the labours of a number of artist-technicians. It is a symphony of cooperative effort. Actors, directors, art directors, script writers, cameramen, soundmen, editors, all have to work together under the leadership of a producer for a common object.

Item 10: The great majority of the cinema audiences tend to favour melodrama and other easier forms of emotional expression.

Item 25: India has produced about 7,000 feature films so far. It has 73 studios, situated chiefly in Bambay, Calcutta and Madras. There are about 3,000 cinemas. Well, what do these figures represent? To know if these figures are encouraging or not, one must appraise them on the background of our vast population. India’s population is over 360 million. In other words we have only 8.5 theatres for a million people. This is the lowest figure for any progressive country in the world. The average number of theatres for a million people in America and England is said to be over 125. Our number is 1/16th of that in those two countries, as far as theatres are concerned…

Item 27: The most important reason is, I think, that public men and philosophers have neglected the careful study of the cinema. When they think of the cinema, they think only of sex and immorality; they do not think of the good things about the cinema. Many of them seem to have a closed mind on the subject. They are suffering under a complex, caused by the age-old prejudice of the so-called ‘genteel’ folk towards any kind of show business and the men engaged in it…

Item 28: The main reason for this prejudice is perhaps that members of this profession, unlike those engaged in most other professions, always depend on public support and patronage for their very existence. The showman, like the politician, exists only at the pleasure of the public. He is always dispensable, not indispensable….

Item 34: What are the uses to which the cinema can be put? It can be used as a powerful supplementary aid in education. It can be and is, as a matter of fact, to a very large extent, used as a means of propaganda, publicity and advertisement…

Item 35: I take it that it is agreed on all hands that recreation and entertainment are almost as important as food, clothing and shelter…

Item 42: …the general impression that film makers make huge profits. It is not realised that the majority of film producers lose money in their productions. The number of producers of unsuccessful pictures is legion, and their financial mortality is unknown, because dead pictures, like dead men, tell no tales.

Item 45: …Because the cinema is said to corrupt morals, and does not educate, it is not allowed to expand freely. Because cinema-man is said to be making lots of money, he is taxed heavily. Government’s attitude appears to me to be: ‘I won’t allow you to grow. I will also tax you heavily!’…

Item 49: As far as I can see, friends, this is indeed a vicious circle. The quality of films does not improve because the industry is not allowed to grow. The industry is not allowed to grow because the quality of films has not improved!…

Item 51: The Central Government also could contribute liberally to the industry’s growth in its own way, i.e., by administering its censor code liberally and not literally…

Item 54: Censorship was imposed during the British rule to see that nothing was allowed which would upset the then system our government. But now we are a free nation. There is no question of upsetting our Government. Hence the State-sponsored system of censorship must slowly fade out, giving place to self-censorship by the industry itself, as in our progressive countries.

There is no doubt that Vasan, as a representative of movie industry, presented his case strongly and effectively. But, what was the reaction from the Indian government? Prime- minister Nehru’s thoughts were not conciliatory on what Vasan had pleaded.

Prime Minister Nehru’s Inaugural Address (of Feb.27, 1955)

I quote the relevant two paragraphs of Nehru’s address in which he responded to Vasan’s plea.

“An eminent figure in the film world, Mr. Vasan, sent me some days ago a copy of the address which he proposes to deliver at some stage of this Seminar. Well, it was lying about with me. Again, when I heard of these controversies, I tried to find time to read through it, although normally, I may confess I would not have read it. So I read it. I might tell you, I did not find anything terrible in it. In fact it was quite mild. Possibly, if I had been writing something like that, I might have used stronger language in regard to various matters (applause). That does not mean that I agree with all that Mr. Vasan said (laughter), not at all. But the point is, these are some of the subjects which are raised, obviously deserving careful study and consideration. One subject, for instance, Mr. Vasan and the industry are, no doubt, greatly interested in and he talks about, is the reduction or abolition of entertainment tax. About that, I propose to say nothing at all except that I am not convinced by Mr. Vasan’s argument. I am not talking about the rate of it – I don’t know what it is in various places. But I do not see at all, broadly speaking, why entertainment should not be taxed. To what extent they should be taxed is a different matter – I cannot say, it may be more or less.

Another subject which Mr.Vasan has mentioned – there are several – is something about censorship. Now this is a difficult subject so far as I am concerned, because I start with a certain presumption against censorships; I am, I am sorry to say, still affected considerably by my old 19th century traditions in regard to such matters. So I do not take favourably to too much restriction or too much censorship. On the other hand, it is quite absurd, it seems to me, for anyone to talk about unrestricted liberty in important matters affecting the public, to leave people to do what they like. Suppose, as might well happen, that the production of the atomic bomb became cheaper and simpler. Well, are we going to allow, in the name of full liberty of the individual, everybody to carry an atom bomb with him in his pocket? Certainly not. So this question of some high principle in favour of censorship or against it has no meaning to me except that broadly speaking one should not restrict and interfere. I accept that. But one has to interfere, the State has to interfere to some extent. To what extent is another matter.”

While reading the lecture made by Vasan and Nehru’s response to it simultaneously in totality, after 49 years, one can easily infer that Nehru was skillful in deflecting serious issues. His logic of comparing Vasan’s plea for less censorship in movies to that of permitting ‘pocket atom-bombs, if they become available’ was inept and like comparing apples and oranges!

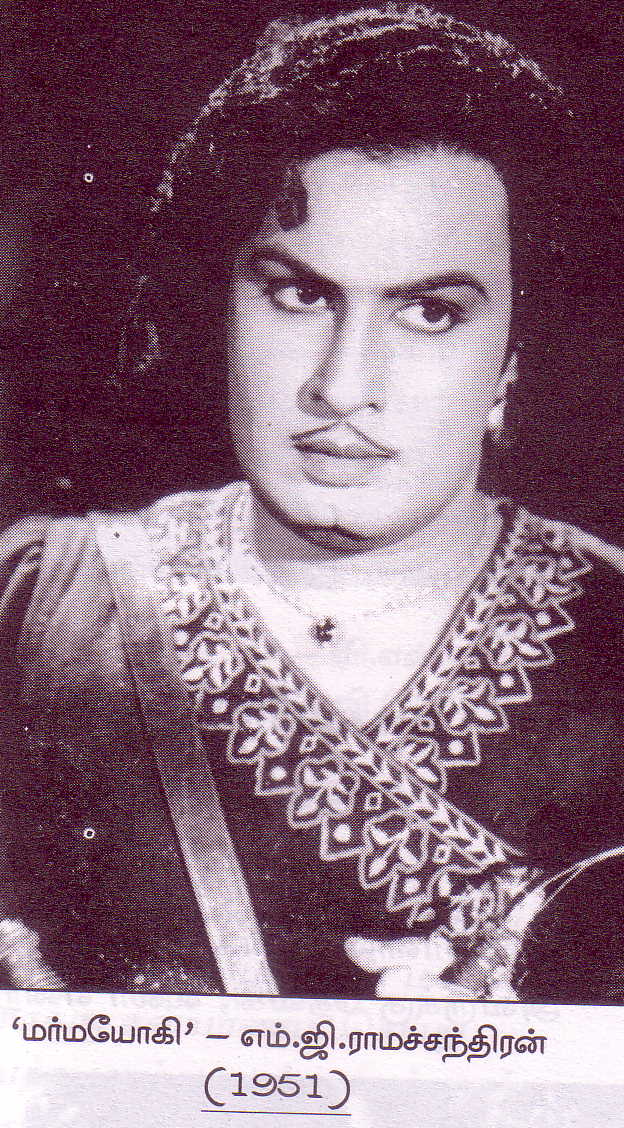

The vagary of Indian censorship style was experienced by MGR too. His 1951 movie ‘Marma Yogi’ (The Mysterious Mystic) received an ‘Adults Only’ certificate (a first for a Tamil movie) for an unconvincing reason that the story plot involves ‘a ghost’! Considering this fact, Nehru’s defense of the sensibilities of Indian movie censors in 1955 with ‘pocket atom-bomb’ analogy has to be taken as nothing but a joke! The heroine of ‘Marma Yogi’ movie Anjali Devi (1927-2014) died last month (Jan.13, 2014) at the age of 86. And it was the first movie which had MGR- Anjali Devi combination. Since then, the same MGR-Anjali Devi pair worked successfully in three more movies, Sarvadhikari (The Dictator, 1951), Chakravarthi Thirumakal (Princess of the Emperor, 1957) and Mannathi Mannan (King of Kings, 1960). About Anjali Devi’s status in early 1950s, MGR had reminisced passingly in an early chapter of his autobiography as follows: “I was acting with big-name actresses Mrs. Anjali Devi and Mrs. Bhanumathi in a few movies. They were acting in many films. Like now (~1970), I didn’t have many movies then. At that time, my earning was not even one tenth of what I receive now. Even though I didn’t have many movies, I was acting in dramas. Equally I was also involved in public events and public duties.”

Two additional presentations made at that 1955 Film Seminar, also deserves attention, for the numbers and thoughts included about the Indian film industry, which its elitist critics diligently ignore.

‘Independent Producers and their contribution’ by Kishore Sahu

Kishore Sahu (1915-1980), a Hindi actor who also carried additional hats as screen writer, producer and director, offered the following statistics for movie production in India, in 1955.

Kishore Sahu (1915-1980), a Hindi actor who also carried additional hats as screen writer, producer and director, offered the following statistics for movie production in India, in 1955.

‘India produces on an average 250 movies annually. Bombay led with 160 movies, with Calcutta 50 movies and South India 40 movies.’

‘There were about 300 movie producers, but only 60 studios. This meant, four out of every five producers were independents.’

‘Other involved players of movie industry were 600 movie distributors (including sub-distributors), 3,500 theater owners. Among these 3,500 were 800 ‘touring’ (tent) theaters.’

‘About 100,000 individuals were employed in various branches of the movie industry.’

Biggest problem facing the movie industry, was the lack of adequate finance. To quote Kishore Sahu, “There is no bank that lends us money. For the production of our pictures, we have to borrow from individual money-lenders at such a high rate of interest as is suicidal. That is the reason why 90% of our producers, or even more, sustain losses in most pictures. If a picture succeeds or clicks, the returns are published in all the newspapers and you think that the producers are minting money, that they are all rich. You judge the state of the industry from the figures of returns of one ‘hit’ picture. The returns of 90% of pictures or more are never published in any newspaper, and so you never know the truth.”

‘The responsibility of Indian film producers towards the public for entertainment films’ by V. Shantaram

Vankudre Shantaram (1901-1990) was an actor, director and producer of Hindi movies, who began his career as an odd job man and silent movie actor. Essence of his presentation is summarized below.

First, the film is a democratic art; it is not an individual expression of a writer, a sculptor, a painter, a photographer, a poet, a musician, a singer or an artiste; it is their collective contribution that makes a work of film art possible…It is also the task of the producer to raise money to make this venture possible and then market it. The film producer is thus in the most unenviable position of an artist as well as businessman; and this dual role that he has to play, puts a very heavy burden on his shoulders.

Secondly, as an artist, his creative work is open to criticism for its aesthetic shortcomings, and hence it is his duty to produce a picture worthy of the motion picture art; as a businessman, his paramount consideration is to ensure the popularity of the picture so that the lakhs [i.e., 100,000s] of rupees invested in the work of art are realized and he is in a position to make more pictures.

Thirdly, the financial burden is rather heavy. For in no other work of art is such a big investment called for. A motion picture’s cost varies from two lakhs [200,000] to twenty lakhs [2,000,000] of rupees today, so that his work may stand comparison with the product of the West, cannot afford to make pictures cheaply. So, naturally his primary responsibility is to recover the cost; and to fulfill that responsibility he has to make a picture which will please his customers – the picture-goers. He cannot afford to displease them.

Fourthly, what is the primary need of his customer? The picture-goer goes to see a motion picture for recreation, entertainment; that is his main objective…To please this audience is not an easy task, as it is composed of diverse sections of society with varying tastes and aptitudes.

Shantaram’s numbers for a cost of movie in 1950s, had been corroborated by poet Kannadasan in his 1977 diatribe against MGR. Kannadasan’s range was 700,000 to 2,000,000 Indian rupees.

S.S. Vasan’s additional thoughts

While flipping the 271 pages plus the Appendices of the Film Seminar report, it becomes evident that S.S.Vasan (more than any other attendee) did contribute more in the discussion sections of other presentations. I reproduce another vital contribution made by Vasan, which followed K.A. Abbas’s presentation, ‘The Importance and significance of a good film story – its power with the masses’. Khwaja Ahmad Abbas (1914-1987) was a successful script writer and director of Hindi movies. Vasan (as the editor of Ananda Vikatan weekly and as a movie producer) spoke,

“In my life as an editor of a paper for the last 30 years and as a film producer for 15 years, the presentation of stories for the public either through the printed paper or the printed celluloid has always confronted me. In the paper I edited, I always wanted that the stories printed should be entertaining and educative. That experience helped me when I entered the film business. Two words I always bear in mind: ‘Contrast and Compromise’. Whether in film making or in writing or in editing, these words are important. Contrast by itself is art. You will find in all art there is contrast. Whenever a thing goes up, it must come down. If there is black, there must be white. If you take the page of a paper, you will find an illustration and you will find printed matter. Even in god’s creation you will find contrast. That is art. And then compromise. I have always been obliged to compromise on art.

There is no such thing as finality in art. As long as the type of people who come to see your pictures are varied in their taste – their taste is not standardized – as long as you get literate and illiterate, common and uncommon, children, both men and women, as long as their tastes are varied, you have to compromise. You can take a particular theme, but you will have to slightly adapt that theme so that it could be enjoyed by the majority. One cannot be dogmatic. We must produce realistic stories on the screen or what purport to be for the benefit of the nation. You may do that, but you have to slightly compromise even there. If you make it too real, then it is not art. There must be idealism. Too much realism on the screen will only mean that in the final stage you take photographs of people as they are, without makeup. Therefore a touch of compromise is again there. Many types of films are being produced. It is all a question of the felt need.

Even Shri Abbas’s plea to educate the people on the problems of the nation and put the real lives of the nation on the screen is an answer to the need. He feels there is that need. Suppose there is a felt need for very fine entertainment to the people in my locality. I select a picture which is a hundred percent entertainment. I take it as a felt need. One produces pictures depicting present-day problems. Another produces pictures having rumba dances and music. You cannot say that the second producer is not doing a national service. After all, he might say, after a tiresome day, people want to relax and enjoy themselves. The film serves all types of people.”

Vasan was one movie mogul, who had correctly felt the pulse of illiterate Indian movie goers. Two decades before 1955, Paul Frederick Cressy (of Wheaton College, Massachusetts) published his questionnaire survey among 233 college students from Bombay, Madras, Nagpur, Lucknow and Lahore, in the American Journal of Sociology. The sample included 148 men and 85 women, and the study was done in the spring of 1931. Though he inferred that “No positive conclusions are possible from such a small sample, but they were gathered from representative university communities in widely separated sections of [British] India”, he reported that “Among 144 replies from male students, 56 indicate that they went simply out of a desire for recreation, 23 refer to educational reasons, and 58 combine these two motives.” Cressy’s conclusion was, “The main interests of Indian students in the movies seem to be generally similar to those of students in America. They go to the movies for amusement and recreation; they like pictures which provide adventure and humor.” It should be noted that this study sample belonged to ‘educated’ class [Those Indians who have had an English education], who patronized the Hollywood movies. Indian movies (silent films) of late 1920s and early 1930s had little appeal to this particular class, due to “poor technique [of movie making] and the low reputation of the actors.”

Despite technological advances, whether in 1930 or 1955 or 1980 or 2005, human tastes hardly change even though actors and producers arrive and leave in generational switch.

MGR’s angle in film production

It is evident from S.S.Vasan’s thoughts presented at the 1955 Film Seminar, MGR, as one of his protégés, had taken to heart what Vasan had implied on the functions of cinema in India. First, each movie should be a mix of education and entertainment for the so-called illiterate folks of India and elsewhere. Secondly, produced movies should not fail in earning a profit for the producers. Thirdly, if one has a hunch that a film project is not worth in earning a profit, it’s better to abandon it instantly rather than holding a ‘bombed’ movie finally. Fourthly, excess taxing by authorities leads to delicate handling of ‘black money’ which in turn boomerangs as ‘tax evasion’ claims in the industry.

Sources

Ashokamitran: My Years with Boss at Gemini Studios, Orient Longman Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi, 2002.

Cressy, P.F.: The influence of moving pictures on students in India. American Journal of Sociology, 1935 November; 41(3): 341-350.

Randor Guy: Starlight Starbright – The Early Tamil Cinema, Amra Publishers, Chennai, 1997.

Kannadasan: MGR in Ullum Puramum [MGR’s interior and exterior], Muttiah Publisher, Chennai, 1977.

Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen: Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema, new revised edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999.

Ray, R.M. (ed): Film Seminar Report 1955, Sangeet Natak Akadami, New Delhi, 1956, pp. 28-40, 73-78, 91-96.

Correction by Sachi: Relating to the personalities who attended the 1955 Film Seminar photo, I have inadvertently misspelled the word ‘row’; instead of ‘row’, it was written as ‘raw’. The error is regretted.

Sachi.. Very very nice effort and i could see the time and hardwork you put in to get these informations. Do you have or can you try to find the video footage of MGR getting national Award for Rickshawkaran.