Nadodi Mannan and Adimai Penn

by Sachi Sri Kantha, August 6, 2018

Bhanumathi, MGR and Chandrababu in ‘Nadodi Mannan’

In his cinematic career, MGR produced three movies, namely Nadodi Mannan (1958; Vagabond King), Adimai Penn (1969; The Slave Woman) and Ulagam Sutrum Vaaliban (1973; Globe-trotting Youngster). The first two movies were released while he was a ranking member of the DMK party. The third movie was released, after he was expelled from the DMK party, and formed his own splinter party Anna DMK in October 1972. In this chapter, I compare MGR’s first two own productions. MGR was 41, when Nadodi Mannan was released, and had reached 52, when Adimai Penn was released.

MGR’s thoughts on these two movies

First, let me provide what MGR had to say about these two movies in his autobiography. In chapter 111, titled ‘How Many Turns?’ that referred to what he considered as his critically and financially successful movies which shaped his movie career, MGR had listed 14 movies released between 1947 and 1971. Among these 14 movies, while ‘Nadodi Mannan’ was ranked as the 5th turn, ‘Adimai Penn’ was ranked as the 12th turn.

On ‘Nadodi Mannan’, MGR had written, “The one I produced, directed and acted in double roles. It turned out to be a grand hit. Due to that, my name became imprinted in the minds of movie fans, and impressed many in the art world.”

The description about this movie, as presented in the Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema is as follows:

“The good king Marthandan (MGR) is dethroned by the Rajguru (Veerappa) and replaced by a double, the commoner Veerangan (MGR again). Nakedly propagandist (e.g. colour sequences showing the red and black DMK flag and its rising sun party symbol), the film presents the good guys as waiting to overthrow the Rajgurus corrupt rule, a thinly disguised reference to the Congress Party. Inaugurating MGR’s personal political programme with songs like, Thoongathe thambi thoongathe (‘Don’t sleep, young brother’), its commercial successes was followed by a public reception for MGR by the DMK party, taking him in procession in a chariot drawn by four horses, thronged by the people. The chariot had a background of a rising sun on a lotus. At the beginning of the procession there were party volunteers carrying festoons. Elephants garlanded MGR twice’ (M.S.S. Pandian, 1992). Apparently Karunanidhi read out a poem he wrote about the film at the festivities. The film’s success was a turning point in the star’s film and political career marking him as the Puratchi thalaivar (revolutionary leader).”

The citation to Pandian’s 1992 study above, will be critiqued later in this chapter for it’s own propagandist notion of a Marxism-biased scholar and half-baked processing of available material in global cinema. In fact, the lyricist for the above cited hit song ‘Thoongathe thambi thoongathe’ sung by T.M. Soundararajan, was Pattukottai Kalyanasundaram with Communist leanings.

On ‘Adimai Penn’, MGR’s thoughts about it’s plot were as follows: “Not a historical story. Not a social story. Not also a story with exciting, cinematic effects. It’s story focused on some fundamental issues in the society, which makes the human spirit to suffer and weaken. But, it provided emphasis on the presence of powerful spine and one can straighten himself from bent angle due to self-confidence. Nevertheless, it had a few characters we usually don’t encounter. The hero was one who could win a struggle against a lion with a profound dose of mother love. In man or woman, the good and the bad domains do exist. But, to which domain one gives stress and focus, that particular domain will influence the personality of that individual. This was the nucleus of the heroine’s character.”

MGR described further more. “The belief of hero’s mother [a queen] portrayed in the movie was, in whatever sense her subjects become slaves, even if she was above those conditions, she should suffer similar humiliating experiences. She carried the movie’s title, ‘Slave Woman’. With such conflicting personalities in the movie plot, when it was released, it became a grand success. Thus, this turn was a big one [for me]. The Filmfare magazine from the Northern region graded it as ‘first class’ and awarded its prize to this movie.”

The plot of this movie, as presented in the Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema is as follows:

“Chengodan of Soorakadu lusts after Mangamma, the wife of the chieftain of Vengaimalai. When the woman cuts off her unwelcome suitor’s leg, he takes revenge by enslaving all the women of Vengaimalai and beheading all the men. Mangamma’s son Vengaiyyan (MGR), kept in a cell since childhood, escapes the slaughter and grows up to become an illiterate hunchback who, with the help of a slave woman, eventually reconquers his ancestral domain and kills the tyrant.”

Emblem of Em Jee Yar Pictures

Emblem of Em Gee Yar Pictures, 1958 and 1969

The above-cited reference to the emblem of Em Jee Yar Pictures, presented in the Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema (ie., colour sequences showing the red and black DMK flag and its rising sun party symbol) is rather oxymoronic! The first half of Nadodi Mannan movie is in black and white. The emblem of Em Jee Yar Pictures appear at the beginning. Thus, as it was presented in the screen, DMK flag appears simply as ‘black and white’, and NOT in ‘red and black’ [see the screen grab, presented nearby]. The Adimai Penn movie is in Eastman color, and thus the red and black DMK colors become visible. A notable feature here, is the engraving of Anna’s figure in the flag,

When this movie was released, three months had passed, since Anna’s death. MGR was still a member of DMK party lead by Karunanidhi, and three more years had to go, before MGR organized his own splinter party and named it Anna DMK. Nevertheless, one sees the premonition of MGR’s thoughts in presenting Anna’s figure in the party flag

One notable difference between the two movies: whereas MGR directed the Nadodi Mannan, he opted to hand over the directorial reign to one of his trusted hands, Kunnesari Shankar (1926-2006), for the Adimai Penn movie.

Comparison between Nadodi Mannan and Adimai Penn

Table – Comparison between MGR’s Own Productions

Above I provide a table, specially prepared for this chapter, which focus on the similarities and differences in 12 categories between Nadodi Mannan and Adimai Penn. Those who had studied MGR’s career previously in depth (such as Robert Hardgrave Jr, M.S.S. Pandian and R. Kannan) haven’t focused on the chronological setting on the plots of these two movies. As such, I prepared this table. I have no doubt that this table will be copied, reproduced, used and posted in the net by others in their Tamil language publications.

The main plot of the Nadodi Mannan movie was advocating regime change by people’s revolution, presented in the guise of costume adventure. This theme fitted neatly for 1958 in Tamil Nadu, when DMK was a fledgling party with meager resources, compared to the power holding Congress Party in the then Madras State and the Center in the New Delhi. A prominent party hand at that time was poet Kannadasan who shared the script-billing with MGR’s writer assistant Ravindar. Noticeably, Kannadasan was NOT among the lyricists who wrote the 11 songs for the movie [see the Table].

The composition of the songs for the movie, most of which became renowned hits, shouldn’t be underrated. There were 11 songs, which had a cumulated running time of a little over 1 hour, in a 3 hours and 40 min long movie was remarkable. One song in the movie was dedicated to the Dravidian unity (then the main political plank of the DMK party), in which segments with lines in Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam languages were incorporated. Apart from three lyricists who composed lines for these three languages (Vijaya Narasimha/Kannada, Narayana Babu/ Telugu and P. Bhaskaran/ Malayalam), MGR had solicited lyrics from 5 other distinguished Tamil lyricists: C.A. Lakshmanadas, Suratha aka Rajagopalan, M.K. Athmanathan, N.M. Muthukoothan and the young Pattukottai Kalayanasundaram. Among these, MGR considered the respected Lakshmanadas as one of his mentors in Tamil and had described an unpleasant experience he faced in confronting the poet-lyricist while he was young upstart and the magnanimity showed to him by Lakshmanadas. Thus, he was re-paying the debt he owned to Lakshmanadas. Muthukoothan was a fellow actor who belonged to MGR’s own drama troupe, imbibed in Dravidian politics. The young Kalyanasundaram was a Communist Party sympathizer, but MGR had high regards for his talent, based on his previous experience in working with Kalyanasundaram’s compositions in Mahadevi (1957) movie.

For the ‘Adimai Penn’, within 10 years, the state politics had changed drastically. DMK party had captured the ruling power after defeating the Congress Party in 1967 elections. Anna, the leader of DMK, also had died in February 1969. The theme of ‘Dravidian unity’ plank had been disposed to dust bin. Personally for MGR, though they collaborated occasionally in the movies due to compulsion from the producers and music directors, Kannadasan had drifted away from MGR and DMK. Thus, MGR opted to patronize other young lyricists Vaali and Pulamaipithan. Thus, for the ‘Adimai Penn’ movie, MGR chose the plot of mother worship in a costume-adventure setting. Mother worship [hard suffering mother is a universal theme, trawled by many movie directors in India and elsewhere like Japan. If one may propose it, a subtle sub-plot to the story was the advocacy of the rights of illiterate handicapped hero who suffers from hunch-back condition. He succeeds in his mission with endurance and the appreciative help offered by the heroine.

Let me present the lead players in the two movies.

Nadodi Mannan: hero: MGR (in double role), heroines: P. Bhanumathi (first), B. Saroja Devi (second), villains: two – P.S. Veerappa, M.N. Nambiar and M.G. Chakrapani – elder sibling of MGR, other players: M.N. Rajam, T.K. Balachandran, and G. Shakuntala, comedians: J.P. Chandrababu, T.P. Muthulakshmi, K.S. Angamuthu.

K.V. Mahadevan, Jayalalitha and MGR (circa 1969)

Adimai Penn: hero: MGR, heroine: Jayalalitha (double role), villains: S.A. Asokan, R.S. Manohar, other players: Pandari Bai, Rajshri, O.A.K. Thevar, comedians: J.P. Chandrababu, Cho Ramaswamy.

As one could see, MGR’s elder sibling Chakrapani played a notable role in the Nadodi Mannan. But, as he had retired, he was not a participant in the Adimai Penn movie. The only prominent name which appears in the above listing in both movies other than MGR, was that of comedian J.P. Chandrababu. Though conflicts had prevailed between MGR and Chandrababu in the 1960s due to erratic behavior (drug and alcohol use, debt and unpunctuality in settling call sheets and top of all, supreme ego) from the comedian, MGR did offer a helping hand to prop Chandrababu’s failing career. Sadly, Chandrababu failed to make the best use of the offered opportunity.

The number of songs featured in Adimai Penn was only 6, composed by four lyricists. Vaali wrote 3 songs, and the other three were equally shared by Alangudi Somu, Pulamai Pithan and Avinasi Mani. Two of the six songs, extolled the central theme of the movie – mother worship. T.M. Soundararajan sang the Alangudi Somu’s lyric, ‘Thai illamal Naan Illai’ [I won’t be here without my mother] for MGR’s character. Providing sex equality in extolling mother worship, Jayalalitha was offered a first opportunity to sing in her own voice, ‘Amma enral Anbu’ [Amma means love], lyric penned by Vaali. We should also note that even in the Nadodi Mannan, first heroine P. Bhanumathi (a singing star of repute in Indian movies) sang two very popular catchy tunes: a solo (Sammathama – Naan Ungal kooda vara sammathama? – Is it OK, if I join in your adventure?) and a duet with T.M. Soundararajan (Summa kidantha nilathai koththi sombalilamal er nadathi – Cleaning the barren land and using the plough with a challenge).

Another noticeable difference between the Nadodi Mannan and Adimai Penn movie was the singers who represented MGR’s voice. In the Nadodi Mannan movie, Soundararajan and Sirkali Govindarajan were the chosen singers. For the Adimai Penn movie, MGR introduced a 23 year old ‘new face’ from Telugu land, S.P. Balasubramanyam (b. 1946), to represent his voice apart from the regular Soundararajan. Whereas, Soundararajan was offered 3 solo songs, Balasubramanyam was given a duet song [Aayiram Nilave Vaa!] with P. Susheela. This became the big stepping stone for Balasubramanyam’s budding career as a playback singer in Tamil movies. There have been few circulating stories that MGR became disillusioned with Soundararajan’s attitude in late 1960s, and gradually came to side track him. Subsequently, MGR also offered opportunity to K.J. Jesudas, to represent his voice in 1970s.

The consensus opinion is that Balasubramanyam and Jesudas (both non-Tamils) are excellent singers with mellifluous voices. Nevertheless, for numerous MGR fans (including me), they simply couldn’t match the majestic bravura and range provided by three Tamilian singers – namely Soundararajan, Govindarajan and Chidambaram Jayaraman, whose voices matched splendidly with MGR’s inspirational songs of 1950s and 1960s. There was also another non-Tamil singer, A.M. Rajah (1929-1989), who had sung for MGR in a few 1950 movies. Like Balasubramanyam and Jesudas, Rajah’s voice failed to match MGR appropriately.

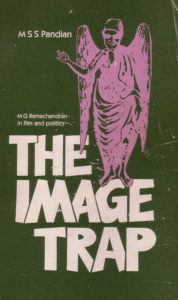

M.S.S. Pandian’s book, The Image Trap (1992)

Pandian’s ‘The Image Trap’ book cover

In my personal view, MGR scholarship had suffered a setback, due to the publication of Tamil Nadu social scientist Mathias Samuel Soundra Pandian’s lengthy essay ‘The Image Trap: M.G. Ramachandran in film and politics’, in a book form in 1992. It was a half-baked attempt by one, who hasn’t read widely on the development of cinema in other countries, including that of Soviet Union, China and Japan. The bibliography listed in this book includes 115 citations to works in Tamil and English. References to cinematic studies as well as biographies and autobiographies of individuals involved in movies and movie making were notably absent among these 115 reference citations! One can also understand Pandian’s bias on viewing MGR’s cinematic and political career from tinted Communist glasses (citations from Antonio Gramsci’s two published books in English translation and British historian Eric Hobsbawm’s two books attest to this fact.).

It is pitiable that Pandian while criticizing MGR and Nadodi Mannan movie for blatant propaganda with sentences like, “The DMK’s association with such propagandist films was not subtle and distanced; rather, it was blatant and articulate. When Nadodi Mannan, in which MGR starred, completed a successful 100 days run, the party organized a huge colourful procession in Madurai to celebrate the event…” had turned a blind eye to the Communist propaganda-linked movies in Soviet Union, China and also India from 1919 to the end of 20th century. Not that, movies produced in other countries, including Japan and Hollywood were devoid of other propagandist formulas. If this has been the trend world-wide, then why pick on MGR’s movies?

An excellent volume on World Cinema appeared in 1996 under the editorship of Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. In this reference source, 135 individuals were chosen for special features. And MGR was one among these 135. [see, part 1 of this series posted on Dec. 12, 2012, http://sangam.org/mgr-remembered-part-1/]. Another among the 135, was Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948). It appears that Pandian hasn’t known the name and works of Eisenstein. If he had seen Eisenstein’s 1925 classic movie The Battleship Potemkin (Bronenosets Potemkin), Pandian would have noticed the documentary footage of 1905 revolution inserted by Eisenstein in this movie. David Bordwell, who contributed the feature on Eisenstein to this World Cinema book had observed further:

“Throughout the silent era Eisenstein assumed that his aesthetic experimentation could be harmonized with the propaganda dictates of the State. Each of his silent films begins with an epigraph from Lenin, and each depicts a key moment in the myth of Bolshevik ascension…”

Another interesting essay that had appeared in this World Cinema book was that of Esther Yau, who had written on Chinese movies produced between 1949 and 1976, during the period Chairman Mao Zedong was the supreme leader. How Communist propaganda seeped into the movies produced in China is described vividly in this essay.

Numerous Chinese movies produced since 1949 can be mentioned to buttress the point of political propaganda in movies, to negate the erratic views of Pandian. Specifically, I mention one movie by the great Chinese actor-director Zheng Junli (1911-1969), which was produced before the 1949 Communist takeover, and later tampered to satisfy the sentiments of Communist hierarchy. This movie, ‘Crows and Sparrows’ (Wuya Yu Maque, 1949) is now considered as a classic, and noted as ‘One of the last fruits of a fertile period in the cinema of pre-revolutionary China’.

According to a description provided by Bergan and Karney for this film “At first, Junli’s first solo directorial effort was subject to censorship from the Nationalist Kuomintang government, but when the Communists came to power during post production, much of the cut dialogue was restored and more anti-KNT slogans were added with relish.”

It is unfortunate that Pandian (1959-2014) had a relatively short life and was even 5 years younger to me. Thus, I hesitate to criticize his work, as he is not among the living to defend his views. Nevertheless, his lengthy essay published in 1992 had formed the main reference source for non-Tamil scholars in India and elsewhere to rely on the movie and political career of MGR. Until he died, Pandian had failed to revise his work for its biased contents. Thus, to set the facts in order, I have to strongly criticize Pandian’s scholarship on MGR’s career.

Pandian’s Malice against that of Kannadasan and Cho’s Acclaim

Apart from interpretational flaw in the book, it also appears that Pandian had attempted to mask the reality by inserting sentences to attack MGR’s credentials as a man endowed with generosity. Here is one of Pandian’s finding:

“For our purpose, what is important is not so much whether MGR was really generous with his wealth (which he often was not), but how he was projected as a giver on the popular mind.” [Note by Sachi: the word in italics, is as in the original]

In translation, especially the five words within parenthesis reads that MGR was not a generous person, but he was “projected as a giver on the popular mind.” Even those who had criticized MGR publicly, and those who knew MGR personally and professionally (for instance, poet Kannadasan and satirist Cho Ramaswamy) had openly acknowledged MGR’s generosity to the needed public. MGR’s generosity to Tamil Tigers of Eelam became an international news in mid 1980s.

On MGR’s generosity to others, Cho Ramaswamy had described this: “Many knows well on the generosity of MGR. Some suggest reasons like ‘He does it for reducing his income tax, or for publicity’. Even if that’s so, we have to think how many amongst us have that sort of mind to be generous to others. Apart from this, MGR had helped numerous folks without any publicity. I have been told this by those who received such help. To aid someone at a needed time is a great thing. That MGR had done such things is an unquestionable truth. One actor had told me this. ‘If we set the coal in the furnace and stand in front of a house with a belief that we can have a meal, it should be only MGR’s. There aren’t anyone like him.’ How many will be offered such a sincere certificate like this?” Cho wrote this, 20 years after MGR’s death!

Poet Kannadasan had reminisced in his autobiography the helping generosity of MGR, even when both were not in talking terms! In the passage translated below, Kannadasan had identified himself in third person singular, which I indicate with ‘K’ in parenthesis:

“Even though he (K) had serious conflict with MGR, his generosity was so kind that MGR bought the share he (K) had in a movie, and gave him (K) a big amount. In those days, there wasn’t that much promotions and publicity. They were so quick in helping others. It’s because of that, he (K) was able to live without savings.”

Thus it’s difficult to fathom, why Pandian had to smear MGR’s generosity with such malice, by rejecting available evidence in hand? In another page, Pandian had written,

“In both real life and on the screen, MGR was presented as one among the common people and at the same time he was distinct from and stood above them. Perhaps we may mention here that this is very similar to the manner in which fascist propaganda projected Hitler;….” In this sentence, Pandian had failed to include the propaganda of other heroic figures from Communism, such as Lenin, Stalin and Mao, But notoriously, he had inserted Hitler’s name and fascist propaganda to smear MGR!

Movie making and Audience Angle

To prove that Pandian’s overall views on MGR’s movies are nothing but ludicrous fandangle of a Marxist critic, I provide below the thoughts of four well respected contemporaries of MGR, which are totally in sync with MGR’s ideas of movie making. Two great actors (Laurence Olivier and Marlon Brando) had noted what is acting in these words:

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989): “Never underestimate the audience, never patronize them, because, if you do, they will know. They are far more intelligent than you may think. They pay your bills and fill your stomach. Without them you are in an empty room again with a bare cupboard. You must always treat them with respect, be they one or a thousand.”

Marlon Brando (1924-2004): “In acting everything comes out of what you are or some aspect of who you are. [Note by Sachi: Words in italics, are as in the original.] Everything is a part of your experience. We all have a spectrum of emotions in us. It is a broad one, and it’s the actor’s job to reach into this assortment of emotions and experience the ones that are appropriate for his character and the story…I wanted to make pictures that were not only entertaining but had social value and gave me a sense that I was helping to improve the condition of the world.”

Two great directors (Charlie Chaplin and Akira Kurosawa) had expressed that biased critics don’t really know about the concept of movie making. Here are their exact words:

Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977): “I was depressed by the remark of a young critic who said that City Lights was very good, but that it verged on the sentimental, and that in my future films I should try to approximate realism. I found myself agreeing with him. Had I known what I do now, I could have told him that so-called realism is often artificial, phoney, prosaic and dull; and that it is not reality that matters in a film but what the imagination can make of it.”

Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998): “Critics may be affecting today’s audience negatively. They see films here [pointing to his head – Ed.]. No! I want to tell them to see films here [pointing to his heart – Ed.] because I make films thinking that way. I do not want them to try to reason everything. The people who pay to see films will see a film as it is. Furthermore, I do not believe that film is simplistic, but multifaceted…A film should appeal to sophisticated, profound-thinking people, while at the same time entertaining simplistic people. Even if a small circle of people enjoy a film, it will not do. A film should satisfy a wide range of people, all the people.”

Isn’t it true that the vision of MGR and his collaborators in Nadodi Mannan and Adimai Penn movies did satisfy the sentiments of his four illustrious contemporaries noted above? These movies still entertain and educate Tamil audience even though 60 and 49 years had passed since their original release.

Cited Sources

Ronald Bergan and Robyn Karney: Bloomsbury Foreign Film Guide, Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd., London, 1989, p. 133.

Marlon Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me, Century, London, 1994, pp. 245 and 416.

Charles Chaplin: My Autobiography, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1964, pp. 383-383.

Bert Cardullo (Ed): Akira Kurosawa Interviews, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2008, pp. 140-141.

Kavignar Kannadasan: Mana Vaasam (Autobiography, vol. 2), Vanathi Pathippagam, Chennai, 5th ed., 1991 (originally published, 1988), p. 141.

MGR: Naan Yean Piranthaen – Part 2 [Why I was Born?], chapter 111. Kannadhasan Pathippagam, Chennai, 2014, pp. 1243-1254.

Aranthai Narayanan: Thamiz Cinemavin Kathai, 3rd ed., New Century Book House, Chennai, 2008.

Laurence Olivier: On Acting, Sceptre-Hodder and Stoughton Paperbacks, London, 1986, p. 221.

Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen: Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema, new revised ed., Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1999.pp. 355 and 398.

Cho [Ramaswamy]: Athirstam Thantha Anupavankal (Experiences offered by the Luck), Alliance Company, Chennai, 3rd ed., 2008 (originally published, 2007), ch. 16, pp. 111-119.

Anon. K. Shankar dies. The Hindu (Chennai), Mar. 6, 2006.

Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (ed). The Oxford History of World Cinema, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996.

Thanks Dr. Sachi for the wealth of information about MGR, in particular the praise from Cho and Kannadasan regarding his generosity, I always thought that they were his critics only. The fact that MGR’s films withstood the test of time is explained by your referral to four well respected contemporaries of MGR.