Ascendancy in Tamil Nadu Politics

by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 30, 2022

MGR skimming the ‘Makkal Kural’ [People’s Voice] Newspaper (circa 1977)

“Part-64 which I found most informative, tying together the various strands of that period of the cinematic and the political in MGR’s career. Marudhakasi’s memoirs are skillfully employed to show MGR’s astuteness and evolution as a political leader. JP’s diary is consummately employed. An excellent compendium of the events of those two years. I learnt for the first time the date of the addition of All India to ADMK which I had tried to find unsuccessfully till now. Thank you.”

My response to Kannan’s comment, sent the following day was,

“As for the specific date of addition of prefix All India (AI), in front of ADMK, I guess, I picked up this information from the party website, which carried a column indicating notable dates in a history of the party. This was during the period when Jayalalitha was at helm. I haven’t checked the party website lately, and I don’t know whether that particular link still survives. I wanted to elaborate a little on that issue of party’s name change, but missed it inadvertently; because in his autobiography Karunanidhi had noted specifically about deciding not to change the DMK party name, during the Emergency period. Thus, subtly implying while he had self-respect, MGR was too pliant to Indira’s whims.”

Not changing the name of DMK to Indira’s whims

This is what Karunanidhi had written in chapter 76 of his autobiography (vol. 2):

“…One day there was a news that Indira government was about to ban regional parties. Following this, all of you know what happened. MGR changed his party’s name from Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (ADMK) to All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK).

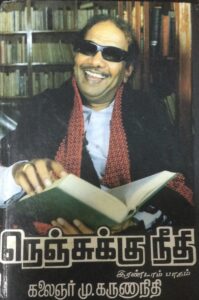

Karunanidhi’s Autobiography, vol. 2

Senior leaders of DMK also expressed the view that it’s safe to change the DMK name. A few in the Cabinet also agreed to this; (A suggested view was) to announce that DMK is not a political party, but a cultural organization. Only professor (K. Anbhazhagan) supported my view that in haste, we shouldn’t lose our fundamentals. I said, Kazhagam devotee would die if he hears that this sort of thinking prevails at the top level, In between, this news had spread to those who were held in Chennai prison under MISA act. The top rankers there had sent a letter to us ‘For whatever reason, there should not be any change in the name of Kazhagam or the leadership.’ I read this letter to those who were in agitated mood and pledged emotionally ‘Lets live with Kazhagam name, or lets fall with Kazhagam name’. Since then, the debate relating to changing either the Kazhagam name or the leadership of Kazhagam subsided. But, here and there, there some grumbling persisted.”

MISA, mentioned by Karunanidhi above, stands for Maintenance of Internal Security Act. Around that time, it was considered a badge of honor among DMK party members to be held as a MISA convict, and survive hardship. M.K. Stalin (son of Karunanidhi), the current chief minister of Tamil Nadu, was a MISA convict.]. According to Karunanidhi, on the day following the dismissal of his government on January 31, 1976, 25,000 DMK party activists were detained in Tamil Nadu prisons. Especially, those politicians [irrespective of party affiliations – DMK, DK, Communist Party (Marxist) Congress (Old)] were physically ill-treated and tortured in Chennai prisons. He also had mentioned, DK’s general secretary K. Veeramany, and DK activist actor M.R. Radha were also held in detention as MISA detenus.

Karunanidhi’s citation of 25,000 party activists detained is an exaggeration. Inder Malhotra’s biography on Indira Gandhi provides a following contradictory detail of detentions during the Emergency period. “According to Amnesty International, 140,000 Indians were detained without trial in 1975-6…for the Janata government, after it came to power, computed, on the basis of information received from the states, that the detainees numbered 100,000…” And Tamil Nadu was one of the least affected states by the Emergency. It’s inappropriate to guess, by population count, that one quarter of the detainees during Emergency were in the Tamil Nadu state. Malhotra also mentions that 22 Emergency period detainees died in jail. One prominent figure among these 22 was Chockalinga Chitti Babu (1935-1977), DMK’s sitting Lok Sabha MP for Chengalpattu constituency, who died on January 4th 1977. Though the Emergency period, officially came to an end on March 21, 1977, after Indira Gandhi’s defeat in the March general elections, Karunanidhi had stated that following Indira’s January 18th announcement that the twice postponed general elections will be held in March 1977, between January 23rd and February 2nd, all the DMK detenus were released.

Indira’s Eyes on Eelam Tamil Issue

When did Indira Gandhi publicly turned her eyes to the perennial issue faced by Eelam Tamils? This question had been raised in the past. Karunanidhi had provided a clue. He mentions that, on February 15, 1976, when Indira visited Chennai, to formally link the two ‘Congress parties of Tamil Nadu’ (that of Kamaraj’s Old Congress and her Indira Congress) made a speech at Chennai beach.

“ ‘ Those belonging to the DMK make false propaganda on Ilankai Tamils. We shouldn’t allow this to happen. Because of this, Karunanidhi is the reason for faltering of the goodwill between the Indian and Sri Lankan government.’ This was madam Indira’s speech at the sea beach.

This is an example that Indira Gandhi was somewhat scared about the firm stand DMK held on the issue of Ilankai Tamils.”

As he had recorded, to be fair, Karunanidhi’s stand on the Eelam issue was highly appreciated by Eelam Tamils up to 1976. But, since 1980s, he faltered badly (see below). What was MGR’s stand on the political issue of Eelam Tamils then? At that time, his thinking was that of a movie star (see below, Kannadasan’s view on MGR). It was reported that to a question by a cine reporter, he had flippantly answered, ‘Apart from Tamil fans, I also have Sinhalese movie fans in Ceylon.’ His answer was true indeed. This comment was played up in Sri Lanka by Karunanidhi’s supporters that MGR was a klutz (an inept blockhead) when it comes to helping the Tamils in Sri Lanka.

To be fair by MGR, two points have to be noted here. First, MGR was a quick study in politics, and he did learn the problems of Eelam Tamils, most probably after the 1977 anti-Tamil riots in Sri Lanka, immediately after he became the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. Secondly, at that time the recognized Eelam Tamil leader was Amirthalingam, who had maintained a congenial relationship with Karunanidhi. Among the Federal Party leaders at that time, only Chelliah Rajadurai (MP for Batticaloa) had links with the Tamil movie industry giants like Kannadasan and MGR. Amirthalingam’s partiality to Karunanidhi might have negated MGR’s interest on Eelam Tamils. And, there was a ‘cold war’ brewing between Amirthalingam and Rajadurai.

Indira Gandhi biography (1989) by Inder Malhotra

One Important development during the Emergency Period (1975-1976)

One important development which occurred during the Emergency Period, which would have serious repercussions in Tamil Nadu-Sri Lankan politics and the budding Eelam Tamil militant movements for decades was the Centralization of Intelligence Agencies in India, by Indira. What Myron Wiener wrote about this in 1976, is reproduced below:

“…the most important are the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), organized directly under the Prime Minister’s secretariat, and the Central Bureau of Investigation (the CBI), located in the Home Ministry. The decision to declare an emergency would hardly have been possible had Mrs. Gandhi not strengthened and centralized India’s intelligence organizations. It is widely believed in India that RAW has built up dossiers on government opponents, on critics within the governing Congress party, journalists, businessmen and bureaucrats. The intelligence provided by RAW made it possible to arrest thousands of opponents on the night of June 26th [1975], to dismiss or induce the early retirement of many civil servants, and to keep a watchful eye on India’s growing underground.”

Later it will be described, how MGR could use his common sense approach to tackle and override the dictates of these RAW officials in Chennai and New Delhi on Eelam Tamil militants in mid 1980s, while his predecessor (Karunanidhi) and successor (Jayalalitha) simply danced like puppets to the ‘in the LTTE hit-list’ tunes set by the RAW officials during 1990s.

Communists in Tamil Nadu and their affiliations with DMK and ADMK

M. Kalyanasundaram

When MGR established his party fifty years ago, Mohan Ram observed, ‘the Indian communist movement is now fragmented.’ There were (a) two non-Maoist parties: pro-Moscow Communist Party of India (CPI), founded in 1925, and Communist Party of India – Marxist (CPI-M), founded in 1964, (b) a Maoist Communist Party of India – Marxist Leninist (CPI-ML), and (c) several Maoist groups, majority of them called ‘Naxalites’. In addition, there was even a Tamil Nadu Communist Party, founded in 1973 by Manali Kandasamy, few months after the establishment of MGR’s party. Since independence, unlike in West Bengal and Kerala states, none of the Communist Parties never gained mass support in Tamil Nadu to have a ruling influence. Multiple factors played a role in this outcome. Primarily, in Indian societies culturally imbued with millennial years of piety inbred in literature, music and drama, atheism (rejection of God) is a tough sell. Secondly, those who became notable Communist leaders, gained recognition not necessarily for their political skills but for their talents in oratory, literature, and poetry. Social reformer P. Jeevanandam (107-19963), folklorist N Vanamamalai (1917-1980), K. Balathandayutham (1918-1973), poet Pattukottai Kalyananasundaram (1930-1959) and novelist D. Jayakanthan (1934-2015) were prime examples. Thirdly, with vigorous activities in cinema linked to Tamil nationalism, DMK had hijacked the atheism votes, because the Communist Party’s plank of pan-globalism or pan-Indianism was far fetching to illiterate masses, even in caste-ridden milieu. A popular derision among Tamils about the local Communists in those days were, ‘When it rains in Moscow, these guys open their umbrellas here.’

Since DMK became the ruling party in Tamil Nadu in 1967, either the CPI or it’s 1964 offshoot – CPI-M hitched themselves with DMK bandwagon for crumbs of electoral seat allocations by DMK. After MGR’s exit from the DMK in October 1972, Padmanabhan summarized the DMK-CPI relationship in the following terms:

“The agitation by the CPI to demand the fixation of ceiling on land holdings at 15 standard acres per family and not per individual, the defying of the police ban on meetings by Kalyanasundaram and K.T. Raju, CPI’s refusal to support DMK candidates in the (Legislative) Council and Rajya Sabha elections, and above all the CPI’s new relationship with the newly formed ADMK enraged the DMK leadership. For the CPI, the DMK’s unilateral decision to snap ties with Congress (R) was a principal issue. It declared that the concept of autonomy, as advocated by DMK, had mischievous potential of mortgaging Tamil Nadu to foreign monopolists in the holy name of industrial development. Finally, when CPI submitted a memorandum to the Prime Minister alleging several corrupt practices on various issues by DMK, the alliance crumbled beyond any retrieving.

The CPI(M) was hesitant to support M.G. Ramachandran, who founded ADMK because of his personal clash with Karunanidhi. But CPI went ahead with its decision by supporting Ramachandran and a new alliance between ADMK, Congress (R) and CPI began to take shape. But, DMK opposed it vehemently, along with the CPI (M).”

MGR associated actively with M. Kalyanasundaram (1909-1988, Tamil Nadu leader of CPI), an elected MLA from 1952 to 1967, and subsequently an MP from 1967. What could have been the circumstances for Kalyanasundaram aligning with MGR? It could be inferred that MGR needed a senior politician nearby who could guide him in the corridors of power in Lok Sabha, and Kalyanasundaram, a career politician, came in handy. Reversely, Kalyanasundaram also might have wished to make hay using the popular appeal of MGR. But, in two years (by October 1974), ADMK-CPI relationship had soured.

As reported by Mohit Sen, “sections of the ADMK had launched on rather virulent polemics against the CPI – ostensibly because of the latter’s criticism of Annaism. But the real reason was evidently that the CPI had decided upon independent mass action on certain major issues facing the people; such action involved not only sharp criticism of the DMK but also of the all-India Congress. The CPI also made it quite clear that not only was it politically quite independent of the ADMK but that it was sharply demarcated from it ideologically. The sharp reaction of the CPI leadership to outbursts on the part of the ADMK as well as its persistence in independent mass actions finally led the latter to somewhat moderate its tone and stress, again, the need and possibility of unity between the two parties.”

ADMK’s ascend as the leading Opposition party in 1976

A synopsis of party ranks at the Tamil Nadu Legislative assembly, between 1971 and 1976, were as follows:

- The party position on May 1, 1971 (after the General election): DMK 182, Congress (Old – Kamaraj Party) 15, Communist Party of India (CPI) 8, Praja Socialist Party 4.

- Prior to MGR’s eviction from DMK, on Aug 1, 1972: DMK 183, Congress (Old-Kamaraj Party) 13, Communist Party of India (CPI) 8, Congress (Indira Party) 6.

How come Congress (Indira Party) had 6 MLAs? The 4 who were elected under Praja Socialist Party ticket in 1971, and 2 from Congress (Old-Kamaraj Party) joined together to form Congress (Indira Party).

(3)After the formation of MGR’s ADMK, on Apr 2, 1973: DMK 174, Congress (Old – Kamaraj Party) 12, ADMK 11, CPI 8, Congress (Indira Party) 6.

- When the DMK government was dissolved, on Jan 31, 1976: DMK 167, ADMK 16, Congress (Old – Kamaraj Party) 13, Congress (Indira Party) 7, CPI 5, Thazhthapattor Munnetra Kazhagam of Satyavani Muthu 2.

Between 1973 and Jan 1976, MGR’s breakaway party attracted 5 more MLAs from DMK, to become the lead Opposition party in Tamil Nadu. Ms Satyavani Muthu (1923-1999), a prominent woman leader of DMK also left the party to form her own breakaway party Thazthapattor Munnetra Kazhagam. She was one of the original 15 MLAs elected on DMK ticket in 1957 Madras Assembly elections. Subsequently, she would merge her party with MGR’s ADMK in 1977.

Though numerically, ADMK of MGR became the leading Opposition party, in the Tamil Nadu legislative Assembly, he did not assume the responsible Leader of Opposition role. Did MGR actively participate in the Tamil Nadu assembly sessions, between 1971 and Jan 1976? A check at the statistics provided in the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly Quinquennial Review 1971-76, indicate that he was NOT an active participant, after he formed his breakaway party. In the composition of Business Advisory Committee 1973-74 (which was constituted on March 31, 1973), MGR’s name is listed among 15 members of the Assembly, that included 4 Cabinet ministers – M. Karunanidhi, V.R. Nedunchezhiyan, K. Anbazhagan and S. Madavan, in addition to deputy speaker P. Seenivasan who functioned as the chairman of the committee, in the absence of the Speaker (the position being vacant). But, MGR’s name is missing in the list of 1974-75 (constituted on April 9, 1974) among 17 members of the Assembly, and also in the list of 1975-76 (constituted on April 19, 1975) among 17 members of the Assembly. In addition, he was not (1) among the members who made higher number of speeches, and (2) among the members who spoke for higher number of hours in either Tamil or in English.

It could be inferred that MGR’s strategy was to convince the public of a need for change in administration via what he had done best – propaganda via movies and songs. MGR might have thought that it was a waste of time in participating at the Legislative Assembly sessions, addressing 235 members, majority of whom didn’t identify with his political challenge.

As he was elected as Chief Minister three times consecutively (1977, 1980 and 1984) and died in harness, MGR never experienced the Leader of the Opposition role in the Tamil Nadu politics.

Deflecting the ‘merger feelers’ with the Congress (Indira) Party

In chapter 61 [https://sangam.org/mgr-remembered-part-61/], I had alluded to this vital issue of Indira Gandhi’s merger feelers to MGR. This also could be an important reason, for MGR in not focusing his time as an elected legislator in the Tamil Nadu assembly. He opted to spend much his time in cinema activities. He was forced to play his cards on this party merger issue tactfully: supporting Indira Gandhi’s Emergency policy on one hand, while not taking seriously the call from Indira’s handlers to merge his newly formed party with that of Indira’s Congress Party. As a quick study, MGR was probably aware of the plight faced by E.V.K. Sampath, who left Anna-led DMK in 1961 to form the Tamil Thesiya Katchi (Tamil National Party), only to merge his breakaway party with the Congress. But unlike Sampath’s situation, for his survival in the battle with Karunanidhi, ‘Anna’ was MGR’s breath. If he had opted to merge his fledgling party with that of Congress (Indira), what could happen for his ‘Anna passion’? All of his past ‘Anna propaganda’ in the movies and songs, would vanish in thin air?

Comedian and political analyst Cho Ramaswamy had recorded in one chapter of his memoirs, how MGR was peeved by his reporting of the ADMK merger talks, published in his weekly Thuglak magazine. This relates to a conversation he had with T.S. Durairaj (1910-1986), a popular Tamil cinema comedian of 1940s and 1950s. What Cho had written, I provide English excerpts below:

Tamil cinema comedian T.S. Durairaj (in a 1955 movie grab of a song sequence)

“One day, while we were talking, Durairaj told me that he knew all the politicians. This was the beginning of MGR’s anger on me. Because, after many days, I heard a story. Congress (Indira) Party MLAs from Karnataka and actor Durairaj had met with MGR and there was some significance in it. When inquired further, there was also a suspicious detail. One of the astrologers in Indira Gandhi’s circle, a Sundaram, was an in law of Durairaj was that. As it became interesting, I contracted Durairaj and inquired, and also talked with him on phone. ‘Thambi…why we had to visit MGR? It’s politics. He will be joining Congress. I’m the one who will handle this. Madam Indira passed message through my in law. That’s why all this arrangement. Karnataka MLA Gundu Rao, then one ‘Khan’ – we all went to MGR and talked. As he mentioned that he was willing to be interviewed, we sent a reporter. Durairaj had talked to them in detail about what MGR discussed with the MLAs of Congress Party, and the merger talk.

When that particular issue of Thuglak was released, MGR became angry. Then, a rebuttal of MGR to this item appeared in the official ADMK paper Thennagam. Then, I called the then Karnataka MLA Gundu Rao and asked. He confirmed what Durairaj had said. Furthermore, Gundu Rao also added, MGR had told ‘If an inquiry commission is appointed on Karunanidhi, I’m prepared to merge my party with Congress (party).’ I talked again with Durairaj. As he was somewhat saddened by MGR’s anger, he requested to be released from this controversy. But, I was not willing. As such, he did confirm the details.

MGR had expected that his discussions with Congress (Indira) Party messengers would remain a secret. But, as opposed to this, due to my act, his anger on me couldn’t be dismissed so simply. But, one thing. My acts did cause him discomfort at that time, but he didn’t worry that much for long. Within few days, he had forgotten and our friendship did continue.”

Unfortunately, Cho had omitted the ‘date’ [or ‘year’] of Thuglak issue where he had published this wooing episode of MGR by Indira’s agents from Karnataka, via one of her astrologers (an in-law of comedian actor T.S. Durairaj). My guess is, this should have been after the untimely death of Indira’s confidant Mohan Kumaramangalam in May 1973 and before the declaration of Emergency in June 1975. Let’s clarify the related dates. The allegation of corruption in the DMK party was submitted by MGR and the CPI to the Central Government in November 1972. But, a Supreme Court judge Ranjit Singh Sarkaria was appointed to investigate the allegations of MGR and Kalyanasundaram only in Feb 3, 1976, after the dismissal of Karunanidhi government in the Tamil Nadu. For reasons known only to Indira Gandhi, this delay in appointing the commission turned out in favor of MGR; because following the death of Kamaraj, he was able to consolidate the mantle of a viable Opposition leader position in the state and simultaneously deflect or ignore the ‘merger feelers’ from the Congress Party folks. The chosen leader of the merged Congress Party (Indira’s Congress and the Old Congress led by Kamaraj) in Tamil Nadu, G. Karuppaiah Moopanar, in Feb 15, 1976, was no match to MGR in mass appeal. In addition, even among the long standing Congress Party members (such as Sivaji Ganesan and Kannadasan), there was resentment to G.K. Moopanar’s selection by Indira.

Also, I can infer it was to MGR’s advantage that no ‘political heavy weight’ (older than MGR) either in Tamil Nadu or in Karnataka was deployed in this ‘party merger’ talks by the Indira’s side. Though R. Kundu Rao became the Chief Minister of Karnataka subsequently, from 1980 to 1983, during the pertinent period in the first half of 1970s, he was simply a rookie MLA from Karnataka in his late 30s and a crony of Sanjai Gandhi, angling for the political munificence of Indira Gandhi. Thus, MGR was able to side step this ‘party merger hook’ thrown at him.

Poet Kannadasan’s angle on MGR and Karunanidhi

As one who had seen both MGR and Karunanidhi in proximity for decades, poet Kannadasan’s (who himself left the DMK with E.V.K. Sampath) views deserves recognition. On MGR’s interest, Kannadasan had recorded the following: ‘I know very well that MGR never thought that he would lead a new party and wished to become a political leader. He would only think that, he shouldn’t leave his grip in the cinema field. He never wished to spend his time as a full time politician. BUT, the credit to pull MGR into politics valiantly and make him as a political leader should go to Karunanidhi. By throwing out MGR from the party and losing substantial supporters of the party also should go to Karunanidhi.’

‘For a long time, MGR and I had a work relationship. In this, though there was sour taste, it had sweetness as well. Even, I was surprised by his behavior and credibility of his deeds. I came to realize, why I was not blessed with such functional energy.’

Simultaneously, Kannadasan’s take on Karunanidhi was: ‘Since 1971, Karunanidhi’s path took a distinct direction. He began to believe that circumstances had made a situation that none in Tamil Nadu could challenge what he can do. ‘Regional autonomy’ was a slogan, which was originally raised by Ma. Po. Si (aka, Mayilai Ponnusami Sivagnanam, 1906-1995). He had grabbed this and revised it to a ‘Separation plank’. His devotees started equating to Karunanidhi to Mujibur Rahman and other freedom fighters. If you ask me to what extreme this ‘show’ progressed, [I say] there was this poet’s colloquium. In it, one [guy] belonging to the DMK made this offering criticizing Hindi. He used the word play ‘(H)Indi Rani – Dasi’ (Hindi queen – prostitute) to ‘Indira – Ni – Dasi’ (Indira – You – prostitute). It had gone to such obscenity. Indira Gandhi had to tolerate this; also the Congress folks here. These details had been reaching Indira’s ears, regularly.”

*****

Cited Sources

Cho [Ramaswamy]. Athirshtam thanta Anupavangal [Experiences offered by the Luck], Allianace Co., Chennai, 3rd ed., 2008 (1st published 2007), pp. 235-239]

Forrester D. Factions and film stars: Tamil Nadu politics since 1971. Asian Survey, 1976; 16(3): 283-296.

Kannan: MGR – A Life, Penguin Books, Gurgaon, Haryana, 2017, pp. 208-222.

Kannadasan: Naan Partha Arasiyal [The Politics I had Seen], Kannadhasan Pathippagam, Chennai, 13th ed., 2012 (originally published in 1978), pp. 96-102.

Karunanidhi M. Nenjukku Neethi, vol. 2, chapters 73-81, Thirumagal Nilayam, Chennai, 1985, pp. 532-586.

Malhotra I. Indira Gandhi – a personal and political biography, Coronet Books – Hodder and Stoughton, Sevenoaks, Kent, 1989, p. 178.

Mohan Ram. The Communist movement in India. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, winter 1972; 4(1): 30-44.

Padmanabhan VK. Communist Parties in Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Political Science, 1987; 48(2): 225-250.

Palmer ND. India in 1976: The politics of depolticization. Asian Survey, 1977; 17(2): 160-180.

Sarkaria Commission: Karunanidhi partially guilty. India Today, April 15, 1977. https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/indiascope/story/19770415-sarkaria-commission-karunanidhi-partially-guilty-823648-2014-08-04

Sen M. Twists in Tamil Nadu. Economic and Political Weekly, Nov 2, 1974, 9(44): 1845-1846.

Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly Quinquennial Review 1971-76, published by the Govt of Tamil Nadu, 1977. G.M. Alagarswamy, Secretary, Legislative Assembly, dated July 13, 1976, 326 pp.

Wiener M. India’s new political institutions. Asian Survey, Sept 1976; 16(9): 898-901.

One more informative episode on MGR by Dr. Sachi, even though I followed the news events of that era closely, one information was new to me which is about MGR’s commitment to Eelam issue. I thought he was committed right from the beginning, but it is interesting to know the transition from ignorant perspective to lead player.

Regarding his not assuming the role of opposition leader, I think he is inherently the hero! I remember that during one interview where he was asked about not attending the house, he said the assembly is dead!

I do acknowledge the point made by Arul, relating to MGR’s, unwillingness to play the Leader of the Opposition. I infer, that by upbringing and character, with the exception of his two family members (his mother and elder brother Chakrapani), and later probably Anna, MGR never played second fiddle to anyone, since 1950.

Quoting Inder Malhotra on the number of people arrested from Tamil Nadu during emergency is questionable. The maximum number of people arrested during emergency are from opposition ruled states and at that point of time TN was a one among the few states ruled by oppositionto the central govt.