by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 9, 2016

Boxing champion Muhammad Ali meant different things to different people – to Americans and non-Americans, to Blacks and non-Blacks, to sportsmen and non-sportsmen, to journalists and non-journalists, to Muslims and non-Muslims, to Vietnam war participants and Vietnam war opponents. There are no boxing champions among the Tamils. But, millions of Tamils do adore Muhammad Ali for his activism against racism and equal rights, as well as for standing up to the edicts of Uncle Sam.

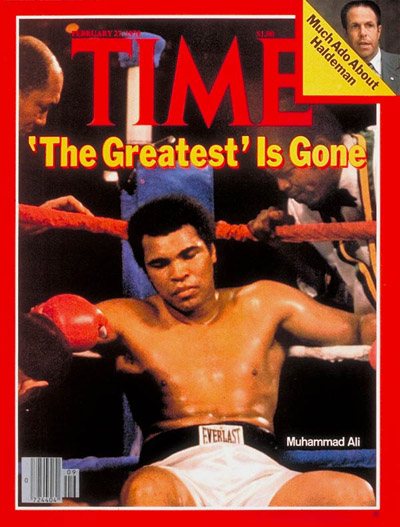

Here, I write what Ali’s activism meant to a Tamil boy (who was 11 years younger to him), who was growing up in Colombo, Ceylon. In 1960s and 1970s, there were no TV channels、Cable pay per view or CNN. The news about the Vietnam War trickled via radio news; in local newspapers, under the ‘International News’ pages and via the syndicated columns of American journalists, including humorists like Art Buchwald. For one who was hungry about news (especially sports and movies) from America, I used to visit the USIS Library in Colombo to skim through the pages of Time, Newsweek and Sports Illustrated magazines.

Excerpts from My Autobiography (2004)

Excerpts from My Autobiography (2004)

This is what I reminisced about what Ali’s activities meant to me, in my autobiography Tears and Cheers (vol. 1), published 12 years ago.

“If there was one role model whom I liked for instilling in me the worth of standing up to one’s own values and succeeding against serious odds, it was boxing champion Muhammad Ali. Since he won the heavyweight championship title from Sonny Liston as Cassius Clay on February 25, 1964, he became my idol and I followed his progress in the boxing ring and larger social arena avidly. I grew up with Ali’s professional career, for the next 17 years, until he lost his final fight on December 11, 1981 to Trevor Berbick. By then, I had reached America and was a graduate student at the University of Illinois. The Beatles also burst into the popular scene simultaneously in 1964, and there were a couple of my class mates who were crazy on the Beatles and their melodies. But, I preferred Muhammad Ali’s rhyming verses better than the songs of the Beatles.” (p. 27).

Again, after Ali’s first defeat in the ring to Joe Frazier, my thoughts were as follows. “I remember the end of the first week of March 1971. The news from New York that my sports idol Muhammad Ali had lost for the first time in his inimitable career to Joe Frazier shocked me. I was sullen for a few days. My school days were coming to an end. I grew up with Ali’s heroics since 1964, and I was no exception to any boy growing up anywhere in the world of that era. How many hours I would have spent ‘analyzing’ with my friends about how Ali punched Liston, Patterson, Terrell, Bugner, Williams and the likes? He was unbeaten until then. I liked Ali’s self confidence, showmanship, political activism and courage for standing up to his beliefs. Of course, I liked his poetry too. I was mesmerized by his poetic logic.

I don’t have to be – what you want me to be.

I’m free to be – what I want.

That’s the spirit of freedom, with touching cadence and spicy message. It was a gem for a Tamil teenager! None of the sportsmen until then or even hence could stir the emotions with poetry like Ali. That’s why he still remains as my hero.” (p. 41)

Views of my American mentor Prof. John Erdman Jr.

Views of my American mentor Prof. John Erdman Jr.

After I heard the death of Muhammad Ali, I sent the following mail to my mentor John W. Erdman Jr. (b. 1945) at the University of Illinois. He was a Vietnam War veteran.

“Dr. JWE,

Now that Muhammad Ali is not among the living, I have never spoken to you about his stand on the Vietnam War. He remains my one and only sports idol since 1964. As a Vietnam War vet, what were your reactions then, when you were in the Vietnam fields, and in hindsight, what is your reaction now.

I remember the day, when you took me to Dayton, to attend Sandy’s wedding, and I was asking some questions about your Vietnam experiences. But, I don’t think I had asked you this question. Best regards.

Sri”

The very next day, I did receive Prof. Erdman’s reply and he had given me permission to open it to Sangam site readers.

“Sri,

Thanks for asking. At the time, many people were opting out of the Vietnam war. Many guys went to Canada, for example. My own mother suggested that I consider going to Canada which I never gave any serious consideration. I signed up for ROTC and was going to serve where sent. The war was not popular. I don’t recall being particular annoyed with Ali, instead feeling that he had a right to his religious and personal views. He paid dearly for this decision – almost 4 years banned from boxing, loss of his title and loss from grace.

Today, looking back, many of us feel that he was mostly a man of peace (except in the ring) and his refusal to serve was within his overall philosophy, not just avoiding Vietnam. For the last few days he has being honored throughout the USA for his views, his image and things he stood for. Rightly so. Of course he had 4 wives and numerous other relationships. Bottom line was that he was a great man.

John”

Thoughts of Ali and Frazier

I need to write something fresh, which have not been tackled by other eulogists of Ali. So, I make few observations on the autobiographies of Ali and that of his eminent rival in the boxing ring, Joe Frazier (1944- 2011).

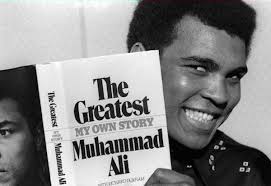

Ali’s autobiography, ‘The Greatest: My Own Story’ was published in 1975, when Ali was 33. It was ghost written by Richard Durham. It had 22 chapters, with the final one ‘Manila: September 30, 1975’ tagged in at the end, after the ‘Thrilla in Manila’ third fight with Frazier. Here are Ali’s words about this epic boxing fight, in the pre-penultimate paragraph of the book.

Ali’s autobiography, ‘The Greatest: My Own Story’ was published in 1975, when Ali was 33. It was ghost written by Richard Durham. It had 22 chapters, with the final one ‘Manila: September 30, 1975’ tagged in at the end, after the ‘Thrilla in Manila’ third fight with Frazier. Here are Ali’s words about this epic boxing fight, in the pre-penultimate paragraph of the book.

”The hardest fight I’ve ever had in my life – the deadliest and the most vicious. About how for the third time Joe Frazier surprises me with his stamina, his relentlessness and the gunpowder in his blows. How I open his lip and close his eye but he still keeps coming, forcing me into the ropes, making me deliver power when I don’t even know if it’s still there. How this time the butterfly has to stop floating so the bee can sting. Because it’s the same old Joe. The same Joe who dropped me in Madison Square Garden four years ago; who shook me in January 1974, round after round, before I could take him out.”

The penultimate paragraph paid tribute to Frazier’s skill again. “Should I say that the fight we had tonight is the next thing to death? That I felt like fainting and throwing up? Frazier is a helluva fighter and when Carlos Padilla, the referee, looks at Joe’s face, and his manager, Eddie Futch, won’t let him out of his corner for the fifteenth round, I’m so relieved, so tired, and in so much pain that my knees buckle and I stretch out right where I am – right there in the middle of the ring. Laying there, drained, I hear the blood pounding in my ears, and in the middle of the pounding, Joe’s words come back to me: ‘you one bad nigger. We both bad niggers. We don’t do no crawlin’.’ ”

In the penultimate chapter, entitled ‘Bomaye’ which described Ali’s surprising knock out win against George Foreman on October 30, 1974 in Zaire, Ali offered two advices for those who lose a fight.

First: “Only a man who knows what is to be defeated can reach down to the bottom of his soul and come up with the extra ounce of power it takes to win when the match is even.”

Second: “Too many victories weaken you. That the defeated can rise up stronger than the victor.”

For those (There are thousands!) who falter Ali for ill-treating Frazier with trash talk, I offer this snippet from Ali’s autobiography. What is most interesting for me (and probably other boxing fans) was the lengthy Ali-Frazier dialogue and banter they had taped in August 1970, on their road trip to New York, prior to the ‘Fight of the Century’ on March 8, 1971. There, (1) Ali introduces a poem he had written about the forthcoming fight to Frazier’s face. (2) Frazier acknowledges his debt to Ali, that the latter was his inspiration. Here are excerpts:

“Ali: Naw, man. I wrote a poem on you. Went like this.:

Joe’s gonna come out smokin’,

And I ain’t gonna be jokin’

I’ll be peckin’ and pokin’,

Pourin’ water on his smokin’

This might shock and amaze ya,

But I’ll retire Joe Frazier!

Frazier: (after pause) Yeah? Smoke still smokin’. It’s still smokin’. (Both laugh) I had my eye on you a long time. Remember when I used to call you up when you were about to fight Liston for the first time? You’d say, ‘Come on. Keep training. I’m gonna help make you rich,’ and stuff like that. I listened to it, you know. Thought about it. By talking to you on the telephone – you know, you wouldn’t let me get a word in edgewise – I made myself a promise. I said, ‘I’m gonna fight on; I’m gonna train on, and one of these days I’m gonna straighten him out!’

Ali: Look, I’m a little too experienced for you, Joe.

Frazier: I admit, you some kind of inspiration for me, more’n anybody I ever come in contact with. Every time I see you running off at the mouth, you know what I said? I just said to myself, ‘Well, Joe, look. This guy can back up what he says. You gotta do just a little more.’ When I go on the road, I run a little harder. ‘Cause I know I anna be able to meet you one of these days. You know what mean? I’d tell myself, the only way I know I can meet Cassius Clay is to keep winning, and keep knocking these cats out, you know? I had to get to you. Now here I am. They should allow you to fight, you know what I mean? Taking your license away like they did wasn’t justice. Fighting was your way of making a living for the family, like me. With a family like yours, you know, you gotta have enough to support them right. Believe what you wanna believe in. I’m a hundred percent with you on that. You got a whole lot of people out there believe worse than you. If they give you a license, I’d fight you anytime, anyplace. But I’d prefer it should be here in the United States.”

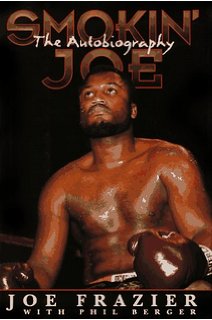

Joe Frazier’s autobiography ‘Smokin’ Joe – The Autobiography of a Heaviweight Champion of the World’ was published in 1996, when Frazier was 52. It was ghost-written by Phil Berger, and contained 10 chapters. In my reading, this book appears as a grudge book on Ali. There is no doubt that Ali had insulted Frazier with his loud mouth remarks. Thus, Frazier wanted to sock it back to Ali, 20 years after their rivalry in the ring had passed. Repeatedly, Frazier calls Ali by his birth name Clay, in his book. This is how, Frazier ends his book:

Joe Frazier’s autobiography ‘Smokin’ Joe – The Autobiography of a Heaviweight Champion of the World’ was published in 1996, when Frazier was 52. It was ghost-written by Phil Berger, and contained 10 chapters. In my reading, this book appears as a grudge book on Ali. There is no doubt that Ali had insulted Frazier with his loud mouth remarks. Thus, Frazier wanted to sock it back to Ali, 20 years after their rivalry in the ring had passed. Repeatedly, Frazier calls Ali by his birth name Clay, in his book. This is how, Frazier ends his book:

“It’d be easy for me to fall in line and act as if Clay was some fuzzy ole saint to me, like he is to so many others. I know that’s what people would like to hear. Forgive and forget.

But I’d be shuckin’ you if I told you that.

Truth is, I’d like to rumble with that sucker again – beat him up piece by piece and mail him back to Jesus. No, I ain’t forgiven him for what he said and did. I stood up for him when few others did. Told the boxing officials, ‘Let the man fight.’ Then, when he got what he needed, he turned on me and said everything bad that he could. Called me the white man’s champion to get the black men to turn on me. Called me a Tom and an ignoramus to demean me in public.

Now people ask me if I feel bad for him, now that things aren’t going so well for him. Nope. I don’t. Fact is, I don’t give a damn. They want me to love him, but I’ll open up the graveyard and bury his ass when the Lord chooses to take him. You see what the Lord did to him: He shut him down, that ungrateful scamboogah. Clay always mocked me – like I was the dummy. Getting’ hit in the head. Now look at him: He can hardly talk and he’s still out there trying to make noise.

People don’t understand this guy, don’t understand what he’s all about. Well, I’ll tell you: He’s about himself more than anything. Yeah, Clay – he was so busy being THEE greatest, he couldn’t see the snakes that were holding up his pants. Well, all that talk of his don’t amount to much anymore. He’s a ghost, and I’m still here.”

Many can comprehend the hurt feelings of Frazier. But, in his rage against Ali, Frazier himself has been un-Christian in his act. For his trash talk about ‘Open up the graveyard and bury his ass’, Grim Reaper made sure that Frazier will go first in 2011, before Ali! Frazier had also forgotten, that it was Ali who gave prominence and elevated Frazier as his near-equal. By winning against an un-defeated Ali (who had lost more than 3 years of his prime period as a boxer, due to Uncle Sam’s edict) in 1971, Frazier received prominent notice. Frazier’s notable superlative rivals in the ring were only Ali and George Foreman. Frazier’s four losses of his boxing career (32 wins, 4 losses and 1 draw) were only to these two. Ali could boast of beating opponents who were Heavyweight champions (Sonny Liston and Floyd Patterson), but Frazier had none of that record.

Then, Frazier misunderstood the reasons why Ali became a global icon. In his autobiography, Frazier had noted the following about Ali’s confrontation with Uncle Sam.

“For his refusal to be inducted, he was convicted of draft evasion, fined ten thousand dollars, and sentenced to five years in prison, pending appeal.

‘What can you give me, America?’ he said, after the WBA stripped him of his title. ‘You want me to fight a war against people I don’t know nothing about. You want me to go get some freedom for other people when my own people don’t have freedom at home?’

It sounded like a bunch of bullshit to me – words to justify his actions. Me, I was married with children, which made me ineligible for the draft. But if I’d been single, like Ali, I’d have had no problem serving this country if that draft board had called me. In fact, I tried to join the military when I was fourteen, but wasn’t accepted. Ours is a great country, and worth defending. What Clay did was to make himself out as a man of conscience instead of the draft dodger he was.”

Here, Frazier in fact exhibits his political ignorance. In 1960s, America was not under any threat from Vietnamese. Thus, Frazier’s reasoning that “Ours is a great country, and worth defending.” is nothing but baloney. Ali’s was one of the powerful voices among sportsmen that protested the power display of American politicians in Washington. There were other powerful American voices too (among scientists, musicians, artists, writers) who protested the Vietnam War.

I conclude that though Ali had his human faults, NOT exhibiting ‘greatness’ among his contemporaries, was not one of these.