by Sachi Sri Kantha, February 9, 2014

Tambiah SJ (1997) a rejoinder to ‘Buddhism Betrayed’ book review by Sasanka Perera

Tambiah SJ (1997) on 1983 ethnic riots in Sri Lanka

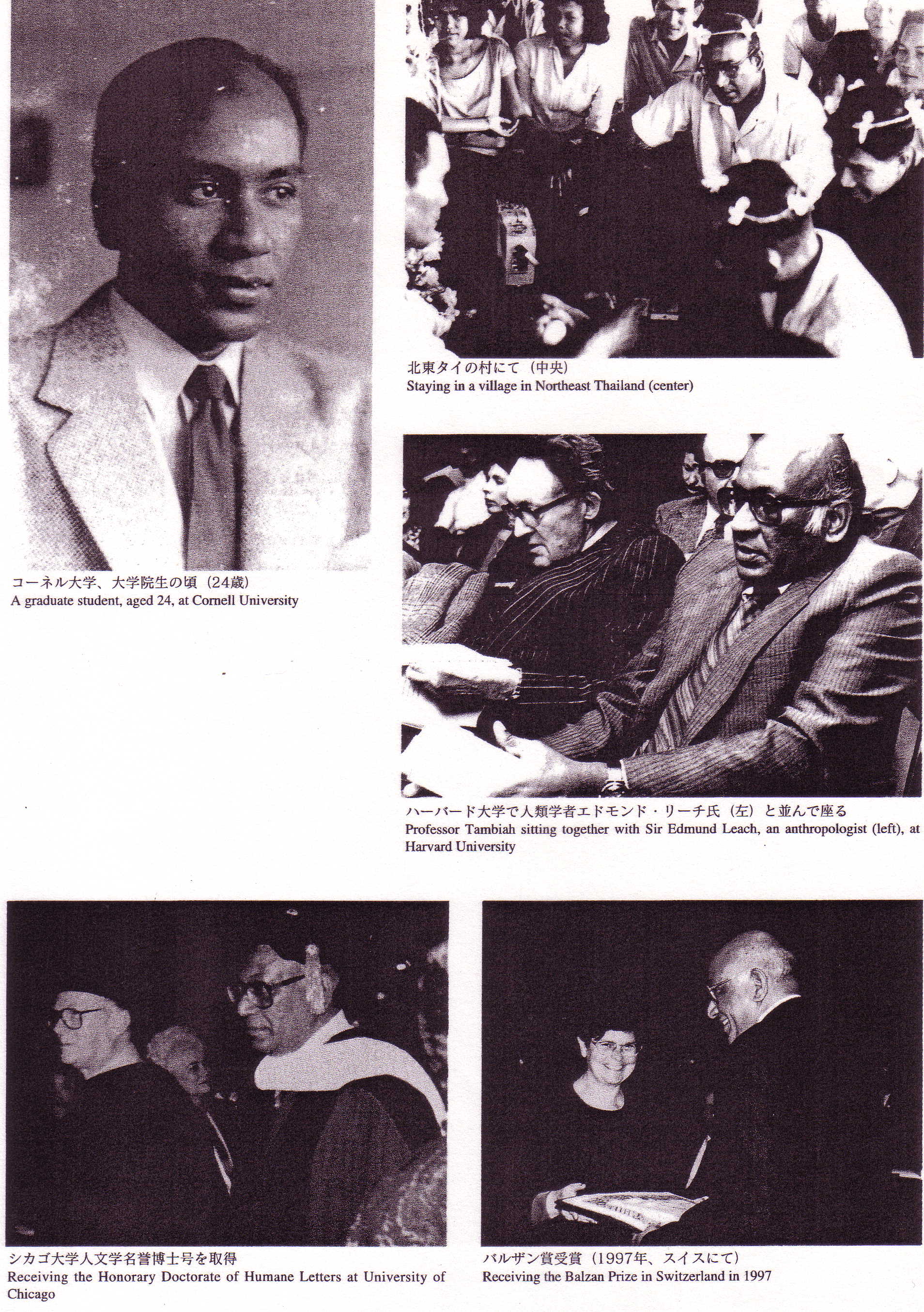

Today the phrase ‘superstar’ had lost its glamor due to excessive overuse on entertainers and sports personalities. But, in the academic arena, the usage of the ‘superstar’ accolade is offered only to deserving individuals. There is hardly any doubt that among the 20th century anthropologists, Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah (1929-2014) was a superstar. Some chauvinist Sinhalese loudmouths will not agree, but, the eulogies presented by Tambiah’s colleagues, including a few Sinhalese academics like H.L. Seneviratne (Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah: anthropologist and patriot, in Colombo Telegraph, Jan. 25, 2014) and G. Usvatte-aratchi (Professor S.J. Tambiah, a scholar of great distinction and a man of endearing charm, in The Island, Feb.2, 2014) do justice to Tambiah’s academic brilliance and personal charm.

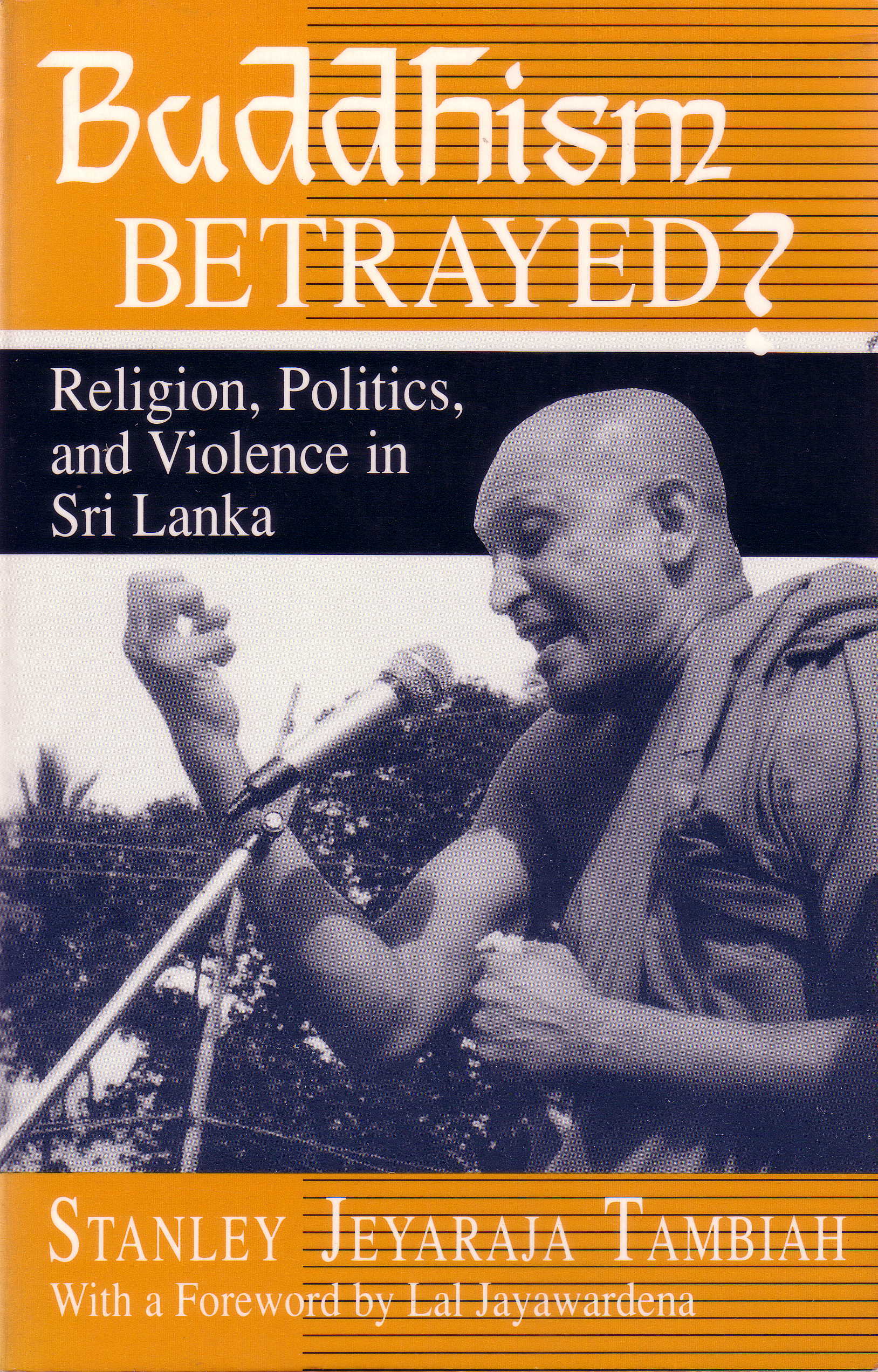

I never had an opportunity or luck to meet Professor Tambiah in person or communicate with him. Two decades ago, when I was contemplating a career move to USA for a postdoctoral stint, one of his kinsman and another Tamil academic, Prof. Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson (with whom I corresponded occasionally) did advise me to contact him. Since my degrees were in natural sciences, I couldn’t make up my mind to switch to anthropology as a career alternative, though I had an avid interest in medical anthropology and published a book on prostitutes as well as couple of sociological research studies during my Sri Lankan phase. Considering the perennial funding problem that I have to arrange for my prospective field work, I gave up on following the anthropology road. It was during that time, that Tambiah’s ‘Buddhism Betrayed? Religion, Politics and Violence in Sri Lanka’ book made waves. I published my review of that book, in the print edition of Tamil Nation (London). For record, I provide it below in entirety.

My Original Book Review [courtesy: Tamil Nation, November 15, 1992]

My Original Book Review [courtesy: Tamil Nation, November 15, 1992]

Can anyone guess the number of Buddhist monks (bhikkus) currently living in Sri Lanka? According to a statistic provided by Rene Gothoni, in the research article ‘Caste and kinship within Sinhalese Buddhist monasticism’ (which appeared in the book, South Asian Religion and Society, 1986), there were about 17,000 Buddhist monks in 1973.

Given that the bhikkus are not allowed to marry and raise families, the number of monks is solely dependent on the new recruits to the Order. Assuming that the number of new recruits to the Order remains almost equal to the number who leave the Order and those who die annually, one can infer that the number of bhikkus should remain static. So the current population of bhikkus in Sri Lanka should fall between 17,000 and 20,000. This number is predominantly distributed among the 5,000 – odd monasteries in the island. These monasteries are divided into three main sects, known in Sinhalese as nikayas. They are, according to Gothoni,

(1) Siyam Nikaya (founded in 1753) – about 2,500.

(2) Amarapura Nikaya (founded in 1802) – about 1,500.

(3) Ramanna Nikaya (founded in 1864) – about 1,000.

Gothoni also informed that the main difference between these three Nikayas is in the practical principles involved in recruiting the novices. Amarapura Nikaya and Ramanna Nikaya originated as a protest against the Siyam Nikaya’s established tradition of recruiting novices only from the Goyigama (cultivators) caste of Sinhalese.

The book in review tells the story of how bhikkus belonging to these three Nikayas have influenced the Sinhalese politics in Sri Lanka during the past century. The author of this book, S.J. Tambiah, is a professor of anthropology at Harvard University and curator of South Asian Ethnology at the Peabody Museum.

In the introduction, Tambiah writes, “What I propose to do is cover a whole century, say from the 1880s to the 1980s, focusing on the main landmarks and watersheds that figure in the story of how Buddhism as a collective and public religion was interwoven with the changing politics of the island and how that meshing contributed to ethnic conflicts, especially to various violent episodes such as civilian riots and insurrections.”

It was also written not for Sri Lankan specialists, but for “general readers, both inside and outside of academia.” The book begins with a brief chapter on the anti-Christian movement initiated by bhikkus such as Migettuwatte Gunananda and Hikkaduwe Sumangala in the mid-19th century and spearheaded by the Sinhala Buddhist lay activists like Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933) and Piyadasa Sirisena, in the first two decades of this century.

1920s saw the emergence of the symbiotic relationship between the Sinhalese politician and the bhikku. In the 1920s, the trade union leader and politician A.E. Goonesinha had the support of radical monks Boose Dhammarakhita and Udakandawela Siri Saranankara, who contributed to Goonesinha’s political journal and addressed his various ‘strike meetings’. The pioneer labour leader gradually turned into a communal politician (to protect his political turf) by espousing hatred against the Indian labourers working in the Colombo municipality.

Old timers will remember that President Premadasa originally cut his political teeth under A.E. Goonesinha, before becoming an active UNP member. When the 1930s rolled in, the LSSP politicians blazed the Sri Lankan politics as ‘radical chics’ campaigning against the British imperialism by espousing Marxist-Trotskyist socialism.

They found support from bhikkus Udakandawela Siri Saranankara, Balangoda Ananda Maitreya and Naravila Dhamaratna. In the 1947 general election also, many of the radical monks supported the Leftist parties (LSSP and Communist Party). Walpola Rahula and Kallalelle Anandasagara explicitly campaigned for the LSSP candidate Edmund Samarakkody against the prospective prime minister D.S. Senanayake in his Mirigama constituency. This set the precedence for active courting of bhikkus by the newly formed SLFP.

The leader of SLFP, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, a born Catholic Christian, tried to outsmart his political opponents by pampering the egos of bhikkus such as Henpitagedera Gnanasiha and Buddharakkitha. He reached the pinnacle of power in 1956. But he met his tragic death in 1959, falling a victim at the hands of a bhikku Talduwe Somarama, who was set up by none other than the high priest of Kelaniya temple, Buddharakkitha (himself, a founder member of the SLFP).

How much money Buddharakkitha spent on the SLFP election campaigns to gain patronage came to limelight during the Bandaranaike murder trial. In the 1952 election, Buddharakkitha had spent, “50,000 to 60,000 rupees” supporting Wimala Wijewardene (the SLFP candidate) against J.R. Jayewardene for the Kelaniya constituency. Wijewardene lost that election. In the 1956 election, which propelled S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike to power, Buddharakkitha had spent “over 100,000 rupees on the SLFP election campaign” without deriving any material benefit from the elected politicians, which led to the murder of his patron. Due to the public revulsion of the involvement of monks in the murder of the prime minister, Tambiah observes that in the twin elections of 1960, “the monks were not by and large visible and active.”

How much money Buddharakkitha spent on the SLFP election campaigns to gain patronage came to limelight during the Bandaranaike murder trial. In the 1952 election, Buddharakkitha had spent, “50,000 to 60,000 rupees” supporting Wimala Wijewardene (the SLFP candidate) against J.R. Jayewardene for the Kelaniya constituency. Wijewardene lost that election. In the 1956 election, which propelled S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike to power, Buddharakkitha had spent “over 100,000 rupees on the SLFP election campaign” without deriving any material benefit from the elected politicians, which led to the murder of his patron. Due to the public revulsion of the involvement of monks in the murder of the prime minister, Tambiah observes that in the twin elections of 1960, “the monks were not by and large visible and active.”

The volatile and “political” monk of the 1960s was Henpitagedera Gnanasiha (belonging to the Ramanna Nikaya) who was purported to be involved in the unsuccessful 1966 coup against the UNP government. Tambiah informs us that, Gnanasiha began his career as a supporter of D.S. Senanayake, the first Ceylonese prime minister, and then switched his allegiance to S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. Following the death of the founder of the SLFP, though Gnanasiha “supported Mrs Bandaranaike, he fell out with her and was kept at a distance by the SLFP”.

Tambiah also describes the activities of four bhikkus who became popular and prominent in the 1970s and 1980s. These were,

Madihe Pannasiha Thero (head monk of Vajiraramaya, Bambalapitiya; Amarapura Nikaya)

Maduluwave Sobhita Thero (head monk of Naga Viharaya, Kotte)

Palipane Chandananda Thero (head monk of Asgiriya chapter of Siyam Nikaya)

Muruttetuve Ananda Thero (incumbent of Abhayaramaya, Narahenpita)

Madihe Pannasiha Thero first came to prominence as a member of the Betrayal of Buddhism (1956) report in which he identified himself as a ‘strong nationalist and a critic of the Roman Catholic Church and its activities.’ Since 1977, he had turned his guns against the Eelam liberation movement. The political patrons of other three bhikkus have been identified in the book. Sobhita Thero was initially sponsored by the UNP minister Ananda Tissa de Alwis, though he later switched his sympathies to the SLFP. He was the founder of the Sinhala Bala Mandalaya in 1982. The front cover of the book features an arresting oratorical posture of this monk.

Chandananda Thero of Kandy was also initially a supporter of the UNP minister E.L. Senanayake, and later he drifted towards Mrs. Bandaranaike. He was the founder of the Jatika Peramuna in 1985. Ananda Thero’s patron was again the UNP politician M.D.H. Jayewardene, who as minister of health, appointed the monk as chaplain to the Nurses Union. Tambiah observes that ultimately Ananda Thero’s sympathies ‘gravitated toward the radical but chauvinist rhetoric of the JVP’.

The author also has summarized the ethnic riots of 1915 (pp.7-8), 1958 (pp.51-57) and 1983 (pp.71-75). However the details of the 1977 ethnic riots, which followed the general election victory of the UNP, has been left out. Tambiah, while noting that, “for some 16 or 17 years, from 1960 to 1977, there were no anti-Tamil riots or any form of collective violence against ethnic minorities” suggests that this was due to the fact that “between 1960 and the early 1970s the aspirations and objectives of militant lay Buddhists and politically ardent Buddhist monks with regard to the restoration of Buddhism to a pre-eminent place had been largely addressed and fulfilled.”

One aspect which has not been covered in the book which I felt deserved inclusion was the positive contributions of some bhikkus to the Tamil culture. For instance, Hisselle Dhammaratna Thero was recognized Tamil scholar who contributed research papers at the International Tamil Research Conferences held in the 1960s and 1970s. Before being awarded a B.A. (Ceylon) degree in 1953, he passed the Tamil Pundit exam in 1946 and translated Tamil epics Silappadikaram andManimekalai to the Sinhala language. In 1964, he also wrote a paper on the ‘Tamil influence on Sinhala’. A few other monks such as Hevanpola Ratnasara Thero have contributed their wisdom for communal harmony. These contributions in the non-political arena deserve equal recognition as well.

I also spotted a few factual errors in dates and names. These include the following: (1) In 1958 the proscribed extremist Sinhalese party is identified as ‘Janatha Vimukti Peramuna’ (p.55). Actually, its name was Jatika Vimukti Peramuna, led by K.M.P. Rajaratne. Janatha Vimukti Peramuna made its entry into the Sri Lankan political lexicon only in 1971. (2) J.R. Jayewardene was in power until 1988, not ‘until 1987’ as noted in p.63. (3) The unsuccessful coup in which Gnanasiha Thero participated took place in 1966, and not in ‘1964’ (p. 104).

In sum, Prof. Tambiah’s book is an important contribution to the Eelam and Sri Lankan political literature. Like a honey bee which gathers the honey from a multitude of flowers and produces a nourishing nutrient, Prof. Tambiah also has produced this work, based on the material previously presented by Urmila Phadnis, James Manor, Bruce Kapferer, Stephen Kemper, K.N.O. Dharmadasa, K.M. de Silva, Gananath Obeyesekere and Kumari Jayewardena.

Synopsis of Tambiah’s Career

Apart from this controversial book, I also enjoyed reading Tambiah’s earlier book on Sri Lanka; namely, ‘Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy’ (1986). In this book, Tambiah expressed his views on the 1983 anti-Tamil riots. Tambiah also published a subsequent book covering the Sinhala-Tamil ethnic conflict, ‘Leveling Crowds: Ethnonationalist Conflicts and Collective Violence in South Asia’ (1996). To sum up the career ladder of Tambiah, he received his B.A. from the then University of Ceylon with First Class honours in 1951. Then, he proceeded to Cornell University for a Ph.D. (Sociology, Social Anthropology and Social Psychology), which was granted in 1954. His Ph.D. thesis was entitled, ‘The process of secularization in three Ceylonese peasant communities’ (391 pages plus 39 tables). For this thesis, he studied the impact of modernization process on three Sinhalese villages – one in Dry Zone, one in Kandyan region, and the third a newly settled ‘pioneer colony’. Tambiah was a lecturer at the University of Ceylon from 1951 to 1960. Then, he served as a UNESCO Technical Assistance Expert in Thailand from 1960 to 1963. From Thailand, he moved to the University of Cambridge as lecturer from 1964 to 1972. Then, his next move was to USA, as a professor in anthropology at the University of Chicago. From Chicago, Tambiah finally settled as a professor in anthropology and Curator of South Asian Ethnology, Peabody Museum, at Harvard University.

Apart from the Balzan Price (from Fondation Internationale Prix E. Balzan – Fonds) awarded to Tambiah in 1997, he was also awarded one of the four 9th Fukuoka Asian Cultural Prizes (Japan) in 1998, under the International Category of Academic Prize. The award citation for this prize partly reads as follows:

“His trilogy of Thai studies, consisting of Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in Northeast Thailand and two other monographs, is a work of detailed ethnography and historical anthropology. Its discussion of rituals, state and charisma has earned it the status of a classic. In addition, the theoretical thoughts reflected in his ‘Culture, Thought and Social Action’ and ‘Magic, Science, Religion and the Scope of Rationality, continue to influence theories of symbol and ritual.

In 1983, the intensified ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka marked a turning point for Professor Tambiah and led to a renewal of his Sri Lankan research, which had been interrupted by Thai studies and various professional commitments. Since then, he has actively voiced his opinions on the interplay between religion, politics and society in Sri Lanka, focusing on such factors as conflict, violence and Buddhism….”

Autobiographical Snippets

In the Epilogue (chapter 9) of his ‘Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the dismantling of Democracy’ (1986) book, Tambiah provided some details about his family and father’s career. Excerpts:

“…My parents’ forbears had become Anglican Christians, while large numbers of their kin remained Hindu. My father was for the most part educated in Colombo’s public schools (St. Thomas and Wesley), became a lawyer, and returned to Jaffna to practice his profession and indulge his hobby as a ‘Planter’. He was a close friend of Arunachalam Mahadeva, the son and nephew respectively of two famous Tamil politicians, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam and Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, who together with Sinhalese politicians led the Ceylon National Congress in the early decades of the twentieth century. Mahadeva was the only Tamil minister in the Donoughmore era, and was in turn a close friend of Senanayake and a founding member of the UNP. My father, though not politically inclined, consented, as an ally of Mahadeva, to contest the first parliamentary elections in 1947 under the UNP ticket, at a time when the Tamils of Jaffna were closing ranks behind a purely Tamil party, the Tamil Congress, led by a fiery orator, G.G. Ponnambalam, who had vainly argued before the Soulbury Commission for more minority safeguards in the proposed constitution. As expected, my father and Mahadeva were heavily defeated. Subsequently Mahadeva was honored with a knighthood and my father was awarded the Order of the British Empire. My family (together with a few others in Jaffna) have remained for a long time loosely and sentimentally attached to the secularist, noncommunalist, nationalist postures and goals of the Senanayakes, though none of them has actively engaged in politics again.”

Tambiah’s father C.R. Thambiah (this is how the name was spelt in the Parliamentary Elections of 1947 book, published by Lake House, Colombo) contested the Chavakachcheri constituency as a UNP candidate and polled only 2,002 votes and lost badly to Tamil Congress candidate V. Kumaraswamy who polled 11,813 votes, among the 14,001 votes cast.

In the same chapter, Tambiah had touched a little on his budding academic career in Ceylon during 1950s, and how he experienced the 1958 anti-Tamil riots in a paragraph. I reproduce this paragraph below.

“In 1958, while I was leading a research team composed of university undergraduates, all of whom were Sinhalese, that were engaged in a sociological study of peasant colonization in Gal Oya, ethnic riots unexpectedly broke out in our midst, and at Amparai, Sinhalese public workers went on the rampage in hijacked trucks, attacking Tamil shopkeepers and Tamil peasant colonists. My students, very solicitous for my safety, insisted that I stay behind closed doors while they stood guard. And I was later hidden in a truck, and spirited out of the valley to Batticaloa, a safe Tamil area. That experience was traumatic: it was the first time the ethnic divide was so forcibly thrust into my existence. And intuitively reading the signs, I wished to get away from the island, for I experienced a mounting alienation and a sense of being homeless in one’s own home.”

Even Harvard University professors are not immune to bias! If Tambiah’s allegiance to truth has to be questioned, I’d comment that he was partial to the political record of Don Stephen Senanayake, Ceylon’s first prime minister from 1948 to 1952. Despite the fact that the Gal Oya anti-Tamil riots from which he suffered in 1958, Tambiah conveniently ignored the reality of vital contribution of D.S. Senanayake in creating such an explosive situation in late 1940s. Majority of Tamils will never agree with Tambiah’s endorsement of Senanayake’s politics as “non-communalist attitude toward the island’s minority groups – Tamils, Muslims and Eurasians – was partly influenced by the pragmatic realization that the British would not countenance progress toward independence unless he and other Sinhalese leaders came to a reasonable understanding with the minorities. But his noncommunalist, nonreligionist, and pro-constitutionalist attitude was also fostered by the kind of education he received and the kind of elite members of all ethnic groups he consorted with at the St. Thoms’ College.” Majority of Tamils do consider that Don Stephen Senanayake was a wily ‘closet’ Sinhalese racist who duped the Colombo Tamils like Tambiah’s father with his noncommunalist prattle.

Tambiah’s Research Papers

For record, I provide below a listing of Tambiah’s 28 research papers in chronological order. I assembled this from authentic data bases. As of now this list, spanning half a century (1955-2005), has not appeared in eulogies to Professor Tambiah which I have checked. I provide this list for one reason. There exists a pack of anthropologists cum journalists and opinion peddlers among Sinhalese who had criticized Tambiah’s studies, because they found it uncomfortable to digest the truths revealed. But, they have hardly published in peer-reviewed international journals to confront Tambiah’s data. I also provide PDF files of two his publications that appeared in 1997; one was his observations about the 1983 anti-Tamil riots (published in Social Science and Medicine journal), other was his rebuttal to a review of his Buddhism Betrayed? book (published in American Ethnologist journal).

Tambiah, S.J.: Ethnic representation in Ceylon’s higher administrative services, 1870-1946. University of Ceylon Review (Peradeniya), 1955 April-July; 13(2 & 3): 113-134.

Tambiah, S.J.: Ritual and drama in a devil dancing ceremony. Thunapaha (University of Ceylon, Peradeniya), 1956 January; 1(2): 28-31.

Tambiah, S.J. and Ryan, B.: Secularisation of family values in Ceylon. American Sociological Review, 1957 June; 22(3): 292-299.

Tambiah, S.J.: A sociological approach to the problem of crime: a study of criminal behavior resulting from social disruptions and deviational pressure under ‘slum’ conditions. Probation and Child Care Journal (Colombo), 1957 June; 1(2): 20-37.

Tambiah, S.J.: The structure of kinship and its relationship to land possession and residence in Pata Dumbara, Central Province. Journal of Royal Anthropological Institute (London), 1958 Jan-June; 88(1): 21-44.

Tambiah, S.J.: Some sociological problems of colonization on a peasant framework. Ceylon Economist (Colombo), 1958 December; 4(3): 238-248.

Tambiah, S.J.: Ceylon. In: The role of savings and wealth in Southern Asia and in the West, Richard D.Lambert and Bert F.Hoselitz (eds.), UNESCO, Paris, 1963, pp. 44-125.

Tambiah, S.J.: Kinship fact and fiction in relation to the Kandyan Sinhalese. Journal of Royal Anthropological Institute (London), 1965; 95(2): 131-173.

Tambiah, S.J.: Polyandry in Ceylon, with special reference to the Laggala region. In: Caste and kin in Nepal, India and Ceylon: Anthropological Studies in Hindu-Buddhist contact zones, Christoph von Furer-Haimendorf (ed), Asia Publishing House, Bombay, 1966, pp. 264-358.

Tambiah, S.J.: The politics of language in India and Ceylon. Modern Asian Studies, 1967 July; 1(3): 215-240.

Tambiah, S.J.: The caste system in Ceylon. In: Caste and Race: Comparative Approaches, A Ciba Foundation volume.. Anthony de Reuck and Julie Knight (eds.), J & A. Churchill, London, 1967, pp. 88-90.

Tambiah, S.J.: The magical power of words. Man, 1968 June; 3(2): 175-208.

Tambiah, S.J.: Buddhism and this worldly activity. Modern Asian Studies, 1973 January; 7(1): 1-20.

Tambiah, S.J.: Dowry and bridewealth, and property rights of women in South Asia. In: Bridewealth and Dowry, Jack Goody and S.J.Tambiah (eds.), Cambridge Papers in Social Anthropology, no.7, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1973, pp. 59-169.

Tambiah, S.J.: Form and meaning of magical acts: a point of view. In: Modes of Thought – Essays on Thinking in Western and non-Western Societies, Robin Horton and Ruth Finnegan (eds.), Faber, London, 1973, pp. 199-229.

Tambiah, S.J.: The persistence and transformation of tradition in Southeast Asia, with special reference to Thailand. Daedalus, 1973 Winter; 55-84.

Tambiah, S.J.: The cosmological and performative significance of a Thai cult of healing through meditation. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry, 1977 April; 1(1): 97-132.

Tambiah, S.J.: At the confluence of anthropology, history and Indology. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 1987 January-June; 21(1): 187-216.

Tambiah, S.J.: The Buddhist conception of kingship and its historical manifestations : a reply to Spiro. Journal of Asiatic Society, 1978 August; 37(4): 801-809.

Tambiah, S.J.: Ethnic-conflict in the world today. American Ethnologist, 1989 May; 16(2): 335-349.

Tambiah, S.J.: Bridewealth and dowry revisited – the position of women in sub-Saharan Africa and north India. Current Anthropology, 1989 August-October; 30(4): 413-435.

Tambiah, S.J.: Sri Lanka – Introduction. Journal of Asian Studies, 1990 February; 49(1): 26-29.

Tambiah, S.J.: Reflections on communal violence in South Asia – Presidential address. Journal of Asian Studies, 1990 November; 49(4): 741-760.

Tambiah, S.J.: On the subject of Buddhism Betrayed? A rejoinder. American Ethnologist, 1997 May; 24(2): 457-459.

Tambiah, S.J.: Friends, neighbors, enemies, strangers: Aggressor and victim in civilian ethnic riots. Social Science & Medicine, 1997 October; 45(8): 1177-1188.

Tambiah, S.J.: What did Bernier actually say? Profiling the Mughal empire. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 1998 July-December; 32(2): 361-386.

Tambiah, S.J.: Transnational movements, diaspora and multiple modernities. Daedalus, 2000 Winter; 129(1): 163-194.

Tambiah, S.J.: Urban riots and cricket in South Asia: a postscript to ‘Leveling Crowds’. Modern Asian Studies, 2005 October; 39: 897-927.

A paper evincing erudition in that it concisely captures Thambiah’s life, the work and his intellectual attainment and contribution in a nutshell making it easy to read in a manner that SJ himself would have perhaps liked. Thanks to Satchi. Subra

[…] Number Rises to 61 USTPAC – International Probe a Must in Sri Lanka Briefing by UNSG Spokesman Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah (1929 – 2014) Break in Siege Is Little Relief to Syrian City March Madness: Is it USA Vs India? Making Provincial […]