By T. Sabaratnam, 2003

Volume 1, Introduction, Part 2

Original Chapter 1

Why didn’t he hit back?

“Why didn’t he hit back,” was Pirapaharan’s reaction when he heard from his father, Thiruvenkadam Velupillai, about the burning of the Panadura Pillayar Kovil priest.

His father, an admirer of the Federal Party Leader Samuel James Velupillai Chelvanayakam, had no answer. Tamils like him then believed in Gandhian non-violent protest to win their rights. They believed that sitting cross-legged on the dusty Galle Face Green, singing hymns and praying for divine intervention and a change of heart among the Sinhala leadership would earn them their lost rights.

Panadura Pillayar Kovil

For the three and a half year old ‘thurai’ hitting back sounded more natural and practical. His parents, especially his mother, Parvathipillai, Parvathi in brief, called him ‘thurai’, meaning master, which he really was at his home, his wish granted by the parents and obeyed by his sisters and brother. Pirapakaran, the youngest of the four, was his father’s darling and during childhood slept with him. He was born in the Jaffna Hospital on 26 November 1954.

Pirapaharan routinely sat with his father and his friends during their regular evening chat sessions. He was with them when they discussed the events of June 1956, the passage of the Sinhala Only Law, the Galle Face satyagraha, the Sinhala attack on the peaceful protesters, the spread of attacks in Colombo and the chasing of Tamils from Gal Oya, the signing of the historic Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact, its abandonment and the consequent riots of May 1958 and the cruel burning of the Panadura priest.

Pirapaharan as a child

By then the Sinhala-Tamil discord had grown and was threatening the foundation of the unitary character of the Sri Lankan state. The state-aided Sinhala colonization of the Tamil majority east and southern borders of the north had grown into an emotional clash. The deprival of the citizenship rights of nearly a million Indian Tamils had burrowed into the Tamil mind enduring distrust about Sinhala intentions. The denial of official status to the Tamil language had inflamed Tamil feeling. These three discriminatory factors had strengthened Chelvanayakam’s demand for an autonomous unit for the Tamil majority north-east under a federal, united Sri Lanka, first proposed in 1948 and adopted by the Tamil people in the parliamentary election of 1956.

Since then, in June 1956 and May 1958, another serious factor, the safety and security of the Tamils was added as the fourth to the three already injuring Sinhala-Tamil concord. On 5 June 1956 an organized band of Sinhala hooligans, led by two government parliamentarians, attacked and humiliated about 250 Tamils who chose to stage a non-violent sit-down protest called satyagraha on the Galle Face Green near the then Parliament building. The crowd, thrilled with their success in quelling the Tamil protest, trailed the satyagrahis, who came from the eastern province, hooting and pelting stones, as they marched to the Fort railway station to board a Batticoloa-bound train. The crowd, that had swelled into a mob by then, attacked the Tamils in Colombo and on the following day another mob attacked the Tamils in Gal Oya, at a formerly Tamil village called Paddipalai, and chased all of them out of the area. The cleansing the Tamils from their traditional villages had begun.

In May 1958 the attack was widespread and premeditated. It was aimed at weakening the hold the Jaffna Tamil trading community had on the Sri Lankan economy. The entire Tamil trading network in Southern Sri Lanka was attacked. Shops in the provincial towns were looted and burnt. Hindu temples were also not spared. Tamil border villages were uproote

d and their occupants chased away making room for Sinhala encroachers.

A large number of Tamil families was rendered refugees and the Bandaranaike government transported them under armed escort to the north and east where, they were told, they really belonged. The riots that injured Tamil pride had thus laid the foundation in the Tamil mind for the concept of a homeland where they could live in safety and with dignity.

Velupillai, a district land officer, foresaw the impact of Sinhala colonization and the riots on the future of the Tamil race and discussed those matters at his evening chats. He kept repeating Chelvanayakam’s slogan: “the wall must stand to do the painting,” meaning that land must be protected if Tamil people are to survive as a distinct race.

Pirapaharan’s initiation to politics is through these discussions. He listened intensely to what the elders discussed. He did not participate in them. That trained him to be a patient listener, a valuable asset and a trait of his character.

Pirapaharan’s anger was natural when he listened to the story of the burning of the priest. “Why didn’t he hit back?” he asked. The priest and the Tamils should have fought back, he argued.

The priest could not hit back. He had heard that morning that Sinhala mobs were gathering on the streets of Colombo and by noon they were looting and burning Tamil shops, Tamil-owned establishments and Tamil houses. He had also heard that hooligans had entered government offices, dragged out hiding Tamil officers and thrashed them.

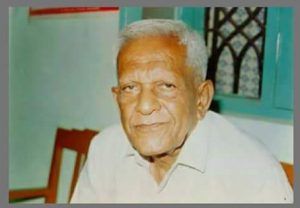

Thiruvenkadam Velupillai

The priest was frightened when a crowd gathered at Panadura junction and marched threateningly towards the temple. He ran to his room and hid under his wooden bed. The shrieking crowd found the shivering priest, caught him by his hands and hair and dragged him outside the temple. It dowsed him with petrol brought from the nearby pumping station and set him alight. The priest writhed and the crowd yelled, chanting the slogan that that would teach the ‘parai themala’ (Tamil paraiahs) who demanded equal status for their language, Tamil, a proper lesson.

The burning of the priest hurt Tamil Hindus greatly. It pained little Pirapaharan more, for he was brought up in a highly religious environment. His parents were descendants of families that built temples. His father Velupillai was the trustee of the Valvettithurai Vaitheeswaran Kovil, known as Valvai Sivan Kovil, the biggest of the three Hindu Temples in the harbour town of Valvettithurai. It was built by Pirapaharan’s ancestor, Thrumeniyar Venkatachalam. Pirapaharan’s ancestors had also assisted in the construction of the other two temples: Nediyakadu Pillayar Kovil and Vallai Muthumari Amman Kovil.

Pirapaharan’s mother, Vallipuram Parvathypillai, was also from a temple building family, ‘methai veeddu’ Nagalingam family, of Point Pedro, another northern port. She was deeply religious, fasting and observing the numerous festivals. As trustee the father and as devotee the mother spent most of their time in temple work and Pirapaharan was constantly with them.

The shrine room in their home had a large statue of Shiva and smaller ones of Vinayagar and Murugan. The children were required to pray every morning and to take turns in reciting Hindu hymns, thevarams. Pirapaharan was the devotee of Murugan, the God of action and destroyer of evil.

On the wall were hung the pictures of other gods and Indian leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Velupillai, an admirer of Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu revivalist, added his picture also. Pirapaharan added two more: Subash Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh, the Indian freedom fighters who preferred the path of armed struggle.

Valvettithurai, a prosperous trading port and boat building yard during the days of the Jaffna Kingdom and later during the Dutch and Portuguese rule (for over 1000 years ending early 19th century) declined in importance in early in the nineteenth century after the British brought the country’s trade under its control. The daring trading and seafaring men of Valvettithurai continued their sea trading, defying the British rulers who called them smugglers. They often clashed with the police deployed by the British masters and later with the army posted in the late fifties along the winding northern coast to curb smuggling. Valvettithurai residents, a tightly knit 10,000 strong community, detested the army for its brutality during their searches.

Valvettithurai, VVT in brief, served as a “smuggler’s paradise” where all goods forbidden by the “socialist” state of Sri Lanka were available in plenty. The brave sailors of VVT traveled the choppy seas to the Tamil Nadu and Myanmar (formerly Burma) coasts to bring in the contraband and amass great wealth. They fought daring battles with the army’s coast guard and the fledgling navy that patrolled the coastal waters.

The annual festival of Valvai Sivan Kovil was celebrated with grandeur. Top nathaswaram and bharatha natyam artistes were brought from Tamil Nadu to perform during the festival. In late fifties and sixties Swami Kirupanantha Variyar was brought to give musical discourses. Velupillai was Variyar’s admirer and he kept his pet son, Pirapaharan, to be in attendance. He also took his family to listen to Variyar’s discourses whenever he visited the Jaffna peninsula. Pirapaharan, pious like his mother, respected the sagacious holy man and sought his blessing during every visit. The preacher enjoyed answering the searching questions of the wide-eyed youngster. Variyar once told Pirapaharan’s mother that her stocky son would one day emerge a Hindu revolutionary. His penetrating questions made Variyar to see in him a revolutionary.

Pirapaharan was naturally upset when he learnt about the burning of the priest. He has disclosed that to most of his interviewers. He told N. Ram, then of The Hindu, in mid 1986:

Ours is a god-fearing society and people are religious-minded. The widespread feeling was: when a priest like him was burnt alive, why did we not have the capability to hit back. That was one atrocity that made people think deeply.”

Earlier in 1984 he told Anita Prathap in Chennai that the burning of the priest had made him very angry and he repeated this sentiment in 1994 in his interview to Velicham, a Tamil magazine. Priests of any religion are venerable to the followers of that religion, he maintained and added that Sinhala Buddhists who burnt a Hindu priest alive should be made to repent.

Aunt’s Burnt Face

Pirapakaran’s reaction when he saw his aunt’s burnt face was more violent. The aunt visited them at their home in Alady Lane at Valvettithurai, nearly a year after the riots of May 1958. Her face and hands bore the scars of burning.

“How did Aunty got burnt?” Pirapakaran asked his mother.

She was burnt during the riots, his mother disclosed.

Pirapakaran and his sisters, Jagatheeswari, the elder, and Vinothini, pleaded with the Aunty to relate the incident to them.

“I was living with my husband and children in Colombo,” the aunt told the children and described the mob attack on her house. “We hid ourselves in the toilet. They set fire to it, too. Then we tried to escape and they caught my husband and clubbed him to death. I jumped over the rear wall, a fire ball. The children followed me. Neighbours, good Sinhala people, took me to the hospital. I am living like this, a memento of Sinhala brutality and kindness,” she said.

The details the aunt gave about the cruel acts of the crowd made the two girls sullen and Pirapakaran boil. The girls shrieked when aunty told them how a gang tore an infant from a mother and flung it into melting tar. Pirapakaran fell silent. He was angry.

Twenty- five years later, in 1984, Pirapaharan recalled to Anita Pratap, his feelings, thus:

During the riots a Sinhala mob attacked her house in Colombo. The rioters set fire to the house and murdered her husband. She and her children escaped with severe burn injuries. I was deeply shocked when I saw the scars on her body. I also heard stories of how young babies were roasted alive in boiling tar. When I heard such stories of cruelty I felt a deep sense of sympathy and love for my people. A great passion overwhelmed me to redeem my people from this racist system. I strongly felt that armed struggle was the only way to confront a system which employs armed might against unarmed, innocent people.

Pirapaharan told his aunt that Tamils should hit back and he reasoned: “If they know that we would hit back, they will not do such things.”

Prabakaran as a teen

Pirapaharan was angry that the Sinhala leadership had allowed hooligans to attack and humiliate the Tamil people. He was also annoyed and angry with the Tamil leadership for not responding in the appropriate manner and for continuing to preach non-violence. He had no way to pour out his feelings. He was young and his father, Velupillai ,was a strict disciplinarian.

Pirapaharan recalled to Ram the environment in which he grew up:

I was brought up in an environment of strict discipline from childhood. I was not allowed to mingle freely with outsiders. I used to feel shy of girls. Great store was laid on personal rectitude and discipline. My father set an example through his personal conduct: He would not even chew betel leaves. I modeled my conduct on his: he as a government officer, a district land officer. A very straightforward man. People say in our area: When he walks, he does not even hurt the grass under his feet, but his son is so…Even while criticizing me, they marvel at the fact that such a son was born to such a father. He was strict, yes, but also soft and persuasive. In my own case, he reasoned rather than regimented and his attitude was that of a friend… he would give me certain pieces of advice and discuss things with me.

His mother and sisters also petted him and endearingly called him ‘thamby,’ meaning younger brother. He recalled in interviews the pleasant life he led at home. He told Velicham, in 1994”

As a child, I was the pet and the darling of the family. Therefore I was hedged in by a lot of restrictions at home. My play-mates were the neighbours’ children. My ‘world’ was confined to my house and the neighbours’ houses. My childhood was spent in the small circle of a lonely, quiet house.

Pirapaharan’s neighbours and relatives remember his childhood fondly. As the youngest, he ran errands to them. He played a vital role at the annual feast the family held in remembrance of his paternal grandfather. He carried lunch parcels to the relatives who failed to attend. He also distributed sweetmeats to them whenever his mother prepared anything special. He carried the temple ‘prasatham’ to his relatives after special poojas.

He continues that habit even now in his Vanni hideout. Special preparations cooked in his home, are sent to his close friends. Adele Balasingham, in her autobiography, Will to Freedom, recalls the special meals he had sent to her. She says that Pirapaharan’s special item is chicken curry. Adele, a vegetarian, says her husband, Balasingham, political advisor and negotiator of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) which Pirapaharan heads, relishs it, and adds that the considerate guerilla leader made for her special vegetarian curries, mostly innovative creations.

He continues that habit even now in his Vanni hideout. Special preparations cooked in his home, are sent to his close friends. Adele Balasingham, in her autobiography, Will to Freedom, recalls the special meals he had sent to her. She says that Pirapaharan’s special item is chicken curry. Adele, a vegetarian, says her husband, Balasingham, political advisor and negotiator of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) which Pirapaharan heads, relishs it, and adds that the considerate guerilla leader made for her special vegetarian curries, mostly innovative creations.

Neighbours and relatives say Pirapaharan’s mother was a fine cook and Pirapaharan got his culinary talents from her. Parvathy, 65 in 2003, and her husband, Velupillai, 70, returned to Jaffna on 30 May 2003 from Trichi in Tamil Nadu where they had been living since 1984. Velupillai had a stroke in early 2002. They were accompanied by their second daughter Vinothini and her husband, Rajendran, who came from their home in Canada. Vinothini was Pirapaharan’s competitor in cooking. Eldest sister Jagatheeswari Mathiyaparanam, now living in Denmark, would readily acknowledge her brother’s superiority, partly to encourage him and partly as a show of affection. His brother, Manoharan, now in Denmark, was never Pirapaharan’s competitor in anything, ‘thamby’ was so dear to him.

Pirapaharan enjoys eating. He likes non-vegetarian food, chicken is his specialty. Now his preference is Chinese food, according to Adele.

He had scrupulously inculcated in his cadres the sense of good cooking and the art of enjoying eating. An incident, related by one of the cadres to the Tamil publication Viduthalai Puligal is revealing. The Indian Peace Keeping Force had closed in on his Mullaitivu hideout. They had only cowpeas to cook. They were boiling them in the open hearth. The pot slipped while taking it off the fire. A handful of cowpeas spilled.

“I was scared. If anyone sees I would receive the normal punishment of cooking for a week. I hurriedly swept some ash and covered it. Thalaivar (leader) had seen it. “Child,” he chided me. “Why did you do it? That is sufficient for my lunch.” He collected it, washed it, and walked away munching it, asking me to temper it before giving it to others.”

She added:

“Thalaivar always insisted that the food should be clean, tasty and none should be wasted.”

Pirapaharan was playful. Teasing his sisters was his pastime during childhood. He enjoyed entertaining his mother and sisters, enacting for them the impressive and hilarious scenes in the films he saw. Once, after seeing the Tamil film ‘Parasakthi,’ released two years before his birth, he entertained his mother and sisters with Sivaji Ganeshan’s classic dialogue: kalaithan kachithan kudikkathan katpithana. After seeing the film ‘Virapandiya Kaddapomman,’ he entertained them with Kaddapomman’s reply to the British official who asked the Tamil chieftain who resisted British domination to pay up his taxes.

Prabakaran’s childhood home in VVT during the ceasefire

The series of Tamil films on the Indian independence struggle and on Tamil history instilled in him the spirit of independence and Tamil pride. ‘Kaddapomman,’ and ‘Kappal Oddiya Thamilan’ influenced him immensely. Both films kindled his spirit of resistance to foreign domination. The second, in which Chidamparanar floated a shipping company as a tool of resistance, kindled his imagination in that direction. Now the LTTE owns many ships. The films ‘,’Rajaraja Cholan which depicted the might and influence of Tamil power, and ‘Oovaya’ that portrayed the literary legacy of the Tamil people made him realize the heritage to which the present day Tamils are heir. After he entered the armed struggle his passion veered towards cowboy films and Clint Eastwood emerged his hero.

He guzzles war films, especially if they are connected to a freedom struggle. The film on the Algerian freedom fighter, Ali, in which a woman Algerian freedom fighter jumps into a French army camp with explosives tied to her waist and destroys it, excited him. He has a wide collection of videos of such films.

The sixties and seventies were also the golden years of Tamil historical novels. Tamil Nadu’s popular weeklies Anantha Vikatan, Kalki and Kumuthamvied with each other to serialize those novels. Pirapaharan, an avid reader since childhood, gulped every one of them. Kaki’s Sivagamini Sapatham and Parthipan Kanavu, Akilan’s Kadal Pura, Kausiliyan’s Pamini Pavaikal, Kaliya Perumal’s Kalukkul Eeram, and Rajaj’s Mahabaratham and Ramayanamwere his favorite novels.

Kadal Pura was the story of the Chola naval power and its conquests of Cambodia and Thailand. The Tamil naval power was at its peak under the Cholas and their command ship was named ‘Kadal Pura.’ Kallukkul Eeram was the story of India’s independence struggle and describes how a group steps out of Gandhi’s control and stages an armed attack on Madras’ Fort St. George. Pirapaharan was influenced by both.

From the historical novels, he told Velicham, he learned of the great, flourishing Tamil empires. He added:

These novels aroused in me the desire to see our nation rise again from servitude and that our people should live a life of dignity and freedom in their liberated homeland. Why shouldn’t we take up arms to fight those who have enslaved us: this was the idea that these novels implanted in my mind.

He said from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana he learnt several virtues:

‘Perform your duty without regard to the fruits of action’, says the Bhagavad Gita. I grasped this profound truth when I read the Mahabharata. When I read the great didactic works, they impressed on me the need to lead a good, disciplined life and roused in me the desire to be of service to the community.

People respond to the characters of Mahabharata in different ways and Pirapaharan responded the most to the character and role of Karuna, who readily sacrificed his life. He venerated Bhima’s obedience and selflessness He told an interviewer:

I value the character and role of Karuna the most on account of his readiness to make the ultimate sacrifice.

Discipline is the hallmark of Pirapaharan’s personal life and that of his militant group, the LTTE. He considers himself the principal of a good and disciplined school. He told Ram:

When you have a school with a good standard of discipline and a principal who believes in this, the students acquire good education and do well in life. You see this everywhere: certain schools are rated good because the teachers and, most important, the principal stand for discipline. You will find batches and batches of students who studied under such a principal do well later on. The same principle applies to our activity. That is why we lay such stress on stern discipline.

In the same interview he gave two reasons for maintaining strict discipline in the LTTE. First, a member of the LTTE, by definition, fights for the people. If he indulges in anti-social activity he becomes an enemy of the people and the LTTE would lose its clout with the people. Second,

Consider also this aspect, the status of those under arms in society. Those who bear arms acquire and wield an extreme measure of power. We believe that if this power is abused, it will, inevitably, lead to dictatorship.

His family bought Anantha Vikatan and Kalki. Neighbours bought Kalaimagal, Kumutham and Kalkandu. Pirapaharan, using his earnings, the tips he got for helping to do household chores, bought the science magazine Kalaikathir and the monthly digest Manjari. He bought them from the small bookshop in the village where he also bought his books.

Pirapaharan was a lover of books and reading was his hobby since childhood. He was especially keen on reading historical novels, works of history, and biographies of heroes. He said:

It is through books that I learnt of the heroic exploits of Alexander and Napoleon. It is through my habit of reading that I developed a deep attachment to the Indian Freedom struggle and martyrs like Subhash Chandra Bose, Bagat Singh and Balagengadhara Tilak. It was the reading of such books that laid the foundation for my life as a revolutionary. The Indian Freedom struggle stirred the depths of my being and roused in me a feeling of indignation against foreign oppression and domination.

Of all the Indian freedom fighters he was attracted to Subas Chandra Bose, who was Pirapaharan’s hero. His advocacy of armed struggle, his escape to Germany, his stealthy submarine journey to Japan, his raising of the Indian National Army and his thrust to India along with the Japanese made the charismatic Bengali nationalist Pirapaharan’s idol. Above all these, his brave words:

I shall fight for the freedom of my land until I shed the last drop of my blood

captivated and inspired Pirapaharan.

He said this to Velicham:

Above all, Subhash Chandra Bose’s life was a beacon to me, lighting up the path I should follow. His disciplined life and his total commitment and dedication to the cause of his country’s freedom deeply impressed me and served as my guiding light.

Pirapaharan is not a casual reader. He reads the book from cover to cover. He gets immersed into the book totally. After reading a book he questions ‘Why?’ ‘What for?’, ‘How did this happen this way?’

Sankar Raji, a leader of a rival militant group, the Eelam Revolutionary Organization of Students (EROS), who has known Pirapaharan since the early seventies, vouches that. He says he has seen Pirapaharan immersed in the book he was reading. He recalls some of the biographies he saw in Pirapaharan’s room: Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Ho Chi Minh and Mao Tse-tung. He said Pirapaharan was an admirer of the Vietnamese and Chinese revolutions. Shankar Raji had also seen some of the ‘Teach Yourself ‘series in Pirapaharan’s room. One of them was on Shooting.

His Education

Though mainly self taught, Pirapaharan underwent formal education. His junior school study was at Alady Sivaguru Vidyalayam, known as Alady school. His secondary education was at Valvai Chithampara College where he studied up to grade ten. He did not sit for his General Certificate of Education (Ordinary Level).

At school he was playful and classmates recall him relating the story about the burning of the Panadura priest with emotion. “Tears rolled down his plump cheeks,” recalled a classmate, now a leading trader in Colombo. He discussed with his friends most of the things he heard at his father’s chat sittings.

His hobby while returning from school was to display his skill in marksmanship with stones and the catapult. With stones he would fell mangoes and wood apples. He would also get a friend to throw up a stone and try to hit it. With a catapult he felled many squirrels.

Teachers of Chithampara College remember him as an average student who was more interested politics than his studies. The worried father, who desired his son to enter the civil service like him, put him at Valvai Educational Institute, a private tutory to receive additional instruction. At that time Pirapaharan was in his eighth standard and was 14 years old. There Pirapaharan fell under the influence of the Tamil Language teacher, Venugopal, a long standing activist of the Federal Party Youth League, who quit it saying that it was not militant enough. Venugopal teamed up with a Federal Party parliamentarian who formed the radical “Suyadchi Kalazham,” Self Rule Party, after he was sacked from his party.

Venugobal influenced Pirapaharan vastly. Pirapaharan admits:

It is he who impressed on me the need for armed struggle and persuaded me to put my trust in it. My village used to face military repression daily. He used to talk to us on the various world movements, how nothing can be accomplished by parliamentary means, etc. I was 14 years old then and my feeling that we also should hit back was reinforced. We were also convinced that we should have a separate state.

Next: Chapter 2: Going in for a Revolver

###

Index to Volumes 1 & 2