by T. Sabaratnam, 2003

Volume 1, Chapter 1

Original index of series

Original Chapter 2

Conviction Reinforced

Venugobal master’s arguments that parliamentary democratic methods would yield no result reinforced Pirapaharan’s childhood conviction that hitting back is the only option available to the Tamils. The 14–year boy placed his trust on armed struggle and the separate state.

P. Venugobal’s arguments were twofold. The first demonstrated that Tamils, though a minority, are a distinct nation enjoying all the elements needed for nationhood – a separate identity with a distinctive language, religion, history and culture, living in a separate territory and with a burning desire and firm will to preserve their identity. The will to preserve their identity Tamils had demonstrated from ancient times by resisting Sinhala intrusion into their territory whenever it occurred and by expelling conquerors at the earliest opportunity. At times, they had also fought with their southern Sinhala neighbours and expanded their territory.

The second argument of Venugopal’s held that the parliamentary democratic means adopted by the Tamil leadership to win Tamil rights had failed and armed struggle was the only available option.

Venugobal had also told his class that Sri Lanka provided a classic example of how a unitary state structure imposed on a pluralist society helps the ethnic majority to consolidate its own position and aids it to subjugate the minority ethnic community. The Sinhalese, the ethnic majority, had made use of its numerical superiority to suppress minority Tamils.

James Velupillai Chelvanayakam

The Sinhalese suppressed the Tamils by encroaching on their land through state-aided colonization and by reducing their voting strength, and thus their share in government, by disfranchising nearly a million Indian Tamils by depriving them of their citizenship. The Sinhalese then marginalized the Tamils by denying their language, Tamil, official status and requiring the Tamils to learn Sinhalese, the only official language, to obtain government employment.

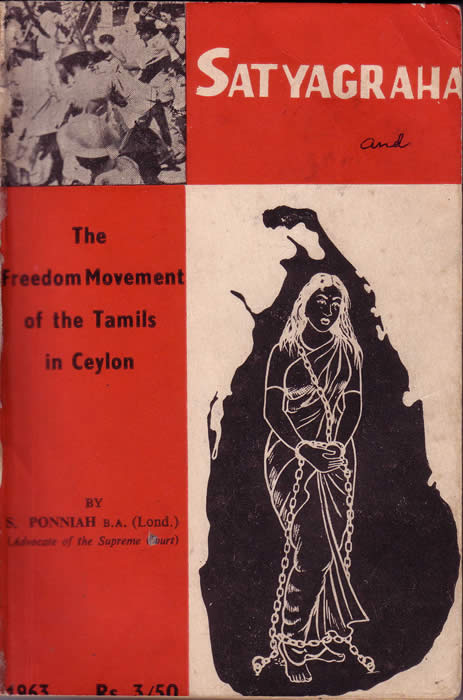

The Tamils naturally resisted. Their resistance was suppressed by the use of mob violence and the armed might of the state. The first show of Tamil protest – the 1956 Galle Face satyagraha- was disrupted by organized Sinhala hoodlums, denying forever to the Tamils the freedom to stage non-violent protests in Sinhala majority areas, including the country’s capital, Colombo. Defiance would be dealt by Sinhala mob.

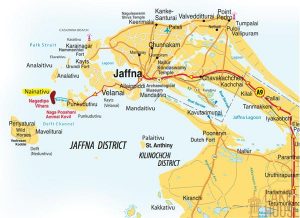

The denial of the right of peaceful public protest was extended five years later, in 1961, to include the Tamil majority northern and eastern provinces by the use of armed power of the state. In that year, the Federal Party, led by the Gandhian Samuel James Velupillai Chelvanayakam, launched a peaceful protest against the implementation of the Sinhala Only Act. The satyagrahis prevented Tamil officers from working in Sinhalese by blocking them from entering the five main government secretariats in the Tamil majority provinces. The Federal Party leaders and volunteers sat in front of the gates of the secretariats in Jaffna, Vavuniya, Mannar, Trincomalee and Batticaloa and prevented officers from entering their offices to work in Sinhala. The government clamped down with emergency rule, imposed curfew, used the army to break up the protest and detained the Tamil leaders.

Mr. Chelvanayakam participating in a Satygaraha campaign in Trincomalee in 1961, with ( R-L) Mr. Thambiah Ehambaram ( Muttur MP) & Mr. N.R.Rajavarothiam ( Trincomalee MP).

The avenue of extra-parliamentary peaceful protest was thus denied to the Tamil people. The use of parliament itself as a forum to take forward their campaign for Tamil rights had totally failed. The two agreements the Federal Party leaders had worked out with two Prime Ministers were not honoured. The 1957 Bandaranaike- Chelvanayakam Pact was abandoned by Bandaranaike the next year when a group of Buddhist priests sat opposite his residence demanding that the document he signed with Chelvanayakam be torn to pieces in their presence. The Prime Minister obeyed. He brought the original document he and Chelvanayakam signed and tore it to pieces. Chelvanayakam’s 1965 Agreement with Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake had a similar fate. Three years after signing Senanayake told Chelvanayakam that he was not in a position to implement it due to opposition by the Buddhist clergy.

The parliamentary numbers game Chelvanayakam played between 1960 and 1968 in which he used his party’s strength in parliament to break and make governments also failed to advance the cause of Tamil rights. In April 1960 Chelvanayakam joined the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) to vote Dudley Senanayake’s government out of office on the assurance that Tamil grievances would be addressed if the SLFP came to power. When it came to power in July, 1960, the SLFP’s new leader, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, refused to honour that promise. She implemented the Sinhala Only law with vigour. In 1965, Chelvanayakam switched sides. He signed an agreement with Dudley Senanayake and joined his government. He was let down again.

Venugobal analysed all these events and told his students that parliamentary politics and pious non-violence would not produce results. “Parliamentary democracy has not solved ethnic conflicts anywhere in the world,” he told his pupils. He demonstrated with examples from history that armed struggles had succeeded where parliamentary democratic process had failed.

The Time Bomb

Pirapaharan had seen army excess since childhood . In Valvettithurai, his village, it was a cas e of daily military repression; roundups, searches, extortion, arrests and torture. People hated the army. Children detested soldiers. Pirapaharan has said in interviews that he grew up in an environment that loathed the army. He himself abhorred the army.

e of daily military repression; roundups, searches, extortion, arrests and torture. People hated the army. Children detested soldiers. Pirapaharan has said in interviews that he grew up in an environment that loathed the army. He himself abhorred the army.

Pirapaharan was six years when, on April 19, the army fired and wounded three youths at Valvettithurai and killed one and injured two at Point Pedro. Youths inflamed by the arrest of Federal Party leaders the previous day had thrown stones at an army night patrol. The soldiers shot at the stone-throwers. Pirapaharan joined a group of agitated youths who visited the houses of the wounded youths.

In Valvettithurai, children invented a new game to replace the traditional cop and robber game. In their game guerrillas armed with air guns tucked under the waist bands of their shorts would wait hidden to spring and attack soldiers. Pirapaharan played the game with his friends, always taking the role of the guerrilla leader. He selected the hideouts, conducted the training and led the assault group.

Pirabaharan’s hatred of the army deepened after he came under the influence of Venugobal. He became politically active. He attended political meetings and met the Federal Party youth leaders. He discussed the plight of the Tamil people which always ended with his query, “Can’t we hit back?”

His classmates recall his telling the stories of Sinhala atrocities he heard from the elders. He also told them about the political meetings he attended and about Amirthalingam’s strident call to build Tamil resistance.

“Pirapaharan was then reading a book containing the speeches of Swami Vivekananda. He showed the book to us and talked about his appeal to Hindu youth to rise and work for the revival of Hinduism. Knowing his attachment to Variyar,” his classmate now residing in Australia said, “we teased him: Are you going to follow Swami Vivekananda? He said: No. I am more interested in the plight of the Tamils. We must first put an end to army oppression.”

“Pirapaharan was then reading a book containing the speeches of Swami Vivekananda. He showed the book to us and talked about his appeal to Hindu youth to rise and work for the revival of Hinduism. Knowing his attachment to Variyar,” his classmate now residing in Australia said, “we teased him: Are you going to follow Swami Vivekananda? He said: No. I am more interested in the plight of the Tamils. We must first put an end to army oppression.”

They then used to talk about army atrocities and the need to fight them back. “You cannot go and sit and shout slogans. They will hit you. You must fight back. Then only they will stop hitting,” Pirapaharan argued and others agreed. They also agreed that they needed arms to fight the army.

They decided to experiment making bombs. Pirapaharan opted for time bombs because exploding them would be less risky. They first experimented with the chemicals packed in firecrackers. Then, they tried with the chemicals pilfered from the school lab. They filled empty soda bottles with chemicals and closed them with a cork. They inserted an incense stick through the cork.

His classmate now living in Australia recalls: “We decided to explode the time bomb during the lunch interval. We waited until other boys finished using the toilet. We waited outside. Pirapaharan and another boy took the time bomb, placed it inside the toilet, and lighted the incense stick. We waited with bated breath. Nothing happened. Losing patience Pirapaharan wanted to go and find out whether the incense stick was burning. Others prevented him. Then the time bomb exploded.

“We all burst out laughing. We were all thrilled. Just then, someone in our group whispered, ‘Principal.’ We rushed back to our class.”

The Principal went to the toilet. He inspected the place and walked straight to Pirapaharan’s class. He knew that that must be the class that would have done it because students of that class attended the Valvai Tutory. People of Valvettithurai knew that Venugobal master was preaching armed struggle.

The Principal said sternly, “Who did it. Tell me who did it?”

There was deafening silence. None spoke. The Principal was an understanding person. He was aware of the emerging situation. Revolt was brewing in young minds. He did not press hard.

“Alright. Keep these things outside school,” he said and left the classroom.

Pirapaharan kept his preparations to battle the army outside school from then on. He and his schoolmates learnt the basics of karate and judo. They learnt to condition their bodies to endure prolonged suffering and deprivation. They would tie themselves up inside sacks and lie in the sun the entire day. They would lie on chili bags. They would prick their nails with pins. Those were the acts of torture the police and army then employed.

“We are freedom fighters,” Pirapaharan boasted to his friends, “and we must be psychologically equipped to withstand torture.”

Going for a Pistol

Seven of his friends were as eager as he was to fight back the army. They took part in training and in the manufacture of bombs. They formed themselves into a small group. They did not bother to find a name. They had only one objective: to fight the police and the army, the armed instruments of the oppressive state.

Pirapaharan told them that the pious formulation of an objective would not suffice. One must have arms to fight, at least a pistol or a revolver. They had seen those weapons in the hands of the police and some elders. None of them had ever touched one. They decided to buy at least one weapon. To buy one they needed money. They decided to float a fund. They decided to contribute 25 cents a week from their pocket money.

Pirapaharan was the president, secretary and treasurer of the group. Others considered him trustworthy. He kept the money. In 20 weeks, that nameless, secret group had amassed forty rupees.

With that treasure, they decided to look for a pistol. They heard a chandiyan (village thug), Sambanthan of Point Pedro, wanted to sell his pistol for Rs. 150. The group decided to buy it. Pirapaharan sold the ring he had received as a present during his elder sister, Jagatheeswari’s, wedding for Rs. 70. They were still short by Rs. 40. Pirapaharan said he would persuade the chandiyan to either reduce the price, recognizing the patriotic nature of their mission, or agree to accept the balance of the money later.

One morning Pirapaharan and one of his friends left for Point Pedro by bus and met Sambanthan ,who was puzzled to see two schoolboys in shorts asking for the pistol. His first reaction was to chase them away. However, their eagerness to see the weapon made him show them the pistol. He allowed them to have a look, taking care not to permit them to touch it.

“This is not a play gun. You children should not even touch it,” he told them.

Pirapaharan who had seen a pistol at close range for the first time was in tears when he was told not to touch it. He begged the thug to show him how to operate it. The thug declined, saying that was not a weapon for boys. He then asked why they wanted it.

Pirapaharan proudly proclaimed that they needed it to fight the police and the army.

“We must drive them away, these instruments of Sinhalese oppression,” Pirapaharan thundered.

“Why?’’ Sambanthan demanded.

“To win the Tamil nation its freedom,” Pirapaharan replied proudly.

Sambanthan was bewildered. He told them not to talk above their age and advised them to concentrate on their studies.

“There are leaders to look after these matters. You had better study now. After growing as big like me you can think of those things. Now go.”

Pirapaharan was not prepared to go. He asked, “Will you sell it to us if we bring the balance money?”

Sambanthan said he would not do so and Pirapaharan returned crestfallen.

In the Velicham interview Pirapaharan recalled that event thus:

I was a fourteen- year school boy and with seven like minded youngsters at our school we decided to form a movement with no name. Our aim was to struggle for freedom and to attack the army. I was the leader of the movement. At the time the idea that dominated our minds was somehow to buy a weapon and to make a bomb. Every week the others would give me 25 cents they had saved from their pocket money.

I maintained this pool of savings till we had accumulated Rs.40/-. At this time we learned that a ‘Chandiyan’ (thug) in the neighbouring village had a revolver which he was prepared to sell for Rs.150/-. Determined to buy this revolver somehow, I sold a ring which had been presented to me during my sister’s wedding. It fetched Rs.70/-. Altogether we now had Rs.110/-. We had then to abandon our plan to buy this revolver as we couldn’t find the balance of the money.

Sambanthan was not the only person who rebuffed him. A former teacher at Chidambara College, now in his eighties, recalls, “Pirapaharan’s class had become noted. I remember some teachers talking about the class and saying they had warned the class. I don’t remember anyone singling out Pirapaharan.”

Pirapaharan lost his interest in education by the time he reached GCE (OL). He was more involved in politics. He attended political meetings and discussion groups.

He attended the Federal Party’s Eleventh Annual Convention held at Uduvil during April 7-9, 1969 at which Chelvanayakam admitted the failure of his policy of cooperating with the Sinhalese in an effort to get them to solve the Tamil problem. Chelvanayakam told the convention:

Since 1960, we experimented with a new strategy of cooperation with the major Sinhala parties. First, we supported the SLFP in March 1960 to defeat the UNP because the SLFP came to an agreement with us. But the SLFP failed to honour that agreement. In 1965, we entered into an agreement with the UNP which promised to do some things for the Tamils. Now they too have let us down.

Shorts-wearing Pirapaharan was with the group of youths who mooted a resolution calling for the establishment of a separate state for the Tamils. They argued that since both the major Sinhala parties – the UNP and the SLFP had let down the Tamils, the only option left for the Tamils was a separate state. The Federal Party leadership persuaded the youths to drop the resolution at this convention.

The press questioned Chelvanayakam about the youths’ proposal. He was asked, “The Sinhalese call you federalists, separatists. But you persuade the youth to drop their separatist demand. Why did you reject the separatist demand?” His answer was, “We did not reject it. We only told them: Give us some more time. We will try and persuade the Sinhala leaders to call us by the correct name – federalists – and make them realize that federalism is an instrument of unity and not separation. They [the youth] have agreed to give us that time.”

Chelvanayakam was asked, “What will happen if you fail to persuade the Sinhala leaders?” His answer was, “If we old people fail, youth will triumph.”

In May Education Minister I. M. R. A. Irriyagolla provoked Tamil youths by ordering the three Tamil schools started by Harijans who embraced Buddhism and to be run as Sinhala Buddhist schools. He announced that he would be present at the takeover ceremony. Tamil youths took that as a challenge and commenced recruitment of volunteers to stage a massive satyagraha campaign. Federal Party persuaded Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake to defuse the tension by canceling the takeover of the schools.

The Federal Party Youth Front, determined to show its opposition, organized a protest march, but the police refused permission. The Youth Front announced its decision to defy the ban. The government deployed the navy to reinforce the police protection afforded to the three schools. The Federal Party intervened and dissuaded the youth from clashing with the navy.

The Federal Party’s dilatory tactics caused immense heartburn among Tamil youths. Many groups broke away from the party and one such group was called the Kuttimani – Thangathurai group. Both Kuttimani and Thangathurai were from Valvettithurai. Kuttimani’s real name was Selvarajah Yogachandran. Nadarajah Thangavelu was the real name of Thangathurai. In 1969, they organized a meeting in Jaffna. The group voiced its frustrations with the activities of the Federal Party and decided to organize an armed struggle. Thangathurai, an admirer of Yasser Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization, wanted to name the new organization the Tamil Liberation Organizaton (TLO), but no final decision was made. The group decided to leap into armed struggle.

The group held its regular meetings in a spacious private residence in Point Pedro. Pirapaharan attended those meetings. He was the youngest of those in the group. He was 14-years old. Besides Kuttimani and Thangathurai, Periya Sothi, Sinna Sothi, Chelliah Thanabalasingham (Chetti), Chelliah Patmnathan (Kannady), Sri Sabaratnam, Ponnuthurai Sivakumaran, and Vaithilingam Nadesuthasan also attended the meetings.

“We did talk about revolutions. We also talked about revolutionaries. But we talked more about making bombs and collecting arms… We were a small group, about 15 in all,” Nadesuthasan has recalled to a Tamil magazine.

In 1971 and in 1972, while the group was making explosives inside a palmyrah grove in Thondamanaru bombs went off injuring many members. Pirapaharan got a severe burn injury in his leg which left a black scar.

Next – Chapter 3: The Unexpected Explosion

###

Index to Volumes 1 & 2