by T. Sabaratnam, August 2003

Volume 1, Chapter 4

Original index of series

Original Volume 1, Chapter 5

Chapter 5: Tamil Youths Turn Assertive

Tamils – a subject race

Amirthalingam’s Kankesanthurai speech was a reflection of the growing feeling of frustration among Tamil youth. The youth were telling the leaders to follow the path of the JVP and the Awami League.

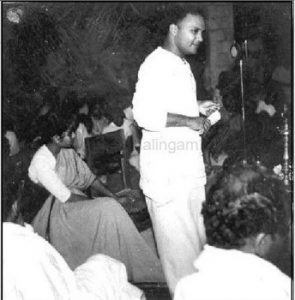

Appapillai Amirthalingam

The JVP revolt and Bangladesh liberation had emboldened them. They realized that the constitution makers were primarily concerned with the consolidation of the power of the Sinhalese and were insensitive to the feelings of the Tamils. The draft of the new constitution then under preparation contained provisions to entrench the unitary character of the state, the official language status for Sinhala and foremost place for Buddhism. Taken together, the three provisions would make Sri Lanka a Sinhala country and make Tamils a subject race.

The youths wanted to resist. They were confident they could mobilize the people, as had been done in Bangladesh. They turned more active and assertive. They said Tamils should unite and the leaders should show the way. What Amirthlingam said in Kankesanthurai was what the youths were saying: hard struggle, and, if necessary, bloody struggle and Tamil unity.

Sinhala journalists, who equate Sinhala interests with Sri Lanka’s, took Amirthalingam to task and accused him of being unpatriotic. Sun, then the leading and most chauvinistic of the Sinhalese-controlled newspapers, tried to show that the views expressed by Amirthalingam was personal and did not represent the collective view of the Federal Party. Yet Amirthalingam’s views had to be given cognizance in view of India’s action in Bangladesh, the newspaper editorialized. What the Sun and Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s government failed to comprehend was Amirthalingam’s views represented the overall view of the Tamil youths.

The government ordered Jaffna police to make inquiries. The police recorded statements from several persons who attended the Kankesanthurai meeting. The government unleashed a virulent campaign against Amirthalingam. It called him unpatriotic. It called him double-tongued; saying one thing in the south and a different thing in Jaffna. The youths too started a campaign against Amirthalingam. They accused him of being too soft.

Youths criticized the Federal Party leaders severely at the special convention held in Jaffna on 30 January 1972 to consider the draft constitution prepared by the Steering and Subjects Committee. They told their leaders that Sinhala leaders would never give the Tamils their rights and not to go begging behind these leaders. They called the draft constitution a Charter of Slavery and urged the Convention to reject it. Leaders of the Federal Party obeyed. They called the draft constitution a Charter of Slavery and passed a resolution rejecting it.

The resolution at its tail end attached a 4-point demand which said:

- The status accorded to Sinhalese should be accorded to Tamil.

- The country should be declared a secular state.

- Citizenship should be given to all persons who make Sri Lanka his or her home.

- Tamils should be allowed to rule themselves in their traditional homeland.

Youths mocked the 4-point demand. They said their leaders were asking for the very things the draft constitution had rejected. “These old lawyers cannot abandon their habit easily,” they said. The youths decided to go directly to the people. They organized public meetings and rallies in every electorate. Then they took the agitation to the villages. They held street demonstrations and meetings and told the people that the Sinhalese want to make them slaves and asked them to get ready to fight back.

Leaders fall in line

Leaders fell in line with the emotional wave generated by the youth. They took two steps to build support for a separatist struggle. The first was to whip up Tamil Nadu’s support. Thanthai Chelva and Amirthalingam went on 20 February 1972 to Tamil Nadu to mobilize the support of Tamil Nadu leaders. They met Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Muthuvel Karunanithi, Education Minister V. R. Nedunchcheliyan, former chief minister M. Baktavatchalam, Diravida Kalazham leader Periyar E. V. Ramasamy Nayakar, president of the Indian National Congress K. Kamaraj, Thamilar Kalazham leader M. P. Sivagnanam and Muslim League leader Kayithe Millath.

Kovai Mahesan (at extreme right) with SJV Chelvanayagam & Mr. A. Amirthalingam (on extreme left) and Mrs. M. Amirthalingam visiting CN Annadurai’s house in 1972. Other personalities seen in the photo are A.P. Janarthanam (student leader of DMK, and later affiliated with MGR’s Anna DMK) and A.S. Manavaithambi (Indian Tamil leader in Sri Lanka, who later returned to India).

Thanthai Chelva told them that Sinhala leadership was trying to make them slaves and were thus forcing them to ask for a separate state. Thanthai Chelvai told them the Tamils’ struggle for a separate state would be non-violent. He told Kamaraj of his experiences during the 1961 satyagraha and Kamaraj; shared his experiences during the Indian independence struggle. Periyar was the only one who struck a discordant note. “Will non-violence work with people who do not value the moral force?’ he questioned. Thanthai Chelva could not give a proper answer. He said: “Moral force will ultimately triumph.”

Tamil Nadu politicians pledged moral support and undertook to brief Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. At the civic reception Chennai mayor, Kamadchi Jayaraman said people of Tamil Nadu were with the Ceylon Tamils in their struggle. Thanthai Chelva assured them that the struggle would be nonviolent and their moral support is the only thing the Sri Lankan Tamils sought.

Three months later, on May 14, Thanthai Chelva took the next step to prepare the people for the struggle. He convened on that day a meeting of Tamil leaders and prominent Tamils in Trincomalee Town Hall. Leaders of the Federal Party, All Ceylon Tamil Congress, Ceylon Workers Congress, Eelath Thamilar Otrumai Munnani, All Ceylon Tamil Conference, representatives of several linguistic trade unions, students’ movements and non-party workers attended the meeting.

Ceylon Workers Congress leader S. Thondaman who attended the meeting said their decision to form the Tamil United Front (TUF) had an electrifying effect on the entire Tamil community. Thondaman, whose trade union had kept aloof from the agitations of Ceylon Tamils, told the meeting that the new constitution had brought about a “new situation that required new remedies.” Thanthai Chelva said, “Tamils should unite to oppose the “one-sided constitution.”

The TUF decided;

- To reject the new constitution;

- To boycott the ceremonial opening of Parliament which had been renamed the National State Assembly;

- To observe May 22, the day the new constitution is to be proclaimed, as a day of mourning; and

- To place before the Government a six-point demand and to call it to amend the constitution to accommodate the aspiration of the Tamils within a period of three months, ending in September 1972.

The six-point demand read:

- The Tamil language should be given the same status as Sinhala in the constitution.

- There should be constitutional guarantees of full citizenship to all the Tamil- speaking people who had made this country their home. There should not be different categories of citizenship or discrimination against some of them. The state should have no power to deprive any citizen of his citizenship.

- The state should be secular, with equal protection accorded to all religions.

- The state should ensure valid fundamental rights guaranteeing equality of persons and ethno-cultural groups.

- There should be a provision in the constitution for the abolition of caste and untouchability.

- In a democratic and socialist society, only a decentralized structure of government would make for a participatory democracy with people’s power rather than state power.

The letter embodying the six-point demand said that, if the government failed to take meaningful steps to amend the constitution within three months ending on 30 September 1972, the TUF would launch a non-violent struggle to win back the freedom and rights of the Tamil people.

The constitution was promulgated on 22 May 1972 and 15 of the 20 Tamil Members of parliament boycotted the ceremony. The five members who attended the ceremony and voted for the 1972 constitution were: C Arulampalam (Nallur), A Thaigarajah (Vaddukoddai), of the Tamil Congress, C X Martyn (Jaffna) who was expelled from the Federal Party, M C Subramaniam and Post and Telecommunications Minister C Kumarasuriar, both nominated members.

The Tamils in the North and East observed that day as a day of mourning and observed a dawn to dusk hartal. Youths took to the street, waving black flags. They ensured that all shops were closed and brought transport to a standstill. Students boycotted schools the previous day as May 22 had been declared a public holiday. The hartal was total. People defied the government ban on rallies and meetings, gathered in the evening at street corners, and burnt the Sri Lankan flag and copies of the constitution. Youth speakers told the crowd that Tamils had been pushed to the wall, Sinhala-Tamil relations had reached the breaking point, and the only way out for them was the Bangladeshi way.

TUF leaders who did not want to defy the ban on public meetings imposed by the government using emergency regulations held their protest convention indoors at the Navalar Archiramam, Vannarponnai, Jaffna. Thanthai Chelva declared:

We wanted to live united. We wanted to live as dignified, respected partners. That has been denied to us. They want us to be their slaves. No man with self- respect will accede. We want to live with self- respect. If that can only be done through separation, then we will have to travel that path. I wish to declare to my people and the world that we are being compelled to travel that path.

Seeds of violence

Republic Day for the Tamils was a dark day. The previous night militant youths tampered with a high-tension electric tower in Jaffna and caused a total blackout. Republic Day celebrations were confined to Jaffna Secretariat, the police stations and the army and naval camps. The public had separated themselves from independence and the Sinhala government.

There were sporadic incidents of violence throughout the North and Eastern provinces. Buses were torched, government buildings stoned and black flags hung everywhere; on houses, public buildings and trees. Police went around Jaffna town in the morning and tore off some black flags. Six days later, on 28 May, militant youths threw hand bombs at the house of an LSSP supporter, Sivasothy, but no one was hurt. On June 1, hand bombs were flung at the residence of A. Viswanathan, the LSSP’s Jaffna organizer. Those incidents were an exhibition of the anger against the Constitutional Affairs Minister Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, deputy leader of the LSSP. Dr. de Silva had earlier been a champion of equal rights for the Tamils.

Militants then turned their anger towards the five Tamil parliamentarians who voted for the 1972 constitution and their supporters.There were four small armed groups in 1972.

The Thangathurai-Kuttimani group selected C. Arulampalam as their first target. ‘Small,” as Arulambalam was called because of his diminutive build, stayed in Colombo and thus beyond their reach. They decided to kill his supporter, V. Kumarakulasingham, former chairman of the Nallur Village Council, a strong SLFP supporter and a common friend of Arulampalam and Kumarasuriyar. It was Kumarakulasingham whom Kumarasuriyar used to induce Arulambalam to defect from the Tamil Congress to the government. Arulambalam had been declared a traitor by Tamil leaders and the militants since his defection.

Kuttimani, Chetti and Sri Sabaratnam walked up to Kopay junction on 4 June, 13 days after the promulgation of the 1972 Republican Constitution, and hired the taxi driven by Ulaganathan to go to Kumarakulasingham’s house. When the taxi was traveling on a lonely stretch of the road, they ordered the driver to stop. They got down, pulled the driver out of his seat, tied him up and put him in the car’s boot. Kuttimani drove the car to Kumarakulasingham’s house, shot him with his pistol and ran back to the car. The shots injured Kumarakulasingham in his legs. Kuttimani drove the car towards Neerveli, stopped the car on a lonely spot, shot and killed Ulaganathan and burnt the car along with him.

Kuttimani wanted to kill Kumarakulasingham, but killed the driver Ulaganathan. On the same evening hand-bombs were thrown at the residence of an SLFP supporter, Sundaradas. Sivakumaran’s attacks on the vehicles of Somaweera Chandrasiri in 1970 and Alfred Duraiappah in 1971, and the Thangathurai- Kuttimani group’s three bomb throwing attacks and Ulaganathan’s murder shook the conservative and peace-enjoying Jaffna and activated the other two armed groups, one headed by Pirapaharan and the other within the Tamil Student’s Union (TSU).

Not to be outdone by the Thangathurai- Kuttimani group and the Sivakumaran group, the TSU group headed by Sathiyaseelan acted fast. It sent a two-member assault group comprising Tissaveerasingham and Jeevarajah, known as Jeevan, to assassinate Vaddukoddai Member of Parliament ,Thiyagarajah, who had voted for the 1972 constitution. Both traveled to Bambalapitiya in Colombo where Thiyarajah lived. They went to his house in the morning of June 7 and knocked at the door. Thiyagarajah came out.

They told him the name of a Jaffna newspaper and announced that they had come to interview him.

“Kumarasuriyar had told me not to give any interview to any paper,” Thiyagarajah said and asked them to take their seat.

Tissaveerasingham did not sit. He stood close to Thiyagarajah, who was also standing. Jeevarajah stood by the door leaning on it.

Thiyagarajah, an experienced former principal of Karainagar Hindu College,

observed the nervous behaviour of the two visitors. He felt suspicious. Jeevarajah pulled out the revolver he had tucked in his trouser belt. He was nervous to fire. He was inexperienced. He was not sure whether the revolver would fire. He was also not certain about his aim. The revolver was of local manufacture and he had had minimal practice.

“Sudada”, (Shoot) Tissaveerasingham, who lost his patience, shouted.

“Tissai,” Jeevarajah shouted back signaling him to move away and he ran towards the door.

Thiyagarah acted fast. He bent down and pulled the carpet.

Jeevarajah lost his balance when the revolver fired.

Bullets struck the wall and Thiyagarajah escaped unhurt, The assailants fled.

Their assassination attempt failed, but it sent the necessary message to government supporters and the public.

Tamil Leaders Backtrack

Sirimavo Bandaranaike and the Tamil leaders failed to realize the importance and the pattern behind the acts of violence indulged in by the armed groups. Both sides viewed these acts of violence as sporadic incidents. Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s government thought that the police would curb the violence and Tamil leaders thought that Thalapathy (Commander) Amirthalingam would tackle the revolting youths. Amirthalingam. too, had given the TUF Action Committee that impression. “I can manage them,” was what he told the other leaders.

Police commenced the arrest of youth leaders from May 18, four days before Republic Day. Thambithurai Muthukuarasamy, founder member of the TSU, was arrested on that day. K Sivanandan and Sivajeyam were arrested on June 9, Namasivayam Anandavinayagam on June 10 and Kasi Ananthan on June 15. Mylvaganam Rajakulasuriar was arrested on June 30, M Sinniah Kuventhirarajah on July 9 and N Amerasingam July 12. Chelliah Thanabalasingham (Chetti) and Ponnuthurai Sivakumaran were also arrested. These arrests angered the youths and their protest spread.

Amirthalingam had misjudged the mood of the youths. That became evident on the question of taking the oath of allegiance under the 1972 constitution. Youths told TUF parliamentarians to boycott parliament. Their logic was simple. They told Tamil leaders that their decision when they inaugurated the TUF was to reject the new constitution; to boycott the ceremonial opening of Parliament; to observe May 22 as a day of mourning; and to present to the Government the six-point demand calling for the amendment of the constitution. “Now what are you going to do?” they asked. “You are going to accept the very constitution you rejected and asked the people to burn.”

On Jaffna’s Old Park Road appeared a telling scribbling in Tamil which meant: ‘Cheating is now the game.’

Youth protests did not deter TUF parliamentarians from swearing on 4 July in the National State Assembly. They swore: “I … do solemnly affirm/swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to the Republic of Sri Lanka and that I will well and truly serve the Republic of Sri Lanka and duly and faithfully execute the duties of my office as … in accordance with the constitution and with the law.”

The government showed to the international community the oath taking by Tamil parliamentarians as a victory and launched a campaign to show that Tamils had accepted the constitution. This angered the youths. They accused the parliamentarians of lending legitimacy to the constitution and asked them to stop attending the National State Assembly. The youth argued that the 1972 constitution had closed all avenues for further democratic solutions to the Tamil problems and the only option left was separation. They also urged that separation could be achieved through armed revolt, and they began to pressurize Tamil parliamentarians to quit and launch a mass liberation struggle.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike played into their hands. She did not respond to Thanthai Chelva’s letter containing the six-point demand. Thanthai Chelva sent a reminder. The Prime Minister’s office acknowledged the receipt of both letters. There was no talk about amending the constitution to accommodate the six-point demand. This gave room to the youths to tell the TUF to launch the non-violent struggle to win back the freedoms and rights of the Tamil people after September 30.

Tamil leaders were reluctant, but not the youths. Pirapaharan, then 17 years old, led a bomb attack on 17 September on the carnival held at the Duraiappah Stadium. That was to show their protest against police arrests of youths and, most importantly, to issue a warning against the government and Tamil leaders. He chose to attack the carnival because it was patronized by the police and army personnel. No one was injured.

On 20 December the Thangathurai- Kuttimani group threw a hand-bomb at the house of SLFP organizer for Uduvil, S. Vinothan. Again, no one was injured. Due to the mass arrest of the youths by the police there was then a lull in violence until the assassination of Alfred Duraiappah, former mayor of Jaffna, on 27 July 1975, an interval of two years and seven months. During this time, most of the armed militants were either in prison or in Tamil Nadu.

Next: Chapter 6: Birth of Tamil New Tigers

Will be posted on: August 15, 2003