by T. Sabaratnam, October 8, 2004

Chapter 18

Original index to series

Original Chapter 19

In Lake House, there was jubilation when the story of the TULF satyagraha held in Jaffna on 25 July spread. The joy infected the Sinhala people as radio and television broadcast the news.

I was at the weekly press briefing at the Information Department when the story broke. State Minister Anandatissa de Alwis, the government spokesman, announced the story with glee. “This is the end of the road for the TULF,” he said. Then he added, “In these circumstances, doubts arise as to what useful purpose it will serve to negotiate with the TULF on the Tamil problem.”

Anandatissa de Alwis

I wrote the satyagraha story for the Daily News. I topped it with Anandatissa’s comment and packed it with the on-the-spot report our Jaffna correspondents had telephoned in. It was next morning’s lead with the banner: ‘End of the road for TULF.’

Lalith Athulathmudali sprang into action. He planted a story in the Daily News and the Sun. Quoting unidentified government sources, the story said the government does not know whether TULF participation in the All Party Conference would serve any useful purpose. ‘Whom do they represent?’ the story queried.

The Daily News and the Sun and almost all the Sinhala newspapers backed their stories with editorial comment. The burden of all the comments was that the TULF has to be buried. The Tamil people had rejected the party. The Sinhala people need not carry that burden. BURY IT.

The decision to question the credibility of the TULF was taken by Jayewardene. The reasoning behind the decision was: India and the international community were pressuring the government to negotiate with the TULF and work out a political solution to the Tamil problem. The TULF was insisting that the solution should be based on the Delhi proposals embodied in Annexure C. The government is not prepared to concede that much to the Tamils. The way to wriggle out of it was to show the world that the TULF had lost its base and did not represent the Tamil people. There was no purpose in negotiating with it.

Then the question with whom the government should negotiate remained. Jayewardene’s answer was that he need not negotiate with anybody. Why?

The Jaffna satyagraha had shown that the TULF did not represent the Tamil people. No purpose would be served by negotiating with a party which speaks for nobody but itself. And you need not negotiate with the ‘boys’ with the guns as they do not want anything less than Eelam, which demand the international community did not support. Further, no government with self-respect would talk to terrorists.

The result? The international pressure to negotiate with the Tamils would thus ease. India, in particular, will have no backing for its diplomatic pressure moves.

With no pressure for a political settlement, the reasoning went on, the government could adopt the position that all that it had to do was to address Tamil grievances. Jayewardene decided to do just that. And he decided that he would also be free to put down the Tamil armed rebellion militarily in the guise of eradicating terrorism.

The justification for the shift from talks to war ran like this: How could one talk with the community which had obviously withdrawn support from those representatives who were prepared to talk? The community seemed to have shifted its loyalty to the ‘boys.’ But the boys are only ready to talk with the gun. So, we the government, have no option. We have to talk in the same fashion.

Mervyn de Silva

The entire Sinhalese-controlled media went along with Jayewardene’s reasoning. Only one Sinhalese journalist, Mervyn de Silva of the Lanka Guardian, sensed the danger. In his news analysis, titled ‘Who buried the TULF?’ on 1 August 1984 issue he wrote: ‘How very short sighted and stupid.’

He warned that, by adopting this strategy, Jayewardene and his advisers were burying not only the TULF, but also the non-violent democratic option. He concluded his analysis thus: “The process of polarization is being completed. But to whose advantage? In line with whose strategy? History will provide the answer.”

History provided the answer. As Mervyn foresaw Tamil militancy benefited. Pirapaharan, who had matured into a keen political observer and military strategist, made use of the great opportunity Jayewardene created for the LTTE.

Jayewardene went ahead with his shortsighted political excursion regardless of Mervyn’s warning. He had his cheering squad: Athulathmudali, Anandatissa and Gamini Dissanayake. The APC from then onwards was tuned to address Tamil grievances and to make cosmetic changes in the system of government. The two committees – on the system of government and Tamil grievances – already set up on 9 May were made use of for this purpose.

Indira’s Appeal

Jayewardene visited Delhi on his way back from the US and UK. He met with Indira Gandhi. She told Jayewardene that there was no question of Indian invasion or military intervention in Sri Lanka. She told him that she had made that position clear to the TULF.

Then she appealed to Jayewardene to speed up the deliberations of the All Party Conference and told him of the Indian view that regional autonomy for the Sri Lanka Tamils is the best solution to their problem. Jayewardene told her that he was not in a position to provide such a solution, mainly due to the opposition from Sirimavo Bandaranaike. Indira Gandhi then urged him to consider setting up provincial councils. Jayewardene told her that even provincial councils would not be possible considering the present mood among the Sinhala people. “We will lose our entire base. We will lose everybody,” he told her.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike

Indira Gandhi told Jayawardene that her government desired that an early settlement be reached. Jayewardene, who was waiting for such an appeal, told Indira Gandhi that he, too, desired an early settlement, but progress was hindered by those engaged in violence in Sri Lanka. He told her the Sinhalese people were angry because of the terrorists living in Tamil Nadu, having training camps there and engaging in acts of terrorism.

Indira Gandhi denied that there were training camps in Tamil Nadu. She said more than 30,000 Sri Lankan Tamil refugees were living there and said camps have been established to look after them. Jayewardene told her that she might not be aware of the training camps and gave her documents and maps that gave detailed information of the sites, names of the armed group using them, the number of cadres trained in them and the names and ranks of the Indian instructors.

Indira Gandhi was surprised, but kept her cool. She told Jayewardene that she would look into the information he had provided her. She knew that the information Jayewardene provided was correct. Her only surprise was how he had obtained it.

Madras Cafe, a 2013 film about CIA compromising of Unnikrishnan

One of the first acts of Athulathmudali after he assumed the office of Minister of National Security was to infiltrate the armed groups and RAW. A Malayalee named Unnikrishnan was the Madras chief of RAW. He was bought over with the help of the CIA. Unnikrishnan supplied the Intelligence Unit of the Sri Lankan Police with detailed information including charts and maps. Cyril Herath, the then Deputy Inspector General (Intelligence), prepared the documents and maps for Jayewardene. Herath’s report had even the type of weapons used by the armed groups.

Jayewardene and Lalith Athulathmudali, who was also in Delhi during Jayewardene’s visit, adopted a hard stance during their meetings with the media. They maintained that the Tamil problem was an internal matter of Sri Lanka. They said it was mainly a terrorist problem. They also maintained that the military approach was an integral part of the political solution to the problem. Athulathmudali said, “The more you succeed in curbing terrorist activities, the better the chances you have for a political settlement.”

The Hindu, in an editorial that reflected the Indian position, argued that the Tamil problem was no longer an internal problem because over 30,000 Sri Lankan Tamils had fled to India as refugees. It maintained that it was not a terrorist problem. “It must be clarified that the phenomenon of militancy among the Tamil youth in Sri Lanka is primarily a political phenomenon reflecting the maturing of the crisis.”

Jayewardene Proposals

Nearly three weeks after his meeting with Indira Gandhi Jayewardene held the plenary meeting of the APC on 23 July. He said the discussions were getting deadlocked because of two irreconcilable positions. Some advocated “District Councils and no more” while others asked for “Regional Councils and no less,” he said. He said proposals that bridge these positions without harming the fundamental premise of each side had become a necessity. He then presented a memorandum setting out the proposal for a Second Chamber. The conference decided to consider the Second Chamber proposal and the reports of the two committees in the next sessions.

The SLFP summarily rejected the Second Chamber proposal. Sirimavo Bandaranaike said, “It’s not worth consideration.” The TULF reserved its final judgment. Amirthalingam’s initial reaction was negative. He said: I don’t think that the idea satisfies the aspirations of the Tamils.” The LSSP and CP favoured the creation of the Second Chamber, but insisted that it should directly reflect the views and interests of the different nationalities.

The Second Chamber was discussed for five days in the first fortnight of August. Premadasa presented the report of the Committee on System of Government on 17 August. He left the important question of the unit of devolution open. He asked the plenary to decide whether the unit should be the district council or the provincial council. The conference considered Premadasa’s report for four days.

Amirthalingam, in his statement on 21 August, rejected the District Council as the unit of devolution. He said security of life and property had become the major concern of the Tamil people. He said the army had shot and killed two farmers and wounded another at Kilinochchi the previous day. The army had destroyed property, killed innocent people and robbed valuables in Mannar the previous week. (Details of these incidents are in the next chapter.)

“The safety and security of the Tamil people could be ensured only by the preservation of the unity and integrity of their homeland,” he said. “The Tamil people,” he added, “should be enabled to exercise in their homeland political power, including the power over internal law and order, economic development, and land settlement in that area. The structural framework that will ensure these arrangements is contained in the proposals on autonomy submitted to the All Party Conference by the Ceylon Workers Congress. Any solution that does not embody these principles will never be acceptable to the Tamil people.”

Amirthalingam also rejected the Second Chamber proposals for two major reasons. Firstly, the Second Chamber proposal was built on the District Councils which had been made the basic national units. Secondly, the Second Chamber proposal was designed to consolidate and reinforce the process of centralized authority.

The purpose of the drafters of the Second Chamber proposal was just that. They wanted the Second Chamber to perform a decorative function. They designed it to serve the Sinhala interest by centralizing power instead of decentralizing it. The drafters wanted to mislead the international community into believing that the government had gone beyond the Development Councils, while in fact they had backtracked by concentrating more power in Sinhalese hands.

The purpose of the drafters of the Second Chamber proposal was just that. They wanted the Second Chamber to perform a decorative function. They designed it to serve the Sinhala interest by centralizing power instead of decentralizing it. The drafters wanted to mislead the international community into believing that the government had gone beyond the Development Councils, while in fact they had backtracked by concentrating more power in Sinhalese hands.

Jayewardene consulted the leaders of the delegations about the committee reports and his Second Chamber proposal on 21, 29 August and 1 and 3 September. On the last day, the leaders considered the unit of devolution.

Amirthalingam rejected both district and provincial councils and insisted on the regional council proposal. “If the regional council request is denied,” he warned, “then the TULF has no option but to carry on its struggle for the liberation of the Tamil people, for the preservation of the integrity of the traditional homeland and for justice and human rights by all non-violent means.” Kumar Ponnambalam and Thondaman backed the regional council demand.

The next session of the APC was held on 21 September. Jayewardene placed his report before the conference and adjourned the discussions for 30 September. The 8-page report summarized the progress achieved during the past eight months. Jayewardene announced consensus had been achieved in four areas. They were:

1. Giving increased power to grassroots level democratic organizations;

2. Ending of statelessness;

3. Terrorism in all its forms should be eradicated;

4. The setting up of a Second Chamber.

He indicated that the Second Chamber could have legislative power and the District Councils within a province could join to form a inter-district coordinating and collaboration unit.

Government supporters called it a breakthrough and a progress. The Daily News screamed that an advance had been made on the unit of devolution. The TULF was not happy.

Amirthalingam announced his disappointment on 30 September. He said, though District Councils were allowed to join, they remained the basic unit. Powers were devolved to them and not to the united structure. But he was careful not to reject the proposal altogether. He kept the door open for further negotiation. He announced firmly that the only solution Tamils would consider was “one Tamil linguistic unit” comprising the north and east.

Jayewardene adjourned the plenary to 15-16 November. But, contrary to his expectations violence escalated in September and October. (Details in next chapter). And it spread to the east.

The Trap

In early October, a surprise move was made. Rev. Dr. Rahula Thera announced that he was taking a top-level religious delegation to Chennai to meet the leaders of the Tamil militant groups. He sent a letter to the leaders of the Tamil groups indicating his decision to talk to them. He asked them to stop violence and all other unlawful acts and come forward for talks. The leaders of the militant groups looked at the invitation within suspicion, Pathmanabha later told me. “We suspected a trap.” He said they knew that Jayewardene was behind it.

Pathmanabha

Pathmanabha said they realized that the trap was to make them reject the invitation so that Jayawardene could tell the world that the armed groups had rejected the peace moves initiated by the Buddhist monks. “We realized that Jayewardene was trying to justify his military onslaught,” he said. The militant leaders knew that Rev. Rahula was the right hand man of Cyril Mathew, the Tamil baiter and the main organizer of the violence against the Tamil people…

Leaders of the TELO, EPRLF and EROS jointly decided to reject the invitation without stepping into the trap. So they wrote thus to Rev. Rahula Thera: We are sorry that we are not prepared to talk to a delegation of Buddhist priests. Talking to them is not going to bring a political solution to the Tamil problem.”

Pirapaharan replied to Rev. Rahula separately. He made use of that letter to attack the Jayewardene government’s position. This is the translation of the letter written in Tamil:

Venerable Sir,

You have invited the Tamil Eelam Freedom fighters for talks. You have indicated in your letter that you want to talk to us as a representative of the Sri Lankan government. In your letter, you have laid down a condition. You have asked us to give up violence, stop violating the law and come for talks. Your invitation looks funny.

We are not the perpetrators of violence. We are not engaged in terrorism. Our only desire is not to live in slavery. We want to live as free men. We also yearn to live in peace. We are carrying arms to liberate ourselves from the armed oppression of the state.

We are sorry that a venerable priest like you is willing to represent a regime that disgraces the Buddhist religion.

If you really desire peace, if you really value Buddhism and Buddhist dharmma, please persuade the repressive state to end its oppression.

Please note that we are not prepared to lay down arms till the slavery of our people is ended and they are allowed to live as free men and women.

We took up arms to break off the shackle of slavery and to make our people live in freedom, peace and safety.

We want peace. But we are not prepared to beg it from the government that you want to represent and get deceived. We are determined to win our freedom through armed struggle.

Signed: V. Pirapaharan,

Chairman, Central Committee.

Military Commander,

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

The Jayewardene administration was not deterred by the clever replies of the militant leaders. It launched a general propaganda campaign. It accused the militants of failure to respond to the appeal by respected Buddhist priests.

The Assassination

The TULF informed Indira Gandhi after the 30 September meeting that it had lost patience. It told Parthasarathy that they wanted to walk out of the APC. Parthasarathy told them that Indira Gandhi was aware of the problems and was considering other options available to India and the Tamils. Parthasarathy was with his advisors in his office in the South Block considering the other options when the news of the shooting of Indira Gandhi reached him.

North Block, South Block and Rashtrapati Bhawan, New Delhi

Indira Gandhi was killed on 31 October 1984 when she walked from her residence to her office in the same compound. She walked along the path that connected her residence and her office. The time was 8 a.m. She was going to give a television interview to an American journalist. Her security chief, Dinesh Bhatt, and five officers walked ahead of her. Her private secretary, R. K. Dhawan, was following her. She neared the two Sikh guards, Piyanth Singh, a sub-inspector, and Satwant Singh, a constable, standing guard behind a thicket. Piyanth Singh pulled out his revolver and fired at her. Satwant fired with his machine gun. She collapsed and died.

I left Lake House around 8.15 a.m. and went to the Colombo office of the Institute of Fundamental Studies. When I went in the receptionist, a Sinhala lady, asked me, “Do you know the happy news?” “I don’t know. What is it?” I asked. “Indira Gandhi was shot,” she said. I was dumbfounded. Recovering I asked, “Is she dead?” “She’s gone” was the reply.

This receptionist was not the only one who was relieved by Indira Gandhi’s death. Most of the Sinhala people were happy. Some soldiers danced on the streets. They taunted the mourning Tamils, asking ‘Amma Enge? Amma Enge?’ (Where is your mother? Where is your mother?) They all felt that the pressure on the Jayewardene government for a settlement of the Tamil problem had eased.

Ranil Wickremetunge (l.), Ravi Jayawardene (center)

Ravi conveyed the news to his father, President Jayewardene. A little later Lalith Athulathmudali telephoned Jayewardene and conveyed the news.

Indira Gandhi’s murder shook the Tamils of Sri Lanka. Many cried. Black and white flags were hoisted in private houses and public places. Shops pulled down their shutters. Schools closed. Transport screeched to a halt. The Tamil majority northeast mourned her death. Never since the death of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru had the Tamils of Sri Lanka sunk into such genuine grief. At least 12 girls born in Jaffna in the first five days of November were named Indira.

Tamil leaders issued condolence messages. They all called Gandhi “Mother Indira Gandhi.” They said her death was irreplaceable. Leaders of all the Tamil militant groups were in Chennai. They eulogized her, calling her Annai (Mother).

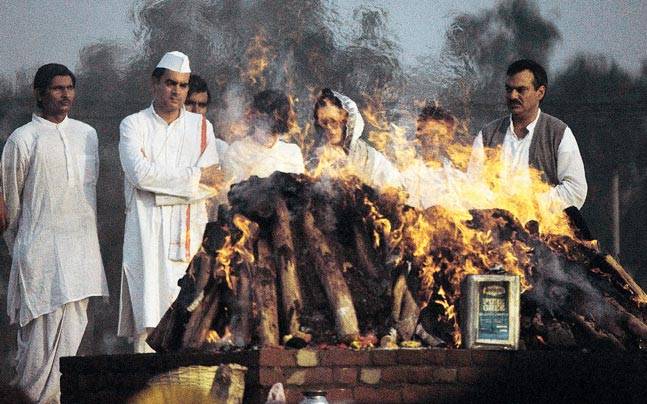

Indira Gandhi funeral pyre, October 31, 1984, photo courtesy India Today

Amirthalingam said her death had removed, “the only shield the Tamils had against the genocide”.

Tamil leaders sent condolence messages to her son Rajiv Gandhi who succeeded her as the Prime Minister. Amirthalingam sent a telegram to Rajiv. “The Sri Lankan people have lost their mother,” he said. In a press statement, he said that the Tamils who were in a state of uncertainty were now full of anxiety regarding their future in the absence of the slain leader. He told me, off the record, “The old man will now wriggle out of all his commitments.’

Pirapaharan sent a letter to Rajiv Gandhi. This is the translation of the letter he wrote in Tamil:

Honourable Rajiv Gandhi,

No.1 Subedar Jang Rd.

New Delhi.

Dear Sir,

We were deeply grieved and intensely shocked when we heard that Mother Indira Gandhi has been killed by wicked gunmen. We strongly condemn this despicable crime against humanity.

We have lost the beacon light, the source of inspiration of the oppressed people of the world, the most enlightened leader of India. We share the distress and grief your family, the people of India and the world suffer by this irreplaceable loss.

Mrs. Indira Gandhi toiled tirelessly for world peace, human dignity and freedom. She voiced the rights of the oppressed people. She slogged hard with vision and determination to develop India along a socialist path. She was the architect of the New India. She opposed with grit vicious imperialism and its intricate network. She backed national struggles for self-determination and freedom worldwide.

Mother Indira, always, showed sympathy, understanding and support to hapless, suffering and oppressed people of Tamil Eelam. She continuously condemned the Sri Lanka government’s denial of the basic rights of the Tamil people. She applied political and diplomatic pressure to compel the Sri Lankan government to end its program of genocide of the Tamil people. She took personal interest in forcing Sri Lanka to work out, with India’s mediation, an honourable political solution to the Tamil problem. She towered as the protector of the oppressed Sri Lankan Tamil people. If not for her personal interest, our community would have been wiped away. She was the epitome of the spiritual strength of the Tamil freedom struggle.

Tamil people will remember Indira Gandhi forever with love, respect and enduring gratitude. We firmly trust that you, who have succeeded her to the national and global leadership, will carry forward the ideals for which Mother Indira Gandhi lived, worked and died.

We wish you success.

With respect,

V. Pirapaharan,

Chairman, Central Committee,

Military Commander

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

The Sri Lankan government declared 3 November, the cremation day, a public holiday. Thousands of Sri Lankans, including Sinhalese, patiently lined up at Indian House, the official residence of the Indian High Commissioner, to sign the condolence book. In Jaffna, militants gave Indira Gandhi a ‘bomb salute.” The whole day they exploded bombs every half an hour.

Jayewardene attended Gandhi’s funeral. He had a brief meeting with Rajiv Gandhi. Jayewardene told him that Sri Lankan people were of the view that India was taking the side of the Tamils and was forcing his government to grant the demands of the TULF. Jayawardene assured that he would keep his commitment to make use of India’s good offices, but a fresh approach was needed. Rajiv Gandhi responded favourably.

Rajiv Gandhi told Jayewardene that he was willing to make a fresh start in Indian mediation efforts. He assured that India would move away from the partisan role it had been playing. He told Jayewardene of the need to work out a solution to the Tamil problem. He said the solution should meet the aspirations of the Tamil people. He warned that failure to do so would lead to prolonged conflict and to the dismemberment of the country. He assured Jayewardene of India’s commitment to the unity and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka.

On his return to Colombo Jayewardene told the media that his meeting with Rajiv Gandhi was fruitful. He said the “young prime minister was willing to make a fresh start” and had given him a “firm commitment not to support separation.” He briefed the cabinet of his assessment of the new prime minister. He said, “I feel that we could have a better relationship with Rajiv Gandhi.”

The talk in the Colombo grapevine was that Rajiv and the new Foreign Secretary Romesh Bhandari were novices who could be manipulated.

Jayewardene’s handling of the All Party Conference after Indira Gandhi’s death was based on that assessment. He postponed the meetings fixed for 14 November to 14 December, saying that the draft bills on the system of government were not ready. And on 14 December, he presented the draft legislation to the plenary and postponed it for 21 December. He asked the delegations to indicate their reactions on 21 December.

The draft legislation on the System of Government provided for a five-tier administrative framework. The five tiers were:

Grammodhya Mandalayas

There will be around 4500 Gramodhaya Mandalayas chosen from the people’s voluntary societies in the villages.

Pradesheeya Sabhas

These will be at the level of an Assistant Government Agent’s divisions as presently constituted and numbering around 250. They will be elected. Their functions will be mainly local governmental.

District Councils

The third tier will consist of District Councils, like the presently constituted Development Councils. The area of authority of a District Council will be an Administrative District. There will be 25 of them. In future too they will be elected and the Chairman and Vice chairman will be elected by the electors at an election of the Members of the Councils. Their powers and functions will be larger and wider than those exercised by a Development Council.

Provincial Councils (Inter-District Authorities)

Provincial Councils will be constituted for two or more administrative districts in a province, where the District Councils resolve to join and their decision is approved by the majority of the registered voters in each of these administrative districts. Provincial Councils will have such powers as are delegated to them by the District Councils. Provincial Councils will consist of all the members of the District Councils resolving to join.

Provincial and District Ministers

The President will have the power to appoint Members of Parliament or Members of the Council of State as Provincial Ministers or District Ministers. He may appoint a Provincial Chief Minister who is likely to command the confidence of a Provincial Council.

Council of States

There will be established a Council of State consisting of 75 members. Of these the Chairman and Vice Chairman of each District Council will number 50. There will also be 18 members, two members appointed from each province from among the members of those communities which are not represented or adequately represented in the District Councils established within that province. There will be seven members appointed by the President.

The functions of the Council will be mainly advisory. It will not have the power to delay any legislation passed by Parliament though it will have the power to initiate legislation and to communicate its opinions on bills affecting fundamental rights, language rights, regional rights, national unity and integrity etc. It can also set up Committees to inquire into inter-district and inter-provincial matters, questions of national unity or social and economic affairs.

It will also serve as a reservoir for the selection of ministers.

Athulathmudali, the conference spokesman, after distributing the documents – Jayewardene’s statement and the Objects and Reasons of the Proposed Legislation – told the media that the people would be consulted before the proposed legislation was placed before Parliament. Premadasa took it to the people the next day in his address to the UNP annual sessions. He demanded that the people be consulted in a referendum and asked them to consider whether the new arrangement posed a threat to the unitary character of the constitution.

Jayewardene, who spoke after Premadasa, answered the question. He said the new arrangements, the Provincial Councils and the Second Chamber, did not confer a federal character to the constitution and thus did not pose a threat to its unitary character. He said the slight advance from the District Council system was necessary to persuade the TULF to give up its demand for a separate state of Tamil Eelam.

Buddhist priests were not prepared to concede even that slight improvement to the Tamils. The influential and conservative Buddhist priest Madihe Pannaseeha thera convened a meeting at Naga Vihara at Sri Jayawardhenapura, Kotte and told the Buddhist priests that the proposed arrangement posed a threat to the constitution, Buddhism, the Sinhala race and the country. He appealed to them to start a satiyagraha campaign to oppose the Provincial Scheme. An anti- Jayewardene clique in the UNP also geared itself to oppose the proposed legislation.

Madihe Pannaseeha thera

The TULF politbureau met in Colombo to consider the draft proposal. Sivasithamparam and the extremist group in the party said the proposals failed to meet the aspirations of the Tamil people and wanted it rejected. Amirthalingam and the moderates said, though the proposals were not satisfactory, they should not be rejected. That would close the door for further negotiations, they argued. They should press Jayewardene to improve the proposals, they argued.

The hopes of the TULF moderate group were dashed when the conference met on 21 December. Jayewardene called on the delegations to submit to him in writing their views about his 14 December proposals. He requested the Maha Sangha to examine the proposals carefully. He said the government was prepared to go before the people by way of a referendum or an election and expressed the hope that the work done so far would bring peace, stability and unity to the country. He adjourned the conference without fixing a date to meet again.

Amirthalingam objected to the postponement. He said he wanted to make a statement. He was not allowed to. Jayewardene collected his papers and walked out. The TULF delegation was upset. The politbureau of the party met that night. The extremist group castigated Amirthalingam for placing faith in Jayewardene. They told the meeting the information that the army was being geared up for a massive crackdown on the Tamils in Colombo.

Amirthalingam issued a 2-page statement on 22 December. The concluding paragraph read: A careful study of the provisions of the draft bills placed before the conference will convince anyone that they fall far short of the regional autonomy indicated above (in Annexure C.) When we accepted the scheme of District Development Councils in 1980, it was clearly understood that it was not meant to be an alternative to our demand for a separate state.”

SLFP leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike in a five-page statement urged the people to reject the bills. She said, “The people of this country will be well advised to reject the draft legislation clearly and categorically.”

Industries Minister Cyril Mathew released a letter addressed to “Reverend Sirs, Honorable Ministers, Honorable Members of Parliament and Dear Friends.” In that letter, he said that he was “unable to advise anybody to agree to the proposed legislation.” He appealed to the government to drop it entirely.

Jayewardene sacked Cyril Mathew from his cabinet, charging that he had violated cabinet responsibility. There was no criticism. There was no revolt. Cyril Mathew simply melted into oblivion. His dismissal and fall proved beyond doubt that Jayewardene was the sole force during his time. All the others – Cyril Mathew, Gamini Dissanayake and Athulathmudali were his creations. He created them to give the impression to the country and the world that he was a prisoner of his ministers. It was not so. He was not even a “prisoner of circumstances,” the phrase he often used. He created the circumstances to suit himself.

Jayawardene told the cabinet on 26 December that he had decided to drop his proposals and to discontinue the All Party Conference. Athulathmudali, the conference spokesman, was told to announce that as the cabinet decision. He met the media in the evening and announced the decision. He also issued the following government communiqué:

“Some of the proposals which represented the views of the majority of the delegations of the All Party Conference were placed before the cabinet of ministers on Wednesday December 19, 1984 for discussions. They were discussed again on December 26. In the meantime, the Tamil United Liberation Front, which until December 21 was discussing the details of the system of government and decentralization of authority outlined in the proposals with the government delegation, had publicly proclaimed that no useful purpose could be served by discussing them further. The cabinet has therefore decided that no useful purpose could be achieved in discussing or arriving at a decision on these proposals. The cabinet requested His Excellency the President to continue his efforts to find a political solution while taking all measures to eradicate terrorism.”

Thus ended an yearlong exercise of ‘buying time” to strengthen the military apparatus. With the disappearance of Indira Gandhi from the scene, with India’s pressure eased, Jayewardene had prepared himself to take “all measures to eradicate terrorism.” And his scheme for a military solution was put into operation that very night. Four thousand Tamil youth were taken into custody in Colombo. Four days later, on 30 December, National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali announced stringent security measures in the north, including the “No Go” prohibited zone.

Amirthalingam returned to Chennai a dejected man. Yet he stuck to the theme of non-violent struggle which had lost relevance among the Tamil people. He told a public meeting in Karur in Tamil Nadu that the TULF would start a satyagraha soon.

The former editor of the TULF official paper Suthanthiran ridiculed Amirthalingam’s announcement. He said in his monthly publication, Vira Vengai,

“Tamil people are fed up with Amirthalingam’s antics. He had talked all these months with the Jayewardene government accepting the unitary constitution. Now, after the failure of the All Party Conference he is talking about satyagraha.

“We have seen this satyagraha umpteen times. They will sit in front of a temple, Mangayarkarasi Amirthalingam will sing songs. In the evening, they will drink fruit juice and disperse. It will cause no impact on the Jayewardene government.

Tamil militant groups had shown since August the manner of having impact on Jayewardene government. Jayewardene had made non-violence irrelevant.”

Jayewardene’s ambition when he assumed office in 1977 was to make history. He instructed the Daily News that all his speeches should be reported in full, the way he delivered them. They were historical documents, he said. His contribution to Sri Lankan history was to make non-violence useless to win a community its rights!

Next: Chapter 20. Violence Brought to the Fore

To be published October 15