by T. Sabaratnam, May 7, 2004

Chapter 1

Original index to series

Must Put an End

Shell-shocked Balthazzaar and his top men held a conference at Gurungar Camp on their return. The radio room had by this time informed Colombo about the blast and the death of 13 soldiers. Balthazaar got a call from Palaly and then Colombo headquarters. It connected Balthazar to army commander Lieutenant General Tissa Weeratunga who had been woken up by the headquarters.

“I’ve to inform the President. It’s too serious,” Weeratunga blurted. His voice showed that he was badly shaken.

Weeratunga woke up President Jayewardene. Weeratunga later told his officers that Jayewardene was angry when he broke the news. “We must put an end to this,” Jayewardene exclaimed. He asked Weeratunga to meet him in the morning.

The conference at Gurunagar considered three matters. Handling of the situation, handling of the dead bodies and strengthening the security of Jaffna City.

Lt. Gen. Tissa Weerathunge

Handling of the situation involved investigations about the blast. Munasinghe and the intelligence unit were detailed for that task. The bodies of the dead soldiers were in the Jaffna Teaching Hospital mortuary. An undertaker, A. F. Raymond of Colombo, was told to take the bodies to Colombo and prepare them there to be handed over to the families of the dead men. Additional army units were deployed to guard Jaffna city.

In the morning, Jayewardene presided over a top level security conference, in his private residence, Braemar, in Ward Place, Colombo. “What happened?” was the first question he asked. It was directed at Weeratunga. He had no reply. He was the military officer who declared at the end of 1979 that Tamil terrorism had been eliminated. He celebrated that event with a special party which Jayewardene attended.

One of the officers who attended the Ward Place conference told me that Jayewardene was angry. “This should end. We cannot allow this to go on,” he kept repeating. The officer said he sounded ominous when he said this.

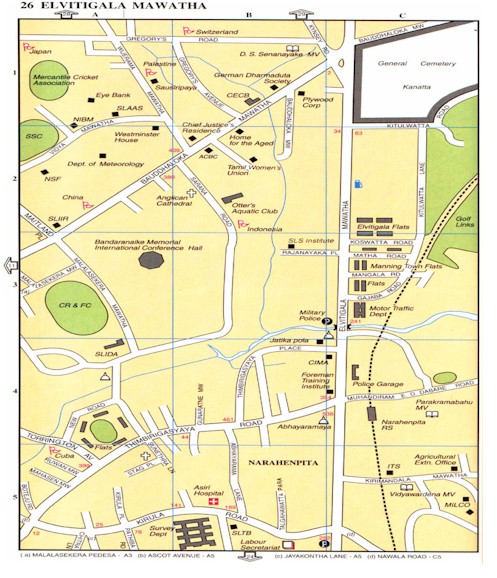

The conference decided two things. The first was to send Weeratunga to Jaffna. The second was to give the soldiers a full military funeral at Kanatte, the main graveyard in Colombo.

The decision to accord a military funeral at Kanatte was taken by Jayewardene. Weeratunga preferred the normal practice of handing over the bodies to the families for a family funeral with military honour accorded. Police officers who participated in the absence of Inspector General Rudra Rajasingham, who was on circuit at Nuwara Eliya, also supported handing over the bodies to the families. The police officers expressed their fear that a funeral at Kanatte would create a dangerous situation. Defence Ministry authorities also supported that view. Jayewardene over ruled those objections. He said that this was an unusual situation where 13 soldiers had been killed and they should be honoured in a suitable manner.

Radio Messages

Weeratunga flew to Palaly in the afternoon of 24 July in an air force plane and from there to Gurunagar Camp in an army helicopter. While he was on his way, things were taking an ugly turn in Jaffna. Upsetting radio messages started pouring in from Palaly Army Base in the afternoon (24 July 1983).

Munasinghe quotes two of them in his book A Soldier’s Version. One of them said, “Soldiers from Mathagal and VVT (Valvettithurai) are going on the rampage. They are killing innocent people.”

The next message he quotes reads, “A truckload of soldiers just left Palaly Base towards Jaffna town, smashing through the main barrier on their way out.”

The next message he quotes reads, “A truckload of soldiers just left Palaly Base towards Jaffna town, smashing through the main barrier on their way out.”

The rampage had started when Weeratunga landed at Gurunagar in the afternoon of 24 July 1983. Despite that, all the senior members of the army unit in Jaffna were assembled at the helicopter pad of the Gurunagar Camp to receive their commander.

Weeratunga presided over a conference at which Balthazzar briefed him about the LTTE ambush of July 23 night. Balthazzar also told him of the causalties and the action he had taken to dispatch the bodies to Colombo. Weeratunga was also briefed about the messages received from Palaly.

Weeratunga told the officers that his main concern was the dispatch of the bodies to Colombo. Balthazzar told him that ten bodies were in good condition and three were slightly damaged. He said Second Lieutenant Vaas Gunewardene and the two soldiers in the back seat of the jeep had suffered the impact of the explosion. He said the bodies would be flown to Colombo and police had been instructed to inform the relatives to go to A. F. Raymond with clothes in which the bodies would be dressed up. Hospital sources told me that none of the bodies were badly damaged and they were identifiable. Munasinghe had, in fact, identified the body of Vaas Gunewardene, the worst affected, by turning the head up. A relative of Vass Gunawardene who received his body had said that he was out of shape. Weeratunga thanked Balthazzar for acting quickly and expressed satisfaction with the arrangements.

Weeratunga took off from Gurunagar around 5.00 p.m. He told the officers who had gathered at the helipad at Gurunagar that President Jayewardene had decided to accord the fallen soldiers full military honours. He wanted to bury them at Kanatte and build a memorial structure.

Weeratunga told the officers that he wanted to follow the bodies to Colombo. But he returned 30 minutes later. He told the surprised officers who had hurried to the helipad to receive him that he had received instructions from the Government through the telecommunication system of the helicopter to stay over in Jaffna for the night.

Palaly air control tower later said that army headquarters contacted it and frantically wanted connection established with Weeratunga. “We connected the call to the helicopter,” an officer who gave the connection said.

Why was Weeratunga sent back? I tried to get the answer from my contacts. The only answer I got was that President Jayewardene wanted Weeratunga to stay back and keep the soldiers under control. I find it difficult to accept that explanation. I find it difficult to accept it because eye-witness accounts and records about Weeratunga’s activities after his return to Gurunagar does not support that explanation.

What did Weeratunga do after his return to Gurunagar?

Munasinghe records Weeratunga’s activities after his return in his book, A Soldier’s Version:

“We were all tired after a sleepless night. Still, all of us, the seniors, were at the temporary Officers’ Mess by evening on 24 July 1983. Gen. Weeratunga also joined us for a drink. We discussed what should follow. Instructions were disseminated from the Security Force Headquarters to all troops to be vigilant and all officers were specifically instructed to ensure strict discipline among the troops.

Army Commander’s Anger

“Gen. Weeratunga received many telephone calls from Colombo. One caller was the Secretary Ministry of Defence. Another was His Excellency, the President. We heard the General discussing the funeral arrangements of the slain soldiers. The General passed down instructions in detail to his senior staff at Army Headquarters in Colombo. A short while later, I noticed the General was very angry and retorted to one of the callers, “I will not bury even my dog in Jaffna or Vavuniya.” His adamant position was that all dead bodies must be handed over to the families for last rites.

“The General explained to us that the higher authorities wanted the dead men to be buried in Jaffna or to cremate them in Vavuniya.”

The request to bury or cremate the bodies in Jaffna or Vavuniya was made by General Sepala Attygalle who had returned from Kanatte where the crowd had started shouting against the government. Attygalle went to the cemetery a little after 6 p.m. with Deputy Defence Minister Weerapitiya to asses the situation after police intelligence informed the president about the situation that was developing at Kanette.

I was in my home at Dehiwala when my Associate Editor (News), N. R. J. Aaron, telephoned around 4 p.m. and asked me to report for work immediately. He told me that the funeral is going to be held at Kanatte. I was aware by that time about the Thirunelveli blast. I was on night duty that day and, it being a Sunday, I normally reported for duty at 6 p.m. I was then Deputy Editor (News) of Daily News, Sri Lanka’s popular English language daily.

Aaron told me, “The decision to hold the funeral at Kanatte is still a secret. They have fixed the funeral for 5 p.m. We have been asked to send reporters and photographers. I am sending Piya and two reporters.” Piya was W. Piyadasa, our top photojournalist.

I later learnt that the Information Department had made similar requests to Rupavahini and the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation.

I reached Lake House by 5 p.m. and found things normal. The provincial edition was almost ready and the lead story was about the LTTE attack. Piyadasa and two reporters had left for Kanatte by about 4.30 p.m. with their colleagues from Dinamina and Thinakaran, our Sinhala and Tamil sister papers.

Our reporter phoned from A. F. Raymond (there were no mobile phones then) around 5 p.m. to say that the funeral was getting late. “The bodies have not left Palaly. The relatives of the dead have come. A crowd is collecting,” he reported.

He added that arrangements for the funeral were complete. A few soldiers and policemen were on guard duty inside and outside the cemetery. Graves had been dug. The army band had arrived. Buddhist priests had been brought to perform last rites. Television crews was getting ready. Arc lights had been fixed around the burial site. “No senior police or army officers have come,” he said.

Then he said, “Piya is here. We were told some ministers are coming to the parlour to pay their last respects.”

What delayed the dispatch of the bodies from Jaffna is still unexplained. Weeratunga left Gurunagar around 5 p.m. by helicopter to Palaly to follow the plane carrying the bodies in the airforce plane. He left Gurunagar after Balthazzar told him that the bodies were about to be transported from Jaffna Hospital to Palaly. The Jaffna Hospital authorities told me that the bodies were removed from the mortuary before 5 p.m. They told me that the delay was at Palaly. They said there was a lot of confusion at Palaly due to conflicting orders from Colombo. A top military officer who was at that time at Palaly told me that the confusion was the result of Jayewardene’s orders. He had asked Weeratunga to stay in Gurunagar. That disrupted all other arrangements. Dinamina’s Mount Lavinia correspondent, who was posted at Ratmalana to cover the arrival of the bodies, told me later, “There was utter confusion at the Ratmalana airport.” He told me in pithy Sinhalese, “No one knew who was coming and who was going.”

Kanatte General Cemetery, Colombo (upper right)

Similar confusion prevailed at A. F. Raymond where some of the relatives of the slain soldiers were gathered. At Kanatte, where all sorts of elements were gathering, there was utter disorder. At Braemar, where ministers and top officials were offering contradictory advice, the situation was worse than at Angoda.

As dusk descended, confusion was getting confounded. Our reporters noticed a variety of agent provocateurs entering the cemetery. They noticed a group of short-cropped young men wearing white T-shirts and shorts pushing their way to the graves. The reporters first thought that they were army deserters from Rajarata Rifles who had revolted in June. Later they found that they were not deserters but soldiers from the Army Camp at Narahanpita Road near Kanatta.

Anger against Jayewardene

The soldiers were the first group of men to give direction to the angry and emotional crowd. They went up to the graves and pushed the soil into the pits shouting, ‘Give the bodies to their relations,’ and ‘Don’t bury them here like dogs.’ The message struck the veins of the wailing relatives. They joined. The crowd chorused, “Give the bodies to the relatives.” Assistant Police Superintendent Gafoor who was there to oversee the arrangements went up to see what the trouble was. Someone removed a plank and pushed Gafoor with it. He lost his balance, but managed to escape from falling into one of the pits.

Police Superintendent Abdul Gafoor chasing crowds at the General Cemetery, Borella, July 24, 1983

The crowd went berserk. It smashed up the brassware brought by A. F. Raymond for the funeral ceremony. The crowd trampled the graves. The mob uprooted tombstones. The Buddhist priests and relatives of the dead fled in fear.

The time was closing on 7 p.m. Deputy Defence Minister Weerapitiya and Defence Additional Secretary Sepala Attygalle came to the cemetery. They went up to Rudra Rajasingham, who had rushed to Kanatte, cutting short his circuit at Nuwara Elya. They asked him about the situation. Rajasingham told them an ugly situation was developing. Attygalle told Rajasingham to ‘hold the fort’ and went to Ward Place to report the situation to Jayewardene.

Around 7.30 pm Piyadasa and a reporter returned to Lake House to catch the second edition which goes to bed at 9 p.m. Piyadasa brought pictures of the disturbance, but Lake House chairman Ranapala Bodinagoda who was shunting between Ward Place and the Daily News editorial told editor Manik de Silva to tone down the report. “Dangerous situation is developing,” he panted.

Piyadasa, who showed the photographs to Bodinagoda, said, “Things are getting out of control.” He was agitated. He came to me and said, “Saba! Be careful. The public anger just now is against the government. Attempts have begun to turn the anger against the Tamils.” Piyadasa was close to the UNP hierarchy.

Piyadasa also told me that the bodies of the soldiers had been ‘reduced to powder’ (kudu karala was the phrase he used). That was what army officers told the reporters and the relatives of the dead soldiers who were pestering the officers to hand over the bodies to them. The officers also told them that the government had decided to have a collective funeral at Kanatte because the bodies had been blown to pieces and were unidentifiable.

The second reporter and his colleagues returned to Lake House around 8. 30. They said the funeral at Kanatte had been cancelled and the crowd had turned boisterous when the cancellation was announced over the loudspeaker. “The people are shouting against the President and the government,” they said.

Our inquiries revealed that a small group of Colombo University students entered the scene around 8.30 p.m. They were a dissident group of the Communist Party. Two of them addressed the crowd and said President Jayewardene and the government should take the blame for the death of the soldiers. They tried to lead the crowd to Ward Place.

Their attempt was thwarted by the police. Sensing the growing anti-government sentiment, Deputy Inspector General of Police Edward Gunawardene, who was present at Kanatte, acted fast. He ordered the police to seal off Ward Place by erecting barriers at the top of Kynsey Road and at the top of Ward Place.

As the angry throng stormed out of Kanatte, the university students realized that the situation had got out of control. They bolted. They returned to their respective homes.

Around 10 p.m. we in the Daily News editorial saw smoke rising from the direction of Borella. I contacted the Fire Brigade. The officer on duty said the mob was setting fire to Tamil-owned shops at Borella junction. Then we saw flames leaping up. At that time the new wing of Lake House was not constructed. Fort Railway station, Pettah and beyond were visible from the Daily News Editorial. Colombo had begun to burn.

Killing Spree

Jaffna was burning by that time. Truckloads of soldiers who left the Palaly Camp drove to the site of the ambush. They smashed the shops all the way from Palaly to Thirunelveli. At Thirunelveli they parked the trucks near the junction and launched a ferocious revenge attack on Tamil civilians. They commenced their attack by demolishing the cement-roofed shop from where Sellakili had exploded the land mines. They then knocked down the parapet walls which the Tigers had used for their ambush. They then burnt the houses on both sides of the road. They opened fire on the people they found on the road. They then went back to the camp and returned on Monday morning.

The soldiers saw a 10-year-old boy cycling from the direction of Kalviyankadu holding a loaf of bread in one of his hand. They ordered him to stop. As he alighted from the bicycle a soldier shot him in the head. He fell dead and his body, bread and the bicycle were on the road till noon an eyewitness said. “His brain matter was strewn on the road,” Munasinghe recoded in his book. He said he drew a deep breath when he saw the scene.

The soldiers spread into the interior on either side of the road, torching the houses and shooting people. In one of the houses, they found an old couple. They shot both and set fire to the house.

The soldiers from Mathagal Camp were no better. They went to Manipay, stopped a bus and ordered all occupants to get down. They asked the nine students clad in white school uniform to stand in a line. Then they opened fire. Six fell dead and the other three were seriously injured. Soldiers from the Valvettithurai Camp were equally cruel. They burnt shops and houses.

Fifty-one persons were killed and over 100 injured in these three places, the report compiled by the Jaffna Government Agent revealed. The report also said over 100 shops and houses were damaged or burnt.

Tamil students killed in Jaffna 1983

Weeratunga was at that time in the Gurunagar Camp on 24th night. He was constantly on the telephone. He was getting reports about the developments in Colombo. He went out to find out the situation in Jaffna only at 10 a.m. on Monday (July 25).

Munasinghe records the visit to Thirunelveli in his book thus:

“The time was around 10 a.m. on 25 July 1983. We started our vehicles and sped towards Thirunelveli. Gen. Weeratunga too joined us. Gun shots were heard by all of us. We formed into small groups and went in different directions and screaming at everyone to stop firing and to fall back on the road.

“I was walking with Lt. Rajive Weerasinghe who was a platoon commander of the 1st Battalion of the Sri Lanka Light Infantry. Dead bodies were strewn here and there. I took a deep breath when I saw the dead body of a child of about 10 years of age. A loaf of bread and the bicycle he was riding were by his side. His brain matter was on the road. Someone had shot him dead at point blank range.

“Just then I saw a soldier taking cover behind a tree about 100 meters away. I had only a pistol. Lt. Weerasinghe had his personal weapon. For a moment, I thought that the soldier was trying to shoot both of us. Fortunately, Weerasinghe identified the soldier. The soldier quickly responded to Weerasinghe’s call by coming onto the road. It took us about an hour to discipline the rampaging soldiers at Thirunelveli junction. Gen. Weeratunga was very angry. The rampaging men were arrested. The few non-commissioned officers were stripped of their ranks. By afternoon the same day they were all dispatched under escort to Anuradhapura remand prison.

“Similar killings had taken place at VVT (Valvettithurai) and in areas surrounding the Mathagal Camp. Later, we heard that the Major in charge of the Mathagal Camp had pleaded with his men to remain in the camp. The men insisted. The major, when everything failed, lay down on the road blocking the vehicles carrying the angry men. The men lifted him away and the vehicles proceeded. Killings continued.”

Many questions arise about the conduct of the army commander. He was briefed about the radio messages of soldiers killing innocent civilians. He waited till 10 a.m. to go out and restore discipline. Why?

And according to President Jayewardene he was not informed about the Jaffna carnage for almost a fortnight.

David Beresford of the Manchester Guardian (Guardian Weekly 14 August 1963) questioned President Jayewardene on 7 August about the Jaffna massacre, especially about the failure to hold inquests for the civilians killed by the rampaging troops. Jayewardene’s reply was, “I didn’t know until a couple of days ago. It is too late now.”

Jaffna home 2001

Beresford told Jayewardene that the army had killed 51 civilians including children and an old couple in cold blood. Jayewardene said the number of deaths was not that large. It was about 20, he said.

To justify his position that he came to know about the Jaffna butchery only ‘a couple of days ago’ Jayewardene told Beresford that the army had withheld from him the information about the Jaffna massacre.

Why did Weeratunga hide that information from Jayewardene?

Were the Jaffna incidents, along with the subsequent pogrom in the South, part of the ‘Final Solution’ for the Tamils?

These questions and suspicions still linger in the minds of the Tamil people.

This was the suspicion that motivated Pirapaharan.

In March 1984, barely a year after the July holocaust, Pirapaharan told Anita Prathap, “Our view is that the July holocaust was a pre-planned, well-orchestrated genocidal pogrom against the Tamils, carried out by the racial elements of the ruling party.”

For the record, I am quoting the question and answer, because it is this view that shaped Pirapaharan.

Q: The Liberation Tiger for Tamil Eelam (LTTE) staged the 23 July 1983 ambush in which 13 Sinhalese soldiers were killed. The ambush was allegedly the reason for the Sinhalese retaliation on innocent Tamils. Did you expect such a massive retaliation?

A: The July violence should not be assessed simply as a Sinhala retaliation for the guerrilla ambush. This view is a gross oversimplification of the event. The island has been plagued with anti-Tamil racial violence which erupts periodically over the years. There were violent racial holocausts even before the emergence of our movement. Violent riots erupted in Trincomalee a couple of weeks before the ambush. Therefore, the phenomenon of anti-Tamil racial violence cannot be traced to a single event. We are engaged in a protracted guerrilla warfare. There has been several guerrilla raids, several ambushes, and we have killed several Sinhala soldiers and policemen. The July ambush was only a part of the warfare we are engaged in. It is incorrect to assume that one particular military operation has precipitated the entire violence. The July riots, you would have certainly observed, was not only aimed at the physical extermination of our people, but it was also aimed the destruction of the economic power base of the Tamils in Colombo. Our view is that the July holocaust was a pre-planned, well-orchestrated genocidal pogrom against the Tamils, carried out by the racial elements of the ruling party. Initially, these racist elements did attempt to put the whole blame on the Tiger. Then, suddenly, they blamed the left parties for the riots. But in fact, it is the racist leaders of the present government who should take responsibility for this tragic loss of life.