by T. Sabaratnam, March 18, 2005

Chapter 38

Original index to series

Original Chapter 39 [renumbered from Chapter 37]

On 16 August 1985, the day on which Hector Jayewardene disappointed the Tamil delegation and India with his ‘new proposals’ at Thimpu, Tamil militants exploded a land mine to blow up an air force jeep speeding along the A9, the Vavuniya – Jaffna highway. The militants missed their target and no one was injured, but the air force personnel retaliated. They shot dead 15 civilians and torched several shops and houses along the road north of Vavuniya.

In the night, about 400 soldiers who were transported in around 50 army vehicles to the farming villages Irampaikulam, Thonikkkal, Koolaipillaiyar Kulam, Koodamankulam and Moonrumurippu [north of Vavuniya] cordoned off the area. The residents who came out of their huts on hearing the barking of dogs were ordered to raise their hands and led to a lonely spot. The soldiers searched the thatched mud-floored huts and shot dead some of the youths in the presence of their family members. They marched the others to the spot where they had assembled several others.

“A senior officer barked, ‘All the devils below 40 years come and stand here in a line. Others sit on the ground.’ I am 52 years old. I sat on the ground. My sons went to the road side and stood in the line,” Kanthavanam Kumaran told Amnesty International in an affidavit he submitted to it. “There were over 50 youths. They were all shot dead,” he added.

In another affidavit Santhini, wife of a 29-year Sivakumaran, described the horror she underwent that night. “When the soldiers came to my house I hid my husband in a corner. The soldiers found him, ordered him to raise his hands and fired on his forehead. His head shattered. Brain matter was strewn all around. He died in my presence chanting my name,” she said.

The massacre continued for two days. Over 120 persons were killed; eight of them children below ten years of age. The organizer of the Sarvodaya movement and his wife were among those killed. Forty bodies were handed over by the army to the Vavuniya hospital. The rest were abandoned at the scene of the shooting.

Uprooting Tamils

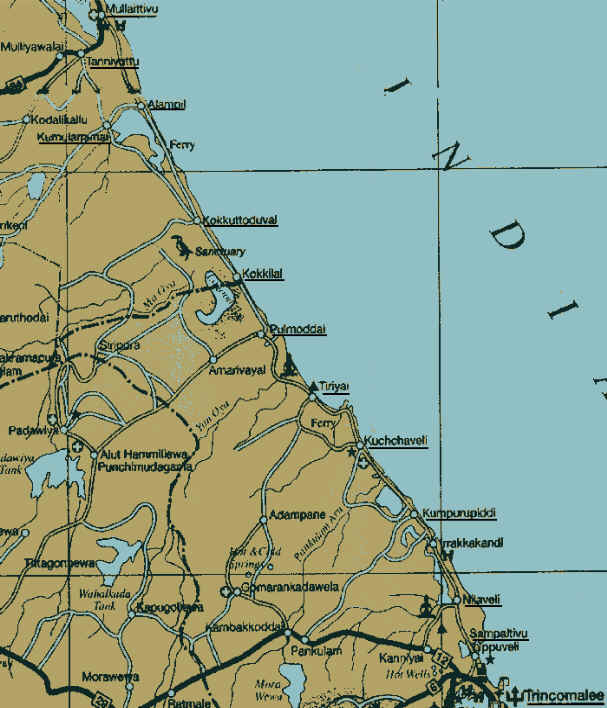

On the same two days, the army massacred over 100 innocent Tamil civilians in the Trincomalee district. Armed soldiers cordoned off the traditional Tamil villages Pankulam, Iranaikeni and Sambaltivu, shot and killed innocent villagers. Eyewitness accounts of the army killings have been filed with Amnesty International and other human rights organizations. At Sambaltivu, the arrested youths were lined up and shot. At Pankulam, Sinhala Home Guards joined the soldiers in this dance of death.

These massacres were part of the Jayewardene government’s plan to create a military buffer zone – Lalith Athulathmudali called it the ‘no-go zone’ – between the Northern Province and the rest of Sri Lanka. The scheme, as I have already pointed out, was based on Israeli advice. “We will contain terrorism to the north,” Athulathmudali kept repeating during this period.

The creation of the buffer zone and the strict implementation of the prohibited zone along the seacoast between Mullaitivu and Trincomalee were intended to severe the northern province from the eastern province. The buffer zone will prevent the flow of men and material along the land routes. Strict implementation of the prohibited zone was intended to curtail movement by the sea.

Lalith Athulathmudali planned massive settlements of landless Sinhala peasants – he said he would settle 200,000 cultivators – in the buffer zone, a wide corridor stretching from the western Mannar coast to the eastern coast of Mullaitivu. He also planned the settlement of Sinhala fishermen along the Mullaitivu – Trincomalee coast. These areas were dotted with traditional Tamil agricultural and fishing villages. Grabbing these rich agricultural lands and fishing grounds for the Sinhalese was Jayewardene government’s goal.

Lalith Athulathmudali planned massive settlements of landless Sinhala peasants – he said he would settle 200,000 cultivators – in the buffer zone, a wide corridor stretching from the western Mannar coast to the eastern coast of Mullaitivu. He also planned the settlement of Sinhala fishermen along the Mullaitivu – Trincomalee coast. These areas were dotted with traditional Tamil agricultural and fishing villages. Grabbing these rich agricultural lands and fishing grounds for the Sinhalese was Jayewardene government’s goal.

The operation to uproot and chase the Tamils from these villages was planned and directed by Athulathmudali. The operation was commenced in the beginning of 1984. Lalith Athulathmudali intensified the operation in December 1984 and January 1985 following the LTTE attack on Kent and Dollar farms. The following traditional Tamil villages were uprooted during those months: Kokkilai, Karunartukerni, Kokkudoduwai, Nayaru, Kent and Dollar farms, Andankulam, Kanukkerni, Untharayankulam, Udanga, Othiyamalai, Periyakulam, Tanduvan, Kumulamunai (East and West), Tanniyoottu, Mulliyavalai, Chemmalai, Thannimurippu and Alampil. (Refer Chapter 25 of this volume).

Destruction of Tiriyai

In June 1985, the second stage of the plan to hound the Tamils from their traditional villages was launched. Tiriyai was an agricultural village north of Trincomalee. It was the land link between the Mullaitivu and Trincomalee districts. Chasing the people out of that Hindu village would break the territorial link between the northern and the eastern provinces. The fate that fell on Tiriyai was recorded by Simon Winchester in The Sunday Times Magazine of 18 August 1985. The extract:

“The village of Tiriyai, a few miles north of the famous old Royal Navy base at Trincomalee, is in normal times a contented and pretty little place, best known for its market where local farmers come to trade cashew nuts and cattle. Eastern Sri Lanka is dry and sultry, and the farms there are not especially prosperous, so none of the 2,000 villagers of Tiriyai has much money. But nobody starves. Everyone gets along. The village, in spite of its poverty, has an undeniable dignity, and serenity about it.

Once in a while, tourists arrive, although the drive is long and bumpy and there are enough stray elephants around to make a lone driver rather nervous. But no tourists visit Tiriyai today, and nor will they for many years to come.

And since the terrible morning of June 15 last, hardly anyone lives in Tiriyai, either. The village has been almost totally wrecked. Nearly every house, shop, farm has been burned. Cattle have been butchered in the fields. Such carts and motorcycles the villagers once owned lie rusting on the sandy roadsides, smashed to pieces, useless. Just a few people – old women, bedridden men and young children – remain, some still whimpering with the memory of what happened on that fateful Wednesday morning.

Just before eight, when the farmers were already out in their fields and the women were attending to their domestic routines, two army helicopters appeared in the sky. They flew low over the village, and, without any warning, opened fire with machine guns. Villagers ran, in wild panic, into the low scrub that passes for jungle in these parts. But as they did so, a convoy of army trucks and buses appeared on the road from Kuchchaveli town that in normal times is a seaside resort well known to German and Dutch holidaymakers, but during the past year has been deserted, except for a monstrous new army base.

Infantryman, fully equipped for battle, spilled from the vehicles. Some were carrying jerrycans, others held flaming torches. Systematically, they went from house to house, pouring paraffin on to the grass roofs, lighting them, moving on. They set animals free, and shot them down. They stormed into the tiny library, pulled out all the books – no more than a couple of hundred at the most – and made a bonfire of them. They wrecked the half dozen International Harvester tractors, and set fire to their wooden trailers.

And all the while, the villagers looked on from the security of the jungle, watching with stunned amazement as their community was destroyed. Many of them started running, and ran and ran, deep into the forests, and have not been accounted for since. Fewer than a hundred waited until the marauders had gone at dusk and then crept back to see what they could salvage. There was not much. A few sacks of paddy had escaped the inferno. A dozen houses were habitable, though burned. But the school had gone and the post office. There was no food left in the two shops, which had in any case been utterly wrecked. And, most terrible of all, the Hindu temple had been sacked, and the images of Vishnu and Shiva had been mutilated and broken….

Coast of Sri Lanka north of Trincomalee

Most of the people walked through the forest to Mulliyavalai and then to Jaffna. From there some families went as refugees to Tamil Nadu. But some returned to their village. And by 1990 when the Second Eelam War broke out, records show, there were 1475 families in Tiriyai. The village was completely erased in 1990.

In June 2002, about three months after the ceasefire came into effect, representatives of over 25 families who had fled from Tiriyai, led by Trincomalee Member of Parliament R. Smpanthan, visited the destroyed village. They went up to the Navy Camp, housed in the Tiriyai Tamil Maha Vidayalaya [high school] building which stands at the entrance of the village. They were told that they would not be allowed to proceed further. When Sampanthan insisted visiting the village, saying the former occupants want to return, he and three others were taken to a mound behind the Navy Camp and told to look in the direction of the village. The rest of the delegation was asked to wait near the historic Varatha Vinayagar temple, a portion of which had been spared. Those on the mound looked. They were down hearted.

On their return, Sampanthan told the others who had waited behind: There is no village. There are no houses. There was no trace of the Muthumari Amman temple. Of the Pillaiyar Kovil, the statue is still standing. A picture of Buddha is pasted on it. All that is standing in this vast village is the building of the Tamil Maha Vidyalaya [high school] and the two houses in front of it. They are standing because the Navy is occupying them.

Sampanthan added: The village had been systematically destroyed to prevent the return of the people. It was a well-planned destruction of a historic village where over 2000 families lived. By 2004, some of the former inhabitants had returned to the Tiriyai vicinity.

Uprooting of the Tamil villages was suspended once the ceasefire came into operation on 18 June 1985 prior to the Thimpu talks. But it was resumed on the night of 16 August, the very day Hector Jayewardene presented the government’s new proposals at Thimpu. By that time, the Tamil delegation had indicated that it would reject the ‘new proposals.’ Amirthalingam called the new proposals ‘old wine in a new bottle.’ He said the government had rehashed the proposals his party had rejected in December 1984.

Violence was unleashed to beat the Tamils into submission; into forcing them to accept what was offered at Thimpu. This strategy was nothing new. That was what Jayewardene had been doing since he was elected to power in 1977. He did that not only to the Tamils, but also to his own people, the Sinhalese, and anyone who dared to oppose him.

Tamils Reject Proposals

At Chennai, ENLF leaders decided to reject the new proposals given by the government. Balasingham was instructed to tell the Tamil delegation to make a joint statement rejecting the proposal. While Satyendra, TULF leaders and the militants were busy drafting the joint statement in their hotel at Thimpu, Romesh Bhandari was briefed about the impending collapse of the talks. He flew to Thimpu and met with the Tamil delegation on 17 August morning. The meeting was a disaster. He asked the Tamil delegation to come up with their own proposal. Tamils argued that they had set the parameters for a solution and it was the government’s responsibility to come up with an acceptable alternative to their demand for a separate state. An annoyed Bhandari blamed the Tamils of being ‘intransigent’ and of adopting an ‘inflexible attitude.’ “What the bloody hell can you do with these abstract principles?” he blurted.

Satiyendra was offended. He objected to the phrase, “What the bloody hell.” He said it was unparliamentary. He accused Bhandari of being unconcerned about the interests of the Tamils. He told Bhandari he exhibited the master-servant attitude (Indians=masters, Tamils=servants). Though Bhandari said he did not mean to insult the Tamils, the sour taste the incident created persisted.

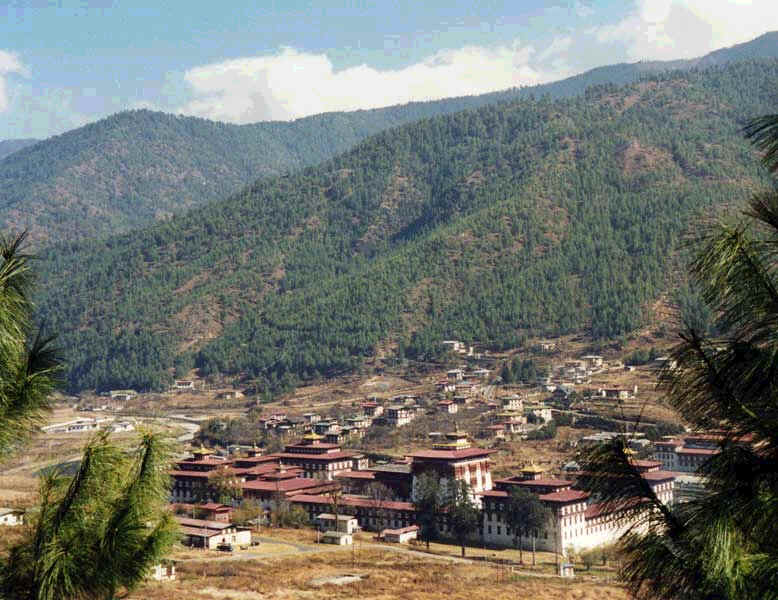

Thimpu

Bhandari also met the government delegation separately. Bhandari told Hector Jayewardene that his proposal fell far short of the Tamil and Indian expectations and requested him to make improvements. Hector Jayewardene promised to make improvements during the discussions. But in Chennai, the ENLF issued a statement dubbing the Sri Lankan proposals “one step backward.”

While things reached a crisis stage in Thimpu, Pirapaharan received disturbing news from Vavuniya and Trincomalee. He was briefed about the army atrocities in those places. He instructed Balasingham to summon an emergency meeting of the ENLF leaders. Pirapaharan told Balasingam that he was on his way to participate in the meeting.

That day, 17 August, was a crucial day in the history of Sinhala- Tamil relations. The morning negotiation session in Thimpu commenced at 10 a.m. as usual. And around that time in Chennai, ENLF leaders met to take a historical decision. In Thimpu, the Tamil delegation read their joint statement rejecting the government proposals. In Chennai Pirapaharan told the other three leaders – Sri Sabaratnam, Pathmanabha and Balakumar – that the only way to win the rights of the Tamil people was war. He said the Sinhalese were out to destroy the Tamils and the only role the militants had was to protect the Tamils.

On that day, Pirapaharan had made a firm decision: the rights of the Tamil people can only be won through armed struggle.

In Thimpu, the Tamil delegation read the following joint statement rejecting the government proposals:

We, the Tamil delegation, being solely representative of the Tamil people at the Thimpu talks, have given careful consideration to the proposals made, on the 16th of August 1985, by the Sri Lankan Government delegation. We state that we are constrained to reject the proposals as they fail to satisfy the legitimate political aspirations of the Tamil people.

The Thimpu talks were convened at the initiative of the Government of India. It was an initiative which we welcomed, particularly in the context of Prime Minister Shri Rajiv Gandhi’s statement concerning the need to find a just and lasting solution to the Tamil national question.

At the commencement of these talks in early July 1985, the Sri Lankan Government presented certain proposals, which were in substance, a repetition of the proposals by the Government to the aborted All Party Conference in Colombo in December 1984. These proposals had been rejected by the TULF and the action of the Sri Lankan government in placing similar proposals once again at the Thimpu talks called in question the good faith of the Government and its commitment to seek a just solution at these talks.

The intent of the proposals that were presented was clear. Although it was stated that power would devolve on District Councils, in fact, the District Councils were without executive power. Again, even their limited legislative power to enact subsidiary legislation was made subject to the control and approval of the President. Finally, the funds to be placed at the disposal of a District Council were to be determined at the discretion of a commission appointed by the President. The proposals submitted by the Sri Lanka Government did not devolve power from the centre: they reinforced the power of the centre to manage the districts. The proposals constituted evidence of the intention of Sri Lankan government to manage and control the Tamil people even in the relatively insignificant functional areas where the District Councils were given some jurisdiction.

We, the Tamil delegation, consisting of six organisations, unanimously rejected these proposals because it was our considered view that any meaningful solution to the Tamil national question must be based on the four cardinal principles enunciated by us.

The talks were thereafter adjourned to the 12th of August 1985, on which date the Sri Lankan Government made a statement setting out its understanding of the four basic principles enunciated by us and the Sri Lankan government denied that the Tamils constituted a nation, that the Tamils have an identifiable homeland, and further that the Tamil people have the right of self determination. The Sri Lankan Government further questioned our right to represent or negotiate on behalf of the plantation Tamils in the Island.

We responded by our statement of the 13th August 1985, and pointed out that our demand for self-determination had evolved and taken shape historically through the determined political struggles of our people. We stated that the Tamils of Eelam or Tamil Eelam, constituted a nation with a common heritage, a common culture, a common language and an identified homeland, and further that they were a subjugated people and as such they had the inherent right to free themselves from an alien subjugation. It is the right of self-determination that has come to be recognised as one of the peremptory norms of general international law. We stated that in upholding the right of self-determination, we as a people have the liberty to determine our political status, to freely associate or integrate with an independent state or secede and establish a sovereign independent state. We mentioned, however that the enumeration of the principles enunciated by us did not entail that we were opposed to any rational dialogue with the Government of Sri Lanka on the basis of such principles.

At the subsequent talks on the 13th and 14th of August 1985, the Sri Lankan Government delegation failed to engage in any discussion concerning the basic framework that we had enunciated. This was despite the circumstance that the members of the Tamil delegation specifically requested the Sri Lankan Government delegation to honour that which it had stated in its own statement of the 12th of August i.e. to engage in a ‘fruitful exchange’ of views.

The Sri Lankan government delegation presented instead its so-called ‘new proposals’ on the 16th of August 1985. These ‘new proposals’ are a rehash of the earlier proposals with the right to certain District Councils to function as Provincial Councils.

The ‘new proposals’ do not recognise that the Tamils of Sri Lanka constitute a nation. The ‘new proposals’ do not recognise that the Tamil-speaking people have the right to an identified homeland. The ‘new proposals’ do not recognise the inalienable right of self-determination of the Tamil people. And finally the ‘new proposals’ do not secure the fundamental rights of the Tamil people and any solution to the Tamil national question is inseparable from the resolution of the problems of the plantation Tamils in the Island. And accordingly, the ‘new proposals’ fail to satisfy the legitimate political aspirations of the Tamil people.

We may add that the so-called ‘new proposals’ are in fact nothing new. As early as 1928, the Donoughmore Commission recommended the establishment of Provincial Councils on the ground that it was desirable that a large part of the administrative work of the centre should come into the hands of persons resident in the districts and thus more directly in contact with the needs of the area. Twelve years later the Executive Committee of Local Administration, chaired by the late S.W.N.D. Bandaranaike, considered the proposal of the Donoughmore Commission and in 1940, the State Council (the legislature) approved the establishment of Provincial Councils. But nothing was in fact done, though in 1947, on the floor of the House of Representatives, the late S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike again declared his support for the establishment of Provincial Councils.

In 1955, the Choksy Commission recommended the establishment of Regional Councils to take over the functions that were exercised by the Kacheries and in May 1957, the government of the late S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike presented a draft of the proposed Bill for the establishment of Regional Councils. Subsequently, in July 1957, the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact made provision for direct election to Regional Councils and also provided that the subjects covered by Regional Councils shall include agriculture, cooperatives, lands and land development, colonisation and education. The Pact, however, did not survive the opposition of sections of the Sinhala community which included the United National Party.

In July 1963, the government of Mrs. Bandaranaike declared that ‘early consideration’ would be given to the question of the establishment of District Councils to replace the Kacheries and the government appointed a Committee on District Councils and the report of this Committee containing a draft of the proposed Bill to establish District Councils but again nothing was in fact done.

In 1965, the government of the late Dudley Senanayake declared that it would give ‘earnest consideration’ to the establishment of District Councils and in 1968 a draft Bill approved by the Dudley Senanayake Cabinet was presented as a White Paper and this Bill provided for the establishment of District Councils. This time round, the opposition to the Bill was spearheaded by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party which professed to follow the policies of the late S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike who himself had in 1940, 1947 and again in 1957, supported the establishment of Provincial/Regional Councils. In view of the opposition, the Dudley Senanayake government withdrew the Bill that it had presented.

More than 50 years have passed since 1928 and we have moved from Provincial Councils to Regional Councils and from Regional Councils to District Councils and now from District Councils back to District/Provincial Councils. We have had the ‘early consideration’ of Mrs. Srimavo Bandaranaike and the ‘earnest consideration’ of the late Dudley Senanayake. There has been no shortage of Committees and Commissions, of reports and recommendations but that which was lacking was the political will to recognise the existence of the Tamil nation. And simultaneous with this process of broken pacts and dishonoured agreements, the Tamil people were subjected to an ever widening and deepening national oppression aimed at undermining the integrity of the Tamil nation.

The four basic principles that we have set out at the Thimpu talks as the necessary framework for any rational dialogue with the Sri Lankan Government are not some mere theoretical constructs. They represent the hard existential reality of the struggle of the Tamil people for their fundamental and basic rights. It is a struggle which initially manifested itself in the demand for a federal constitution in the 1950s and later in the face of a continuing and increasing oppression and discrimination, found logical expression in the demand for the independent Tamil state of Eelam or Tamil Eelam. It is a struggle in which thousands of Tamils have died and many thousands more have lost their properties and their means of livelihood – they have died and they have suffered so that their brothers and sisters may live in equality and in freedom.

And so, we declare here at Thimpu, without rancour, and with patience, that we shall speak at Thimpu, or for that matter anywhere else, on behalf of the Tamil nation or not at all. And we call upon the Sri Lankan Government to state unequivocally, whether it is prepared to enter into a rational dialogue on the basis of the framework set out by the cardinal principles enunciated by us at these talks.

There is one further matter of some considerable importance to which we wish to refer and we propose to do that in a separate statement.

Separate Development

The last line of the joint statement gave the indication of the separate development taking place in Sri Lanka and Chennai. On 17 August morning, the army continued the attacks in Vavuniya and Trincomalee. At Trincomalee, hundreds of soldiers and Home Guards surrounded Tamil villages, pulled out young males, lined them up and shot them. The forces withdrew only on the morning of 18 August.

In Chennai, the ENLF leaders were in session. Pirapaharan was furious. So were the others. Pirapaharan told the meeting their assessment that Jayewardene would use the Thimpu talks as a smokescreen to cover his hideous genocidal programme had proved correct. He said they should expose Jayewardene to the entire world. They decided to walk out of the Thimpu talks on which the global attention was focused.

Lawrence Thilagar

Pirapaharan, as usual, was methodical even in this emergency situation. Balasingham was told to find out whether TULF and PLOTE would join the walk out. They agreed. He then got Balasingham to find out whether India would dismantle the training camps in Tamil Nadu. RAW assured that that would not happen. Then Balasingham was told to make use of the hotline to inform the Tamil delegation to walk out. And on Pirapaharan’s instruction, Balasingham told Thilagar to get the PLOTE to lead the walk out.

At Thimpu Hector Jayewardene was telling the Tamil delegation that the Sri Lankan proposals could serve as the basis for discussion and asked it to look at the devolution package.

When the talks resumed at 4 p.m. the atmosphere was charged. The BBC news report about the bomb explosion at Vavuniya and the subsequent army retaliation had upset the Tamil delegates. Hector Jayewardene stepped in to defuse the situation. He read a government statement which said that there was a bomb explosion which killed 19 civilians and injured five. He said the report about the army killings were baseless rumour.

PLOTE representative Vasudeva informed the meeting that the army was attacking civilians in Vavuniya and Trincomalee. He said over 250 civilians had been killed.

Then he read the following statement:

We have stated in our response to the proposals made by the Sri Lankan Government delegation on the 16th of August 1985, that there was one matter of some considerable importance to which we proposed to refer in a separate statement and we do so herein.

As we have talked here in Thimpu, the genocidal intent of the Sri Lankan state has manifested itself in the continued killings of Tamils in their homeland. In the most recent incidents which have occurred during the past few days more than two hundred innocent Tamil civilians including young children, innocent of any crime other than that of being Tamils, have been killed by the Sri Lankan armed forces running amok in Vavuniya and elsewhere. It is farcical to continue peace talks at Thimpu when there is no peace and no security for the Tamil people in their homeland. We do not seek to terminate the talks at Thimpu but our participation at these peace talks has now been rendered impossible by the conduct of the Sri Lankan State which has acted in violation of the ceasefire agreements which constituted the fundamental basis for the Thimpu talks.

When Vasudeva finished reading the statement, Tamil delegates collected their papers and walked out of the conference room. Indian officials who were present were shocked. So were the members of the Sri Lankan delegation.

Varatharaja Perumal. courtesy TamilNet April 2, 2010

Indian officials tried to prevent the total collapse of the talks. They pleaded with the Tamil delegates who were preparing to leave for Chennai to stay in Thimpu. The ENLF delegates conveyed that information to their leaders who were assembled at the Kodampakkam hideout to which the ‘hot line’ was provided. The leaders ordered their representatives to come back. The delegates were told to tell the Indians that their leaders had ordered their return.

All ENLF delegates readily obeyed the order to return, but Varatharajaperumal, one of the EPRLF’s delegates, was hesitant. He told his colleague Ketheeswaran, “How can we go when the Indians are pleading with us to stay on.” Ketheeswaran conveyed that to the EPRLF leader Pathmanabha and Pathmanabha ordered through the ‘hot line’ for Varatharaja Perumal to return. “You come with the others. Else…” he warned.

Pirabha’s Statement

The Thimpu talks which kindled much hope thus ended in total failure. And as expected, the Jayewardene government launched a ferocious propaganda campaign. It blamed the Tamil militants for the collapse of the talks. It accused the Tamils of being intransigent and rigid. It said the only option available to the government was the military solution. And the army was unleashed to clear the border areas of Tamils whom Athulathmudali called ‘terrorist supporters.” Pirapaharan reacted sharply to the Sri Lankan government propaganda. He issued a statement in Tamil explaining the decision to stage a walk out. The following is the text:

We decided to attend the Thimpu talks because we did not want to hinder the honest and good-hearted efforts of the new Indian Prime Minister to usher in peace in Sri Lanka. We were aware that his efforts would not succeed. We knew the dictatorial and oppressive Jayewardene government was not interested in peace.

Prabakaran 1987

Yet we decided to accept the ceasefire and attend the talks. We thought that the talks would provide us the opportunity to tell India and the world about Jayewardene government’s oppressive actions and its unwillingness to offer a just and reasonable solution to the problems of the Tamil people.As we anticipated, Sri Lanka government did not submit a worthwhile proposal that dealt with any of the basic problems of the Tamils.

Jayewardene’s strategy is to trap us, the freedom fighters, in his peace net and make us slaves. We the Tamil Tigers are not prepared to get caught in this net.Sri Lankan state is trying to divert the attention of India and the world from its genocidal acts with the peace drama.

We are anxious that India should realize the destructive intentions of the Sinhala racists. Former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi knew that Jayewardene is a trickster and a deceiver.

The new Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi desired peace. He has evinced a personal interest in the Tamil people. He likes the Tamil people to live in safety and dignity. The Jayewardene government pretends that it is supporting his desire. It is trying to drive a wedge between India and Tamil liberation organizations. We hope that India would soon realize Sri Lanka’s strategy.Our desire is an independent Thamil Eela state. That desire is unshakable. We are fighting for that objective risking our lives. We believe that no other alternative would be a solution to the Tamils of Tamil Eelam.

We expect India which supports the freedom struggles of the oppressed people’s of the world to support the struggle of the people of Tamil Eelam. It may take some time for the people of India to extend their hand of support to us. We will keep struggling for that support.

Causes of Failure

Balasingham in War and Peace (Page 82) gives four reasons for the collapse of the Thimpu talks. The first was Romesh Bhandari. Balasingam says: “He did not understand the very fundamentals of the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka, nor could he grasp the contradictions underlying the perceptions and attitudes between the Sinhala and Tamil nations. His impulsiveness and impatience manifested in his expectation of easy and quick solutions to difficult and complicated issues.” This reimposes the assessment of Thondaman. As I indicated earlier, he told me Romesh Bhandari did not understand anything about the Tamil problem.

The second reason for the collapse of the talks was India’s intelligence agencies and officials. They adopted an assertive, master – servant approach. ‘Do as we tell you or be prepared to leave India.’ They were openly concerned with Indian interest. They were totally insensitive to the Sri Lankan Tamil interest.

The third factor was the Sri Lankan government’s approach. It wanted to make use of the talks to show the world that it was prepared for a political solution, but the Tamils were intransigent and inflexible. Its selection of the delegation, the stand the delegation took and the proposals it submitted were intended to deceive the international community and prepare the ground for the military onslaught on the Tamils.

And the most important factor was the failure of India and Sri Lanka to realize that Tamil freedom fighters had their own vision and were totally committed to their vision. India wanted to use the talks and the Tamil militant groups to achieve its national interests. Sri Lanka thought that it could crush the Tamil militant groups if it could drive a wedge between India and the Tamil militants.

Though they failed, the Thimpu talks was a watershed in the Tamil Eelam freedom struggle. Firstly, Sri Lanka and India recognized that the leadership of the Sri Lankan Tamils had passed to the liberation organizations from the political parties. They also implicitly recognized the armed struggle. This recognition furthered the legitimisation of the armed struggle of the Tamil people in the international arena.

Secondly, the Thimpu Declaration provided the basis for the alternate solution to an independent state of Tamil Eelam, the goal set by the Vaddukoddai Resolution of 1976,

Thirdly, the talks threw up Pirapaharan as the deciding factor of any solution to the Sri Lankan Tamil problem.

Next: Chapter 40. Deportation Emboldens Jayewardene

To be posted March 25

###