by T. Sabaratnam, May 31, 2004

Chapter 3

Original index to series

The Talk

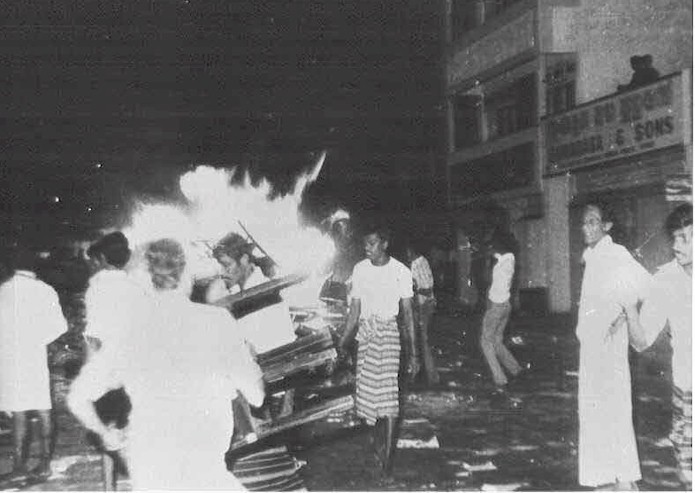

A burnt Tamil textile shop, July 1983

In the last chapter, I referred to the information that my friend in the Jathika Seva Sangamaya (JSS) gave me about the final solution. I also said that at that time I did not realize the actual meaning of that phrase. As a political reporter since I joined Lake House in 1957, and as one who concentrated on reporting and analyzing the developments connected with the ethnic conflict, I gave the phrase a political connotation. I realized its real import only after the eruption of violence on Sunday night, July 24, 1983.In Lake House, I have moved with several leading editors. One of them was the late Mervyn de Silva, who served as Daily News Editor and later as Managing Editor of the Lake House newspapers. After retirement, he published the Lanka Guardian and wrote a regular column, ‘Men and Matters,’ in the Sunday Island. In his column of 2 February 1992 he wrote, ‘At least a week before the savage eruption, there was talk of ‘something about to happen’… something nasty, of a ‘lesson to be taught.’

I wish to record here the explanation a Sinhala journalist friend gave me about the motive behind the burning of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981. He said, “We wanted to teach the Tamils that we can burn their property not only in Colombo and other Sinhala areas, but also in Jaffna.”

I am fully convinced that the nasty ‘something’ that was let loose on Sunday night, July 24 was the effort to teach the Tamils the lesson that they dare not challenge Jayewardene and the Sinhalese.

I gave in the last chapter my experience during the riots. I also said the aim of the riots was to destroy the economic, social, and professional base of the Tamils and reduce them to a weak, subject race. I also mentioned that one of the professional groups targeted for weakening was media personnel. I mentioned the names of some of those who were targeted. One of them was R. Sivagurunathan, former editor of Thinakaran and former president of the Working Journalists Association of Sri Lanka.

Sivagurunathan gave evidence before the Presidential Truth Commission set up by President Chandrika Kumaratunga under the chairmanship of former Chief Justice S. Sharvananda. Sivagurunathan, who lectured at the Law College in addition to his job as editor, claimed compensation for his burnt house and looted property. He said the assistance of Rs. 75,000 he received from the state was totally inadequate.

Sivagurunathan lived at Ramakrishna Road, Wellawatte, opposite the Ramakrishna Mission at the time of the riots. He was in Lake House with me on Sunday night, July 24 when disturbances commenced in Borella. Around midnight we received information that Anderson Flats in Narahenpita was under attack.

Now let us listen to the evidence Sivagurunathan gave the Presidential Truth Commission:

R. Sivagurunathan, Courtesy TamilNet

“I contacted my friend Tiruchelvam, who was working for another newspaper at the time. He told me that his neighbours’ houses were being attacked. When I called him again, Tiruchelvam told me that his house was being attacked by rioters. I had no contact with him after that. He now resides in Canada.

“That night, I contacted many friends on telephone, many of them were crying.

The next day I went to the Law College to give a lecture. At the Law College, there were only five students in my class. I sent them home. Then I walked to the bank and deposited the jewellery I had brought from home in the vault. When I came out of the bank, Pettah was burning. I walked to Lake House and tried to contact home. I could not do so.

I tried to contact Ministers A C S Hameed and M H Mohammed to get assistance, without success. I tried to go home but vehicles were not available. Curfew was declared at 2 p.m. and Lake House obtained curfew passes around 5:30 pm. I travelled home in an office vehicle. The driver dropped me at the top of Ramakrishna Road. He was scared to be seen by the Sinhala crowd driving a Tamil to his home.

“I walked towards my home. I saw a crowd burning heaps of household articles. When I went near my house, I met my neighbor Gunatilleke. He said, ‘I say, you are coming only now, everything is gone.’

I ran to my house. I saw all doors open and flowerpots thrown all over. Some parts of the house were burning. In one room, I saw clothes piled on the bed. I went in and found our veena underneath.

“I went next door. My neighbor, Mrs Gunaratne, opened the door and told me, ‘Mr Sivagurunathan, don’t worry they are safe with me.’ Then I felt relieved.

“All my belongings were burnt. I was able to save only my wife’s bridal sari and a few others. Other things were gone.

“I moved with my family to Ramakrishna Mission which was opposite our house. Mrs Gunaratne did not want us to leave. I left because I felt she might get into trouble if we remained.

“While we were at the Ramakrishna Mission we heard a rumor that the mission might be attacked. So we went to the refugee camp at the Saraswathi Hall. We were one of the first families that moved to Saraswathi Hall. Later another refugee camp was set up at Hindu College.

“In both the camps there were over 5000 people. The camps were crowded. Some days I slept under a tree. From the camp, I went on Thursday to see the house. Then it was completely burnt.”

The commission asked Sivagurunathan whether reconciliation between the Tamil and Sinhalese communities was possible after the riots. He said it was possible because the riot was not the spontaneous uprising of the Sinhalese people against the Tamils. He said it was engineered by certain forces that wanted to derive political benefit out of it. He said that was apparent from the fact that the people who went around burning houses had lists of houses they had to burn.

Curfew Delayed

The lists the rioters carried with them and the role UNP leaders and their thugs played were not the only reasons for the suspicion that the riots were state inspired. The fact that the declaration of the curfew was delayed till 2 p.m. was another major reason.

JR Jayawardene

Jayewardene could plead that he was not aware of the situation outside his residence and office. Jayewardene was fully briefed of the developing situation. He was told of the killing of Tamils and looting and burning of their property. A top policeman told me that Jayawardene was also told about the corpse of a Tamil found close to his Ward Place home. Police had told him on Sunday night itself that the situation was dangerous and had urged him to impose curfew.

Again, on Monday morning the police and his ministers begged Jayawardene to clamp a curfew. A well-attended conference of senior police officers was held at 6.30 a.m. on Monday 25 July on the third floor of the Police Headquarters in Colombo Fort. Inspector General of Police (IGP) Rudra Rajasingham presided. The conference decided to recommend to the president the need to impose a curfew and authorized the IGP to tell him that the police were prepared to enforce it. The IGP, I was told, conveyed that decision to the President. The President refrained from acting on the recommendation. He also refrained from giving any instruction to the police or the army about handling the riot.

|

| Tamil properties being thrown out of shops and burnt, July 1983 |

Ministers Thondaman, Festus Perera, Ronnie de Mel and K.W. Devanayagam told me that they had pressed Jayewardene on Monday morning when they met him at the Presidential Secretariat to declare curfew. The President did not act on it.

Ministers and police officials told me that the president was not shaken by the events. That was also the impression Thondaman gave me. Police officers who dealt with him that morning gave me a different view. They said Jayawardene was active and gave orders to the IGP and the Army Commander whenever the situation demanded and they added that those orders were promptly carried out. One of the glaring instances given to me was the action the IGP took when Jayawardene asked him to protect the wife of Acting Indian High Commissioner Abeyankar. High Commissioner G. K. Chhatwal was in New Delhi at that time and Deputy High Commissioner Abeyankar was acting for him. His residence was at Park Road.

Edward Gunawardena was the Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG) in charge of Colombo at that time. He was a loyal officer very close to Jayewardene. After retirement, he was appointed a director of Lake House. He published a novel, Blood and Cyanide, in which he wove some of the actual happenings during the 1983 riots. On pages 256 and 257, he gives in graphic detail the Abeyankar incident.

Gunawardene was in Narahenpita when the police Command Centre came up on the police radio network.

“Com. Centre to all officers and mobiles in South Zone. Proceed forthwith to the Park Road residence of Mr. Abeyankar, Acting Indian High Commissioner. Mrs Abeyankar is reported to be trapped in the burning house. I repeat. Proceed immediately to Park Road residence of Mr. Abeyankar, Acting Indian High Commissioner. This is priority number one.

South 1 (Superintendent of Police Colombo South) to Com Centre: Received. I am proceeding to the spot.

Task Force Mobile to Com Centre: Received. We are at the Wellawatte Station. Starting off. All roads are heavily congested.

South 2 (Deputy Superintendent of Police Colombo South) to Com Centre: I am near the Police Park. Can’t get through traffic. I am running to the spot with two PCs. A cloud of smoke is rising in the Park Road direction.

Alpha 1(IGP) is calling Com Centre

Com Centre: Come in Sir.

Alpha 1: I am on my way to Park Road with Alpha 2 (Senior DIG) in his car. Inform Presidential Secretariat accordingly.

South 2 calling Alpha 1: May I come in, Sir?”

Alpha 1: Come in South 2. I am receiving you.

South 2 to Alpha 1: I am at the spot, Sir. There is no fire in the High Commissioner’s house. Mrs. Abeyankar is safe. The smoke is coming out of Jim Rutnam’s house a fair distance away.

Alpha 1: Thank you South 2. Wait there until we arrive.

South 2: Received Sir.

As the IGP arrived at Abeyankar’s with his Deputy, Mrs Abeyankar greeted him with a smile. ASP Colombo South was there with his two PCs. The IGP thanked him once again for promptly responding to the situation.

Mrs Abeyankar, who served coffee to the IGP and his deputy, said she had not told anybody that her house was on fire, but had informed the Wellawatte police that there was fire close by.

A relieved IGP telephoned the President from the Abeyankar residence and briefed him of the facts.

Gunawardena’s account clearly shows that Jayewardene was aware of the situation. The situation in Colombo was terrible. On the roads loads of Sinhala office workers were traveling in lorries and other vehicles that belonged to their departments. Standing on the tailboards, they were shouting slogans like ‘Drive the Tamils away,’ ‘Kill the Tamils’ and ‘Victory to the Sinhalese.’

Around 10 a.m. Fr. Tissa Balasuriya , director of the Centre for Society and Religion, went out to Dean’s Road and waved at a military truck to send the Tamils who had gathered at the Church to a refugee camp. Linus Jayatilleke of the Nava Sama Samaja Party (NSSP) who saw it warned the priest not to hand over the Tamils to them. He told Fr. Tissa Balasuriya, “They are not from the normal army. They are government thugs. They will kill the Tamils.”

Around 10 a.m. Fr. Tissa Balasuriya , director of the Centre for Society and Religion, went out to Dean’s Road and waved at a military truck to send the Tamils who had gathered at the Church to a refugee camp. Linus Jayatilleke of the Nava Sama Samaja Party (NSSP) who saw it warned the priest not to hand over the Tamils to them. He told Fr. Tissa Balasuriya, “They are not from the normal army. They are government thugs. They will kill the Tamils.”

My colleagues at Lake House told me that many government politicians transported their thugs to Colombo in government-owned vehicles. Sri Lanka Transport busses were used for that purpose. Ceylon Electricity Board vehicles were also used. Vehicles from government departments and corporations were utilized. Army trucks were on the roads. Mobs cheered them, “Sinhala Hamudawata Jayawewa (Victory to the Sinhalese army).”

Police and army personnel were in league with the rioters. L. Piyadasa has recorded the following incident: “At the corner of Galle Road and Dickman’s Road, a unit of Jayewardene’s troops trained their weapons on six Tamils to prevent from escaping and got the Sinhalese ‘heros’ to batter them to death and burn their bodies.”

A burnt-out minibus, July 1983

Looting, arson and murders spread to Dehiwala, Kohuwala, Kotte, Nawala, Peliyagoda and other suburbs. By the time a curfew finally came into effect the Tamil houses and the property of the Tamils in the entire Colombo district were burning.

The factories of Indian industrialists were razed. Factories belonging to A Y Gnanam, the only Sri Lankan industrialist to have received a loan from the World Bank, the business chain belonging to the Maharajah organization and the Indian-owned textile mills of Hidramani Ltd, where more than 4,000 Sinhalese were employed, were gutted. K G Industries belonging to K Gunaratnam, a leading Jaffna Tamil businessman who owned several theaters in Colombo, were torched. Hentley Garments, one of the biggest garment exporters and several other large textile and garment factories were set on fire. Anything that belonged to Tamils, either Tamils of Sri Lanka or Tamils of Indian origin, was marked off for arson.

The Indian Overseas Bank and the Bank of Oman were set on fire. Most of the cinema theatres that belonged to Tamils in Colombo and its suburbs were razed.

The violence, according to victims and international news agencies, was vicious and bloody. My investigations revealed that the instruction given to the ‘gang leaders’ was to act ‘swift and sharp.’ They were given four hours – 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. – to complete the operation. The gang leaders started their destructive operation sharp at 10 a.m. and withdrew at 2 p.m. That happened in all parts of Colombo. The limited duration helped save some houses, especially those on the further end of the entry points.

Jayewardene was at the Presidential Secretariat on Monday morning and afternoon and went to the Army Headquarters in the evening to preside over the Security Council meeting. Bradman Weerakoon was there. Top police and army officials were also there. Weerakoon said the news about the prison massacre came in while the meeting was on.

Prison Riots

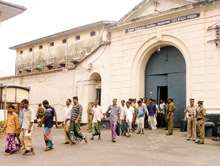

Entrance to Welidada Prison

Police knew about the Welikada Prison riots around 2.45 p.m. At that time, the following conversation was heard on the police radio network.

South 2 to South 1- There is a serious situation in the prisons. The Tamil prisoners are being killed. Mr. Janz is seeking police assistance. We can’t get there. The army is in control.

South 1 to South 2- If the army is in control, we had better keep off. We can’t afford to have a rub with the army.

South 2 to South 1- Received Sir, Roger.

Christopher Theodore Jansz was the Acting Prison Commissioner. Prisons Commissioner J. P. Delgoda was out of the country.

Trouble in the Welikada Prison started at 2:00 p.m. As the clock struck 2:00, 300 to 400 prisoners who were outside their cells ran towards the Chapel Section of the Welikada Prison, the high security jail in Sri Lanka. “Kill the Tamils,” they shouted. Some barked, “Kill Kuttimani.”

I interviewed three of the 19 who escaped this vile and inhuman massacre, the cold-blooded killing of prisoners in the custody of the State. I reconstructed the following account on the basis of the information they gave during the interview, the testimony given at the magistrate’s inquest and the evidence laid before the Presidential Truth Commission.

Welikada Prison is close to Borella junction where riots broke out on Sunday night. The prisoners heard throughout the night the shouting and the explosions from the burning buildings. “We knew something was happening but we did not know what it was,” said Manikkathasan, the military wing leader of the PLOTE.

Dr. Rajasunderam, Mr. Kuttimani and Mr. Thangathurai were among the 52 Tamil political prisoners murdered in government custody in a maximum security prison, July & August 1983

They learnt what the commotion was at about 8 a.m. Kuttimani passed on to them the news about the death of the 13 soldiers and the riots. Prison regulations permit the supply of newspapers to prisoners sentenced to death. Kuttimani, Thangathurai, Jegan, Thevan, Sivapatham Master and Nadesuthasan had been convicted for the Neerveli Bank Robbery of 1981. They had appealed against the conviction.

By about 10 a.m. they felt the tense atmosphere inside the prison.

Most of the 72 Tamil prisoners were locked up inside the two-storied cross-shaped building called the Chapel Section. It had four wings A, B, C, and D. These wings on the ground floor were marked A3, B3, C3 and D3. Kuttimani and other five convicted prisoners, Thangathurai, Jegan, Thevan, Sivapatham Master and Nadesuthasan, were locked up in separate cells in the front section of B3. In D3 29 Tamil prisoners detained under PTA were kept. They were mostly young boys taken in on suspicion and who, according to Jansz, were due to be released soon. In C3, there were 28 more Tamil PTA detainees. Douglas Devananda, Manikkathasan, Robert, Paranthan Rajan, Panagoda Maheswaran, Baskaran, Thevakumar, Jayakody and others were in that section. In A3, dangerous criminals and those who had tried to escape were housed. Sepala Ekanayake, convicted for hijacking an Alitalia aircraft, was in that section. The space between the four wings is the lobby and iron doors stand at the entrance to the passage to each wing. Two guards are on duty near each iron door. In the two upper floors, about 800 ordinary prisoners are housed.

Nine other Tamils were kept in the Youthful Offenders Building (YOB), a separate building a little further away. They were: Dr. V. Tharmalingam, Kovai Mahesan, Dr. Rajasuntharam, A. David, K. Nithiyananthan, Fr. Singarayar, Fr. Sinnarasa, Rev. Jayathilakarajah and Dr. Jayakularajah. They were kept separate in the another building because they were professionals and considered not dangerous.

Around 2 p.m. the Tamil prisoners heard hysterical shouts. They herd the chant, “Kill the Tamils,” “Kill Kuttimani,” and “We will drink their blood.” Leading the screaming crowd was a prisoner whom Kuttimani had treated with affection. Physically he resembled Pirapaharan, who was called ‘Thamby‘ [little brother] by all. Kuttimani started calling that prisoner Thamby and other Tamil prisoners also called him Thamby. He was one of the prisoners who served food to Tamil prisoners.

‘Thamby’ led the crowd to Kuttimani’s cell.

A group of about 25 men carrying knives, crowbars, axes and iron bars with sharp points led the turbulent crowd. They opened the iron door leading to the passage to B3 and banged the cell doors of the six TELO convicts with the weapons they carried. They unlocked the cell doors with the keys they had brought and pushed them open. The Tamil militants fought back. They fought with bare hands. Kuttimani, an expert in karate and boxing, dealt them shattering blows. He hit back with his hands and legs. But he could not hold on for long. He was outnumbered. They pushed him. He fell. They clubbed him and then cut him with the knife.

Then they dragged him to the lobby. They put him in the kneeling position. Then they gouged out his eyes with pointed iron bars. The crows jeered, shouting, “We have plucked the eyes which you wanted to see the birth of Eelam.”

The reference was to Kuttimani’s statement from the dock made after he was sentenced to death. He said that his last wish was to donate his eyes to a blind Tamil boy so that his eyes would see the birth of Eelam.

A prisoner then ran up to Kuttimani, who was still in his kneeling position. He raised the drooping head and pulled out his tongue. He cut it with a knife. He popped it into his mouth and danced saying, “I have drunk Tiger blood.”

Then they killed him.

After killing the six convicted prisoners, the mob leaders ran to D3 which housed the 29 PTA detainees. They attacked them. They missed Mylvaganam, a 16-year boy who, thoroughly frightened, crouched in a cell. A jail guard spotted him and stabbed him to death.

Two able bodied detainees in D3 watched these evil acts. Manikkathasan peeped through the ventilation hole and watched what happened in the compound. He saw the crowd running towards the Church Section and the piling of the bodies in front of the statue of Buddha. Robert’s (Kandiah Rajendran) cell was close to the lobby and he gave a running commentary to the others about the events that took place in it. Manikkathasan lived to tell the world the things he saw. Robert was killed during the second prison massacre. His running commentary is still remembered by those who survived.

Robert also related to others a discussion that took place at the end of Monday’s massacre. The gang leaders wanted to finish off the job by killing the remaining Tamil prisoners. There were 28 in C3 and nine in YOB left. A jail guard told them, “Today, it is enough.”

Prison officers have told the inquest and the Presidential Truth Commission their side of the story. Leo de Silva, Superintendent, Welikada Prison, told the inquest that around 2.15 p.m. he heard the alarm and ran to the Chapel Section. About 300 to 400 prisoners stood blocking the entrance to the lobby, while a small group attacked the Tamil prisoners. He said he was prevented from going in. He heard blows falling on human bodies and the scream of the victims. He summoned the army unit stationed outside the prison. Jansz said he also ran to the Chapel Section and could not do anything as he was blocked. He saw the soldiers coming in and they also were not in a position to do anything. Jansz said, finding that the jail guards and the army were unable to do anything, he went to the Borella police for help. The officers there told him they had no manpower. Then he met DIG R. Suntharalingam who pleaded inability to help. Suntharalingam told him that he was about to attend the Security Council meeting. He undertook to do all that he could do and mention the matter at the Security Council meeting. Jansz then went to Colombo Hospital and sought help to transport the injured to the Accident Ward.

While Jansz was away, Leo de Silva said most the prisoners started going away and he entered the lobby. From there he saw several bodies lying in the corridors of B3 and D3. Leo de Silva, with the help of some guards and other prison officers, brought the injured persons to the lobby. Robert saw some of the guards and attackers trampling on some of the injured persons who lifted their heads and asked for help. The injured persons were then dragged from the lobby and piled in front of the Buddha statue. Manikathasan said that there, too, the persons who appeared alive were trampled on.

When Jansz returned to the prison, he found a police party waiting outside, as the army had refused to let it in. He spoke to the police party and they were reluctant to enter defying the orders of the army. Jansz went to his office and tried to contact Army Commander Tissa Weeratunga who had returned from Jaffna in the afternoon. Janz failed to contact him or any of his deputies. He was told they were with the President at the Army Headquarters where the Security Council was meeting was on. Jansz rang DIG Earnest Perera who asked him to come to the Police Headquarters.

Jansz went to the Police Headquarters with Leo de Silva, leaving Welikada in the charge of their assistants. From there he contacted Weeratunga who gave permission for the police to enter the prison. While Jansz was at Headquarters, IGP Rudra Rajasingham and DIG Suntharalingam returned from the Security Council meeting. Suntharalingam told him that the Prison Massacre had been discussed at the Security Council meeting.

When Jansz returned from the Police Headquarters the time was around 5 p.m. By that time the bodies of the injured persons that were lying in front the Buddha statue had been thrown into a truck that was to take them to the Accident Ward of the Colombo Hospital. Manikathasan said he heard jail guards hitting the injured inside the truck. Investigations have revealed that one or two of the injured were alive inside the truck and died of suffocation or were killed on the way to the hospital.

The Prison doctor, Dr. Perinpanayagam, was summoned only after Jansz returned from the Police Headquarters and he ordered the injured to be taken on a stretcher to a room where he conducted the examination. The examination went on till about 10 p.m. Dr. Perinpanayagam found all dead.

As Jansz had made arrangements to send the injured to the Accident Ward and the Prison doctor had pronounced them dead, the 35 bodies were sent to the Medico-Legal Morgue at the Colombo General Hospital. Then the issue about the disposal of the bodies arose. Since Prisons fell under the Justice Ministry, Jansz consulted the ministry secretary, Mervyn Wijesinghe, who decided to ask for a magisterial inquest.

He informed Colombo Chief Magistrate Kirthi Sirilal Wijewardene to hold an inquest and Judicial Medical Officer (JMO) Dr. M. S. L. Salgado to perform the post mortem examination. The post mortem examination and inquest were held Tuesday night. The inquest proceedings were concluded in the early hours of Wednesday.

The magistrate entered a verdict of homicide from a ‘general state of unrest.’ He then cleared the prison officers and army officers of complicity or neglect of duty. He said they could not do anything as they had been over-powered. He then ordered the Borella police to pursue investigations and produce the suspects before him.

Vital questions, such as who originated the riot, who led it, and whether some jail guards were involved in the massacre, were not raised during the inquest. Names of those who led the attack were not asked or mentioned. Tamil prisoners in C3 were not asked to testify.

Tamil prisoners in C3 were in a position to name some of the attackers and the politically influential jail guards who instigated the riots. They aver that the prison riots were part of the overall attack on the Tamil community. The army was in league with them. They say not even a warning shot was fired. Jansz’s testimony seemed to support the Tamil position.

The magistrate released the bodies to the director, CID, for disposal in accordance with the Emergency Regulations proclaimed a week earlier. Shortly before dawn on Wednesday, July 27, the 35 bodies wrapped in white cloth and taken in a prison truck to Kanette. There they were thrown into a large pit by the prisoners who went in the truck. Logs of wood were thrown over the bodies. Cans of petrol was sprinkled and a fireball made of cloth was thrown on the pile.

The flames from the pyre jumped skywards reddening the rising sun. Sri Lanka has been bleeding red since then.