by T. Sabaratnam, April 23, 2005

Chapter 43

Original index to series

Original Chapter 44 [renumbered from Chapter 42]

In 1985 the Jayewardene – Athulathmudali regime continued its strategy of mass arrests, torture, massacres and forced evacuations, thus strengthening the Tamil will to fight back and widening and deepening the Tamil militant groups’ recruitment base. In April, it also added the new Muslim factor, complicating further the ethnic conflict.

Mass arrests proved to be a strong factor that promoted instability among almost all Tamil families in the northeast. These arrests made it a problem for the families to keep young boys with them. The army had made it a habit to cordon off a single village or a group of villages, announce through loudhailers that all males between 18 and 35 must assemble in public places and take hundreds of them for interrogation. Some of those arrested were tortured and released. Some never returned.

In my visits to Jaffna and Trincomalee during this period, I heard from several parents that they preferred to send their sons abroad or to the LTTE because they would be safer there than being with at home. Many spoke about Jayewardene’s government and its army with hatred.

Mass arrests were the order of the day during January and February of 1985. On 2 January, security forces cordoned off the villages of Alvai, Thikkam, Navalady and Irupiddy in Vadamarachchi division of the Jaffna peninsula, ordered through loudhailers all males between 18 and 35 to assemble in public places and took 200 persons for questioning. Three days later, 5 January, they arrested 500 persons in the coastal areas of Jaffna city. In Batticaloa, they arrested 1,000 youths, in Trincomalee 2,000, in Vavuniya 1,000, in Akkaraipattu 400 and so on. In the first quarter of the year, the security forces conducted 52 cordon and search operations and took for questioning over 10,000 Tamils.

Mass arrests were the order of the day during January and February of 1985. On 2 January, security forces cordoned off the villages of Alvai, Thikkam, Navalady and Irupiddy in Vadamarachchi division of the Jaffna peninsula, ordered through loudhailers all males between 18 and 35 to assemble in public places and took 200 persons for questioning. Three days later, 5 January, they arrested 500 persons in the coastal areas of Jaffna city. In Batticaloa, they arrested 1,000 youths, in Trincomalee 2,000, in Vavuniya 1,000, in Akkaraipattu 400 and so on. In the first quarter of the year, the security forces conducted 52 cordon and search operations and took for questioning over 10,000 Tamils.

“They were all taken in on suspicion and were released after interrogation,” National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali reported to Parliament.

When asked about the arrest of such large numbers, he answered, “Our problem is to eliminate the terrorists. How are we to identify the terrorists? How are we to sort out the terrorists from loyal citizens? We know no other method than screening the entire population.”

Athulathmudali ordered this screening and, in the process, he instilled in the minds of every Tamil that he is a suspect. Screening also planted in the Tamil mind another dread; the fate that would befall those arrested between arrest and release.

For Athulathmudali screening was a simple operation. ‘Taking in, questioning and releasing’ was how he described it. The manner in which arrests were carried out, the way the questioning was done and the state in which the arrested were released were the problems that disturbed the Tamil people.

Mahendra Kesivapillai was a 23-year-old second year science student at Jaffna University. He was with his parents in the East during the 14 January Thai Pongal festival, the harvesting celebration Tamils celebrate as a family unit. He went to the Batticaloa police station to obtain a police pass to return to Jaffna University to attend lectures. Officers of the Special Task Force (STF) took him in for screening, shot him in the left leg, then took him to the Kaluwanchikudi Commando Camp for questioning where he was severely beaten. He was then taken to the Batticaloa Commando Camp.

STF troops in riot gear, 2002

“I was told I was a terrorist. I was also told that I would be released if I admitted that I was a terrorist and was travelling to Jaffna for training. I denied those accusations and told them that I was a university student,” Kesivapillai said in an affidavit submitted to Amnesty International.

Kesivapillai’s affidavit described the nature of the questioning procedure he was put through.

“My hands were tied behind (me) …a rope was fastened to the hands and the other end of the rope that was thrown over the wooden beam in the roof. The rope was pulled and l was made to hang from this rope.

“Chillie powder was thrown into my eyes. My clothes were taken off and chillie powder rubbed onto my body and genitals. They placed nails on the soles of my feet and started hammering the nails with a plastic pipe. They rubbed chillie powder into the wounds on the soles of my feet.

“I was hung like this from 8 pm till 12 midnight. The following day I underwent the same treatment… I was hung up in the same manner and beaten from 11 a.m. till about 4 p.m. I was also burnt on my buttocks with a heated metal rod… When they released me from their treatment I was unable to move my hands or my feet.”

A week later, Kesivapillai was released and taken to Batticaloa Hospital. The doctors found that the nerves of his hands were affected due to prolonged hanging. He was hospitalized for three months and 20 days. Even after treatment he was unable to use his right hand. He was immensely handicapped and had to learn to write with his left hand.

Doctors who treated Kesivapillai at Batticaloa Hospital told the Citizens Committee that he had been subjected to unbelievable cruelty. They said he had many burn marks on his buttocks and arms. Two bones in his arms had been so badly damaged that he would never recover the use of his arms.

Kesivapillai’s horrifying story was only one of the several reported by Amnesty International.

Prince Casinader, 1925-2018

Prince Casinader, Chairman of Batticaloa Citizens Committee, told a seminar on human rights held in Colombo in 1985 that young men picked up by unmarked commando vans had disappeared. He told the seminar, “Last month unable to trace three of my school boys, I went in desperation to the mortuary. I saw three horribly mangled bodies with smashed skulls. I don’t know who they were, poor wretches, but they were not my boys.”

Foreign correspondents who visited the northeast in 1985 recorded incidents of torture during questioning. Trevor Fishlock reported in the London Times of 2 January 1985: “Hospital staff in Jaffna had seen “…many victims of army beatings. Typically boys emerge from interrogation and spells in custody with multiple bruises caused by thrashings with PVC pipes filled with sand. Some have heel fractures, having been suspended and beaten on the feet. A doctor said: ‘I see about five of these cases a week, but remember that many victims do not seek treatment because they are afraid or because it is impossible to travel’.”

“Those most at risk are young men, between the ages of 17 and 25, who are members of the Tamil community and have been arrested under the 1979 Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). Tamil women are also known to have been tortured,” Fishlock reported.

Torture during questioning was nothing new to the Sri Lankan army and the police. It was, for them, normal questioning procedure. It was first widely used during the first JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna) insurrection of 1971. I saw several Sinhala youths tortured in police stations which I visited during that time. I also heard blood-curdling stories of torture from the victims themselves.

Torture of Tamil youths commenced on a large scale with the arrest of 42 members and supporters of the Tamil Manavar Peravai (Tamil Students League), on 9 March 1973. Before that individual youths like Sivakumaran and Satiyaseelan had been tortured, but graphic accounts of the methods of torture became public knowledge after the arrest of the 42 youths.

The 42 youths were first kept in the Jaffna prison. They were then transferred to Negombo and then to Welikada. They were taken from the prison to the Fourth Floor of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Colombo for investigation. Inspector Bastiampillai was in charge of the investigating team. Police officers Perambalam, Selvanayagam and Banda assisted him. The focus of the investigation was to find out the names of the members and supporters of Tamil Manavar Peravai.

Information about the torture was leaked to Federal Party leaders and Tamil newspapers by the relatives of the victims. Amirthalingam placed some information in parliament. The youths were asked to remove their cloths on entering the investigation room. In some cases, pubic hair was singed. Mavai Senathirajah told me he was asked to lie down face downwards on a long table and was severely beaten. Big-made Mavai told me that he was beaten with wooden planks till he fainted. Mavai, now a member of parliament, shuddered when he related the treatment he received to me.

Senathirajah, 2001

Several Tamil youths were arrested and tortured again in 1975 following the murder of Alfred Duraiappah. Bastiampillai was still in charge of the investigation. The focus this time was Alfred Duraiappah’s murder, the TNT and its military leader, Pirapaharan.

Pirapaharan was the focus again in 1979. Brigadier Tissa Weeratunga, who was mandated by President Jayewardene to eradicate terrorism before the end of that year, 1979, adopted torture and slaughter of Tamil militants and their associates to draw out information and to eliminate the militants. C. Pushparajah, the founder president of the Thamil Ilaignar Peravai (Tamil Youth League) was one of those who was tortured. He has recorded his ordeal in his book Eelam Struggle: My Evidence, an autobiographical work published in Tamil in 2004. He says:

I was arrested at 5pm on 5 October 1979. I was taken to the Joint Army-Police Command office in Old Park, Jaffna. Inspector Karunaratne assaulted me while I was entering the office. Others who were present there also joined in the attack. Karunaratne caught me by my hair and dragged me inside the special room (known as the Meat Stall) built outside the Residency.

I was frozen with fear when I saw the things inside that room. I saw ropes hanging from the roof. Those were the ropes used to lift people up. I also saw different types of batons and wooden planks used to beat the people. There were also sacks, needles and iron bars used for torturing people. I noted telltale marks of blood on the walls and the floor.

I was asked to stand leaning on a wall. They securely tied both my hands. Then they hit me on my chest, stomach, sex organ and my legs. Karunaratne then swung towards me holding a rope and hit on my stomach with the boots he was wearing. When he hit me the second time I purged and collapsed, unconscious.

When I regained consciousness and opened my eyes, I asked the man whom I saw, the direction to the washroom. He got another person to help. I washed the pants and myself and wore the wet pants again. I could not move my limbs. My whole body was aching.

I was taken to another room. I saw Eelaventhan (now a member of parliament) seated on a chair. We recognized each other. We whispered to each other. Seeing that I was in wet trousers Eelaventhan gave me the extra verti he had. I wore it. They gave me bread to eat. Eelaventhan, due to his sickness, was allowed to get his meals from home. He gave me a portion of the curries. I ate the bread with that.

While we were talking, Karunaratne came. He asked me, “Who gave this verti?” I pointed to Eelaventhan. He shouted at him. He ordered him to stand static for two hours. He threw out Eelaventhan’s dinner. I felt pity for Eelaventhan. He struggled hard to stand for two hours without moving.

Then I was taken to the Meat Stall. Karnaratne tickled me, pinched me on my cheeks, poked his fingers into my stomach and made fun for some time. Then he asked: “Where do Tigers stay in Vavuniya?” I replied: “I don’t know.”

The rope descended from the roof. My hands were tied on to it. They pulled the other end of the rope. I went up. I was hanging from the rope. While I was dangling from the rope Karunaratne said: “Now tell the truth before we bring the man who saw you talking to Pirapaharan at the Vavuniya bus stand.” I replied, “I must know to tell you. I don’t know.”

They beat me all over the body with sticks and poles and raised me a little more. They left, leaving me hanging. I felt that my shoulder was tearing due to my weight. The pain was unbearable. I writhed. I shouted. I was brought down at 11 pm and pushed into a room and asked to sleep.

The room was full of youths. One of their hands was tied to an iron pipe nailed to the wall. My hands were not tied. I found a corner and slept.

When I woke up the next morning, I found that most of the people inside the room were from Valvettithurai….

During the daytime on the second day, I was asked to do physical exercises. I heard from others that was to prepare me physically to withstand the torture in the night.

Torture on the second night was different. First, I was questioned. I was asked about Pirapaharan, his training camps in Vavuniya, about the whereabouts of Pathmanabha, about Kannadi Camp and so on. When I said I don’t know anything about these matters I was taken out and cold water was poured on me. Then two persons held my eyes wide open and sprinkled chillie powder in them.

I was tortured like this for over ten days. Then I was sent to the Jaffna prison.

Hundreds of similar accounts are available in the reports of human rights organizations like Amnesty International.

Amnesty International’s File on Sri Lanka’s Torture published in October 1985 has classified the torture types thus:

- prolonged hanging upside down while being beaten all over the body, sometimes for the duration of one night and sometimes with the head tied in a bag in which chillie were burning, making the victim feel close to suffocating;

- prolonged beatings especially on the soles of the feet while lying stretched out on a bench or while hanging by the knees from a pole;

- beatings on the genitals and other parts of the body with sticks, batons and sand-filled plastic pipes;

- insertion of chillie powder in the nostrils, mouth and eyes and on the genitals;

- electric shocks;· insertion of pins under fingernails and toenails and in the heels;

- insertion of iron rods in the anus;

- burning with cigarettes;

- mock or threatened executions.

Apart from these some army camps used innovative torture methods, Amnesty reported.

A young man arrested in August 1984 for allegedly being in possession of “subversive literature” stated in an affidavit that on arrival in Panagoda Camp:

“…I was put into a dark room, stripped of all my clothes and made to lie on the floor. My hands and feet were chained and large spikes were inserted into my body. .. I was assaulted with machine guns, iron rods on the knee joints, neck regions, close to the eyes, on the feet and almost all parts of the body…! I was bound with chains on the legs and let down a deep well and then pulled up.”

In another case, a detainee in the Mankulam Army Camp was given electric shock. His affidavit published by Amnesty International says the incident occurred in June 1985.

“While questioning me he now and then placed on my leg a device which made me feel that 1 was subjected to an electric shock. This he did five times. Every time…my whole body shook violently and I was in a state of shock. The device appeared to be about two and a half feet long and pipe-shaped, black in colour. At one end, there was a coiled spring. It was this part that was applied on my body. At the other end there was a switch which was pressed every time it was applied…”

Massacres

Massacres of civilians and evacuation of the Tamils from their traditional villages in the eastern province disturbed and angered the Tamil people even more than mass arrests and torture. The massacre that occurred on 15 January 1985 and the government claim that the victims were terrorists intensely hurt the feeling of the Tamil people.

National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali announced on 15 January that 52 terrorists who were on their way to attack Sinhala villages had been ambushed and killed. He lauded the Air Force for mounting a preventive attack. The national media flashed Athulathmudali’s announcement and projected it as a major achievement of the Air Force. Sinhala people were thrilled.

The truth was different. Thai Pongal, the festival of harvest, which falls on 14 January, is traditionally celebrated by the Tamil farmers as a day of thanksgiving to the Sun, the Giver of Energy. They do the pongal (boiling of rice with milk) using freshly harvested rice. The next day they celebrate the maddu pongal, the festival to thank the cattle for providing the organic manure – cow dung – and for helping to plough and thresh paddy.

Some of the 2,000 families that were driven away by the army on Christmas eve in 1984 from the ancient Tamil villages of Kokkilai, Kokkuthoduwai, Karnatukerni, Nayaru, Chemmalai, Kumudumunai and Alambil in the Mullaitivu district and were living in refugee camps at St. Peter’s Church, Vattapalai Amman Temple, Vidyanantha College and Vattapalai Roman Catholic School in Mullaitivu town decided to return to their villages to harvest the rice they had sown before they were chased away and to celebrate Thai Pongal in their homes.

These families trekked back to their villages in small groups. They went back against their advice, refugee camp officials told Tamil journalists and human rights groups.

Soldiers at one of the string of checkpoints placed around the Tamil villages to prevent the villagers from returning to their homes noticed these groups. They alerted the newly established Weli Oya Brigade Headquarters which rushed reinforcements and summoned the Air Force. Low flying helicopters mowed down the civilian farmers and army reinforcements sprayed bullets on them.

Athulathmudali claimed that 52 ‘terrorists’ had been killed. The number killed was actually higher. A survey carried out in the refugee camps showed that 131 persons were missing; 37 of them women. The survey report gives the names and ages of most of the missing. One of them was V. Muthulingam, aged 12 years. He had gone with his parents to help them in the harvest.

Tamil journalists pointed out these facts to Athulathmudali. He amended the classification of the dead from ‘terrorists’ to ‘separatists,’ but insisted that they had no business to be in the prohibited area. He said, “That was a prohibited area and all those who enter are terrorists.” Saturday Review and the Tamil papers published the correct position.

The Anuradhapura massacre, the second LTTE attack on Sinhala civilians, (see Chapter 32 for the context of the Anuradhapura massacre) which occurred on 14 May 1985 spewed another bout of civilian massacres in the east. (see Saturday Review of 18 May 1985). In the following three days two massacres were carried out. The first was the Kumuthni massacre. Forty-eight civilians who travelled in the ferry Kumuthini on 15 May from Delft to Jaffna were killed by naval personnel. Two days later at Natpattimunai, the Special Task Force killed 42 civilians. (Chapter 33).

Bacre Waly Ndiaye

The Natpattimunai massacre was raised by the Indian delegation at the meeting of the Commission on Human Rights in 1986. The meeting appointed Bacre Waly Ndiaye [now the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ representative in New York] as the Special Rapporteur to report on that matter. He reported to the commission after his visit to Sri Lanka:

On 17 May 1985, 23 young men from Naipattimunai, Amparai district, were allegedly arrested by Special Task Force (STF) personnel from Kallady camp and made to dig their own grave. Subsequently, they were allegedly shot. Mr. Paul Nallanayagam, President of the Kalmunai Citizens’ Committee, was arrested and charged with spreading rumours and false statements after speaking to foreign journalists about the incident. During his trial before the Colombo High Court in mid-1986, a lot of evidence emerged about the disappearance of the 23 young men, but no further action against those responsible has been taken since. Paul Nallanayagam was acquitted of all charges on 17 July 1986. It was reported that the Government of Sri Lanka did not take any action and that the official position remains that none of the disappeared had been arrested. Although a lot of evidence was available at the time about the arrests and subsequent disappearances by the STF, the police did not make any further attempts to investigate the incident.

The Kumuthini massacre was not investigated either. In the Trincomalee district the army, airforce and the newly established Home Guards were directly involved in the retaliatory attacks that followed the Anuradhapura massacre. Those events also were not investigated.

Rajan Hoole, in Sri Lanka: Arrogance for Power (Pages 331-335) has painstakingly reconstructed these events in detail. He made use of the TULF document prepared by former Member of Parliament for Muttur A. Thangathurai at the request of Rajiv Gandhi, a document Thangathurai’s brother, Dr. A. Pakiathurai, gave to Hoole and of newspaper reports for his effort.

The army started the attacks on the Tamils of the Trincomalee district on 23 May. It killed eight Tamil civilians, including S. Gangatharan, the 30-year son of Trincomalee Civilian Committee president S. Sivapalan, in Nilaveli. Gangatharan’s wife, Saraswathy, recalled to AFP (Agence France-Presse) correspondent Allen Nacheman, how Gangatharan was killed.

Saraswathy said two men went to their gate. “One of them was in uniform, I thought he was a soldier,” she said. “I saw them talking. The soldier put his gun to my husband’s chest and fired.”

“He fell backwards. I ran towards him. The soldier pointed the gun at me. I grabbed the two children and ran.”

Gangatharan’s fault was that he supported the TULF. The rest were killed when soldiers fired into their homes. The intention of this indiscriminate firing was to drive away the Tamils from Nilaweli, a beautiful tourist resort.

Next day, 24 May, Air Force personnel shot dead nine Tamils at Pankulam, a Tamil village west of Trincomalee. An elderly gentleman, Thamotherampillai, his wife Parameswari and other members of the family, sixty-five-year-old Abiramy Pandiaiya, Valli Marimuthu and two-year infant Jayabalam were among the slain.

Sinhala Home Guards, established under government’s militarization scheme, went into action that day. At Muttur in the Kottiyar Bay Division, they attacked Tamil civilians. They also killed two Tamil civilians from Kankuveli who went to Dehiwatte junction to do their marketing. Their bodies were not recovered.

On 25 May, a father and his 12-year-old son, who went from Lingapuram in Allai to Kanguveli to invite their relatives for a family function, were cut to death by Sinhala Home Guards and buried near Kanguvelikulam.

On 26 May, Sinhalese Home Guards from Mihindupura burnt down 40 houses of Tamils in Poonagar in Ichchilampathi. In Colombo, Defence Ministry announced that Tamil terrorists had burnt down 40 Sinhala houses at Mihinduura, an example for the twisting of facts by the Defence Ministry. On the same day, four Tamils from Lingapuram in Allai who went hunting did not return. Tamils accused the Sinhala Home Guards on duty along the Allai – Kanthalai road of killing them. On that evening, soldiers shot dead three Tamil youths in the Koonithivu lagoon in Muttur.

On 27 May, Sinhalese Home Guards stopped a Ceylon Transport Board (CTB) plying on the Batticaloa – Muttur road near Mihindupura and ordered Pushparaja, the driver, and the seven Tamil passengers to get down. They were lined up and shot. Krishnapillai, one of the passengers, escaped with injuries. The bodies of the other six were heaped and burnt.

According to the list prepared by Hoole, at least 42 Tamil civilians were killed by the security forces and the Home Guards during the eight days preceding the Tamil militant attack on Mihindupura and Dehiwatte, two Sinhala villages in the Allai colonization scheme in the Trincomalee district. About half the number of Tamil deaths was due to the Sinhala Home Guards. The Home Guards were also responsible for the burning of several Tamil houses.

Remembering the Vaddakkandal, Mannar Massacre of at least 52 civilians by 200 Sri Lankan military personnel based in the Thallady Camp on 30 January 1985. Tamil Guardian 30 January 2017

The government booklet Massacres of Civilians lists the attack on Mihindupura and Dehiwatte on 30 May as the third civilian attack by the Tamils. It says that five Sinhalese settlers were shot dead by armed terrorists. The shooting was done by TELO. The attackers told Sinhala civilians of those villages that they were punishing the Home Guards responsible for attacks on Tamil civilians and their property.

The shooting of the five Sinhala Home Guards was portrayed as an attack on Sinhala villages and made use of to mount a massive operation against the Tamils and ancient Tamil villages in the Trincomalee district. Tamil National Alliance Member of Parliament R. Sampanthan, who was leading the campaign for the return of the Tamil people to their former villages, told Parliament in 2002, after a visit to Kiliveddy, that signs of the Jayewardene government’s ‘terror’ are still visible in the once prosperous Kiliveddy, a village almost erased from the face of the earth in just two days. He said,

“The burnt houses, the rusting frame of Paddy Stores and the ruined hull of the Milk Collection Centre are stark reminders of the former prosperity of the area against its present penury.” [probably a quote from TamilNet]

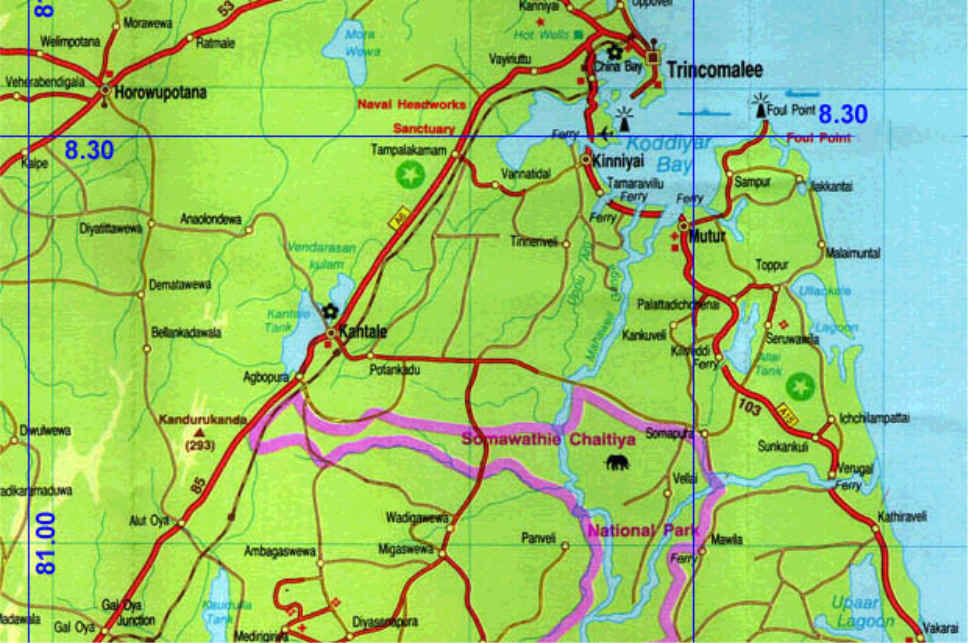

Kiliveddy is a very old Tamil village that lies about 85 kilometers north of Batticaloa on the Batticaloa-Trincomalee coast road. The predominantly Sinhalese colony villages of the Allai scheme lie south of it. Dehiwatte and Neelapola are also Sinhala colonies that lie northwest of Kiliveddy.

The attack on Kiliveddy commenced at 8.30 pm on 31 May 1985. A police party and Home Guards from the Sinhala village Serunuwara entered Thanganagar in Kiliveddy South Bank, burnt about 50 houses and took away 37 persons including women. They were first taken to the police station and driven towards Kanthalai. Thirty-six persons were killed and burnt at Sambalpiddy past the Mahaweli Bridge on the Allai-Kantalai Road. Rasiah alias Sinnavan escaped with gun shot injuries. He said he ran into the shrub and found his way to Trincomalee.

On the same night, most of the others fled the village and took refuge in Pachchanoor, Thoppur and in Trincomalee town. Some, mostly the old and infirm, elected to stay back thinking that they would not be harmed.

They were all killed the next day, 1 June. The attackers that day were from Dehiwatta, the village where Home Guards were shot dead by TELO fighters on 30 May. Around 2 pm a mob led by soldiers, policemen and Home Guards invaded Kiliveddy. Mylvaganam Kanagasabai, Inquirer into Sudden Deaths of the area and uncle of Thangathurai, who was seated under a tree talking to someone saw the menacing crowd and hid behind a haystack. The crowd pulled him out and shot him dead. They also killed nine others, including four women. The slain women were: Kamala Rasiah, wife of the person who escaped the previous night with gunshot injuries, and her daughter and Raja Rajeswary Ammal, wife of the local Hindu priest Subramaniya Sharma and her daughter Prasanthi.

The mob torched about 125 houses and took away 13 persons of whom three were old couples, five middle aged men and two young women. They were taken to Dehiwatte. The mob stripped all the eight men and shot them dead. One body was tied to a tree, naked. The young women were raped.

Thangathurai, who was then in Trincomalee, spoke to Simon Winchester from London Times who was there on an assignment and the Kiliveddy massacre received world-wide publicity. Athulathmudali denied the story, but his denial was not taken seriously. Thangathurai fled to Tamil Nadu when he got a tip-off that Athulathmudali had ordered his arrest ‘for spreading false rumours’!

The next day, 2 June, Home Guards stopped the Trincomalee- Point Pedro bus near the 10th Mile Post and took it into the jungle. They shot dead 13 passengers including women. In the next two days, 3-4 June, a massive operation was launched to drive away the Tamils from all the villages in the area between Kiliveddy and Muttur. Soldiers and Home Guards attacked several villages killing about 35 persons. Around 200 persons are missing.

Human rights organizations that studied the impact of this operation have reported that over 1,000 houses had been burnt. They have also reported that over 2,500 persons had sought refuge in Muttur and over 1000 had fled to the Batticaloa district.

The villages that were uprooted were: Menkamam, Kanguveli, Pattitidal, Palathadichenai, Arippu, Poonagar, Mallikaitivu, Peruveli, Munnampodivattai, Manetchenai, Parathipuram. Lingapuram, Itchilampathai, Karukkalmunai, Mawadichchenai, Muthuchenai and Valaithoddam.

Hoole, who took a close look at the events in the Trincomalee district from 23 May to 4 June, has recorded that more than 150 civilians were killed. Of them, five were Sinhalese and 145 were Tamils. But the government document Massacres of Civilians lists only the Mihinduwatte and Dehiwatte massacres in which five Home Guards were killed. Massacres of Tamils had been swept under the carpet by labeling them ‘terrorists.’

And Sinhala governments hoped to eliminate ‘Tamil terrorism’ by making every Tamil a suspect and by driving them away from their ancient villages!

Next: Chapter 45. Increasing Alienation

To be posted April 27

At this point Mr. Sabaratnam unexpectedly stopped writing his history of Pirapaharan’s time.