by T. Sabaratnam, February 25, 2004

Volume 1, Chapter 30

Original index of series

Shooting of Shankar

Rajani, who was on the verandah of the main house, saw the army jeep entering their compound. She ran through the house to the back door and shouted, “Nirmala Akka, army jeep is coming.”

She warned her elder sister because she knew an LTTE fighter, Shankar, was in her house. Shankar had gone to Nirmala’s house to convey the message Seelan had sent from Tamil Nadu that he had reached India safely. Seelan had also informed Shankar to convey his thanks to Nirmala, her husband Nithiyananthan and Rajani for treating and caring for him for nearly two weeks after he was injured.

Nirmala insisted that Shankar should have lunch. “Today I have cooked chicken. You must taste it and say whether it is tastier than your leader’s (Pirapaharan’s) preparation,” she said. Seelan had told her repeatedly that Pirapaharan’s chicken curry was “tops.” Nirmala served two pieces of chicken and Shankar was biting the first piece when Rajani shouted about the arrival of the army jeep.

Shankar slipped through the back door and ran towards the rear wall and the commando who ran to seal off the back entrance of Nirmala’s house fired at him. Shankar was hit in the stomach. Holding the bleeding stomach tightly Shankar ran nearly three kilometers to reach a safe-house where he handed his revolver to his comrades and collapsed due to excessive loss of blood, thus avoiding capture by the army and saving the weapon, both priority items in the LTTE’s code of conduct.

Shankar’s condition deteriorated fast and his senior colleague, Anton, whose real name was Sivakumar, undertook the perilous task of taking him to Tamil Nadu by boat. Anton took Shankar to Kodaikarai, one of the landing points of Tamil militants on the Tamil Nadu coast, kept him in a safe-house and arranged for a doctor to attend on him. Anton rushed to Madurai to arrange for his treatment, then he took Shankar to a private hospital in Madurai.

Doctors there declared that his condition was too serious.

Doctors there declared that his condition was too serious.

Pirapaharan, who was in one of the LTTE training camps, was informed. He returned immediately. Baby Subramaniam, who was at the hospital when Pirapaharan walked in, called the occasion poignant. Pirapaharan was highly emotional, he said. Pirapaharan, took Shankar’s hands into his, lifted them and pressed his cheeks on them. He put them back softly, went and sat near Shankar’s head and took it to his lap. Then he gently stroked Shankar’s hair. Shankar looked up. He seemed to have realized that his leader had arrived. He started muttering “Thamby. Thamby. Thamby…” Pirapaharan was “Thamby” (younger brother) to all, even to those younger to him. Shankar was six years younger.

Nedumaran was another who witnessed that moving scene. He has given a graphic description of that event in many interviews. In one interview he said, “They kept gazing at each other. It was impossible to guess what was going on in their minds. Pirapaharan kept looking at him intently, as if he was silently pleading with him not to go away.”

Pirapaharan was visibly shaken. He was seeing the death of one of his cadres for the first time. A 22-year old youth,

blossoming into manhood, was dying sacrificing his life for the sake of the honour and dignity of his nation. Tears rolled down Pirapaharan’s plump cheeks. The flame of life in Shankar gradually quenched.

Shankar, who was reading the Russian novel “One True Man’s Story” when he set out to Nirmala’s house at Nallur on that 20 November morning died after seven days of agony on 27 November, the day which has become a day of remembrance of valour and self-sacrifice for the cause of freedom of the Tamil Nation and the man, Shankar, became another “One True Man’s Story” of courage.

Shankar’s body was cremated in one of Madurai’s cemeteries. Pirapaharan wanted to attend it. Others prevailed on him and prevented him from doing so. Pirapaharan’s security was paramount, they argued. Baby Subramaniam, Ponnaman, Kittu and a few others attended. Nedumaran was one of them. That was a momentous day. The Sri Lankan Tamil freedom struggle had paid its first price with the life of an energetic youth.

Shankar’s death was not announced publicly. Pirapaharan felt the announcement of the death would encourage the army and the police to hunt the militants. The LTTE then was a tiny organization. It had not more than 30 cadres.

Announcement of Shankar’s death would demoralize the Tamil public and discourage youths from joining it. Shankar’s father was informed, however. His father, Selvachandran Master, told me that two “Tiger boys” had visited him one night and told him about his son’s death.

The LTTE announced Shankar’s death on his first death anniversary. Jaffna’s walls were plastered with his photograph.

Leaflets giving details about his life and exploits were distributed. Munasinghe told me that they knew about Shankar’s death a few months after it had occurred. The Defence Ministry, in its records, entered Shankar as the first Tamil militant to be killed by the army

Pirapaharan waited for seven years to proclaim the day Shankar died as Maveerar Nal (Hero’s Day). Pushed into the Vanni woods and surrounded by the Indian army, Pirapaharan needed more cadres and required a mode to motivate those who had stuck to him braving immense hardships and personal danger. Pirapaharan, well versed in classical Tamil literature and traditions, resurrected the well-treasured custom of honouring heroes fallen in battle and paying homage to them by erecting tombstones, the custom known as nadugal valipadu – nadugal means tombstone and valipadu worship or paying homage. Pirapaharan revived this tradition, well cherished in Tamil Sangam literature, as one of his motivation strategies.

The revival of nadugal valipadu has had the intended effect. It has transformed the attitude of the wives, children, parents and relatives of the fallen cadres from the feeling of deprivation and wailing to that of participation and pride. It brought the families of the dead fighters closer to the LTTE rather than estranging them from it. It gradually restored the martial culture of the ancient Tamil society. The uppermost aspect of this culture surfaced in the eastern province in the year 2000, when LTTE propaganda reminded the tradition of mothers sending their sons to battle, anointing their foreheads with sandalwood paste, veera thilagam, to replace their killed husbands. And many mothers were roused to do it.

Sinhalese and non-Dravidian Indian policy planers and commentators fail to understand and appreciate the roots of the martial culture of Tamil Dravidians. The spread of Aryan Hinduism and culture blunted the militaristic character of ancient Tamil society. Pirapaharan had gone to Dravidians’ roots and brought out their inborn militaristic talents.

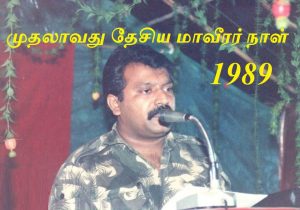

In 1989, Pirapaharan declared 27 November, the day Shankar died, as Maveerar Nal (Hero’s Day) and six hundred LTTE cadres, men and women, dressed in battle dress, assembled at a secret location in the Nithikaikulam jungle in the Mullaitivu district to pay homage to the 1307 martyrs who had till then laid down their lives for the cause of liberating the Tamil people. Photographs of those who had fallen were placed on a pedestal, flowers were sprinkled at their foot and

In 1989, Pirapaharan declared 27 November, the day Shankar died, as Maveerar Nal (Hero’s Day) and six hundred LTTE cadres, men and women, dressed in battle dress, assembled at a secret location in the Nithikaikulam jungle in the Mullaitivu district to pay homage to the 1307 martyrs who had till then laid down their lives for the cause of liberating the Tamil people. Photographs of those who had fallen were placed on a pedestal, flowers were sprinkled at their foot and

coconut oil lamps were lit following the lighting of the main lamp by Pirapaharan. The ceremony, called Eekai Sudar Ettal,

was the simple beginning of what has now grown into an elaborate ritual. Pirapaharan was moved by what he had initiated and, in that emotion-charged atmosphere, he delivered his first Maveerar Nal address extemporaneously.

In that brief address, meant to explain the reasons for originating the ceremony, Pirapaharan said: “Today is an important day in our struggle. Today we have started the Hero’s Day in order to pay homage to the 1307 fighters who had sacrificed their lives to attain our sacred objective of Tamil Eelam. We have started this for the first time. You know that many countries in the world honour their freedom fighters by remembering them. We too have decided to proclaim a day of remembrance. We have done so today, the death anniversary of the first hero who attained martyrdom.

“Our people are used to remembering only those who held high posts and who lived comfortable lives. We have decided that leaders should not be given a special treatment. We consider all combatants who sacrificed their lives in this sacred struggle equal. By remembering all those who sacrificed their lives for the struggle on the same day, we will be able to give the credit for the achievements of the struggle to every combatant. Otherwise, with the passage of time, the credit would be given to only a few persons and the sacrifice of others would be neglected and ignored. Any nation that fails to honour heroes, wise men and wise women would be a nation of barbarians. Our nation, more than the others, gives great respect to women. But it has not given similar respect to heroes. Today we have initiated a change. We have begun to give respect to our heroes.

“Till now, we failed to pay respect to the heroes. Today we have changed that. Today, we have allocated a day to pay homage to them. If our nation is able to keep its head high in the world, it is because 1307 heroes sacrificed their lives. It is because they fought without thinking of their lives we have won the respect of the world. Let us from today, observe the Maveerar Nal as an important day every year in our lives.”

That extemporaneous speech gave rise to the tradition of Maveerar Nal Perurai which means Hero’s Day Address. The annual address assumed importance and significance over the years, especially in the past few years; it has acquired immense political import. The celebrations, too, expanded from 1990 when, with the departure of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) and the start of the Second Eelam War, Jaffna peninsula fell into the hands of the Tigers. From that year to 1994, the observances were held for a week, while from 1995, when LTTE lost the control of the peninsula, they was restricted to three days.

Maveerar Thuyilum Illamgal

Activities connected with the Maveerar ceremonies commence at the beginning of November. Literary, cultural and sports competitions are held at village and district levels. Families of heroes, known as Maveerar kudumbamgal are given important places in these activities. The graveyards known as Maveerar thuyilum Illamgal (Houses where heroes are in eternal sleep) are cleaned and painted and readied for the final day ceremony. In a main location, Pirapaharan would take part and in others, area leaders conduct the rituals. Members of the maveerar kudumbamgal would stand in a line with flower trays and small earthen coconut oil lamps or candles depending on whether they are Hindus or Christians. The torch to light the main Flame of Sacrifice, the thiyaga sudar, is brought by LTTE cadres in a relay and handed over to Pirapaharan at the main location or to area leaders at other places. The Flame of Sacrifice is to be lit at 6.04 p.m., the time Shankar died. Then family members light lamps or candles they carried and place them at the foot of the graves of their dead relative. Pirapaharan delivers his annual address before the final lighting ceremony.

Arrest of the Nithiyananthans

Commandos chased Shankar, who ran holding his injured stomach tight, but could not keep pace with him. Shankar knew the area very well. He knew the lanes and by-lanes. After the commandos returned from their unsuccessful pursuit, Munasinghe and the officer who went with him entered Nirmala’s house.

Munasinghe told me that Nirmala was angry. She started screaming at him. “How dare you enter my house. Do you have a search warrant?” she demanded. Even when told they don’t need a search warrant under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, Nirmala continued shouting: You have no business to search my house. I will report you to the President.”

“We searched the house despite her yelling,” Munasinghe said. “We could not find anything other than a few bandages and a pair of crutches.”

“Why are you having this?” Munasinghe asked pointing to the crutches.

Nirmala answered: “That’s for our drama practice.”

Police officers who arrived a little later also could not find anything. Then they turned over mattress on the double bed.

There was a big patch of bloodstain.

“What is this?” Munasinghe asked.

“I was bleeding last week.”

“If you bled so much you would not be alive today.”

Nirmala and her husband Nithiyananthan were arrested and taken to Gurunagar for further investigation.

Militants and others who were taken to Gurunagar Army Camp for investigation call it a torture chamber. Munasinghe, in his book, says the Nithiananthans were tight-lipped at the start but started talking later. They started talking, militants alleged, after they were severely assaulted and tortured.

The story of the CEL

Efforts to bring the militant movements together were on while the LTTE stepped up its attacks in Jaffna. The efforts, which initially concentrated on preventing Pirapaharan and Uma Maheswaran fighting each other – the efforts of Perum Chitranar and Amirthalingam – were given a wider focus around August 1982 by Arular.

A.R. Arudpragasam

I asked Arular (A.R. Arudpragasam), whose book “Traditional Homelands of the Tamils” which I helped to edit and whose forthcoming publication “Monetary Exploitation” I helped to proofread, what prompted his effort. “Hunger,” he said and laughed. He said that was the primary reason. “We were all short of cash. There were days we slept with empty stomachs.

It was on one such night I thought of uniting the militant groups so that we could get at least a small share of the booty Uma had brought with him,” he said. He was referring to the 20 packets of gold Uma had taken with him when he crossed over to Tamil Nadu on 25 February.

“Did Uma give any money to other militant organizations?” I asked Arular.

“No,” he said. “Whenever I mentioned the matter he brushed it aside,” he added.

But Arular had no regrets about his unity move. Arular, who had been living in Tamil Nadu following the murder of Bastiampillai and the search of the Kannady Farm in 1978, had known the need for unity among militant groups.

“Why can’t you people unite?” was the question repeatedly asked from him by Sri Lankan Tamil expatriates and the supporters of the Eelam struggle in Tamil Nadu. Arular had no proper answer.

Chelvanayagam at 1956 Galle Face satyagraha

Arular, born in Naranthanai, Kayts in 1949, developed interest in politics, very early. His father, J. Arulappu, a teacher and a supporter of the Federal Party, took part in the 1956 Galle Face satiyagraha. Arulappu returned home with a broken arm, which Arular calls “the prize Sinhala thugs gave him for sitting cross-legged and praying to Gods that his language be given its rightful place.” His father migrated to Vanni in 1964 and established a farm in the village Kannady following a Federal Party decision to protect the border villages from Sinhala encroachment.

Arular was at Trichi airport to catch the flight to Palaly in Jaffna, while returning from Lebanon where he had taken the

second batch for training, when he received a message that he would be arrested when he landed in Palaly. “I was told Kannady Farm had been raided. Then I went to Chennai,” he said. He had been arrested two weeks earlier at Beirut airport when he began his return trip. Arular, who received training in explosive devices, tried to bring some explosives home hidden in his suitcase. Custom officers who detected them detained him. Al Fatah men, who were very influential in Lebanon, got Arular out saying that he was an engineer and was taking the explosives for his experiment.

“It was a difficult task,” Arular who launched an effort to bring the militant groups together said. By mid- 1982 the number of Tamil militant groups had proliferated to five: LTTE, PLOTE, TELO, EPRLF and EROS. There were personal rivalries among the leaders, though not as intense as the conflict between Pirapaharan and Uma. EPRLF’s K. Padmanaba had differences with Uma. Intrigues and undercutting among militant leaders and their cadres were common.

Those differences were encouraged and to some extent promoted by Tamil Nadu politicians. The LTTE was aligned with Nedumaran’s Kamaraj Congress and K. Veeramani’s Diravida Kazhagam. Sri Sabaratnam pulled TELO towards M. Karunanithi’s Diravida Munnetta Kazhagam. PLOTE was aligned with Perum Chitranar’s Thani Thamil Iyakam and the Communist Party of India (Moscow Wing), and EPRLF had established links with the Communist Party of India (China Wing.

EROS was the only group that tried to keep away from aligning itself with any group or party in Tamil Nadu.

In political philosophy the militant groups also differed. Though all professed Marxism and socialism, they differed in the intensity of their commitment to that ideal. The LTTE’s commitment to Marxism was peripheral. Its commitment was confined to eradication of the caste system, abolition of the dowry system and other forms of social evils. EPRLF, on the other hand, was fundamentally Marxist and was concentrating on mobilizing the various sections of the people: women, youth, students, workers, peasants and fishermen.

“When I analyzed the problem I realized its immensity,” Arular said. “We had to work out a unified structure while

maintaining the individuality of the different organizations. The PLO model looked handy,” he said.

He prepared a scheme similar to that of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and named it the Committee for Eelam Liberation (CEL). It would have an apex body comprising the heads of five committees. Each committee would be headed by the leader of one of the five constituent groups.

“I found to my amazement that my plan was acceptable to all of them,” Arular said.

The militant leaders were amenable to Arular’s scheme because they were under pressure from intellectuals, prominent persons and sympathizers in Sri Lanka and India to unify their resistance to Jayewardene government’s ‘oppression.’

Pirapaharan of the LTTE agreed to serve as the chairman of the Military Affairs Committee, Uma Maheswaran of PLOTE as the chairman of the Political Affairs Committee, Balakumar’s EROS as the chairman of the Economic Affairs Committee, Sri Sabaratnam of TELO as chairman of the External Relations Committee and Padmanabha of EPRLF as the chairman of the Internal Security Affairs Committee.

Arular recalls that the first decision taken by CEL was to marginalize the TULF which was cooperating with Jayewardene.

“We would have done that by fielding an independent group to contest the parliamentary election scheduled for mid-1983.

Jayewardene, by holding the referendum, made it impossible for the CEL to do that,” Arular said.

The second decision of the CEL was to induce the Jayewardene government to talk to it instead of the TULF. The CEL issued a statement in March 1983 which called upon the government to commence “a positive dialogue” with the militants to work out a solution to the Tamil problem and requested it to place a proposal “which would be a viable alternative to Eelam” for their consideration. Arular said this was done as a continuation of their strategy of marginalizing the TULF.

Jayewardene and Amirthalingam ignored the statement, Jayewardene because he had re-established better relations with Amirthalingam and Amirthalingam because he misjudged the mood of the Tamil people and that of the militants.

Mass Agitational Phase

The arrests of Fr. Singarayar on 14 November, Fr. Sinnarajah on 15 November, both Roman Catholic priests, Rev.

Jayathilakarajah, a Methodist priest, on 18 November, Rev. Donald Kanagaratnam, and Anglican priest, on 15 December, and the arrest of Nithiyananthan and his wife Nirmala, university lecturers, on 20 November, generated a new phase – a mass agitational phase – in the Tamil struggle. The peculiarity of this phase was its spontaneity.

Thousands of priests, nuns, laity and students demonstrated inside and opposite the churches. They picketed government buildings and held satyagraha. “The Broken Palmyra” provides a detailed account of this new phase. The book quotes extensively from Saturday Review, a weekly published in Jaffna. The Colombo publications, especially the Lake House group of papers, which printed defence ministry plants, without any verification, had no inkling about this new far-reaching development.

Their concern was confined to protecting the interest of the Sinhalese, which they identified with the interest of Sri Lanka.

Saturday Review, on 20 November 1982, in its lead story titled STOP THIS PEN AND DAGGER JOURNALISM strongly protested against the Colombo press’ unprofessional practice of printing slanderous allegations with impunity. These stories, published on the orders from the very ‘top,’ justified the arrests of the priests and others by simply dubbing them terrorists. The story about the arrests of priests was headlined, ‘Terrorist Priests Arrested.’ The press had thus arrogated to itself judicial power and pronounced the arrested priests terrorists.

When Rev. Kanagaratnam was released shortly afterwards, the Lake House Sinhala daily ignored the story, while the Daily News and Thinaharan pushed it inside. Rev. Kanagaratnam, when he was the principal of the Pilimatalawa Theosophical Seminary, refused to hoist the national flag on independence day in 1978 saying that the Tamil region of Sri Lanka had suffered serious oppression during the 1977 riots. Some Sinhalese members made an issue of that and Rev. Kanagaratnam resigned from the seminary and founded the Unity House in the border area of the Vavuniya district to work for Sinhala-Tamil amity. He was arrested on the ground that he was promoting Tamil terrorism, but released when it was found he had good personal relations with the Sinhalese people of the area.

The episodic protest fasts and demonstrations drew the entire Tamil population into a struggle against the government.

They mobilized and motivated the people to a high degree. The police and the army, through their arrests and the

mishandling of the protests, the outcome of the Jayewardene government’s short-sightedness, set in motion a process which sucked in even the unwilling TULF. As the protests grew, a collective one-day fast took place on 30 November in the northern and eastern provinces and the TULF, to avoid being left out, to quote Saturday Review, “mounted the chorus of protests.”

The Jayewardene government and its police and army chiefs failed to realize the seriousness of the fresh environment.

St. Anthony’s Church, Vavuniya 2019

They, through their revengeful actions, fuelled the fury of the Tamil people. On 15 December, steel-helmeted police used batons and tear gas inside St. Anthony’s Church at Rambaikulam in Vavuniya.

Saturday Review of 18 November reported the St. Anthony’s Church incident thus:

“Hundreds of girls, women, children and men including Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus and Christians, began a protest fast on Wednesday (15 December) on the Church premises. As scheduled, a silent march headed by school girls with mouths gagged and wearing black badges had just come to the road when police pounced upon them, dragged the girls by their hair, and kicked and baton- charged them when they defied police orders to disperse. The baton charge took place when the girls sat on the ground refusing to move. The police stormed into the church and baton charged protesters who sought refuge there.”

The government’s handling of the protests through police repression only helped to mobilize, radicalize and unify the people. They joined hands, irrespective of sex, age, caste, creed, social and educational differences to oppose state repression and the law, The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), that empowered the police to search premises and arrest persons without warrant. University and school students who started leading the protest focused their opposition on the PTA.

Jaffna University and school students conducted a massive demonstration on 26 January 1983. They marched through the streets of Jaffna demanding the repeal of the PTA and the release of student leaders, clergy and social workers. They followed the march with a 4-day satyagraha commencing on 1 February. The Northern and Eastern Provinces were crippled on the final day of the satyagraha, 4 February, Sri Lanka’s independence day.

Pirapaharan, an astute political observer, followed these developments minutely, and decided that Jayewardene had created for him the environment conducive for the takeover of the leadership from the TULF. He also decided that he should not give Uma Maheswaran an opportunity to fill the leadership vacuum. He discussed these developments intensively with his trusted colleagues, Baby Subramanian and Seelan, who had recovered from his knee injury. He also discussed these developments with his mentor, Nedumaran. With Nedumaran’s blessing, Pirapaharan crossed over to Jaffna in the early hours of 18 February 1983 with Seelan. And on that very evening the LTTE made its first strike by killing the despised Point Pedro Police Inspector E. K. R. Wijewardene, thus announcing its return.

Next: Chapter 32, The Return of Pirapaharan

To be posted on March 3