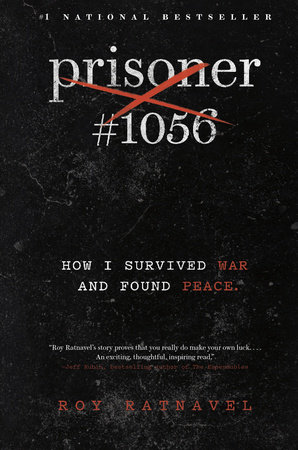

ABOUT PRISONER #1056

An incredible immigrant story from a prominent Canadian Tamil who fled torture and imprisonment, arrived in Canada with $50 in his pocket, then rose from the mailroom to the executive suite of the country’s largest independent asset management company.

Roy Ratnavel’s astonishing journey began at age seventeen, when he was seized by government soldiers and interned in a notorious prison camp for no reason other than being born a Tamil. He saw friends die, and was tortured for a few months—until an unlikely encounter allowed him to send a message beyond the prison walls, which led to his release.

Seeing nothing but more danger in his son’s future, Ratnavel’s father sought refuge for his son in Canada, far from the ethnic violence that was consuming Sri Lanka. When the consular immigration officer asked for proof that the boy’s life was at risk in his homeland, Ratnavel simply lifted his shirt to show the man his unhealed scars. It wasn’t long before he was on a plane. His father was shot and killed three days later.

PRODUCT DETAILS

Available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHORPRAISE

“Millions of people fleeing countries less fortunate have found here in Canada a refuge from mistrust and hatred and violence which has allowed them to achieve their potential in the rich soil of our freedom. Roy’s life is one such story. While Roy’s remarkable personal journey is unique to him, reading his book one cannot help but hear a familiar refrain that will resonate with millions of Canadians, because at its core it is the story of the immigrant experience. And in the final analysis, we are all children of immigrants.”

—The Right Honourable Brian Mulroney, 18th Prime Minister of Canada

“Pick up this book and you’ll feel like taking on the world. Roy Ratnavel’s story proves that you really do make your own luck, that you really can make it to the top with hard work—and that there are still people out there with the courage to speak their minds. An exciting, thoughtful, inspiring read.”

—Jeff Rubin, bestselling author of The Expendables

“A stirring struggle to forge promise and purpose from a life scarred by pain, and to bridge two worlds with compassion and hustle learned in each of them. Ratnavel shows we can pull each other up by our bootstraps.”

—James Bradshaw, reporter for The Globe and Mail

by Bass Sinnathamby on GoodReads, April 20, 2023

Roy’s book is a compelling and emotional read that sheds light on his personal experiences of prison torture, the loss of his father, and his mother’s mental illness. His raw and vulnerable storytelling showcases his unwavering determination to overcome every obstacle. The book provides a unique perspective on the human cost of conflict and displacement, contextualizing Roy’s struggles against the backdrop of his country’s civil war and the suffering of the Tamil community. Overall, this thought-provoking and nuanced portrayal of a remarkable life journey is a must-read for anyone interested in the complexities of the human experience and the resilience of the human spirit.

In one of the chapters of his book “Prisoner #1056,” set for release on April 18, Roy ponders, “Was my fate my own to create, or was it predetermined?” A question that each one of us has pondered from time to time. He defines the answer at the end of the paragraph itself. “What we believe is our fate.” In subsequent pages, he elaborates, “Fate is not what happens to you. It’s how you allow what happens to you to shape you.” This very much is the essence of the book and the wisdom that Roy aims to instill in his reader.

In “Prisoner #1056,” Roy recounts his hero’s journey. He not only takes us through the dingy floors of a Sri Lankan prison where he lies stripped of dignity, identity, and void of strength to even think if he might survive the day that’s to come. He also takes us through the dark corners of his inner self; the anger, the trauma, and the demons that he constantly battles. Battles that, at times, challenge him to simply look in the mirror and accept the person that looks back. This courage to bare oneself on the pages of this book, being unapologetically proud in celebrating his success while also being self-critical, vulnerable, and rediscovering himself at every challenge that life throws at him is what makes this memoir heartfelt, sincere, and profound.

Interlaced within is a love letter to dear Appā, an ode to Canada, a celebration of his Tamil identity, and gratitude towards every life that shaped him into becoming who he is today. A Tamil story to the world, Roy Ratnavel through the pages of “Prisoner #1056” dares us to take destiny into our own hands and create the life, meaning, and legacy that we want the future to uphold and celebrate.

“Prisoner #1056” is available at: Amazon & Indigo (Canada)

TC’s Interview with Roy Ratnavel on Prisoner #1056:

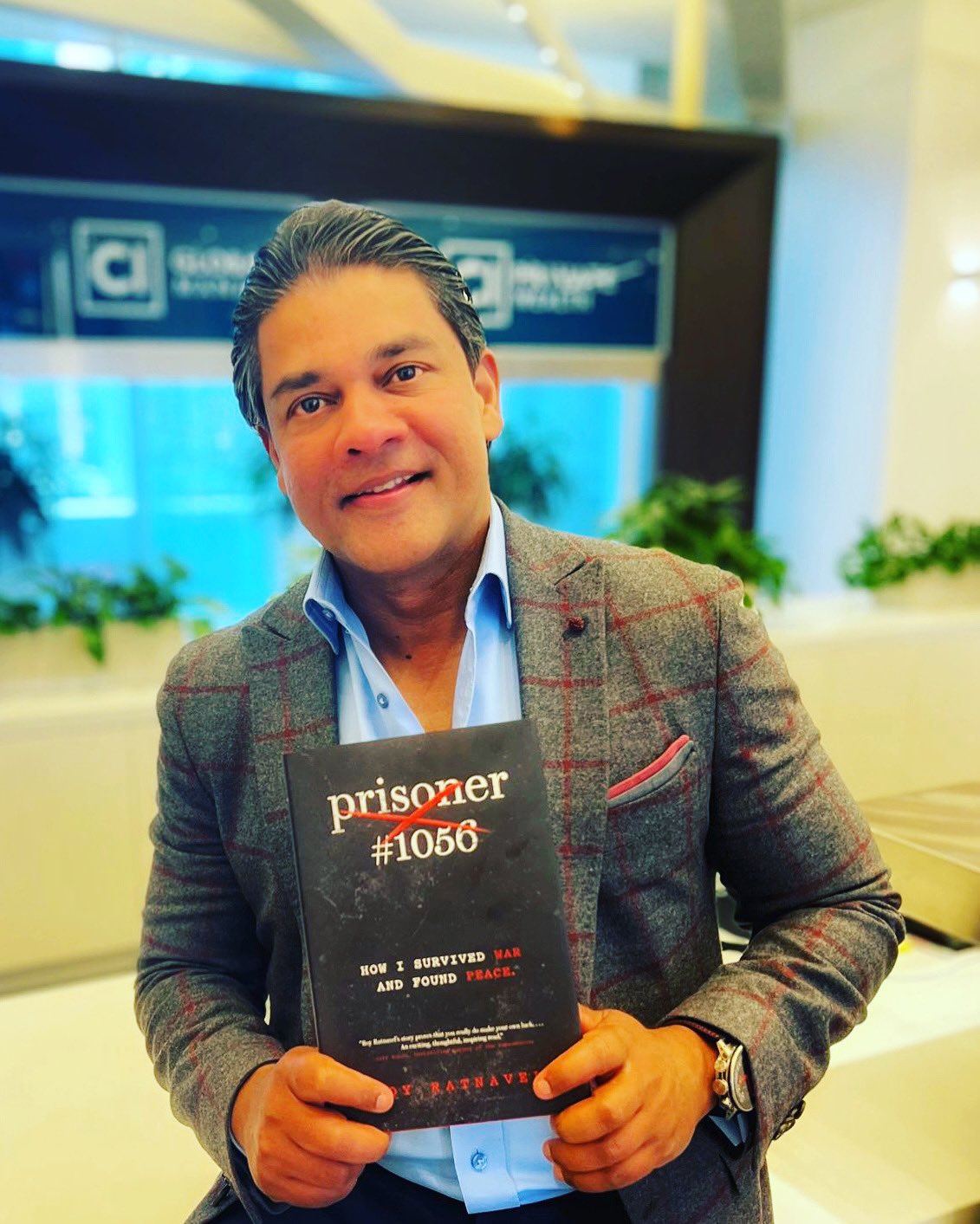

Roy with the author’s copy of Prisoner #1056.

“Prisoner #1056.” Why did you choose to name your book by a token that represented one of the lowest points in your life?

It was intentional because for every human being self-identity is important. So what happened here was that they stripped away that from me and many others like me in prison and just gave us a number. So we were known as the prisoners, as this group, where I was just this number. It also ties in with the end of the book too where I argue for individuality rather than group identity. My intention here, rightfully or wrongfully, was to show the evolution of this character, which is me, going from an utterly hopeless dark moment into somewhat of a fulfilled life. Crafting my own identity in the process. I wanted to take the reader through that journey. Also, it was catchy. And when you say “Prisoner #1056,” it creates curiosity. I wanted to make it more mysterious. On the cover, you will notice the two red lines, which are indicative that I am no longer Prisoner #1056.

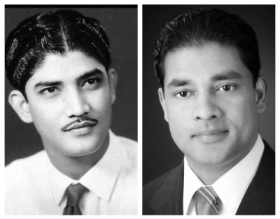

I understand that this is deeply personal. Why was it easier for you to come to terms with ‘Prisoner #1056’ compared to owning your birth name, ‘Subendran’? It was also interesting to me that you owned your name, ‘Subendran’, in the final chapter.

It was a difficult decision to make to bury my past. And I thought that getting rid of the name and re-branding myself, maybe at some psychological level, created a new me. But then I realized, towards the end of the book, that I became more comfortable with who I was from the beginning. I was always running away from the past. Whereas today, I am in a position where I am comfortable about everything. Reflecting on it, I am still the same kid just in an older body. Those past lessons are unchangeable. They can give you a path to a new life and better success.

Also on some level I was ashamed to be identified as a Tamil at that point in my life. Hence why today I go out of the way to mention that I am unapologetically Tamil by heritage. And I want it to be on record for saying that.

I also use Viktor Frankl’s quote in the book, which is, ‘The greatest human need is meaning,’ and without it, you are lost. And I don’t think I had meaning in my life before. I would like to say that I have found meaning, at least in my own way, and that’s why I am back to using Subendran more often, as you can see in the later chapters.

There is a key moment in the book where your six-year-old son, Aaron, whom you had assumed to not know about your time in prison, suddenly asks “Were you sad when you were in prison, Daddy?” While your answer was brief yet honest then, have you shared this experience with your son? And if so what was his reaction?

Yes. He doesn’t particularly remember that conversation. But I have been honest with him about what happened to my father as that was one of his questions a long time ago for which I answered that he died in an accident. I didn’t want to give him nightmares. But now he knows what happened.

And in the context of his life today, now he’s eighteen and I was eighteen when I came here so it’s such a dichotomy. A dichotomy in the sense that the life he has is far different and better. Not to say that he doesn’t have challenges. They are different. It would be unfair for me to compare my challenges to his. As he said to me one day “Dad it’s not my fault that I was born in a free country. So you can’t be holding your past to shape mine.” But I would take lessons from it and have conversations. Resilience, fighting back, being proud of who you are, having individual thoughts, questioning things and evolving your mind. But I wouldn’t say that he has read the book yet but he has promised to do so.

When you visited the place where your father was killed you weren’t able to display any emotions. But the morning after your son’s birth you completely break down in front of the mirror. What was about the birth of Aaron that brought about those emotions?

I didn’t want to elaborate too much on it in the book. I wanted the reader to have their own thoughts about what would have been the emotions I went through. There are a couple of layers to it.

Now that I am a father I realized how I needed to make my precious little baby be safe, grow old and be successful. When my father died it was just two days after I came to Canada. He had no idea if I would succeed or fail. He had his own anxieties about me coming to Canada by myself at the age of eighteen. So, it was just that as a father I felt what he would have felt when I left Sri Lanka, when I was in prison or when he was shot and took his last breath. The feeling that he won’t be able to guide me anymore.

It was all of this plus the fact that I had not shown any emotion, when my father died or when I visited the place where he was shot. I had become this person thinking that if I cried then my tormentors would win. It may have been a mistaken line of thinking. In fact I should have let it out, dealt with it. And in that way I wouldn’t have had all these anger issues that eventually became a bit of a roadblock to my success. So in that very moment, by myself, in front of the mirror, after the tsunami happened, I was catching myself in the mirror and just blew up. All that burden just came out.

Captain Udugama, who unjustifiably arrests you, gets killed and his funeral, ironically, happens the day you are rescued by Uncle Fernando and released from prison. Appa gets killed by the Indian Army and subsequently Rajiv Gandhi, who was in charge of the Indian Army at that time, gets killed by the LTTE. Do these events help with your healing process knowing that there is some level of closure to those dark moments?

No. The crux of it isn’t about revenge. If it was just about revenge then that would be it, correct? You would say my dad died at the hands of the IPKF, Rajiv Gandhi was in charge of that, so the score is settled. But there was nothing about my life, at that time, that was settled. I didn’t have my father, I was a mess, and my mother was battling with mental illness because of that. Ultimately I realized that revenge was not the solution to whatever “victimhood” I was feeling at that time. The solution was going back to what my Dad said. “I don’t want you to survive, I want you to live.” Then understanding that it’s such a lowest common denominator thinking to say “avenge someone’s death.” The best way to avenge is to live better. To fulfill the very reason that my father sent me down here.

Let’s think about Uncle Fernando. He had his own reasons to avenge his son’s death. I am sure he has done bad things as a Colonel. But he didn’t look at me as an enemy. He looked at me as a friend’s son. There is some beauty in that too, in humanity. Sometimes if you break down the barriers to see someone as purely human and then that feeling can unite people beyond race and religion and other markers. And I think that is the theme that is running through the book in a way.

For people who go through such cathartic experiences as you have, faith or spirituality usually finds a place as a means in making sense of it all. But this seemed notably absent. Is there a reason for it?

My father, for my inspiration and or deficiencies, right or wrong, has been a source of my strength. My grandfather was a religious man and a devout Hindu. He didn’t drink or smoke. My father was the opposite. He drank a lot, smoked a lot and scoffed at all religions. So growing up under his guidance, I had resentment towards god, religion and faith. Remember my dad mentions: “Vidhiyaiyum mathiyāl veḷḷāḷam”—Even fate can be overcome by the mind. Ironically he couldn’t change his fate.

I am not an atheist nor a religious person. I figured that if I did the right things, the outcome will be something that is desirable. For me these were hard work, learning, and progressing. The lesson in that is that it comes at a cost. The cost of relationships, friendship, and just generally as a person, the cost of you, you are hollowed out.

I talk about the incident where I found myself upside down in a car. Then, I got into a truck and looked at myself in the mirror, wondering, “What is this all about?” I believe I had a potentially “spiritual moment,” if I may say so. I could have died at that moment, but then what would be my legacy? What is life all about? Just running around, making money, and then one day you die, and is that it? It was a pivotal moment for me. Even though I had wanted to be like Bill, traveling to nice places and making money, that almost fatal moment made me reflect on my family. That’s why I mentioned that when I went back and slept that night, it felt right.

Read part 2 of our interview with Roy Ratnavel here.

Bill Holland, one of the most extraordinary persons in your career, knowingly or unknowingly created valuable teachable moments. There is a moment where your anger takes the better of you when Bill mentions “you have outgrown the company. Quit or I’ll fire you”. You quit CI, to be rehired by Bill 2 years later. What did you learn about yourself in these 2 years and would you consider this to be the most valuable lesson that Bill taught you?

Yes. I would say that one of the lessons I learned was that arrogance is one of the key ingredients in failure. My whole idea was to be successful at any cost. I wanted to get to a point, get there fast, trample anyone in the way and get there. It was a tunnel vision. Bill kicking my butt to the curb, humbled me. And it also taught me that even though Bill was my mentor and friend, that people make business decisions which may look heartless at that point but ultimately it’s business.

Bill was running a business and I was becoming an impediment to that mission. I remember the Navy Seals saying that “It’s not about the man but the mission”. I wasn’t about the mission. I was all about myself and my arrogance. Him kicking me out, really humbled me and made me re-brand myself.

The second time around, I was open to new ideas, I was open to listening to other people. Even then I got into my arrogance again. I was trying to assert that “I am here, I have arrived”. All of these things stem from me not having meaning in life and thinking if I become rich then that’s it. That is a very shallow way of looking at life. That’s my biggest failure. It was humiliating and humbling. That is what I learned.

Bill Holland, as Roy’ describes as his mentor, cheerleader, disciplinarian and friend, holding the copy of Prisoner #1056

There is a specific commentary in your book on what it means to be Tamil. We don’t have a land to call our home and as a language it has no association to a specific religion. This makes the language the root of its identity. Do you think Tamils, be it from native lands or the diaspora, give enough emphasis on learning the language which is crucial for this identity to survive in the future?

In an ideal world, we want our kids to be able to speak the language. We don’t exist in the ideal world. I am a pragmatic human being. By saying this, I would love to see every Tamil kid speak Tamil.

To give you an example. I lived in Vancouver for 20 years and Aaron was born there. He had no facility to mingle with other Tamils via community events in a place like that. I bear responsibility for this. I could have done better. I was traveling and Sue was busy with her work and had challenges about her own ability to speak the language as a Tamil girl. So somehow this ball got dropped. I am not saying this to justify my son’s lack of ability to speak Tamil.

Observing what our people do to little kids when they speak Tamil. Which is that every time a kid tries to speak Tamil with a bit of a kochcha Tamil, they make fun of it. I don’t think that really lends to getting Tamils to speak the language. That’s one argument I make.

The other is, I have seen, when I went back to Vanni in 2002, South African Tamils who visited, who didn’t speak Tamil at all, but came there because they felt this is something. To your point about a land that they can connect to.

I have dealt with a lot of Jewish people throughout my life. And there are many kids who don’t speak the language, Hebrew, or don’t practice the religion. But they have this strong sense of Jewish identity within themselves. With the absence of land, we should talk about the feeling of who we are as Tamils, stemming from an ancient culture.

The last point I would like to make is, during the Tamil revolution struggle, I have met many Tamil scholars, pandithars, who worked against the Tamil cause. So would you rather take someone who is an expert in Tamil language but fought against the land, or, would you take someone like the South African family I met, who couldn’t speak a single word of Tamil but felt strongly about their Tamil identity and wanted to do something? So in that sense I am very pragmatic and take the latter rather than the former. Ideally, I would take someone who can speak really well and be proud of being a Tamil.

Canada, unlike many countries in Europe, celebrates hyphenated identities i.e. Tamil – Canadian. In finding comfort and familiarity on one side of the equation are we alienating the other?

It is great that as Canadians we can celebrate our own cultures. But the issue is “What is a Canadian?”. Do we know about or appreciate other cultures? I have seen the third generation of Tamil kids, who tend to live in an enclave of their own, mostly within people of color, and that’s it. They become very insular. I think there is a risk in that. Luckily I was in a unique position to visit many small towns in Western Canada where I was able to see the commonality in humanity. Basic human feelings and challenges are universal. So this is why I have hope for humanity. If we focus on that universality and less on our differences (race, sexual orientation, religious background etc.). The lack of assimilation is not a bad thing, but assimilation is a good thing.

I was living in Vancouver during the 2010 Winter Olympics and I attended the quarterfinals hockey game between Canada and Russia. That day gave me the definition of Canada. There were people who never played hockey in their lives, people from all demographics, waving red and white flags, cheering for the Canadian team. That’s when I realized what Canada was all about. If we can have cross-cultural assimilation that would be great. It’s an ideal world.

“There are no winners in war, only survivors. I’m one of many…..I have been living in two worlds. One with loss, grief, and endless misery. And the other with peace, prosperity, and profit….I often struggled to reconcile the two…” Have you been able to reconcile these two worlds as a result of writing this book?

Yes. I am not sure if I can say 100% yet. But writing this book really helped in starting to reconcile that, finally, where two different Roys (or Subendrans) merge into one. And telling this story publicly will make it more so to be proud of who I am, where I come from and what individually and collectively I was able to achieve. This story, our story collectively, is going to be told and heard.

I think I will always live in two worlds, but I won’t be dwelling on it. In a way we have to live in two worlds. You have to think about friends and family you left behind and you still have to live a life here. It’s always going to be there no matter what. But you find a better way to deal with or at least see the progression of it.

This book is ultimately a thank you gift to Appa. There is no doubt that he would be proud of what you have achieved and it’s probably beyond what he had dreamt for you. But is there something that you still feel where Appa would go “I wish you did this, or didn’t do this”?

I wish that I had more of my father’s diplomatic ways in dealing with tough situations. I think I took the hard path to where I am today. I am always good at managing down, or up, but never good at managing sideways. Ultimately my colleagues had reasons to grind with me. So when it came to promotions or better opportunities, it was always a struggle. Even if you change yourself or repent for your mistakes, people never forget. I am much calmer, more thoughtful and a better person in many other aspects but people always remember the Roy from 20 years ago.

If you had to go back to the moment where either Roy is in prison or Roy is at the airport leaving Sri Lanka, what would Roy of today tell him?

I would say that, in life, as my father said, you don’t get to choose what kind of world you will live in, you only have the choice of reacting to the environment. And I think that lesson is clearer to me now. Because all I was thinking at that time was uncertainty. I don’t think that could happen at the age of eighteen. You are immature and would not have the deep thoughts to figure out how to maneuver certain things. But in hindsight now, if I had to redo it, I would have worried less. But then worrying less also has its own implications. You then think you don’t need to try anything and somehow you will land in a good place. That’s hope and sometimes it’s not a good strategy either. It’s a tough question to answer, but that’s what I would say.

This is a truly exceptional post offers a detailed and insightful glimpse into the content of the book in question. The publisher has masterfully crafted their words to provide both glares and glimpses of the book, skillfully highlighting the most captivating aspects of its content.

While the article is certainly on the longer side, it is impeccably executed and serves to fully capture the essence of the book, leaving the reader with a deep and comprehensive understanding of what to expect from its pages.

Well done!