by Niran Anketell, ‘Groundviews,’ Colombo, April 20, 2016

On a recent visit to the United States, Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera made a revealing series of comments in response to a question at a forum organized by the United States Institute of Peace. When asked about the government’s timeline to introduce what the government calls “reconciliation mechanisms”, his response reflected his view that controversial Transitional Justice (TJ) mechanisms must be initiated quickly, without much delay. Citing Margaret Thatcher, he claimed that the most controversial aspects of a government’s agenda must be implemented within “a year or two” of its assumption of office. He said the government had “set itself a target of one year” to establish the mechanisms, and this was why the consultation process was supposed to take place within “three months”. He also revealed that he believed some mechanisms could be established even before the consultation process was concluded.

Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera gestures as he speaks at a media briefing in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Sept. 17, 2015. Samaraweera said Sri Lanka will begin talks next month on creating a special court to examine alleged atrocities during the country’s civil war, in which tens of thousands of people died. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

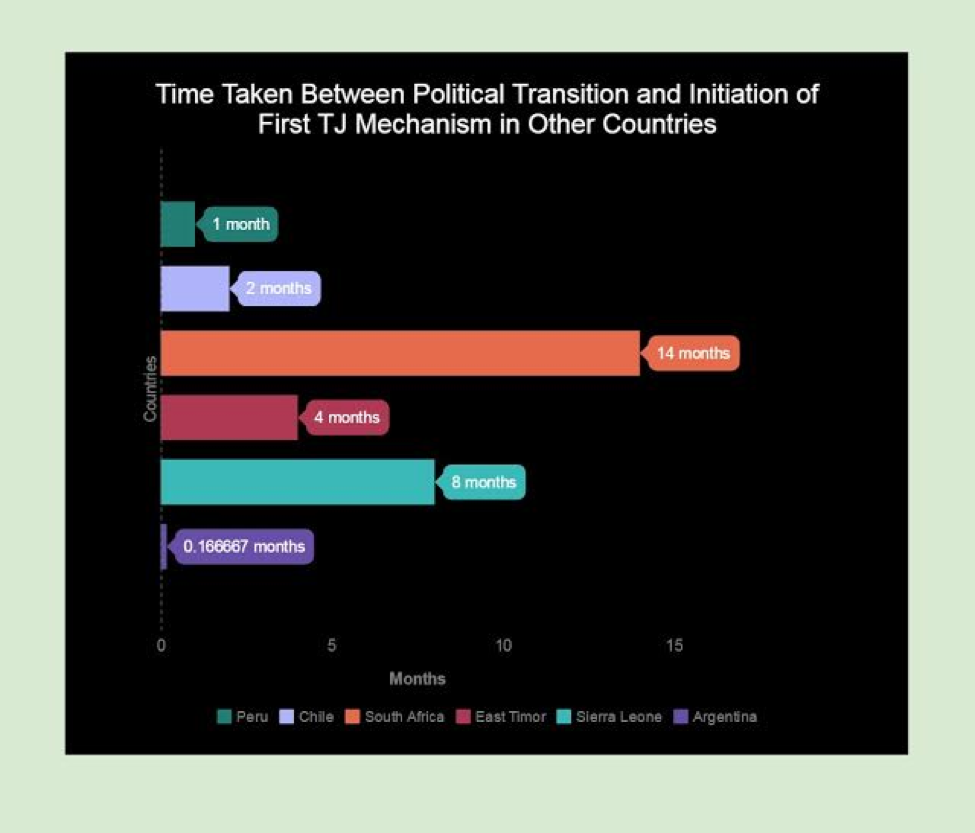

A brief survey of the TJ landscape in other countries demonstrates the wisdom of Minister Samaraweera’s political calculus. In countries that have come to be known for successful Transitional Justice processes, the time lapse between the initiation of the first TJ mechanisms and the “transitional moment” has been very short. Activists from Latin America often speak of the rapid urgency with which they urged their respective governments to move on TJ related issues, despite the numerous obstacles. By avoiding protracted consultation processes, and in cases such as Peru, by opting for Truth Commissions established by Presidential decree rather than ones established by legislative enactment which they imagined would involve considerable delay, they were able to maximize the energy, potential and momentum of the political transition to deliver results. In contrast, processes characterized by lengthy consultations—for instance, the process in Nepal took as much as 18 months—cannibalized exceedingly valuable momentum and political time. Today, the process in that country is floundering, and while these failures may be attributed to a number of causes, the loss of political momentum is indubitably a factor. While undue haste is never useful, neither is interminable delay, especially when success depends on utilizing steadily diminishing political space.

In Sri Lanka, the nascent pre-TJ process cannot possibly be accused of haste. Indeed, as the graph below demonstrates, Sri Lanka may already be an outlier in terms of the time lapse between the political transition in January 2015 and the initiation of TJ mechanisms. The government only publicly identified the TJ mechanisms it said it would implement in September 2015, just prior to the UN Human Rights Council session at which the OISL Report was released. The consultation process in this case was supposed to commence with a government-appointed Task Force assuming office in January 2016. The Task Force then constituted at least two committees to advise it on a range of issues, one on which I serve. It is expected to now constitute more Zonal Committees to conduct the actual consultations. Despite the Minister’s commitment to a three month consultation process, more than three months since the appointment of a Task Force, and nearly seven months since the passage of the UN Human Rights Council resolution in Geneva, consultations on the ground have yet to materialize. While the Task Force has sought the views of the public electronically and in writing, focus group discussions and community meetings have not been conducted yet.

This situation is rapidly approaching the critical. As time lapses and the government’s honeymoon with the public ends, bread and butter issues will assume centre stage, the country will revert to politics as usual, and the space for introspection and TJ will close. If the comparative lesson from other countries is to avoid delay, the particularities of Sri Lankan politics calls on an even more heightened sense of urgency. Implementing the most challenging parts of the Geneva resolution requires, at a minimum, some measure of Sirisena-Wickremasinghe (or SLFP-UNP) consensus. As those relationships fray and Sri Lanka looks to move beyond a brief interlude of cohabitation towards a more traditional SLFP vs UNP configuration, the prospect of success on TJ will be rendered more unlikely.

To expend all of the enormous potential of the limited political space opened up by the change of 2015 into a meandering process of consultations is a grave error of judgment and politics. Such an approach will inevitably give rise to allegations of deliberate sabotage. Consultations must be about producing action, not a substitute for it.

What then of consultations? Should we wait for its report before embarking on any measures? I would suggest not. For one, we simply cannot afford that luxury at this stage. The Minister is right: the legislative provisions to birth TJ mechanisms do not have to wait for the Task Force to conclude its work, whenever that may be. The design of a Missing Persons Office and a Special Court combine technical and political considerations. Many of the political factors relevant to the Court—the special court design, a special prosecutor, the retroactive incorporation of international crimes and the mixed nature of the court which should include foreign and national personnel as judges, lawyers, prosecutors and investigators—have already been negotiated in Geneva, before consultations even began. As long as the government fully and sincerely implements the Geneva consensus, it cannot be faulted. Other issues of a more technical nature require legal and technocratic solutions and are unlikely to benefit from the outcome of a public consultation process. With the Missing Persons Office, the major issues are largely technical, and the government has consistently maintained that it expects to establish the Office quickly. Second, both these institutions—the Court and the Office of Missing Persons—could however benefit from a consultation process in terms of how its officers operationalize the existing laws. For example, a Special Prosecutor could be assisted a great deal by the consultation process in crafting a prosecutorial policy. Thus, the adoption of legislation prior to the consultation process concludes does not render the consultation process irrelevant; it merely acknowledges that the major value of the consultation process will be for the animators of the mechanisms, not necessarily for its creators. Third, results from consultation processes are in any event often complex, multi-layered and lend themselves to further debate and discussion. They are thus unlikely to conclusively resolve any of the fundamental political differences concerning TJ.

The government should now utilize the opportunity of the Human Rights Council session in June by passing at least some pieces of special legislation to establish TJ mechanisms. Two in particular – the Missing Persons Office and the Special Court – do not have to wait. Instead, further delay in establishing the building blocks for these mechanisms jeopardizes the prospects of success, and the rapidly diminishing prospect of robust mechanisms.

The time to act is now.