by David Renwick, ‘Red Pepper,’ UK, January 6, 2018

Daniel Renwick calls for the whole movement to discover and remember the vital work of A. Sivanandan, who died this week

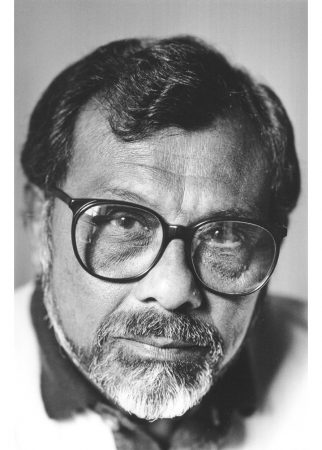

Ambalavaner Sivanandan (Siva) was not en vogue during my life. For activists and anti-racist campaigners of previous generations of the black struggle, though, Siva was a giant.

Ambalavaner Sivanandan (Siva) was not en vogue during my life. For activists and anti-racist campaigners of previous generations of the black struggle, though, Siva was a giant.

His presence was announced in so many ways: his polemic pamphlets launched like grenades into key battles like Grunwick. When you chart the struggles in Britain, and the writings, debates and interventions around them, Siva’s influence can be felt. However, with the changes that came with globalism, Thatcherism and financialisation, the uncompromising position he held meant he was sometimes seen as somebody who was stuck in the paradigms of yesteryear – a shocking misconception that needs rectifying now more than ever.

For Siva to have an influence in modern struggles, people have to know his name and seek out his work. Only radical veterans, generally outside of the academe, spoke of his immeasurable influence. The new generations of anti-racists didn’t seem to know him, even if they used his aphorisms.

Capitalism’s furnace

Siva made penetrating interventions on the issues that define our political moment. While he never used a computer, writing all of his works by hand, he understood what the microchip had done to global class relations more than the writers who embraced the technological revolution, which Siva recognised had a greater impact on human relations than the industrial revolution.

What Silicon Valley and the microchip enabled, Siva noted with great incision, was the shift of capitalism’s furnace, from the metropole to the periphery. Modern technology freed capital from labour, not the other way around. Automation and mechanisation put a proverbial gun to the head of the worker, empowering multinational corporations to eviscerate working conditions in a race to the bottom. Resistance from states or social movements seeking to curtail the power of multinational corporations meant they upped sticks and moved their plants to other, more pliable nation states or localities, where new populations were grist to the mill.

Globalism, Siva noted with force, was a project; globalisation was the process. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the world and social movements came to know ‘TINA’ (there is no alternative). This is what Mark Fisher later called ‘capitalist realism’ – the sense that resistance is futile and the world must learn to accept and embrace global capitalism.

For many, there was something to celebrate in this. The planned economies and political centralisation that communism bred into resistance movements had made it too cumbersome and flat-footed, but to Siva, conceding the ground of economic alternatives was a crime that could not be excused. To find salvation in identity, dress, fashion and plurality, while billions were impoverished by a global system was ‘hokum’. Stuart Hall, a friend and interlocutor of Siva and the Institute of Race Relations, was dealt caustic blow after caustic blow for his embracing of the ‘new times’, which Siva cut through as ‘Thatcherism in drag’. If you got on the wrong side of Siva politically, you would know it. He did not compromise.

It wasn’t just that political visions must be maintained, but that the mutations of history must be mapped, and systems of resistance to be re-imagined. Globalism made the distinction between economic migrant and refugee fatuous. The crises around the world around borders and migrations illustrate Siva’s point remarkably. Globalism tore the fabric of nation states to pieces and worsened living conditions, making emigration a necessity to those seeking betterment of their lives. Immigration to the West is therefore bound to what the West is doing abroad. The structural violence of the World Bank and the physical violence of NATO were two sides of the same coin that pushed millions to traverse borders. His maxim about the presence of former colonial subjects in the West can be re-read in the conditions of the present: ‘we are here because you were there’. Mass migrations continue on the basis of power dynamics based on colonial and imperial logics. Another of his great sayings comes to mind: ‘colonialism is not over, it is all over’.

Siva was a thinker who cut to the bone on the issues of migration, automation, globalism, identity politics, class and race. It is a scandal to me that those who claim to be versed in the schools of anti-racism are not screaming his name from the rooftops and making social media reverberate with his legacy. But such are the times. Siva did not write for the social media warrior. He did not concern himself with the race politics of representation. ‘The people we write for are the people we fight for,’ that was his school. He did not seek to put a veneer over a violent present – he sought to rip down the veil and push people to take action that empowered and amplified those at the coal face of the struggle. He encouraged people to work on lived theory – where social theory and academia engaged with the material conditions of those most persecuted and oppressed.

Water in a desert

The writings of Sivanandan are for me like water in a desert. His words encourage a criticality and fuel an anger to challenge a violent present, predicated on an even more violent past. While many writers fall into bad faith, convincing themselves that positive change can emerge through compromise, Siva encouraged radical and profound resistance to the world from the bottom up.

Identity, in and of itself, was a cul de sac. Racism, in his analysis, was a global class system that could only be overcome through major structural change. Diversity within the existing system was not progress to Siva. White navel gazing was mercilessly mocked with his engagement with racial awareness training, which he claimed reified race relations and locked whites into a mode of self-flagellation, when they should be encouraged to challenge the status quo and stand in solidarity with those on the picket lines, being deported or being held at detention centres. Switch a few referents and you have a profound engagement with the culture of allyship that underwrites white engagement with anti-racism in the modern day. ‘Who you are is what you do,’ he told whites who wanted to be part of anti-racist struggle, opening up the possibility of meaningful political engagement for those seeking a better world.

Many of those who loved and admired Siva have humorous stories of their first encounter with the man, his uncompromising engagement that was intimidating, to say the least, both intellectually and physically. He helped to teach so many lessons, and push the struggle forwards.

History, for Siva, was a dialectic. He did not confine this to the dialectal materialism of the dogmatic Marxists: he brought the Bhagavad Gita and TS Eliot to his dialectical analysis. The discursive turn taken in the late 20th century that made language the site of struggle frustrated him. Language was not the battleground, the world was. Structures needed to be changed, not language. Truths needed to be spoken, not narratives. He eschewed the idea that the personal was a realm for the political, reversing the dictum by saying the ‘the political is always personal’. Siva taught that political struggle is based on fighting with those who are the victims of the system and saw no merit in moving the furniture or window-dressing the butcher’s house.

The odds are stacked against liberation, he knew. Siva witnessed the ethnic violence of Sri Lanka, almost losing his life, before walking into the racial tensions of post-war Britain. He developed a humane, nuanced, powerful and deeply philosophical school of resistance, which continues through the work of the Institute of Race Relations, which he ripped from the clutches of global corporations and the foreign office.

The people influenced by him may not be as numerous as they should be now, but the tools he provided mean that many people are still trained to take aim at history. History, Siva told Colin Prescod in an interview a few years ago, is now moving too fast to catch on the wing, something any casual watcher of the news knows only too well. The task we have is to find where we can puncture the moment, where struggle worthy of the word can be forged and the system can be challenged.

For Siva, and those who follow him, this is as local as it is global. It is fighting to keep a local library, it is fighting for public space, it is fighting against deportations, it is standing in solidarity in Calais, it is fighting the struggle in the wake of the Grenfell fire, it is standing firm against nativism and border politics when the colonial past casts such a deep shadow over our present.

To end on one of his most powerful aphorisms, ‘If those who have do not give, those who haven’t must take.’

Red Pepper will be publishing further tributes to Sivanandan and explorations of his legacy in the coming weeks

2009 profile by Arun Kundnani — https://www.redpepper.org.uk/viva-siva-1923-2018/