Grave secrets

by Indunil Usgoda Arachchi & Vimukthi Fernando, ‘The Sunday Observer,’ Colombo, August 19, 2018

Sunday Observer journalists visit a grave excavation in Mannar, where forensic investigators are hard at work, painstakingly unearthing human skeleton after skeleton, determined that this time, the investigation into the suspected mass grave site will not be compromised- politically or scientifically

MANNAR: The site is tucked into the corner of two busy streets, fenced by metal; the entrance hidden from view. Blue tarpaulin covers the entire site, shielding it from the scorching midday, when excavators are at their busiest. Through a narrow opening, visitors must walk single file to reach the excavation site before the bones become visible.

Human skulls, femurs, hands, feet and entire skeletons protrude through the soil about 1.5 meters below the entrance to the dig. They appear to be strewn, some turned sideways, others, piled up haphazardly.

A female forensic archeologist hovers over a tiny skeleton, a proportionately small set of tools in her hand – a brush with soft bristles, a toothbrush and a few other instruments that resemble those on a surgical table. Painstakingly, she brushes sand off each piece of tiny bone, pouring tiny drops of water to remove stubborn pieces of dirt and handling the remains like a mother would handle an infant. As she works, part by part, the human skeleton begins to emerge and take shape.

A female forensic archeologist hovers over a tiny skeleton, a proportionately small set of tools in her hand – a brush with soft bristles, a toothbrush and a few other instruments that resemble those on a surgical table. Painstakingly, she brushes sand off each piece of tiny bone, pouring tiny drops of water to remove stubborn pieces of dirt and handling the remains like a mother would handle an infant. As she works, part by part, the human skeleton begins to emerge and take shape.

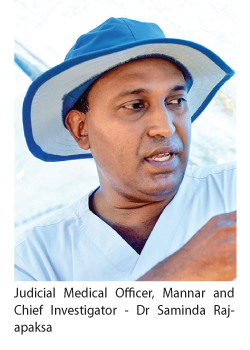

Dr Saminda Rajapaksa stretches out a hand to stop visitors to the site from going any further. Chief Investigator of the excavation site and Judicial Medical Officer, Dr Rajapaksa says by Magistrate’s order, those with permission may walk up to the edge of the excavation, but no further. Only forensic specialists and investigators will handle the remains, in order to protect the integrity of the bones ahead of carbon dating and possible DNA testing.

On March 25 this year, a complaint was lodged with the Mannar Police, when human bones were discovered at a construction site on the CWE (Sathosa) premises. Investigation of the site began under the supervision of Mannar Magistrate T.G. Prabhakaran. Excavations began on May 28, after investigators determined that the area contained undisturbed skeletons. The excavation team comprises consultant JMOs, Prof. Raj Somadeva, a forensic archeologist, officers from the Government Analyst’s Department, police, Survey Department and staff from the Mannar Municipal Council. Police Scene of Crime Officers are in charge of photographic recording of the site.

Each time multiple human remains are discovered in Sri Lanka, they bring up old questions. Tens of thousands of people are still recorded as missing from two insurgencies and a 26 year civil war. Mass grave sites have been discovered all over the country – Matale, Sooriyakanda in Embilipitiya, Chemmani in Jaffna, and even in another location in Mannar four years ago, when 30 skulls emerged fuelling speculation that the site could provide answers about thousands who went missing during the war. Nearly every time, the discovery of bones has led to prolonged excavations and shipping them off for carbon dating and other tests. Every time, the investigations reached no firm conclusions.

This time, Dr Rajapaksa is hoping, will be different.

If the chain of custody was not strictly maintained in previous suspected mass grave investigations, anyone could raise questions and make allegations. I am committed to finishing this investigation without raising such doubts. If necessary, I will accompany the bone samples to a lab overseas personally, to ensure authenticity and the integrity of the remains are not compromised,” Dr Rajapaksa told Sunday Observer, during the dig last week.

If there are mistakes linked to previous investigations, the scientists had to ensure they did not happen here, he insisted.

Bone samples are scheduled to be sent for testing at the Beta Analytic Radio Carbon Dating Lab in Florida USA for carbon dating. However, results of the carbon dating tests of the Matale mass grave conducted at the Beta Analytic Radio Carbon Dating Lab in Florida USA, was criticised by forensic experts. Lawyers and civil society groups in Mannaralso stopped the move to send samples of the Thirukethiswaram mass grave site to the same lab. But according to DrRajapaksa, these doubts could be cleared by ensuring the chain of custody is undisturbed.

On Friday, August 10th, the excavation had reached the 52nd day. Investigators had identified 81 skeletons, with 72 completed skeletons already excavated. Seven skeletons identified as children have been excavated so far. Adult males, females and adolescent remains have also been unearthed.

The work ongoing at the site is monumental, and deeply significant in a country in which a long internal conflict has cast long shadows and deep scarring. But according to investigators like Dr Rajapaksa, time is also of the essence. The forensic specialists begin work at 7AM every day, and sometimes continue till after dark, using bright electric floodlights to illuminate their work space.

Investigators say that at this juncture, dating of the find is of paramount importance as it will be key to future decisions about investigations at the site. The sooner the samples are sent for carbon dating, the better. The excavation crew is awaiting financial allocations for this purpose from the Ministry of Justice.

The reason for this urgency is because skeletons that had been underground for so long would damage easily when exposed. “The skeletons were found about a foot above the sea level and it seems some are below the sea level. Water seeps into part of the site, where human bones were first found as it is below sea level. Two pumps are used to keep the water away 24 hours. Even algae could threaten the remains. However, we try to minimise the threats and carry out the investigation scientifically and as close to international standards as possible,” one investigator told Sunday Observer.

The investigation of this suspected mass grave site, are conducted at two levels – excavation and analysis. The present stage is excavation. Already, DrRajapaksa says, forensics specialists have discovered two kinds of burials at the site – formal and informal. “The informal burial site is where skeletons were found overlapping, irregular, and in multiple layers of skeletons, so these take priority in further investigations,” the Chief Investigator explained.

According to forensic archeologist, Professor Raj Somadeva, the suspected mass grave is marked by the lack of evidence of ritualistic burial. “The arrangement of the skeletons is not of a ritualistic burial site. When a Hindu person dies, they perform rituals building a fire and breaking a water pot. There was no evidence of ritual objects such as pot shards or charcoal that tends to mark ritual Hindu burial sites,” Prof. Somadeva pointed out.

Prof. Somadeva says the artifacts found at the grave site belong to three different periods. While some date back to 5th or 6th century AD, others belong to the Dutch era and the rest to the modern period. “The assemblage of artifacts provides a complicated picture representing different time zones. We are interested in sorting out the three phases clearly. Therefore, a relative date could not be stated until we finish the report,” he explained.

The site of the discovery of bones itself is complicated. There are no records relating to the building that was torn down. The Mannar Magistrate has ordered authorities to hand over building plans, but investigators have not yet received them. According to residents in the area, the property was always owned by the Marketing Department or the CWE.

The site of the discovery of bones itself is complicated. There are no records relating to the building that was torn down. The Mannar Magistrate has ordered authorities to hand over building plans, but investigators have not yet received them. According to residents in the area, the property was always owned by the Marketing Department or the CWE.

Investigators explain that photographs and the diagrams being meticulously recorded will help reconstruct the situation layer by layer. “We would try to depict it as a 3D image in the final report as this grave is of national and international interest. This could be the first mass grave investigation where 3D view is enabled. The documentation would help identify levels, the position of each bone and skeleton in relation to the rest,” he explained.

Open graves and excavations have begun with great enthusiasm and interest in the past, but have almost always led to disappointment and more questions than answers. Virtually, in every case – Sooriyakanda, Matale and Chemmani – the final reports were suspected to have been compromised and questionable. For families of the missing, scattered across this tiny island nation, every discovered mass gravesite, each unearthing of bones, brings fresh torment and fear.

Perhaps it is for this reason that the permanent Office of Missing Persons, set up by an Act of Parliament in 2016, has stepped in to supervise the current excavations in Mannar. In its first attempt to fulfill part of its mandate to trace the missing, the OMP decided to fund and facilitate logistics of the forensic investigation at the Sathosa premises in Mannar earlier this month. This would include food and transport facilities for investigators among other logistical support.

According to OMP Chairman Saliya Pieris, once investigations and carbon dating is complete, the Office may look into matching DNA of the discovered bones with DNA samples obtained from families of the missing, particularly in the Northern Province.

V.S. Niranjan, a lawyer representing families of the disappeared in Mannar, said the victim families would have preferred it if the excavation was being overseen by international experts. Niranjan says over 300 families who have lost loved ones believe the Mannar CWE remains could be linked to their cases. “We are going to file affidavits. That’s the next step. Of course, we have to go through several institutions to do that, so it’s a long process,” the lawyer explained. The legal battle waged by families of missing persons on the suspected mass grave site found in Mannar in 2014 is still not settled says Niranjan. “It is difficult to make them understand their loved ones may never come back. Some are still clinging to the last threads of hope.”

But all this is far removed from the forensic investigators, who must apply patience and meticulous rigour to their work on the bones. Sitting beside skeletons for hours, with small tools and brushes, investigators wash, dry and arduously prepare the bones for storage. Once the skeleton appears, it is photographed and the position of each bone is sketched, and an in-situ forensic description is made as part of the analysis and for the records. Thereafter, the skeleton is removed section by section, each bone is washed, dried labelled and placed in an airtight bag. A full set of bones belonging to each skeleton is placed in a cardboard box, labelled and stored. For security reasons, the remains are stored at the Magistrate’s Court in Mannar.

Dr Rajapaksa says that at their pace, the investigators are only able to remove one or two skeletons a day. This must be done with great care, he says, causing no damage whatsoever to the bones. “It’s time consuming, but we want to do this as scientifically and transparently as possible.”

Pix: Thilak Perera