by Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka, January 13, 2020

Credible Information gathered by the International Truth and Justice Project – Sri Lanka (ITJP) and JDS reveals how the new government of Sri Lanka under a majority Sinhala hardliner has embarked on its strategy to militarise and securitise the country, unleashing a chilling process of repression targeting critics and human rights defenders within less than two months in office.

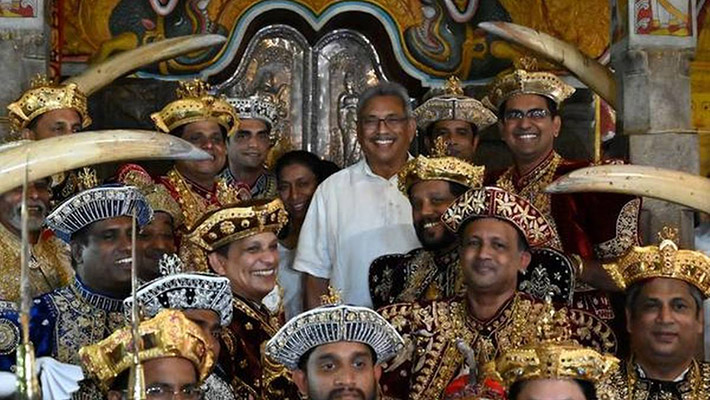

Gotabaya Rajapaksa elected as the president in mid-November has repeatedly emphasised that his priorities would be serving the majority Sinhala Buddhists and boosting the country’s security.

Shrinking of civic space

The latest report by ITJP and JDS, “And the Crackdown Begins”, reveals that almost 70 Incidents of Intimidation and threats have taken place before and after the elections targeting journalists, human rights defenders, lawyers, plaintiffs, academics and opposition figures. In some cases the threats have been so serious the individuals have fled the country.

“What we are seeing is the dismantling of any attempts to address accountability and a massive shrinking of the civic space in Sri Lanka with even more sophisticated and intrusive surveillance,” said ITJP’s Executive Director, Yasmin Sooka.“The international community has to ensure the increased security assistance it is giving Sri Lanka after the Easter Sunday bombings is not being misused now to crack down on human rights defenders and journalists”.

The new President’s strategy is to securitize and militarize Sri Lanka through appointing many of his former war time cronies in the military to key posts in state institutions and to take over functions normally handled by the police, says the report.

ITJP and JDS describe this as President Rajapaksa “spreading his tentacles”. Those involved in investigating past crimes including fraud have been removed from their posts.

‘Deep state’ in the open

The report reveals a systematic clampdown by the police, army and intelligence services in Sri Lanka intended to terrorize and deter human rights activists and the media from documenting and reporting on issues of justice and accountability. The crackdown also targets Sinhala journalists in a post-election spate of retaliation against those perceived to have supported the opposition.

“Individuals previously accused of corruption or alleged to be involved in war crimes are now in office again – the ‘deep state” is out in the open, occupying positions of authority,” said Bashana Abeywardene of JDS, adding that it’s cast a pall of silence over once outspoken journalists, trades union activists and human rights activists.

The incidents have been documented with the help of activists in Sri Lanka who cannot be named for their own safety.

© JDS

SRI LANKA: AND THE CRACKDOWN BEGINS

CONTEXT

On 16 November 2019, Sri Lankans went to the polls resulting in the Sinhala majority electing

Gotabaya Rajapaksa their President. As the former powerful war-time secretary of defence for a

decade, Mr. Rajapaksa was a key figure in the war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

(LTTE), in which the UN says war crimes and crimes against humanity were allegedly committed by

state forces under his control. Mr Rajapaksa was far more than a civil servant, as a former military

officer himself and brother of the then President, he issued direct orders to commanders on the

battlefield and police officers.

In his election campaign, Gotabaya Rajapaksa promised to protect the Sri Lankan security forces

from being held accountable for war crimes and crimes against humanity that occurred during and

after the country’s civil war1. Mr. Rajapaksa’s return to power was premised on the notion that Sri

Lanka needed a strong man to take on terrorism and bring back security after the Easter Sunday

bombings in Sri Lanka. Unfortunately, as President of Sri Lanka, he enjoys head of state immunity

so long as he holds the post of President.

STRATEGY

The new President’s strategy is to securitize and militarize Sri Lanka through appointing many of his

former war time cronies in the military to key posts in state institutions and to take over functions

normally handled by the police. The new Government’s policy is to suppress any dissent and to crush

any demands by the international community or domestically for justice and accountability for past

crimes committed during the decade long conflict with the LTTE.

In this context he has also promised to rehabilitate alleged perpetrators close to him and has already

appointed many individuals previously accused of corruption or alleged to have committed war

crimes in his inner circle to key positions of power (see diagram). It is worth noting several

appointments also come from Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s former military regiment, the Gajaba Regiment.

1‘“A large number of war heroes are languishing in prisons over false charges and cases. I would like to declare at this moment that they will all be released by November

17th morning,” Rajapaksa said.’, Gotabaya pledges to release imprisoned war heroes by Nov. 17, Adaderana, 9 Oct 2019.

http://www.adaderana.lk/news/58267/gotabaya-pledges-to-release-imprisoned-war-heroes-by-nov-17

Pivotal to his strategy for rehabilitating his allies is an extraordinary presidential gazette notification

(2157/44) of 9 January 2020, signed by Presidential Secretary P. B. Jayasundera, in which Gotabaya

Rajapaksa establishes a Commission of Inquiry to look into political victimization “instigated through

a special unit dealing with Anti-Corruption “between 8th January 2015 and 16th November 2019. This

paves the way for those previously accused of corruption, including the President’s Chief of Staff, to

be exonerated.

Furthermore, Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s current strategy is to target those organisations and individuals

who document, report and litigate on behalf of victims, especially Tamils in the former conflict areas

and to crush any opposition and suppress dissent. Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s militarization and

securitization policy has been calculated and well-orchestrated. The pre-election incidents set out in

this report, were a precursor to the systematic, ruthless campaign of repression waged since his

election.

Human Rights Defenders, journalists, and trade union activists have expressed concern at the

intelligence collected insidiously through the “Occupation Information Sheets”2

they are being required to fill in, detailing home and office ownership and leases, staff and inhabitants and their

National Identity Cards, vehicle details. The state already has data from the last census and the

electoral register.

The information collected for this report reveals a systematic clampdown by the police, army and

intelligence services in Sri Lanka intended to terrorize and deter human rights activists and the media

from documenting and reporting on issues of justice and accountability. The crackdown also targets

Sinhala journalists in a post-election spate of retaliation against those perceived to have supported

the opposition.

INTERNATIONAL ASSISTANCE

The context to this crackdown, which intensified in the run up to elections because significant figures

in the security forces supported Gotabaya Rajapaksa, is the increased securitisation after the Easter

Sunday bombings. In the wake of the bombings, which targeted three churches and three hotels and

killed 253 people, questions have been raised about grave local intelligence failures. The response

of the international community has been to offer increased support to the police in Sri Lanka while at

the same time reminding the Sri Lankan authorities of their need to be human rights compliant. This

approach does not factor in the routine use of torture in police interrogations which the UN as well

as the US State Department and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth annual human rights reports

have detailed for decades and may be perceived to condone torture.

Furthermore, governments who are assisting Sri Lanka with its counter terrorism measures after the

bombings should be extremely cautious in their support to the Sri Lankan regime, lest they be

perceived as facilitating a crackdown on human rights activists whose work has nothing to do with

the bombings and terrorism and whose activities they have encouraged and supported up until now.

The increased securitization has resulted in suppression of freedom of information and movement

for local human rights defenders and an erosion of democracy.

THE LEGAL COVER FOR SECURITIZATION

In the wake of the Easter Sunday bombings a State of Emergency was declared3

and thousands of troops deployed for civilian policing duties, many of the units now led by officers implicated in serious

international crimes and violations4. This emergency arrangement lapsed on 21 August 2019 and

2 See sample at https://twitter.com/gajenmahen/status/1215479993377214464

3 Sri Lanka declares state of emergency, grants army new powers after Easter attacks, 22 April 2019, France 24,

https://www.france24.com/en/20190422-sri-lanka-attacks-nationwide-emergency-terrorism-security

4 See ITJP and JDS Lanka, The Men Now Patrolling Sri Lanka, May 2019, http://itjpsl.webfactional.com/assets/press/2019_may_the_men_-

now_patrolling_sri_lanka_itjp__jds.pdf

was replaced by a series of extraordinary gazette notifications5 issued by the President calling out

the army, navy and air force to maintain public order. The most recent gazette issued on 21

December 2019, intentionally legalises the role of the military in the securitization and militarisation

of the state including through arrogating to themselves policing duties even though an extensive

police and intelligence network already exists in the former conflict areas with sophisticated intrusive

and extensive surveillance capabilities.

It also comes in a context where the President, the Secretary of Defence, the Chief of National

Intelligence (CNI) and the head of the Special Intelligence Service (SIS) come from the military, either

as serving or retired military officers. This is significant because the SIS and CNI jobs have previously

been held by policemen, not soldiers. This against the backdrop of the police in 2013 having been

placed under the authority of a new Ministry of Law and Order following international pressure to

normalise the security establishment. Following the November 2019 elections the police have

reverted back to the control of the Ministry of Defence because although 54 ministers6

have been appointed nobody was appointed as Minister of Law and Order. This appears to be part of the remilitarisation of the state, including the policing function in Sri Lanka. A number of police officials

have privately expressed their deep concerns to journalists astonished that they themselves are the

subject of surveillance by the military that now has more power than the police in day to day security

affairs.

The control and oversight of the security forces involved in the incidents listed in this report rests

squarely with the President who controls the defence portfolio which includes police, intelligence and

military7. The current State Minister of Defence is Chamal Rajapaksa (brother of the President)8, the

Prime Minister, another sibling is Mahinda Rajapaksa9, the President (and Minister of Defence) is

Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the Secretary of Defence is a long-time ally of the President who fought in

the same regiment in the eighties and directly under his command in 2009 when alleged war crimes

were committed10.

RISKS IN DATA COLLECTION

The incidents in this report have been compiled by Sri Lankan activists who cannot be named

because of the serious risks they face to their personal safety, and the 69 incidents are most likely

only a fraction of the total number of incidents reported on. The information was collected up until

the end of December 2019.

Key details of the institutions and individuals who have been targeted have been redacted for their

safety, except where that information is already in the public domain. Though a detailed spreadsheet

documents the incidents that have taken place, it is not being shared given sensitivity and witness

protection concerns.

5 22 November 2019, by Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The previous ones by President Maithripala Sirisena.

21 December 2019, by Gotabaya Rajapaksa, http://documents.gov.lk/files/egz/2019/12/2154-54_E.pdf

6 38 of them state ministers – see next footnote. 28 Ministers at http://documents.gov.lk/files/egz/2019/11/2151-38_E.pdf NB. Some individuals hold multiple portfolios.

7 “31 institutions including the Department of Immigration and Emigration, the Identity Card office, NGO Secretariat, Telecom Regulatory Commission, National Media Centre, National Building Research Institute and even the Weather Department have been placed under the Defence Ministry. Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa has been gifted 88 institutions while Minister Chamal Rajapaksa has been granted 26 institutions. Since Chamal Rajapaksa is also the State Minister of Defence (no Cabinet minister has been appointed), the Rajapaksa brothers are in control of 145 institutions.” (http://www.ft.lk/columns/The-Unravelling/4-691664) Specified in gazette: http://www.documents.gov.lk/files/egz/2019/12/2153-12_E.pdf

8 Official Gazette notification of appointments at http://documents.gov.lk/files/egz/2019/12/2154-55_E.pdf

9 http://documents.gov.lk/files/egz/2019/11/2151-18_E.pdf

10 See Dossier on the Secretary of Defence: http://www.itjpsl.com/reports/kamal-gunaratne

PRE ELECTION INCIDENTS

NGOs in Colombo and the north and east of the island who work on issues like enforced

disappearance, Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) detention and land rights are once again under

intense scrutiny and have started receiving threatening visits from security officials in the months

leading up to elections. Of the 33 pre-election incidents collected, which are by no means

comprehensive, the visits intensified sharply in October 2019.

In 9 cases the officers who harassed or intimidated NGO staff introduced themselves (showing CID

identity cards) or were known to be from the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the police;

in 2 cases from the Terrorism Investigation Division (TID); in 5 cases they were believed to be from

intelligence and in another 6 cases the policeman’s identity or station was known to the NGO. Some

NGOs even have the names and phone numbers of those who harassed and threatened them.

The chart summarises the incidents reported – those targeting NGOs and journalists as well

as some focused-on lawyers and plaintiffs in ongoing court cases, and a number of

opposition politicians and allied figures.

The questions asked by different security officials during these interrogations and interactions were

consistent across different areas of the country, suggesting that an order had been given from high

up to gather specific information. NGO staff were asked for the registration documents of the

organisation, details of donors and funding sources, international links, details of employees

(including broken down by gender and organisational structure) and activities, especially work on

disappearances or connected to litigation. In some instances, NGO staff reported being followed by

plain clothes officers when conducting their field work. Others noted receiving sudden visits from

security officials or being harassed by anonymous calls on their mobile phones.

“I got to know from their inquiries they have been told by the Defence Ministry to report on our work

on disappearance to other units like the TID, Military Intelligence and State Intelligence Service who

will also investigate us”.

One NGO staff member was even advised by the police to leave their job and seek employment in

another sector if the government changed. These ominous visits, menacing threats and intimidation

as well as the interrogation of NGO staff suggests a systemic plan.

POST ELECTION INCIDENTS

NGOs

The intimidation and threats to NGOs have continued well after the 16 November elections.

Organisations continued to be visited by police officers who interrogated staff members on whether

they had sent information abroad to international organisations and demanding to know who their

funders were. Questions were asked of several organisations about events being planned for

international Human Rights Day (10 December).

Increasingly the questions are focused on individual NGO staff and their whereabouts; some have

been summoned for questioning or in a few instances, hunted down so extensively that they were

forced to flee the country.

JOURNALISTS AND MEDIA FREEDOM

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) described the last Rajapaksa government from 2005-15 as the

“dark era” for media freedom in Sri Lanka.

A range of incidents targeting mostly pro-UNP activists and web journalists have been reported in

the first weeks of the new government. Some media offices faced raids in which their computers and

phones were unlawfully seized. One reporter described being called by a known official in the

government and warned not to publish stories about the war and about accountability. Journalists for

Democracy in Sri Lanka quoted the Internet Media Action (IMA) alleging the raids on the media

offices were unlawful and conducted without a valid court order11

. On 22 November 2019, Tamil journalist Sakthivelpikkai Prakash, editor of Thinappuyal

newspaper, was interrogated over his coverage of the war and asked, to provide the contact

details of all his reporters, which he refused to do12

. On 26 November 2019, the office of Newshub.lk was raided13 and police searched their

computers for the word “Gota”.

11 http://www.jdslanka.org/index.php/news-features/media/919-fear-grips-journalists-after-new-sri-lanka-president-targets-opposition-media

JDS further reports: ‘The Free Media Movement (FMM), Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA) and the Professional Web Journalist Association (PWJA) denouncing the police action have highlighted that they are not challenging the authority of CID to question citizens for a valid reason.“Nevertheless, we believe that questioning journalists for hours, raiding premises and offices that house websites, without a valid reason or even a legally valid court order, is a formidable pressure

on media freedom,” said IMA convener Sampath Samarakoon.’

12 https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/sri-lankan-police-question-tamil-newspaper-and-demand-staff-details

13 Reportedly with an expired warrant from the previous year.

On 26 November 2019, the leader.lk YouTube channel newsreader Sanjaya Dhanushka

was subjected to an eight-hour interrogation by CID Cyber Crime Division.

On 29 November 2019, voicetube.lk journalist Thushara Sewwandi Vitharana was summoned

and interrogated by CID for 6 hours reportedly after a complaint made by a Sinhala Buddhist

organisation that backed Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s election campaign14

. On 4 December 2019, Convenor of Sri Lanka Social Media Association, Nuwan Nirodha Alwis,

was visited by police in his home15

. On 6 December 2019, Daily Mirror and Lankadeepa correspondent in Aluthgama Thusitha

Kumara de Silva and his wife Anusha Kumari were assaulted, their home stormed by armed

men, money and a mobile phone seized; a former UNP minister alleged on social media that

a current minister was responsible16. District journalists stood in solidarity with the couple to

demand justice. Five alleged assailants have been arrested17

. On 10 December 2019, Maduka Thaksala Fernando of the New Media Department of the

state-run Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. was assaulted even though he’d offered his

resignation after the elections to make way for a new political appointee18

. On 15 December 2019,Lasantha Wijayaratne who wrote a pro-UNP book on corruption under

the Rajapaksa period, was reportedly beaten and had a gun put to his head by two persons

wearing motorcycle helmets obscuring their faces who asked him “don’t you see any good in

any of the Rajapaksa projects?”19

. On 19 December 2019, journalist Prasad Purnamal was assaulted20. In a separate incident

on the same day, state run media journalist Gayan Pushpitha was assaulted while covering

the arrest of former Minister, Patali Champika Ranawaka21. The alleged assailant was seen

in a video in a local government vehicle; the local government is under the control of the SLPP.

Sri Lankan journalists fear new gov’t silencing dissent. 11 Dec 2019,

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/sri-lankan-journalists-fear-new-gov-t-silencing-dissent/1670591

Presser by Dhanushka Ramanayake & http://www.jdslanka.org/index.php/news-features/media/919-fear-grips-journalists-after-new-sri-lankapresident-targets-opposition-media

14 http://www.jdslanka.org/index.php/news-features/media/919-fear-grips-journalists-after-new-sri-lanka-president-targets-opposition-media

15 Letter to President published in fb https://www.polkade.lk/%E0%B7%83%E0%B6%B8%E0%B7%8F%E0%B6%A2-

%E0%B6%A2%E0%B7%8F%E0%B6%BD-

%E0%B6%B8%E0%B7%8F%E0%B6%B0%E0%B7%8A%E2%80%8D%E0%B6%BA%E0%B7%80%E0%B7%9A%E0%B6%AF%E0%B7%93-

%E0%B7%83%E0%B6%82%E0%B6%9C%E0%B6%B8/

“Two uniformed police officers and three in civvies who identified themselves as police officers who said they are from police headquarters

questioned me about my media activities during the past period and questioned about websites that they themselves have decided were owned by me.”

16 http://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking_news/Daily-Mirror-Lankadeepa-journo-family-attacked-by-armed-gang/108-179247

http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=215107

17 http://www.ft.lk/news/Five-suspects-arrested-for-attack-on-Aluthgama-journalist-remanded-until-20-Dec/56-691454

18 https://www.wsws.org/sinhala/2019/2019nov/lswj-21n.html

19 https://www.wsws.org/sinhala/2019/2019nov/lswj-21n.html

20 SLWJA press release and local journalists and protesters https://twitter.com/vikalpavoices/status/1207935567037632513

21 SLWJA press release https://twitter.com/vikalpavoices/status/1207935567037632513

Although it is not reflected in the 2019 data, the Tamil Guardian reporter in Batticaloa, S. Nilanthan,

was threatened and summoned to court in January 2020 in connection with his reporting on

corruption22. Predictably, the UNP has failed to defend the media even those journalists that had supported them;

defeated presidential candidate and opposition leader, Sajith Premadasa was reported as expressing

support for the new President’s policies23.

Social Media

Two key twitter accounts – one Tamil and one Sinhala24 – closed down or ceased activity in the first

week of the new government out of fear. They were both important news sources.

Several activists reported being suddenly trolled in a systematic fashion on twitter in the first week –

some said the trolls had pictures of Gotabaya Rajapaksa on their mastheads and most abuse was

from accounts created in November or December 2019.

22 https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/sri-lankan-police-charge-tamil-guardian-correspondent-over-reporting-local-government

23 UNP ready to support implementation of GR’s policies, 18 Dec 2019,

http://colombogazette.com/2019/12/18/unp-ready-to-support-implementation-of-grs-policies/

24 https://twitter.com/maratnasiri/media and https://twitter.com/garikaalan/status/1197543839046615042

The abuse included physical threats and misogyny directed against women and started literally

overnight:

Many activists resorted to locking their accounts or to self-censorship. As the Canadian High

Commissioner to Colombo tweeted, there was a definite silencing on twitter:

SWISS EMBASSY

The abduction of a female Tamil visa officer working in the Swiss Embassy has been extensively

reported on. Switzerland is the only country in Sri Lanka to offer in-country humanitarian protection

visas to Sri Lankans. This incident has resulted in victims being fearful to approach the Swiss

Embassy, given well founded concerns about how secure their sensitive personal data is now that

one of the key visa personnel has been in custody. The said official is reported to have said that she

was forced to hand over the pin to her phone, which had applicant details on it, and the contents

were reportedly downloaded. This suggests that the surveillance by the security forces using

information technology is systematic, well planned and coordinated. Many activists have asked

whether the equipment and software being used now against them, NGOs and journalists was been

provided by foreign governments for counter terrorism.

The Government of Sri Lanka has subsequently demanded that Switzerland extradite the CID officer

Nishantha de Silva who is reported to have sought asylum in Switzerland. At one point bizarrely, the

Special Task Force of the police are reported to have raided the offices of their colleagues in CID,

seeking the case files prepared by Inspector de Silva. Other key CID officers who worked with

Inspector de Silva on the emblematic cases under the Sirisena government have been transferred

or are being investigated25 and are unable to leave the country. A great deal of fake news is

circulating about the policemen and their links to groups abroad.

25 SSP Shani Abeysekera interdicted, Daily Mirror, 7 Jan 2020,

http://www.dailymirror.lk/top_story/SSP-Shani-Abeysekera-interdicted/155-180873

IMPACT

Human rights activists allege that individuals and groups who have actively advocated for war time

accountability including truth recovery on the enforced disappearances are the ones being targeted.

The government’s strategy is to sow terror and intimidation and suppress dissent which many fear

will prompt human rights defenders and critics of the Rajapaksa family to leave their jobs or even the

country, if they can. Self-censorship is already setting in. Lawyers have postponed court hearings,

while victim support groups say they are struggling to find people to accompany victims to police

stations or hearings as everyone is scared.

Human Rights Defenders have expressed their fears that this is actually the honeymoon period and

that following the parliamentary elections – expected in the coming months – there could be a more

serious crackdown in which anyone expressing dissent or advocating for justice and acountability

will be silenced. The lack of commitment and failure by the Sirisena regime to implement the

transitional justice programme they committed to including security sector reform has resulted in

military officials complicit in war crimes being returned to power and consequently the erosion on a

daily basis of the rule of law.