Tamil Guardian editorial, London, November 4, 2019

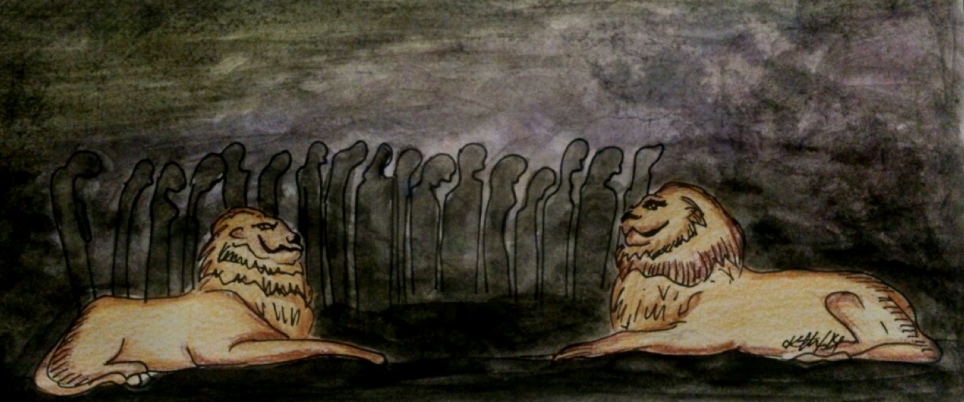

Artwork by Keera Ratnam.

As Sri Lanka gears up for a presidential election in just a few weeks time, Tamils on the island find themselves faced with a familiar decision. Almost five years after an election that was hailed as the dawn of a new era for Sri Lanka, the island has instead seen pledges of reforms broken and the failure to address key issues towards accountability, justice and a lasting peace. With leading candidates choosing to boast their Sinhala nationalist credentials, for Tamils in particular, the future seems bleak.

Those who claimed that the United National Party’s (UNP) and Sirisena’s 2015 election victories would see the end of the Rajapaksa dynasty were wrong. Sri Lanka’s infamous former defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa has demonstrated that his brash firebrand version of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism still has a widespread appeal across the Sinhala masses, that has only grown in recent years. He now stands as the firm favourite to become president. During his tenure, Rajapaksa stands accused of committing atrocity crimes that included bombing hospitals and enforced an era of repression across the North-East that violently targeted Tamils through murders and abductions. The chilling prospect of a Rajapaksa return has rightly left many Tamils fearful.

The alternative however, does not look much better. Sajith Premadasa may be hailed by some in Colombo as a moderate, but his policies on key issues are no different. An equally fervent Sinhala Buddhist nationalist, he has matched Rajapaksa’s pledge to bolster Sri Lanka’s deeply problematic intelligence network. Premadasa even vowed to create a new post – National Security Advisor – that would be occupied by Sarath Fonseka, who as commander of the army was Rajapaksa’s right hand in 2009 and stands accused of many of the same charges. He has also been ardent in his support of troops accused of war crimes, exemplified by his bold declaration that he would protect current Commander of the Army Shavendra Silva – a man dubbed Sri Lanka’s most wanted – “no matter what” international pressures he faced.

Throughout the course of this presidential campaign, both candidates have made their stance on accountability resoundingly clear. A decade on, the army’s massacre of Tamils in 2009 is still seen in the south as a ‘victory’ and not as the genocidal onslaught that it is becoming increasingly recognised as. No matter what the result of next month’s polls, the perpetrators of mass atrocities will still be praised as heroes. And there will still be no justice.

The position of the leading candidates comes as no surprise. Indeed, it is reflective of how little progress has been made over the last four years on core Tamil issues. Despite the unequivocal support of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) and unfettered goodwill of the international community, the current regime has made virtually no progress on accountability, demilitarisation or devolution of powers. The much lauded Office of Missing Persons remains powerless and has been silent for months. The constitutional reform process has all but entirely stalled. And multiple UN Human Rights Council resolutions look no closer to implementation than they did when Colombo first co-sponsored them in 2015.

Even the most basic of demands put forward by a broad spectrum of Tamil political parties including the TNA, have now been roundly ignored or outright rejected by Sinhala candidates. The front runners have also deliberately refrained from being seen as making overtures to Tamil demands, in apparent fear of losing Sinhala votes. Despite this, the ITAK leadership at the 11th hour has chosen to continue its support for the UNP, endorsing Premadasa, but emphasising that the demands they had signed off which were considered essential to the Tamil constituency, were not part of any negotiation process. This hollow decision, which immediately drew protests, essentially tells Tamil voters that their demands do not matter in this election, continuing the state’s long history of complete disregard and broken promises.

It is no wonder then that many Tamils have been left disillusioned with Sri Lanka’s political process, with some even calling for a boycott. While fear of a Rajapaksa return will likely be a driving factor for Tamils voting in this election, a traditionally low voter turn-out in the North-East is not likely to increase in the face of this blatant indifference from the presidential candidates.

On November 16th, Tamils will once again find themselves mercy to an electoral process driven by Sinhala nationalist politics, and left once more with no real choice. This is nowhere more evident than in the tattered shelters along the roadside in the North-East, where on that same day, Tamil families of the disappeared will mark the 1000th day of their protest, resisting a government that pays them no heed.