T Kumar memorial booklet – Kumar Mama Booklet Document

Thambithurai Kumar

For Kumar, who died on Martin Luther King Day, the struggle of one person, race, gender, caste or nation could never be viewed in isolation. He believed that a problem for one person or group, was a problem for all human beings. Kumar staked his entire professional career on that belief. He also lived it out at every level of his life.

T. Kumar Memorial Service Day 1 – https://www.youtube.com/live/xnvvg8nbD7Y?si=cqv7GDqoF459Fl2o

T. Kumar Memorial Service Day 2 – https://www.youtube.com/live/y8wUJ31t4YQ?si=wuBLm_V_GDFiJWy0

Condolence Statement by P2P Movement – Muthukumaraswamy__Kumar_Anna_

T. Kumar, Rights Activist Who Was Shaped by Time in Prison, Dies at 76

After being jailed as a resistance organizer for the Tamil minority in his native Sri Lanka, he spoke out against governmental repression worldwide.

“He truly believed in the rule of law, and justice, and that people deserve justice from their elected governments,” a peer said of Mr. Kumar.Credit…Ben Hider/Getty Images

by Adam Nossiter, New York Times, January 29, 2026

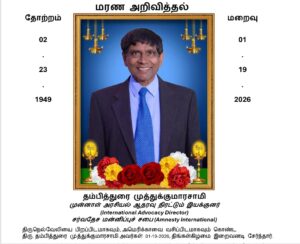

Thambithurai Muthukumarasamy, a human-rights activist who went by T. Kumar and whose advocacy for victims of governmental repression around the world was inspired by his years spent in Sri Lanka’s prisons for his work as a resistance leader, died on Jan. 19. He was 76.

His death was confirmed by Amnesty International, where Mr. Kumar worked for over 20 years, including serving as director for international advocacy and advocacy director for Asia. The cause was complications of sarcoidosis, an inflammatory condition, his sister Krishnal Muthukumarasamy said in an interview. He lived in the Washington, D.C., area but it was unclear where he died.

For years Mr. Kumar spoke out, in congressional testimony, at the United Nations and elsewhere, against China, Vietnam, Afghanistan and other countries whose governments, justice systems and prisons had violated their citizens’ rights.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, he told a congressional committee that the “Taliban’s Shariah courts and religious police” in Afghanistan “impose cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment.” He told another committee in 2017 that in Vietnam, “prisoners of conscience were tortured and otherwise ill-treated, and subjected to unfair trials.”

As a young man, he spent more than five years in various stints in the prisons of his native Sri Lanka — repeatedly arrested, beaten and ferried from jail to jail because he was an outspoken student leader for the persecuted, predominantly Hindu Tamil minority.

After his death, the online news site Tamil Guardian called Mr. Kumar “a key organizer and political thinker” of the early Tamil resistance movement.

Mr. Kumar’s resistance efforts and imprisonment in the 1970s foreshadowed the bloody civil war in Sri Lanka that began in earnest in 1983 and lasted over a quarter-century, ending in a 2009 massacre in which hundreds of Tamils were killed in the country’s north by the largely Buddhist Sinhalese regime. By then Mr. Kumar had long since emigrated to the United States.

He had a fervent belief in the law — so much so that he spent years in tiny prison cells studying for admission to law school in Sri Lanka, an effort that finally paid off.

“I don’t doubt that what drove him to being such a great advocate was his own experience,” Mona Dave, a senior program officer for Asia at the National Endowment for Democracy, said in an interview. “He truly believed in the rule of law, and justice, and that people deserve justice from their elected governments.”

Thambithurai Muthukumarasamy was born on Feb. 23, 1949, one of eight children of Thambiturai Muthukumaraswamy and Maruthapraveegavalli Muthukumaraswamy.

He was born in Thirunelveli, the town where, 34 years later, a deadly Tamil attack on Sri Lankan Army soldiers triggered the start of the civil war. As a child he lived in the cities of Jaffna, Batticaloa, Kandy and Colombo, moving around since his father was a traveling senior judge on the Sri Lankan judicial circuit.

According to Mr. Kumar’s 2025 memoir, “From Political Prisoner to U.N. Advocate: The Extraordinary Story of T. Kumar,” written (in the third person) with Omar Ahmed, his political consciousness was awakened by witnessing discrimination against Tamils from an early age.

He “was among those involved in the formation of the Students’ Council, which played a foundational role in transforming spontaneous resistance into organized political activity,” according to Tamil Guardian.

Though the students’ protest was peaceful, Mr. Kumar, as the president of the council on an increasingly restive campus, was repeatedly questioned by the police and was finally arrested and imprisoned without charge in 300-year-old Fort Hammenhiel. For the young prisoner, it was less brutal than it might have been.

“All of the students were treated like heroes in the prison when we walked in,” Mr. Kumar said in a 2013 interview with WAMU radio, adding, “I was very well taken care of by the guards, because they were also ethnic Tamils.”

Mr. Kumar’s 2025 memoir. He had a fervent belief in the law — so much so that he spent years in tiny prison cells studying for admission to law school in Sri Lanka, an effort that finally paid off.Credit…T. Kumar

His case attracted attention beyond Sri Lanka’s borders. Amnesty International named him a prisoner of conscience, a special designation for nonviolent political prisoners, and organized a worldwide campaign for his release.

Amnesty singling him out “had a role in him coming to understand that there is a global movement for human rights,” John Sifton, the Asia advocacy director at Human Rights Watch, said in an interview.

Mr. Kumar was released from Fort Hammenhiel after six months thanks to the attention from Amnesty. But he continued to speak out about the plight of the Tamils, and was rearrested within months.

This time, he was imprisoned in southern Sri Lanka, far from his home. There were no Tamil guards looking out for him.

“We were abused,” he said in the 2013 interview. “We were tortured, beaten up.”

He became more religious and began to focus on studying the law. After going on a hunger strike, and after pressure from other Tamil leaders, Mr. Kumar was released after more than two years, according to his memoir.

He was finally allowed to begin his law studies, finished after three years, entered private practice and focused on defending Tamils. But intensifying repression forced him to flee Sri Lanka; he traveled through Malaysia and Africa, staying with relatives, and procured a U.S. visa from a sympathetic American ambassador in Botswana.

In the United States, he entered the law school at the University of Pennsylvania, earning a law degree there in the early 1990s and beginning his work with Amnesty.

Mr. Kumar is survived by his wife, Sivaneswari Muthukumarasamy; his sister; and five of his other siblings.

In addition to his advocacy work with Amnesty, he lectured at the Foreign Service Institute, the U.S. government’s training center for diplomats and other members of the foreign service, and monitored elections around the world with former President Jimmy Carter.

Adotei Akwei, a senior adviser at Amnesty International, said in an email that Mr. Kumar was “the human rights survivor who had the grace and strength to continue fighting without fear or bitterness and went on to shape almost anyone who encountered him.”

T Kumar, former political prisoner and veteran activist, passes away in Washington

by Tamil Guardian, London, January 26, 2026

Veteran Eelam Tamil activist Thambithurai Muthukumarasamy passed away in the United States earlier this month, bringing to a close the life of a man who spent decades on the frontlines of human rights advocacy.

Known affectionately as T. Kumar, his political life spanned the formative decades of Tamil resistance, from the emergence of militant consciousness among Tamil youth in the early 1970s to sustained international advocacy for justice and accountability in the decades that followed.

Muthukumarasamy belonged to a generation that came of age at a time when constitutional politics had collapsed for the Tamil nation, and when state repression had rendered peaceful protest both ineffective and dangerous. As a member of the Tamil Student Movement, he was part of the radicalised youth milieu that responded to systematic discrimination, cultural erasure, and state violence by seeking new political pathways beyond parliamentary engagement.

This was a period in which early armed fighters of the Tamil Eelam liberation struggle operated as fragmented and independent groups, often without formal structure or coordination. Yet it was also a period of decisive political awakening. The defiance embodied by Pon Sivakumaran, whose sacrifice electrified Tamil youth, and the organisational momentum generated through the Students’ Council initiated by Ponnuthurai Saththiyaseelan, marked a historic turning point. It was within this crucible that Muthukumarasamy emerged as a key organiser and political thinker.

He was among those involved in the formation of the Students’ Council, which played a foundational role in transforming spontaneous resistance into organised political activity.

The early years of the armed struggle were marked by intense state repression, and Muthukumarasamy was not spared. He was subsequently arrested by the Sri Lankan security forces, whilst he was still a student.

Muthukumarasamy endured imprisonment in some of the most notorious detention facilities of the time, including Jaffna Fort Prison and Kandy Bogambara Prison.

.jpg)

In a 2023 interview he described how “Amnesty International adopted me as a Prisoner of Conscience and initiated a worldwide campaign, putting pressure on the Sri Lankan government to secure my release”.

“A Prisoner of Conscience is someone who has not used or advocated violence in the circumstances leading to their imprisonment,” he said. “They are imprisoned due to who they are, whether that is their ethnicity, race, sex, economic status, social origin, or what their religious, political, or other conscientiously held beliefs are. Under international human rights law, one cannot be detained without a legitimate reason, and all have the right to a fair trial but in many countries, there are no safeguards in place to ensure this.”

Following his release, his commitment to memory and resistance found expression in a deeply symbolic act. It was by his own hands that the first statue of Pon Sivakumaran was inaugurated at Urumpirai.

His life and struggles also entered the realm of Tamil political literature. Thambithurai Muthukumarasamy was the central character in Langarani, a novel written by Arular (Arul Prakasam), one of the founders of EROS. The novel offers a stark portrayal of state repression, political betrayal, and the injustices carried out under the guise of democracy by the Sri Lankan state, capturing the moral and political environment in which early Tamil militants operated.

In later years, Muthukumarasamy migrated to the United States, where his struggle took on a different but no less significant form. A qualified attorney-at-law, he devoted himself to international human rights advocacy, bringing the lived experience of political imprisonment into global legal and institutional spaces.

He served as Amnesty International’s Advocacy Director for over 22 years, and worked as a human rights monitor across multiple regions. He also served as a Professor at the Academy of Humanitarian and Human Rights Law at Washington College of Law, educating new generations of lawyers in the principles of humanitarian law and accountability.

His work extended into international election monitoring, where he served as an Election Judge in Philadelphia. He also functioned as an Advisor to the United Nations Quaker Office and provided advisory input on United Nations related affairs to the Transnational Government of Tamil Eelam (TGTE).

Throughout these roles, Thambithurai Muthukumarasamy embodied a rare continuity. He was part of a generation that moved from underground resistance to international advocacy, yet never detached its legal and humanitarian work from the political roots of Tamil oppression.

Recognised as one of the patriarchs of the armed struggle in Eelam history, Thambithurai Muthukumarasamy leaves behind a legacy defined by personal sacrifice, and unwavering commitment to justice.

.jpg)