Tortured by police, separated from his family for years, but Tamil refugee still says nandri – thank you

Rescued after 22 hours in freezing water, Para Paheer applied for asylum in Australia. An extraordinary friendship with a Victorian woman helped ease the pain of waiting eight years to see his wife and son

Para Paheer and his wife Jayantha, who have been reunited in Australia after nearly eight years of forced separation after Sri Lanka’s civil war. Photograph: Ben Doherty for the Guardian

by Ben Doherty, ‘The Guardian,’ UK, December 24, 2017

Paheer’s near decade-long search for safety and to be reunited with his wife and child has been marked by trial and tribulation, but it is nandri – Tamil for thank you – that he reaches for first upon reflection on his journey.

He was born in 1978, to a labouring Tamil family in a small village in Sri Lanka’s north, a green and fertile land that would come to know nothing but brutal civil war for almost all of his life there. His family slept on the floor of their mud house and his parents drew what they could from their small, overworked plot of land. His single blue school uniform was faded to nearly white from being washed every afternoon.

Ben Doherty

They had no electricity, so Para did his schoolwork by the light of a hurricane lamp. But a house at the other end of the village had a television and, as a child, Para crept over there to watch the movie Tarzan. He was caught by his father, and beaten for sneaking out when he was supposed to be doing his homework.

The second time he was caught, his father didn’t hit him but sat him down and told him: “Look around you – this is poverty. We are all poor here, no one goes to university, no one has a good job … You have a good brain; if you work hard, you can break out of this.”

Burning vehicles near the town of Mullaittivu during the Sri Lankan civil war between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam separatists. Photograph: Ho New/Reuters

Para never went back to the television. But while he attended school with the children of his village, Sri Lanka’s civil war raged, fought between government forces and the Tamil Tigers who fought for an independent homeland in the country’s north.

When Para was nine, his father was arrested, beaten and interrogated on suspicion of being a Tamil Tigers’ sympathiser. He was not, and was ultimately released.

At the same age, Para watched dumbstruck as a terrified young Tamil man was bound, interrogated, then shot in the street by the Tigers on suspicion of collaborating with the government.

He walked to school one day to find the gates closed and, by them, two heads stuck on long spikes, their eyes open and staring, and smothered in flies.

“I still don’t know who those people were or why they had been killed,” he says.

Amid the violence, life found a way. Para became a prefect at his school, and graduated third in his district, winning a place at the University of Jaffna to study economics.

There he met Jayantha, a fellow economics student, one who had been promised to a marriage overseas she did not want. Paheer proposed she marry him instead. But she was high caste, he was low caste, and her family did not agree to the marriage.

After months of consideration and in defiance of her family, Jayantha agreed to marry Paheer. But the mores of conservative northern Sri Lanka forbade a declared relationship while they were still students. They kept their betrothal secret for three years.

After months of consideration and in defiance of her family, Jayantha agreed to marry Paheer. But the mores of conservative northern Sri Lanka forbade a declared relationship while they were still students. They kept their betrothal secret for three years.

Jayantha was not interested in the politics of Sri Lanka’s war: she wanted only that the fighting stop. Paheer, however, had been politicised by his time at university: he attended protest rallies against the government’s restriction and repression of Tamils and found himself running for student president.

“Jayantha warned me, ‘This will cause problems if you make this choice.’ But I felt I had to, because of what was happening to my people.”

Paheer won the election and, as Jayantha predicted, his elevation to an overtly political position brought him immediately to the attention of Sri Lankan government forces.

Above the ordinary harassment experienced by Tamils in Sri Lanka – being stopped and searched at army checkpoints, subjected to curfews and harassment at random – he was now a target, surveilled by security forces and threatened.While he was never a member of the Tamil Tigers, they sought to exert an influence on him too, as a direct link to Jaffna’s student population.

After university, Paheer and Jayantha married and took jobs teaching on Mannar Island, in Sri Lanka’s north-west. But Paheer’s past followed him, as he feared it would: one day a white van – the unmarked vehicles without number plates were notorious for snatching people from the streets – came for him.

He was bundled into the van, beaten by police and told he was to be executed. But the local bishop, who knew Paheer from the Christian school where he taught, intervened and told the soldiers, “He is just a teacher, he is not a soldier or a spy. I can vouch for him.”

Paheer was dumped on the roadside but warned he would not be alive much longer.

With a baby due, the couple needed to leave the north. The same bishop smuggled them through the military checkpoints, and Paheer and Jayantha settled in the Sri Lankan capital, Colombo. He found a job working at the harbour fish market. Their son, Abi, was born in 2007.

But the war was at yet another peak, and the paranoia of the security forces was at an apogee. The violence was unpredictable and few places in the country were safe. When a bomb exploded in a neighbouring suburb, Paheer was hauled in again, and this time tortured by security forces.

He was released from prison – again, after the entreaties of friends and colleagues – but he realised Sri Lanka was no longer safe for him. With his young family he fled to the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Their situation there was little better. Their three-month visa quickly expired and they found themselves ever-fearful of being deported back to Sri Lanka.

As the net tightened around them, , Paheer and Jayantha decided he should flee for a safe country. “We could have no life where we were. I needed to make a life for my family, for my son.”

They chose Australia.

Paheer says there is broad misunderstanding about why people around the world board boats for a new country. The narrative of people seeking economic advantage, or to rort an immigration system, could not be further from his experience or of those who journeyed alongside him.

“People know it is very risky,” he says. “But … no one climbs in a boat, or puts their children in a leaky boat, without a reason – they think the water is safer than their land.”

Paheer’s boat was the first that attempted to leave the Indian mainland directly for Australia. But the people smugglers who took what little money he could afford peddled the same lies, promising smooth passage and a seaworthy ship. “They said, ‘Whoever goes to Australia by boat, they could bring their family in three months.’”

When Paheer arrived at the beach south of Chennai only one of the two vessels looked seaworthy. He went to board the larger, stronger-looking boat but relatives encouraged him to take the smaller one with them. Three days out, the larger boat fell out of radio contact. That boat, and the hundreds on board, were never seen again.

Siev (suspected illegal entry vessel) 221 being forced against a cliff during the 2010 Christmas Island boat tragedy in which up to 50 asylum seekers died. Photograph: WA coroner/AAP

But Paheer’s journey foundered too. After 20 days at sea, and with food and water running low, the boat sprang a leak. Passengers and crew baled for hours but, as the boat sank further into the waterPaheer – one of the few on board who could speak English – made a distress call to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. Help was hours away and the boat – given the appellation by Australian authorities Siev (suspected illegal entry vessel) 69 – was sinking. “A friend asked me, ‘Para can you swim?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’” Holding to an empty oil drum, Paheer jumped in.

The hours in the open waters of the Indian Ocean passed slowly. Paheer clung to his drum, others to gas cylinders and pieces of wood. One by one, people were dispersed by the waves and the currents, spread out over hundreds of metres. One by one, people disappeared under the waves and didn’t resurface.

It was 22 hours before the LNG Pioneer hove into view, and Paheer was dragged from the water. Twelve of his boatmates were never found.

Having been at sea nearly three weeks, Paheer was unsure of the passage of time. He asked the date: it was 2 November.

His birthday.

***

Ali Corke, a Victorian, heard news reports about Sieve 69 sinking, 500km off the Cocos Islands, and wondered what she could do.

Through Regional Australians for Refugees she volunteered to be an electronic pen pal with an asylum seeker held in detention. She drew Paheer.

His initial email began very formally: “Dear Madam.” She gently corrected him: “Please, think of me as your Australian mum.”

The second was better: “Dear Mum.”

Corke, with little knowledge of Sri Lanka’s violence, and Paheer, with a bare understanding of the country he intended to call home, gradually drew each other into their respective worlds, their families and histories, hopes and fears.

“It started off with an email every couple of days,” Corke says, “but it soon became two or three a day, even just quick ones about what we were doing. I wrote especially if he’d written he was feeling downcast or worried about something.”

From a distance, Corke watched Paheer deteriorate as the uncertainty of indefinite detention and the separation from his family took their toll.

“He’d say sometimes, ‘I think I should commit suicide,’ and I’d say, ‘Don’t talk like that.’” Important dates were especially hard. For his birthday we had every member of the whole family write him a happy birthday message.

“Because he did become a member of our family. And I made sure I never left it too long to write or send a message. That’s what you do with your kids.”

After two years in detention, Paheer was released. Formally recognised as a refugee, he moved in with the Corke family in 2011 and began re-establishing a life interrupted, finding work, improving his English and, most importantly, working towards reuniting with his wife and son.

He found work quickly: he cleaned homes, factories and hotels before taking a job in the Nauru immigration detention centre in 2013 as a cultural adviser assisting Tamil detainees – men like him who had sought sanctuary in Australia but who were now subject to the regime of offshore detention.

“I could see the same thing was happening to many people, the detainees on Manus and Nauru. Everyone had the same problems, the same frustrations, people were trying to commit suicide. The same long process … I could see it affected not only me.”

Back in Australia, Paheer found the job he still holds at Geelong University hospital, working as a ward assistant in the intensive care unit. But being reunited with his family was more difficult.

After several years, as Paheer approached the end of the byzantine application process, he was told, without warning, the government had “deprioritised” his application because he had arrived by boat, and he would go to the bottom of the pile. Having believed he would be away from Jayantha and Abi for a matter of months, their separation became a year, then three, then five, then indeterminate.

Paheer saw a psychiatrist in Australia. “I couldn’t sleep, I lost weight, I couldn’t concentrate at work. It affected me physically and mentally. And I couldn’t let Jayantha know how I was feeling because she was already in trouble, and she was very frustrated. It was hard for her, looking after our son all by ourself.”

Life for Jayantha, as a single mother in conservative southern India, was crushingly difficult. Leaving the house was often a trial, making even the simplest task – photocopying an identity document, visiting a high commission – a serious risk. She had no family support: the day she married was the last time her parents spoke to her.

Para Paheer reunited with Abi and Jayantha after nearly eight years apart

“It was hard for her to even leave her house, because of the very conservative culture, a single woman being out of the house is something that people are hostile about.”And Jayantha was truly alone. She had no family support – the day she married Para was the last time her parents spoke to her.But Jayantha and Paheer found a way. On Australia Day 2017, he became an Australian citizen. Seven months later, more than seven and a half years after they were separated, Jayantha was granted a visa to Australia.The Paheer family was finally reunited permanently in November.

They are finding their way in their new country. Jayantha’s English is steadily improving, helped by long chats with Corke. Abi is enrolled in an Australian school: on his third day he won a prize for mathematics. Paheer’s health has improved. He sleeps better now. “Before, I was worried always, till two or three or four o’clock. Now, I fall asleep at nine o’clock, straight away,” he says, laughing.

And Paheer is, without ever intending to be, an ambassador for refugees in the Australian community, according to Corke.

“People who don’t know any refugees, or who might be hostile to them, when they meet Para, their attitude changes. ‘Oh, I like you Para,’ they say. One by one, Para is changing hearts and minds.”

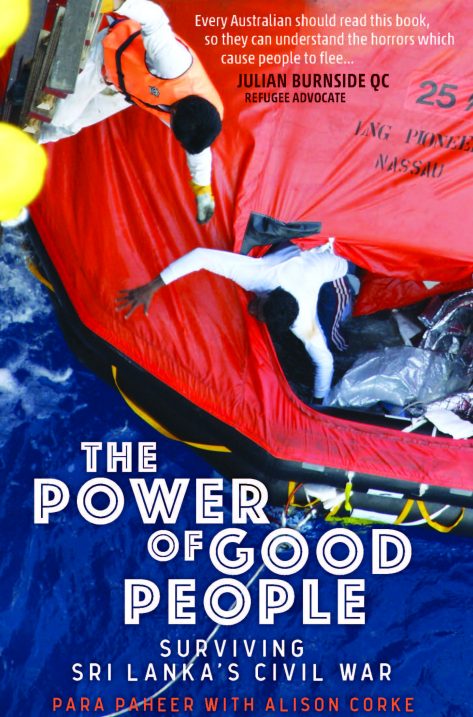

At Corke’s suggestion, Paheer has written a book with her to acknowledge those who have helped his family, in large ways and small, along the way. At his insistence it is called The Power of Good People.

To them, he says: “Nandri.”

• The Power of Good People: Surviving Sri Lanka’s Civil War by Para Paheer with Alison Corke is available through Wild Dingo Press

Many thanks! please do not give up! I hope that after many many years i might link up with Sangam in US. It is unfortunate that a few (million, perhaps) have lost the command or even basic use of Tamil language and can only give and receive information in English! Good Speed in 2018. Thanks, Ranjan

An eye opening article and information to countries that support the oppressive and genocidal Sri Lanka that continues to refuse to investigate forced disappearances, cold blooded murders by state forces and Sinhala hooligans, rape and torture of thousands of innocent civilians and genocide to date.

Sri Lanka, a small nation with extreme criminal and hate minded Buddhists like in Myanmar and Japan that behaved during second world war, continues to commit heinous crimes against humanity with impunity as International community is either totally incompetent or fully endorsing genocidal policies of the Sinhala Buddhist Apartheid state.

World has not civilized even after several genocides including Armenian, Rwanda, Eelam, Rohingya as International community is wasting time in talking absolute nonsense with criminal regimes instead of taking bold action against them like US nuked Japan during second world war or George Bush ordered military onslaught against Serbia to bring Milosevic to the ICC to deliver justice.

History will tell in bold fashion that World failed to have brave, fair, strong talented forceful and common sense leaders in 21st century as many genocides not been prevented as heinous crimes are not challenged by the so called international community. No wonder blood s shed all over the world in Eelam, Kashmir, Manipur, Punjab, Syria, Iraq. Libya, Sudan, Palestine and many nations that were never in the history of the world as a result of incompetent and insensitive international community leaders who are failed leaders of 21st Century!.

A serious question arise as to why would corrupt, incompetent, chauvinistic, weak and failed people are appointed as leaders of a global body when it requires strong, talented, brave, forceful and powerful leaders to stand firm on principles, fair, save humanity and take bold action?

WikiLeaks has exposed many war crimes, inaction by leaders although heinous crimes were known to them, double standard policies applied, oppressive actions were ignored although it was known. UN is undemocratic in many ways as it does not represent each race based on their numbers (over 100 million Tamils have no representation or voice at the UN), dictators and oppressive regimes are members of UN, alleged war criminals are allowed to speak at the UN, small nations with little population that rely on rich nations for their survival, support/voice/vote in favour of funding nations and not based on principles. Democracy is a failure in many nations due to illiteracy, corruption, oppression, two failed parties controlling politics, caste and discrimination and India is a classic example and one of the worst democracies on earth. Western colonialism that imposed their Apartheid and racist rule on other nations, merged many small nations as one for easy rule (today British voters voted for BREXIT, separation from EU) that led many races lose their freedom, dignity, respect. values, culture, democracy, rule of law, sovereignty and Justice. UK despite made a mockery in merging and leaving nations together, when there were solid evidence of state oppression against minorities / races that lost their sovereignty as a result of colonialism mockery, UK leaders allegedly collaborated to genocidal and oppressive regimes including Sri Lanka and India.

Good governance is failing all over the world due to Western double standard and Apartheid policies and UN has been a failure since its inception. No wonder North Korea has no confidence in western democracies and International Community.

God bless victims!