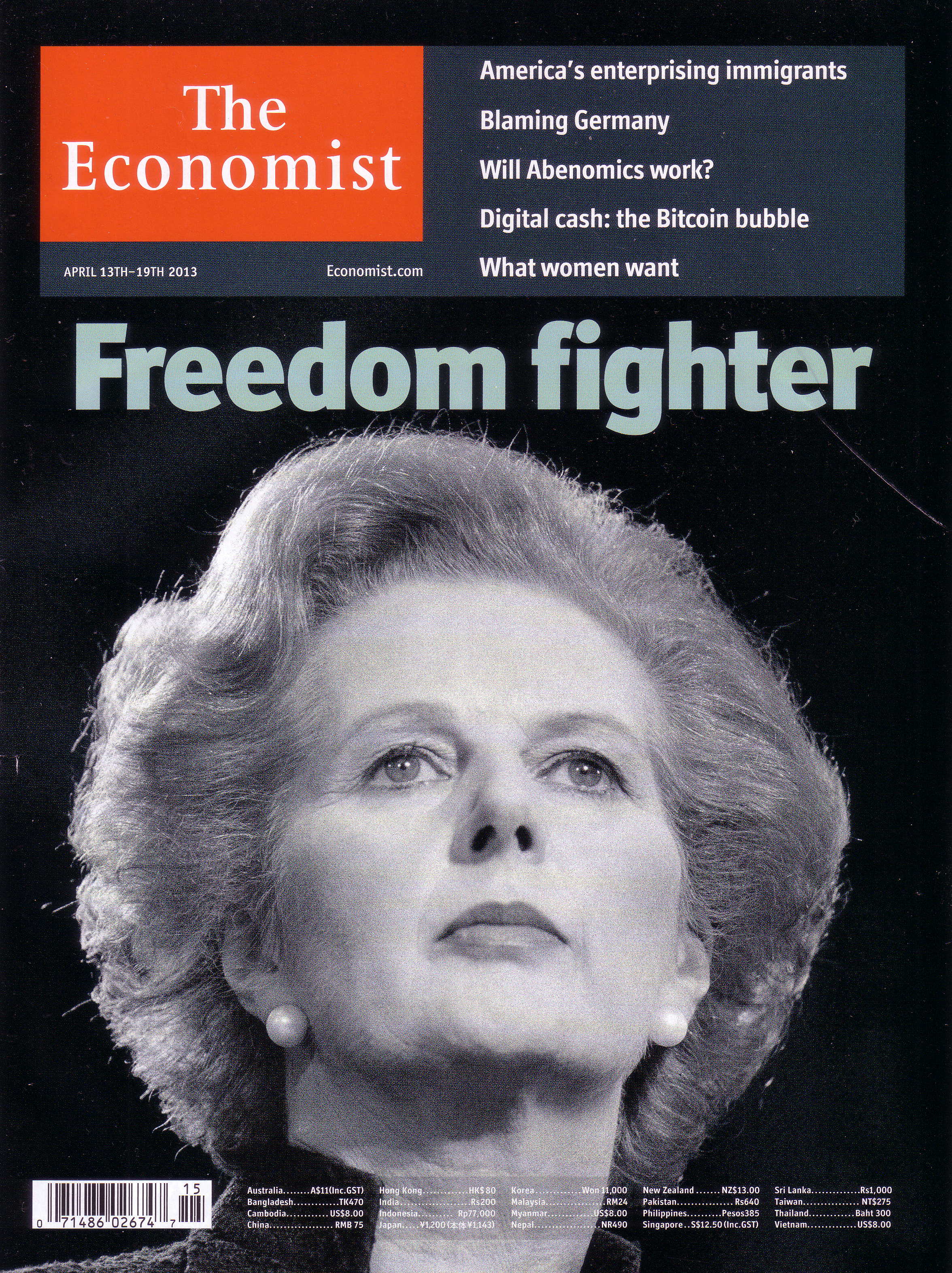

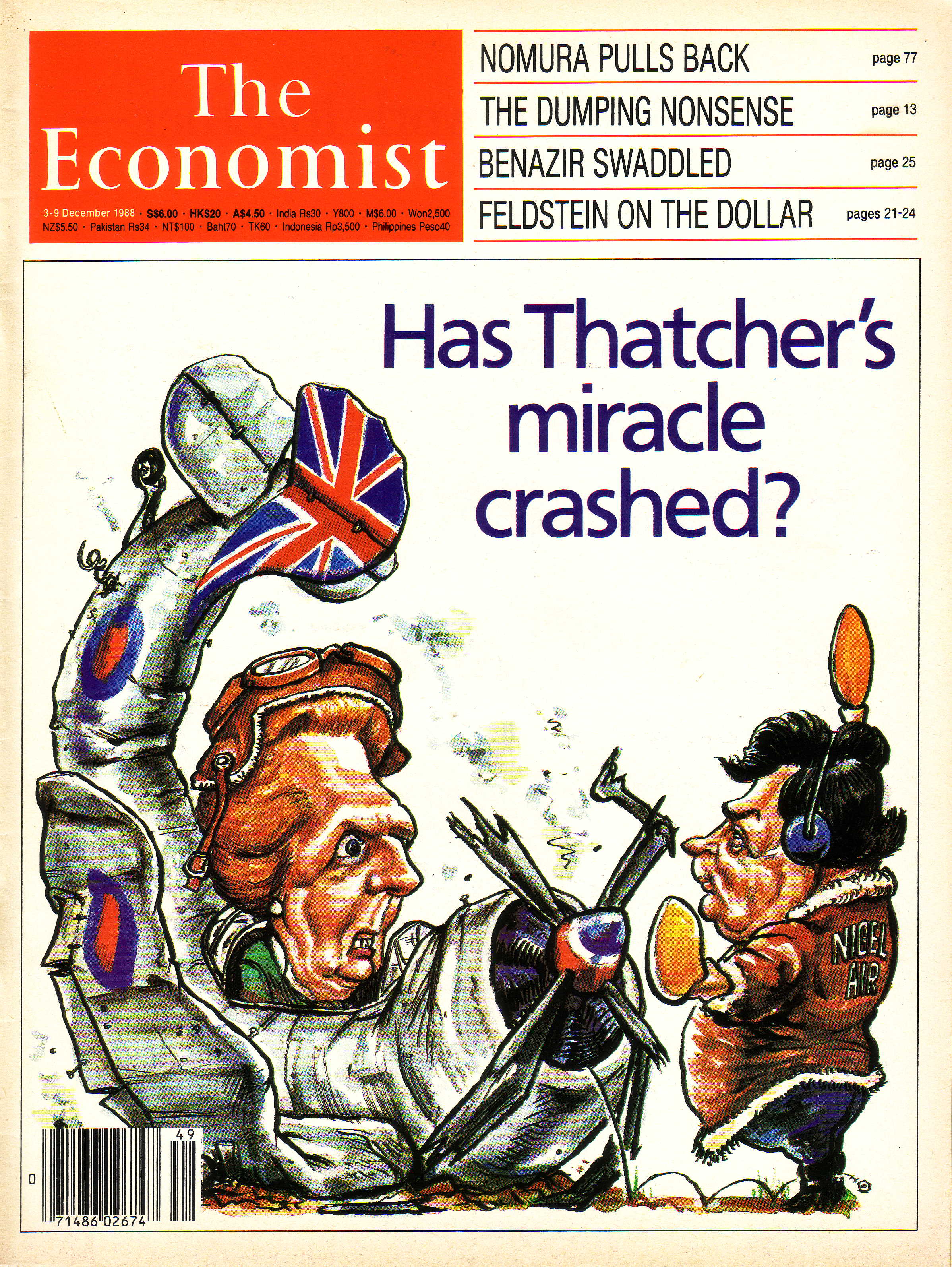

The editor and the cover designer of the Economist weekly (April 13, 2013) have a load of gall and a crooked sense of humor to tag, late Margaret Thatcher as a ‘freedom fighter’ in its homage to ‘The Lady’. If Thatcher was a ‘freedom fighter’, where does one place the likes of Nelson Mandela and his contemporaries in Asia and Africa? Two years before her eviction from the prime minister post, the same Economist magazine, featured Thatcher in the cover, with the caption, ‘Has Thatcher’s miracle crashed?’ (December 3, 1988) I’d settle for the tag that Thatcher was a freedom sniper, and not a ‘freedom fighter’; a cartoon of her with guns was again presented in its April 29, 1989 issue. I present below some evidence, related to Tamil refugees in 1985 and her meeting with Nelson Mandela in 1990, to show that Mrs. Thatcher was indeed a freedom sniper and not a ‘freedom fighter’.

The editor and the cover designer of the Economist weekly (April 13, 2013) have a load of gall and a crooked sense of humor to tag, late Margaret Thatcher as a ‘freedom fighter’ in its homage to ‘The Lady’. If Thatcher was a ‘freedom fighter’, where does one place the likes of Nelson Mandela and his contemporaries in Asia and Africa? Two years before her eviction from the prime minister post, the same Economist magazine, featured Thatcher in the cover, with the caption, ‘Has Thatcher’s miracle crashed?’ (December 3, 1988) I’d settle for the tag that Thatcher was a freedom sniper, and not a ‘freedom fighter’; a cartoon of her with guns was again presented in its April 29, 1989 issue. I present below some evidence, related to Tamil refugees in 1985 and her meeting with Nelson Mandela in 1990, to show that Mrs. Thatcher was indeed a freedom sniper and not a ‘freedom fighter’.

Mandela on Thatcher

In his book, Conversations with Myself (2011), Mandela had reminisced his meeting with Thatcher as follows: (dots, words within parenthesis and in italics, are as in the original)

“I met [with] Mrs. Thatcher…for…close to three hours, and naturally we discussed the question of sanctions and the general political situation in South Africa. She was interested in our relations with [Mangosuthu] Buthelezi…I made no impression whatsoever on the questions of sanctions…[I said] to her that ‘We are an oppressed community and we need to do something…to put pressure on the regime to change its policies, and the only pressure of a formidable nature that we could exert is that of sanctions.’ I couldn’t make any impression. But she was charming and then I had a private lunch with her.” (p. 385)

Then, we have this observation from Richard Dowden (the director of the Royal African Society), which appeared in the Guardian (London) daily on April 10, 2013.

“My last meeting with Thatcher was at De Klerk’s book launch at Foyles in 1999. I asked her about South Africa and her role. She launched into praise for De Klerk and then for Van der Post and Buthelezi – ‘a marvellous man’ she kept repeating. I asked what she thought about Mandela. ‘I never met him,’ she said looking confused. How could anyone meet Mandela and not remember? Now I realise why.”

“My last meeting with Thatcher was at De Klerk’s book launch at Foyles in 1999. I asked her about South Africa and her role. She launched into praise for De Klerk and then for Van der Post and Buthelezi – ‘a marvellous man’ she kept repeating. I asked what she thought about Mandela. ‘I never met him,’ she said looking confused. How could anyone meet Mandela and not remember? Now I realise why.”

This episode presented by Richard Dowden indicates vividly that by 1999, Mrs. Thatcher’s dementia had ripened seriously.

My recent email correspondence with Lord David Owen

On April 13th, after I submitted my previous commentary on Thatcher to this website, I sent the following email to Lord David Owen, whose papers I had cited.

“Dear Lord Owen:

Greetings from Japan. Following the death of Margaret Thatcher, I read two of your papers on hubris syndrome, which were published in J. Royal Soc. of Medicine (2006) and Brain (2009). I enjoyed reading these papers, as you would have keenly observed her behavior in the British parliament.

In the Brain (2009) paper which you had co-authored with Jonathan Davidson, you mention that “Margaret Thatcher, we judge, did not develop hubris syndrome until 1988, 9 years after becoming Prime Minister. But some believe she was hubristic throughout her period in office.”

Considering the fact that she was diagnosed as suffering from dementia, during her retirement years, I wonder whether even during her prime ministerial term, she might have suffered from pre-senile dementia. Can one be certain on this issue? I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this. Best regards.”

I did receive Lord Owen’s response on April 19th. I paraphrase his reply. Lord Owen had mentioned that he doubts whether any cognition tests were carried out on Mrs Thatcher during her prime minister phase. In the absence of such tests, now a study is being framed to analyze her answers to the questions in the parliament during her prime minister phase with that of controls (her two successors).

I did receive Lord Owen’s response on April 19th. I paraphrase his reply. Lord Owen had mentioned that he doubts whether any cognition tests were carried out on Mrs Thatcher during her prime minister phase. In the absence of such tests, now a study is being framed to analyze her answers to the questions in the parliament during her prime minister phase with that of controls (her two successors).

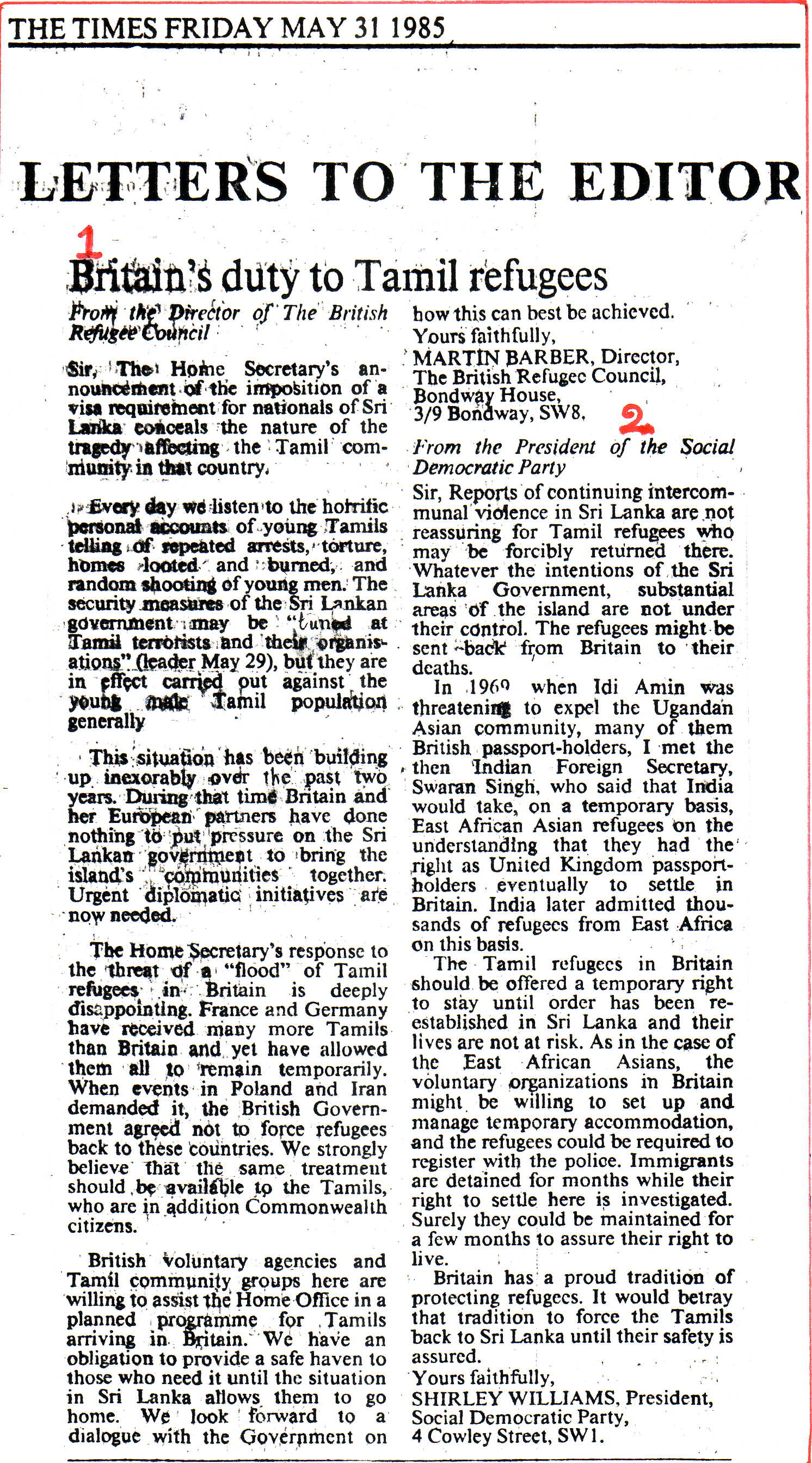

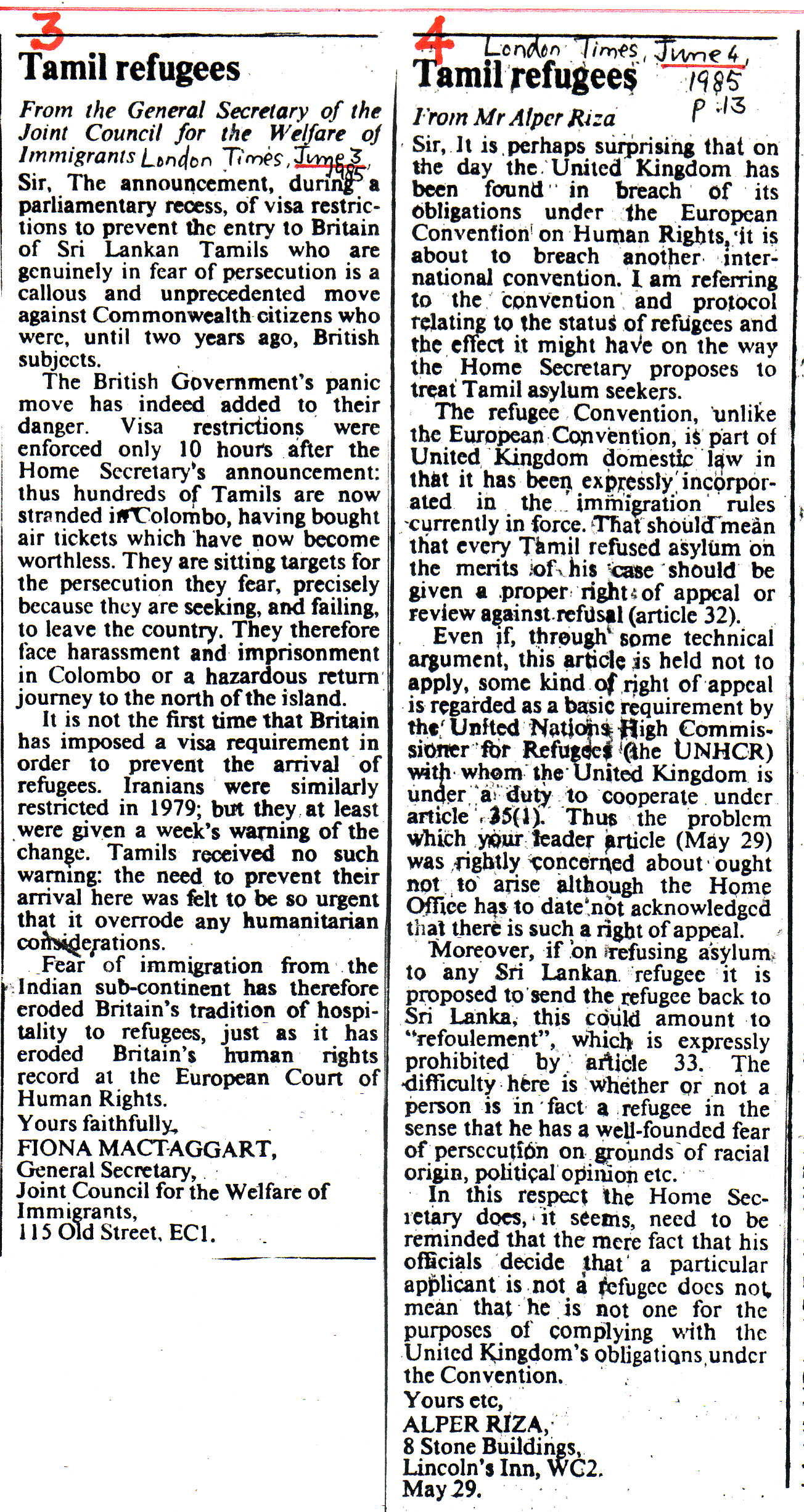

Letters on Tamil Refugees

For record, I provide the letters that appeared on the Eelam Tamil refugee issue, which was precipitated during Mrs. Thatcher’s prime minister period in 1985. As I indicated in my previous commentary, Thatcher’s then Home Secretary Leon Brittan announced a new rule for Sri Lankan Tamils who were fleeing to Britain from persecution, in less than 10 hours before it was due to come into effect. The Times (London) daily carried four letters in its columns on May 31, June 3, and June 4 of 1985. All these letters were from British nationals. I have somewhat smudged copies of these four letters, which I have transcribed below for clarity. (You should understand that I made copies of these letters from a prolifically used copier at the University of Illinois library, when I was a graduate student there.)

Britain’s duty to Tamil Refugees

[The Times, May 31, 1985]

Sir, The Home Secretary’s announcement of the imposition of a visa requirement for nationals of Sri Lanka conceals the nature of the tragedy affecting the Tamil community in that country.

Every day we listen to the horrific personal accounts of young Tamils telling of repeated arrests, torture, homes looted and burned, and random shooting of young men. The security measures of the Sri Lankan government may be ‘tuned at Tamil terrorists and their organisations’ (May 29), but they are in effect carried out against the young male Tamil population generally.

The situation has been building up inexorably over the past two years. During that time Britain and her European partners have done nothing to put pressure on the Sri Lankan government to bring the island’s communities together. Urgent diplomatic initiatives are now needed.

The Home Secretary’s response to the threat of a ‘flood’ of Tamil refugees in Britain is deeply disappointing. France and Germany have received many more Tamils than Britain and yet have allowed them all to remain temporarily. When events in Poland and Iran demanded it, the British Government agreed not to force refugees back to these countries. We strongly believe that the same treatment should be available to the Tamils, who are in addition Commonwealth citizens.

British voluntary agencies and Tamil community groups here are willing to assist the Home Office in a planned programme for Tamils arriving in Britain. We have an obligation to provide a safe haven to those who need it until the situation in Sri Lanka allows them to go home. We look forward to a dialogue with the Government on how this can best be achieved.

Martin Barber,

Director, The British Refugee Council.

Sir, Reports of continuing intercommunal violence in Sri Lanka are not reassuring for Tamil refugees who may be forcibly returned there. Whatever the intentions of the Sri Lanka government, substantial areas of the island are not under their control. The refugees might be sent back from Britain to their deaths.

In 1969 when Idi Amin was threatening to expel the Ugandan Asian community, many of them British passport-holders, I met the then Indian Foreign Secretary, Swaran Singh, who said that India would take, on a temporary basis, East African Asian refugees on the understanding that they had the right as United Kingdom passport-holders eventually to settle in Britain. India later admitted thousands of refugees from East Africa on this basis.

The Tamil refugees in Britain should be offered a temporary right to stay until order has been reestablished in Sri Lanka and their lives are not at risk. As in the case of the East African Asians, the voluntary organizations in Britain might be willing to set up and manage temporary accommodation, and the refugees could be required to register with the police. Immigrants are detained for months while their right to settle here is investigated. Surely they could be maintained for a few months to assure their right to live.

Britain has a proud tradition of protecting refugees. It would betray that tradition to force the Tamils back to Sri Lanka until their safety is assured.

Shirley Williams,

President, Social Democratic Party

Tamil Refugees

[The Times, June 3, 1985]

Sir, The announcement, during a parliamentary recess, of visa restrictions to prevent the entry to Britain of Sri Lankan Tamils who are genuinely in fear of persecution is a callous and unprecedented move against Commonwealth citizens who were, until two years ago, British subjects.

The British Government’s panic move has indeed added to their danger. Visa restrictions were enforced only 10 hours after the Home Secretary’s announcement: thus hundreds of Tamils are now stranded in Colombo, having bought air tickets which have now become worthless. They are sitting targets for the persecution they fear, precisely because they are seeking, and failing, to leave the country. They therefore face harassment and imprisonment in Colombo or a hazardous return journey to the north of the island.

It is not the first time that Britain has imposed a visa requirement in order to prevent the arrival of refugees. Iranians were similarly restricted in 1979; but they at least were given a week’s warning of the change. Tamils received no such warning; the need to prevent their arrival here was felt to be so urgent that it overrode any humanitarian considerations.

Fear of immigration from the Indian subcontinent has therefore eroded Britain’s tradition of hospitality to refugees, just as it has eroded Britain’s human rights record at the European Court of Human Rights.

Fiona Mactaggart,

General Secretary, Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants.

Letter 4

Tamil Refugees

[The Times, June 4, 1985]

Sir, It is perhaps surprising that on the day the United Kingdom has been found in breach of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights, it is about to breach another international convention. I am referring to the convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees and the effect it might have on the way the Home Secretary proposes to treat Tamil asylum seekers.

The refugee Convention, unlike the European Convention, is part of United Kingdom domestic law in that it has been expressly incorporated in the immigration rules currently in force. That should mean that every Tamil refused asylum on the merits of his case should be given a proper right of appeal or review against refusal (article 32).

Even if, through some technical argument, this article is held not to apply, some kind of right of appeal is regarded as a basic requirement by the United Nations High Commisssioner for Refugees (the UNHCR) with whom the United Kingdom is under a duty to cooperate under article 35(1). Thus the problem which your leader article (May 29) was rightly concerned about ought not to arise although the Home Office has to date not acknowledged that there is such a right of appeal.

Moreover, if on refusing asylum to any Sri Lankan refugee it is proposed to send the refugee back to Sri Lanka, this could amount to ‘refoulement’, which is expressly prohibited by article 33. The difficulty here is whether or not a person is in fact a refugee in the sense that he has a well-founded fear of persecution on grounds of racial origin, political opinion etc.

In this respect the Home Secretary does, it seems, need to be reminded that the mere fact that his officials decide that a particular applicant is not a refugee does not mean that he is not one for the purposes of complying with the United Kingdom’s obligations under the Convention.

Alper Riza,

Lincoln’s Inn, London WC2.