by Sivananthiram Alagandram, Geneva, January 6, 2023

This is the story of Jaffna Tamils who came to Port Swettenham at the turn of the 20th century and virtually ran the port and railways in the town. They arrived in Port Swettenham at the invitation of the British to develop the port and manage the Railways. The port, which opened in 1901, exported rubber and tin to North America and Europe.Location of Port Klang, Malaysia

Equipped with English, technical and administrative skills, and with no capital which they brought with them, Jaffna Tamils helped to make Port Swettenham the fastest growing port in the country and in the process entrenched themselves as middle-class citizens within a short span of time. They were the backbone and unchallenged leaders of the British administration in the port town. Above all, they observed cultural norms from Jaffna and they never lost their distinct communal identity. Today, Port Swettenham, which has been renamed Port Klang, has become a world-class port thanks to the contributions of Jaffna Tamils and the managerial skills of port managers, Rajasingam and Ghanalingam, both sons of Jaffna Tamil immigrants in Malaysia.

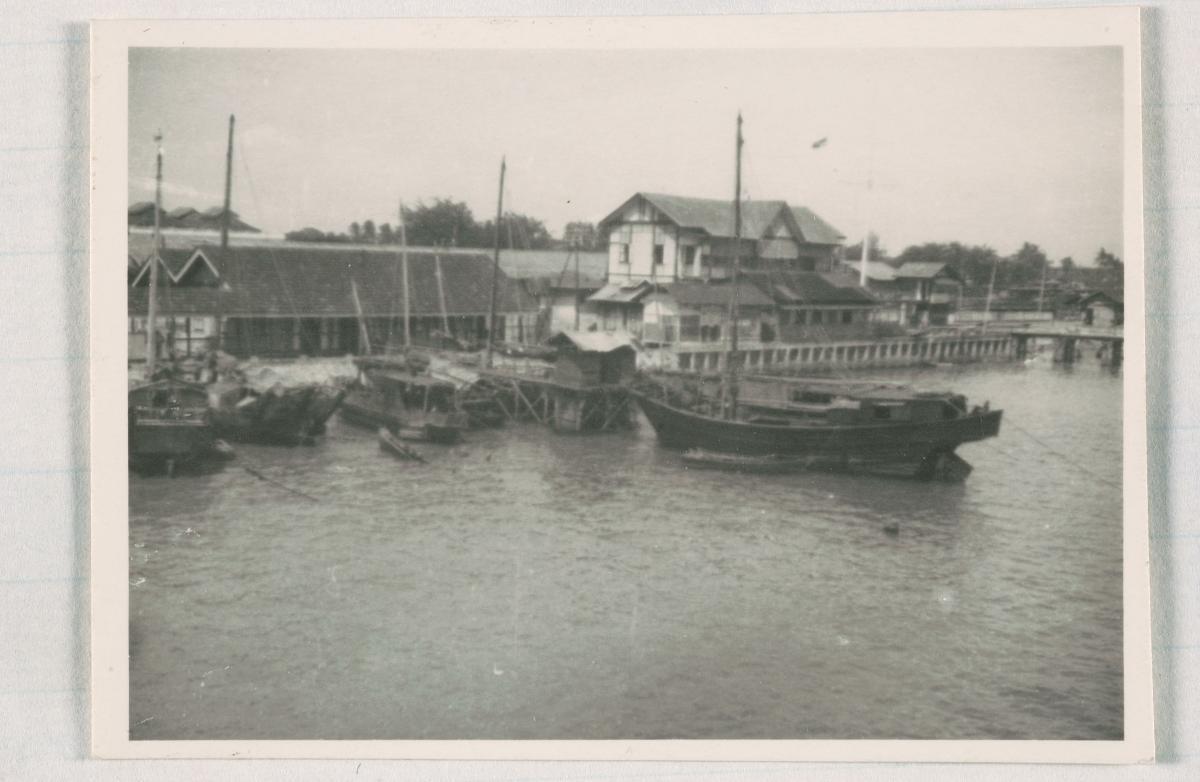

The Harbour Master’s Office and the Port Swettenham’s Railway Yard

The classic divide-and-rule policy used by the British since the middle of the 18th Century drained the economic wealth of many of their colonies resulting in their underdevelopment. In Malaya, working closely with large European commercial capitalist companies which included Barlow Bousted, Harrison & Crossfield, Lever Brothers, Socfin, United Plantations, Dunlops, Guthries, Tronoh Mines, Southern Malayan Tin Dredging company, etc, the British reaped one of the highest returns on investments in the world which was all repatriated to Europe. At the turn of the 20th century, British Malaya was one of the highest recipients of British foreign investments, mostly in rubber and tin, and was the fastest-growing economy in South East Asia. The British colonial government deliberately skewed the economy to be dependent as an exporter of raw materials without efforts to industrialize the economy, thus making Malaya very reliant of British-made goods, resulting in the terms of trade in favor of London.

The Port Swettenham Railway Station. It is the oldest railway line existing today in Malaysia. In the 1950’s,Sinnathamby Station Master’s commendable and excellent work contributed to rapid rise of Port Swettenham as the leading port in Malaya.

For the Malayan economy to develop, the colonial government invested a huge amount of funds to build one of the best systems of railways and roads to serve the needs of their European investors. To ensure efficient exploitation of natural recourses, they needed an efficient low cost and capable administration for the civil service, plantations, and mines and looked to Jaffna as a favored destination to provide the clerical/technical and subordinate manpower.

In Jaffna, thanks to Mission Schools, there was a ready pool of English-educated manpower available. Some of the outputs from these schools were already recruited by the Ceylon Colonial Government and the Jaffna Tamils gained valuable experience in administrative and technical fields in their own country. Those who retired to their villages in Jaffna after working for the government in Ceylon had a better quality of life. With the reasonable pension they were receiving, they lived in comfortable brick houses and were able to command the respect of village elders and act as prominent personalities in the village.One of the big push factors that facilitated this process in Ceylon was the barrenness of legendary red Jaffna soil which was getting depleted. It was proving more and more difficult to make a living in the arid Jaffna Peninsula. This was a big factor in pushing many youths out of the traditional agricultural economy and into seeking English education for employment in the public sector in Sri Lanka and in the tea plantations in the upcountry.By the end of the 19th Century, the Ports of Singapore, Penang, and Malacca were under British control and they not only served as platforms for expansion into the Malay Peninsula but were also strategically located to protect the valuable trade route to China where the Europeans forced opium grown in India into China in return for tea. By now British Malaya was increasingly become an important producer of natural rubber and tin, exported mostly from Perak, Selangor Negeri Sembilan Pahang, and Johore. When it became more efficient to export rubber and tin by railway from Kuala Lumpur to Port Swettenham, vast investments in infrastructure were made by the British colonial government in particular for the building of roads and railway lines right up to Port Swettenham. This investment, together with development of an ocean-going port, became a reality due to the lobbying efforts of the European plantation interests and foreign mining corporations. Before the Railway connection to Port Swettenham came into being, the only methods of transportation to the port near the mouth of the Klang River were horse- and buffalo-drawn wagons or by boat through the Klang River.Railway lines and roads led to the remarkable development of Port Swettenham. Rubber and tin from Ipoh in the tin state of Perak in the north to Malacca in the south began to be exported in large quantities very quickly through Port Swettenham to avoid the need to transport them to Penang and Singapore which was more expensive. These changes created further demand for middle-level clerical /technical positions for both direct employment with the Harbour Masters Office and the Malayan Railways and also indirect employment in operational activities such as cargo handling, shipping, and forwarding where agencies like Bousted Shipping Agencies and Harper Gilfillan group monopolized the shipping trade.

Prior to the Second World War, higher-level civil service posts were open to European officers only, who were recruited into Malayan Civil Service after passing an exam. Middle-level and lower-level posts in technical, clerical, teaching, and medical work were open to Asians. In 1920, when my grandfather, Ayadurai Sinnathambar landed at the Port Swettenham Pier, employment at the port and railways was more or less monopolized by Ceylon Tamils occupying the majority of lower-level appointments from railway clerks to the station masters, the positions in the port just below the Europeans.During the first few decades of the 20th century, the early Jaffna migrants played a crucial role in developing the port and the infrastructure, which included surveying, and building roads and railway lines in areas that were jungle where the local Malays were reluctant to work. Most of the Jaffna Tamil pioneers who landed like my grandfather in Port Swettenham were employed as subordinate officials to provide middle-level clerical and technical support for the harbor masters office, Port Swettenham railway station, office of the customs department, marine office, police station, the warehouses, wharves, the government quarters, quarantine camp and coolie depot. etc Work and life were not easy and some succumbed to Malaria which plagued this port town in its early years.

The status the Jaffna immigrants enjoyed was largely determined by the positions they held, their salary, their promotional prospects, and the pension they were entitled to. They treasured their relationship with their British masters in order to retain their positions and move up the occupational ladder. Their British masters too became more and more dependent on them. Many of the chief clerks and Office Assistants wielded much influence which enabled them to secure jobs for their friends and relatives from the same neighborhood in Jaffna.Prior to WW2, in the two-level Malayan Civil Service, Jaffna Tamils could not be promoted to the senior services however qualified. Experienced railway inspectors and station masters, who had knowledge of both goods and coaching work, and surveyors were paid between $80 to $100 per month depending on their experience. Their role as junior officials involved in maintaining and laying of railway lines and ensuring the smooth running of trains including goods imported and exported out of the port cannot be underrated.My grandfather, who was recruited as a clerk to work in the port’s claims department. was paid a monthly salary of $50 a month. His contract stipulated the payment of half his salary on embarkation in Jaffna, he was provided with unfurnished quarters on arrival and he was assured a free second-class passage from Jaffna. Likewise, road overseers who constructed and maintained roads were paid from $25-30 for their ability to keep check rolls and distribution sheets, and for having some knowledge of road construction.Jaffna Tamils played a significant role in Port Swettenham’s support services such as postal, customs, electrical, teaching, and medical services. In the railways, successive station masters were Jaffna Tamils. The was also the case with the post office.There was a wide gap in conditions of employment when compared with the salary and perks enjoyed by European officials and Eurasians. Although the wages of Jaffna Tamils were much above the living wage, the pay was not commensurate with the productivity of the Jaffna Tamils who were known for their hard and smart work. The wages paid were also not in keeping with the growth of the economy which was growing at about 2.9% annually before WW2. However, as a migrant community, they were a fortunate group compared to many migrants in other countries. By securing relatively permanent jobs in Port Swettenham with the civil service and private sector, they enjoyed the security of employment and a relatively good quality of life made possible by economic growth in Malaya which also ensured steady growth of their household incomes except for a short period during the Great Depression of the early 1930s.The Jaffna Tamils were a thrifty community and with the arrival of their womenfolk, they lived a frugal life so that the maximum amount of money could be sent back to Jaffna to support family members they left behind. It is also true to say that remittances from Malaya were responsible for the relative prosperity of Jaffna during this period.By the 1920s, Port Swettenham had become the most important sea gateway in Peninsular Malaya and emerged as one of the fastest-growing towns in the country with road and railway links to all parts of Malaya and an ocean port reaching all parts of the world. This port town was well equipped with a post office, immigration office, customs office, police station, railway station, bus stand, a dispensary, and a quarantine deport all to service the port and mostly manned by Jaffna Tamils. The colonial government put in place a good network of roads stretching from the port to Klang and Kuala Lumpur and in addition, they built good roads in the town itself along Padang Road, Camp Road, Dock Road, Barrowman Road, Hort Road, and the infamous Samy Road.The government quarters stretched all along most of these roads with higher-level officials housed at single-story bungalows, and semi-detached houses. The Jaffna Tamils holding clerical/technical positions were housed in terraced wooden houses along Padang Road and the road leading to the quarantine depot and meeting the newer “cement quarters ” built behind the Mariner’s Club.My grandfather was allocated a terraced wooden house in a row built on brick pillars along Padang Road. These quarters were built above the ground level due to heavy rains that can cause floods. This house had a small verandah and a living room with two adjourning rooms. There were steps leading to the kitchen, bathroom, and toilet. In front of our home in Padang Road was the town’s main football /cricket field which hosted the local football competition and where cricket matches were played by visiting marines and local youths.Among the many Jaffna Tamils who lived in our neighborhood were Station Master Sinnathamby, Cashier Vathilangam, Rajaratnam, Yard Master Ponnuddurai, Traffic Inspector Thambiah, Accountant Kanavathipllai, loco Kandiah, Eliathamby, Selvaratnam, Maniam, Krishnapillay all from Railways, , Chelliah and Singaratnam from Harbour Master’s Office, Post Masters Ratnam and Chellathurai, Veterinary Officer Ponnudurai, Muthukumarasamy, Selvaratnam, and Singaratnam from customs, Ehambaram, Kitchy Murugesu from the port, health Inspector Markandu, and many others working in Port Swettenham. During this golden era between the 1930s to 1950s, Jaffna Tamils made up at least 60% of those residing in government houses. Their institutional memory and sound knowledge of administrative matters gave them great influence in their respective places of employment. Some of them like Muthukumarasamy were awarded MBE and others meritorious service medals in recognition of their excellent service to the Crown.Many Jaffna Tamils commuted from Klang daily to the port. Among them was Seenithamby who was employed with Bousted Shipping Agencies and Gunaratnam with the Harper Gilfillan company. Every Jaffna parent in Port Swettenham made sure that their children attended one of the English schools in Klang such as the Convent, High School, Anglo-Chinese School, and Methodist Girl’s School.By this time, the Jaffna Tamils in Port Klang had emerged as a cohesive Community. The Government quarters where they resided were all concentrated in a small area which facilitated easy communication at a time when telephones existed in very few homes. As a community, they were proud of their Jaffna heritage. For the Jaffna Tamils, learning of Tamil language was considered a priority to better understand and preserve Tamil culture. They organized the Town Tamil School for Tamil education for their children. This school was run by a Japanese Board of Governors and in the 1950’s Muthukumarasamy served on its board and ensured that the Tamil education provided here was one of high quality. The arrival of Tamil teachers from Jaffna namely Subramaniam, Sockalingam Ponnambalams, and Somasundrams enhanced the status of the school in providing quality Tamil education for the children of Jaffna Tamils.The Jaffna Tamils in Port Swettenham supported the construction of the Subramania Swami Temple on Telok Pulai Road. This temple they frequented continues to preserve its Hindu heritage from Jaffna. From its very early years, the temple administration was in the hands of an educated Jaffna middle-class community many of whom were from Port Swettenham which ensured that the temple could be run along the lines of the Nallur temple in Jaffna. . Many Jaffna Tamils from Port Swettenham would attend the Friday prayers in the evenings where they would, pray, speak in their own dialect to their own countrymen and discuss developments in Jaffna.The community participated actively in the annual Chitra Paurnami celebrations organized by the Bala Subramania Temple in Dock Road during the month of April. They would erect Thaneer Pandals in front of the Government quarters for the devotees carrying Kavaddis. Likewise, they participated actively in the annual Navaratri celebrations and the annual school concert organized by the Town Tamil School which was held towards the end of the festival.In 1953, when I was schooling in this Tamil school, the concerts were professionally conducted by teacher Ponnambalam and his learned wife. It was a memorable event where the Tamil school students would sing, dance, and act in plays based on stories from the holy scriptures. They would often invite prominent personalities to grace the event. In the early 1950s, they invited Kandiah, the father of famous Australian singer Kamal to perform at this event. Kandiah was an active member of the Sangeetha Abivirthi Sabha and the melodious songs he sang reminded the audience of their past years at school in Jaffna, their cultural characteristics, and their distinct identity.Tan Sri Ramond Navaratnam

The earliest English language school established in Port Swettenham was by the Jaffna Tamil Protestant mission. This enabled some of the children of the early pioneers in Port Swettenham to acquire an English education. The Headmaster of this Methodist School was Thalyasingam whose nephew was Tan Sri Ramond Navaratnam who later became the Secretary General of the Ministry of Transport.

With their children growing up in this country more and more Jaffna Tamils showed little interest in going back to Jaffna. The benefits of a better quality of life in terms of health, education, and urban lifestyle clearly out weighted the thoughts of returning home. After retirement, many of the Jaffna Tamils like my grandfather made Klang their home, particularly on Telok Pulai road near the Subramanya temple. Many others made their home in the 32 houses built by the Jaffna Tamil Cooperative Housing Society, opposite the Perumal Temple along Telok Gadong road. These included Muthukumarasamy, Hospital Assistant Saranvanamuthu, Station Master Sinnathamby, and many others.The Jaffna Tamils landed in Port Swettenham as birds of passage hoping to go back to their villages on retirement. They spent about 30- 35 years working for the port and railways so as to economically uplift themselves and support those they left behind. They were the pillars on which Port Swettenham grew. They came with little funds and depended entirely on the colonial government and its private sector. The Colonial Administration highly respected the community’s diligence and loyalty. It was their hard work, and good knowledge of the English language, combined with the trustworthiness that enabled them to establish themselves as a permanent middle-class community within a span of about 50 years, something no other community was able to accomplish. As a minority in the country, they posed no threat to the British. Seen as cooperative workers, the colonial system gave them social power within the system which gave them the self-confidence they needed to work in a foreign country. All in all, they were unchallenged leaders of the bureaucracy in Port Swettenham.It is true to say that in the 1920s they not only ran the railways but the port itself. As a community in the port town, they stood apart from other communities in terms of their status, communal spirit, and distinctiveness. Their children and grandchildren though localized were groomed to maintain the distinct Jaffna cultural distinctiveness. Building on the solid foundation provided by the pioneers from Port Swettenham, many of them today are doctors lawyers, engineers, and consultants. They have carried on with the same determination and drive and have positioned themselves in the country as upper-middle-class citizens. Whilst the early pioneers built the railways and ports, it was also the contributions of two Jaffna Tamils, Rajasingam and Ghanalingam which allowed Port Klang to turn into a world class port with trade connections with over 120 countries and a network with over 500 ports all around the world.