– But are war criminals being let in?

by Tamil Guardian, London, August 2, 2021

.png)

The United States says that all Sri Lankan soldiers continue to be fully vetted for involvement in human rights abuses before being allowed to train in the country. Recent appointments however point to holes in the vetting process and raise questions from survivors.

Dr Varatharajah can still remember the constant humming of the Sri Lankan military aircraft flying overhead.

“It was right above us,” he says. “But if you looked at the sky, all you could see was a tiny dot.” He was in the midst of tending to victims at a hospital in Puthukkudiyiruppu, in February 2009. The building had been clearly marked with a massive red cross painted on the roof and its GPS coordinates repeatedly sent to the Sri Lankan military. The aircraft overhead was not a fighter jet, but a surveillance flight scoping out the military’s next target.

That week, under the watch of the surveillance aircraft, the hospital came under almost constant aerial attack, says Dr Varatharajah. Hundreds were killed and tens of thousands more would be massacred in the weeks that followed.

More than 12 years later, the US Ambassador to Sri Lanka announced that a Sri Lankan soldier who reportedly flew those surveillance missions would be joining the US Air Command and Staff College in Montgomery, Alabama. “Welcome aboard Wing Commander Mutaliph!” tweeted Alaina Teplitz last month. The US Embassy in Colombo posted a photograph of the soldier outside the college, hands on hips and in full military uniform.

For many, the image of yet another Sri Lankan soldier training at an American military institution will not be a new one. Throughout the armed conflict on the island, the US provided both diplomatic and military assistance to the Sri Lankan state. The training of Ershad Mutaliph however, who claims to have piloted military aircraft as the armed forces bombed hospitals and killed tens of thousands of Tamils, comes amidst a ramping up of militarisation and human rights abuses on the island, and closer global scrutiny over the US-Sri Lanka relationship. For many Tamils and human rights defenders around the world, including survivors such as Dr Varatharajah, there are serious questions to be answered.

‘Hundred percent spot-on’

.jpg)

Raytheon Beechcraft with distinctive underbelly radome

As per Mutaliph’s LinkedIn profile, he joined the Sri Lankan air force in 2004, before working his way up the ranks in the years that followed. As he joined, the Sri Lankan military underwent a period of massive growth and expansion. Whilst ill-fated peace talks with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were supposedly underway, the newly appointed Sri Lanka defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa was leading a huge recruitment drive, with numbers entering the armed forces rapidly expanding, a defence spending spree and a host of deadly new military hardware being purchased. Preparation for a massive military offensive was well underway.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Ershad Mutaliph’s Sri Lankan air force career, as per his LinkedIn profile.

As Sri Lankan forces launched their attacks, Mutaliph states he was swiftly promoted from commissioned officer to operational pilot on Y-12 and Beechcraft B200 aircraft. Though the planes themselves were not bomber jets, they played a crucial role. The US-based defense conglomerate Raytheon reportedly supplied the Beechcraft to Sri Lanka in 2002, and was said to be equipped with a Hughes synthetic aperture radar system. Since then the Beechcraft would routinely patrol the skies of the North-East, earning itself the apt local nickname ‘Vandu’ – bug or beetle in Tamil.

Sri Lanka’s Air Force Commander, Air Chief Marshal Gunatillake, would later tell a government commission of the vital surveillance and reconnaissance work that aircraft such as the Beechcraft, alongside drones and other unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), would undertake. “Initially we get a lot of intelligence,” he said.

“We send our UAVs or the Beechcraft… we try to find out if there are civilian places… or anything else that might get damaged if we take the target from the air. Once we are satisfied with all of this, we send the pictures to the attack squadrons that we detail to take the target, we match our weapons according to the target.”

“In every instance we have been hundred percent spot-on,” he concluded.

‘The bombings were relentless’

In the midst of the massacres in 2009, the military publically showcased the level of detailed surveillance that these aircraft were able to carry out. Whilst Gotabaya Rajapaksa was attempting to justify the shelling of hospitals, the Sri Lankan air force took a different tact, inviting international journalists to see its operations and releasing a video from a Beechcraft plane – the same type of aircraft that Mutaliph claims to have piloted at the time.

The surveillance footage, which the military claims was taken on February 6th, shows PTK hospital – the same facility that Dr Varatharajah was treating patients in – apparently untouched.

A Sri Lankan airforce video reportedly taken from a Beechcraft plane.

The video is remarkably detailed. The numerous red crosses painted on the hospital building roofs are seen, as well as parked ambulances and other vehicles. Strangely, there seems to be no activity at the hospital at all. “The video footage clearly shows the buildings of the former Puthukudduyiruppu hospital with no damages caused due to artillery fire or aerial bombardment,” claimed a post by Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Defence, adding that UN officials had been “ill informed”.

The United Nations, satellite imagery, witness testimony and the rapidly rising death toll, however, prove otherwise.

“PTK hospital was one of the most heavily hit medical facilities,” reads the UN OHCHR investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), stating that the hospital and the United Nations facility “were subjected to significant bombardments between 10 January and 6 February 2009”. It goes on to describe the many repeated bombings of the hospital, including several times when the hospital was directly hit and hundreds of casualties caused.

“One hospital worker described the situation in the hospital by 4 February as “carnage”, the likes of which she had never seen before,” the OISL continues. “Medical staff members were struggling to provide care to hundreds of injured patients, who continued to arrive, with medical infrastructure in ruins, and hospital personnel forced to hide in bunkers due to the ongoing shelling.”

“The bombings were relentless,” recalls Dr Varatharajah. “I do not know exactly which surveillance aircraft was overhead, but there was almost a 24-hour presence above the hospital.”

He says the attacks leading up to February 4 were amongst the most intense, with wards shelled and an “impossible” operating environment. He can still remember the colleagues who were injured and civilians killed. All the staff at the hospital were forced to flee.

Dr Varatharajah providing a video update at a makeshift hospital, 2009.

Tens of thousands were killed by Sri Lankan shells in the weeks to come. The doctor, who fled the island in the aftermath of the massacres, still struggles with the memories of the time.

The Sri Lankan state however, revelled in its devastating military victory. Mutaliph’s profile states he was made a Captain in the air force in May 2009 – the deadliest month in the island’s history of armed conflict. Mullaitivu, the district that suffered the heaviest bombardments and home to what has since been dubbed ‘Sri Lanka’s killing fields’, remains under military occupation. In the years that followed, Gotabaya Rajapaksa promoted Mutaliph to Temporary Squadron Leader in 2014. Since then, Rajapaksa has been appointed as Sri Lanka’s president and has increasingly appointed other senior military officials accused of rights abuses into powerful government roles.

To date, no military or political leader, has been held accountable for the massacres.

‘A serious obligation’

It is that lack of accountability that has raised particular concerns with regards to Mutaliph’s training.

.jpg)

US officials with a Sri Lankan recruit last month.

The Wing Commander’s enrolment at the US military college, is just the latest in a series of appointments, demonstrating the close-knit training ties with Sri Lanka. Last month, Teplitz tweeted her congratulations to a Sri Lankan police officer who was to serve as a Deputy Director in the Criminal Investigation Department and had completed a course at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Hawaii.

Earlier this month, the US ambassador once more tweeted her congratulations to another Sri Lanka recruit who will be starting at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado. “Another fine example of the strong defense partnership between our two nations,” she added.

And just last week, the US added that another Sri Lankan air force captain would be joining the US military college.

“Since 1970, over 1,500 Sri Lankan personnel have received training at Department of Defense locations in the United States,” the US Embassy in Colombo told the Tamil Guardian. It remains unclear how many Sri Lankan personnel have been complicit in human rights abuses, either before or after receiving US training.

“The Sri Lankan Air Force has been notorious since the 80’s for deliberately killing Tamil civilians, in what could be reasonably considered a campaign of genocide,” said Together Against Genocide (TAG) director Jan Jananayagam, pointing to infamous massacres such as the bombing of Nagerkovil and Sencholai schools. “Yet through it all Sri Lanka’s air force has received international assistance and training that only serves to make them more effective killers of Tamil civilians.”

However, the US still states it continues to vet Sri Lankan military personnel.

“The United States manages its security relationship with the Government of Sri Lanka in the context of our concern for human rights and the rule of law,” the US embassy said, citing the Leahy amendment, which prohibits the state from providing security assistance or training “to a security force unit or individual when we have credible information that the unit or person has committed gross violations of human rights until the host nation government takes effective steps to bring those responsible to justice”.

“This is a serious obligation, and we fully apply the Leahy law when providing security assistance, including the training of individuals,” the US continued.

The US embassy went on to state,

“Wing Commander Ershad Mutaliph’s attendance at the U.S. Air Force Command and Staff College was vetted in complete accordance with Leahy requirements.”

US vetting of Sri Lankan soldiers

Leahy vetting is currently carried out by the US State Department, which “evaluates and assesses available information about the human rights records of the unit and the individual, reviewing a full spectrum of open source and classified records, including international records,” according to the embassy.

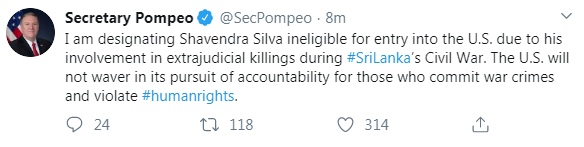

There have been examples of that vetting process being carried out with regards to the USA’s military engagement with Sri Lanka. That same type of procedure would have led to the barring of the head of Sri Lanka’s army, General Shavendra Silva, from entry to the USA last year.

The head of Sri Lanka’s army, Shavendra Silva

A statement released by then-US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that Silva and his immediate family are now “are ineligible for entry into the United States” due to “credible information of his involvement, through command responsibility, in gross violations of human rights”. “The allegations of gross human rights violations against Shavendra Silva, documented by the United Nations and other organizations, are serious and credible,” Pompeo added at the time.

In January 2013, there were also reports that Sri Lanka’s Major General Sudantha Ranasinghe was refused entry into the US for military training, with speculation that it may be on grounds that he is suspected of overseeing human rights violations. Later that year in August, Ranasinghe was reported to have also been rejected from a US-led training program in New Zealand, with the US Embassy in Colombo citing “credible allegations” of human rights violations. At the time Ranasinghe had been appointed General Officer Commanding of the Army’s 53 Division. At the time a US Embassy official had said, “there is a cloud over certain divisions because of the allegations”. “The important thing is the way forward and that path is clear – a credible investigation to clear the officials and units that may be implicated,” the official added.

Yet, there have also been several instances of Sri Lankan officials implicated in mass atrocities being able to freely travel to and from the United States. Until his presidential election bid, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, had obtained dual US citizenship, apparently only relinquishing it to contest in the island’s polls in 2019. Earlier this year, Basil Rajapaksa, yet another member of the Rajapaksa clan, also flew to the USA where he reportedly spent a month receiving medical treatment. On his return, he was sworn in as Sri Lanka’s Minister of Finance and continues to hold US citizenship.

.jpg)

The Rajapaksa siblings earleir this month.

One of the most telling images that demonstrates the duplicity that many feel over the US position, however, is that of Teplitz alongside Ranasinghe last year. Despite the Sri Lankan soldier having been twice rejected for US military training, the American ambassador was photographed handing over a shipment of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and having a discussion over tea and biscuits.

Teplitz with Ranasinghe, the Sri Lankan soldier who was barred from particiapting in a US military training program, in 2020.

“It is hard to see the present vetting process as anything other than a fig leaf for circumventing international rule of law including the Leahy amendment,” said Jananayagam.

“Given that the Sri Lankan authorities will hardly self-disclose their war crimes, vetting largely relies on perpetrators being publicly identified by international charities (such as human rights NGOs), even the largest of whom have no resources allocated for the task of identifying thousands upon thousands of war criminals on the island. Indeed, most of the handful of international NGOs working on Sri Lanka are volunteer-staffed micro-entities.”

Later this year, the issue of identifying and punishing perpetrators of war crimes will come under the international spotlight once more, as the United Nations Human Rights Council meets for its 48th session in September. Though numerous resolutions have criticised the lack of accountability for wartime abuses on the island, the current regime is more fervent than those before it in protecting perpetrators. Since coming into power Sri Lanka’s president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who himself stands accused of genocide, has pardoned perpetrators of crimes and even promoted accused war criminals to senior government and military positions.

Yet, Sri Lanka’s military relations with countries that have been seemingly vocal on justice and human rights, such as the United States, seem to continue unhindered.

“With Sri Lanka’s domestic institutions being complicit with its military apparatus, the burden has been pushed on to survivors to continue to speak out and to identify perpetrators, at huge cost and risk to themselves,” continued Jananayagam. “This is unacceptable.”

Tamil survivors, both in the Tamil homeland and scattered across the world such as Dr Varatharajah, feel the same. Their struggle for justice continues.