by T. Sabaratnam, August 20, 2004

Chapter 11

Original index to series

Original Chapter 12

The Training

In September, 1983 Chennai was full of Sri Lankan Tamil boys. They were taken to Delhi in batches in luxury buses by RAW officers.

“It was a tiring, long journey,” Nirupan (not his real name), a youth from my village, Ariyalai in Jaffna, told me when I met him a few years ago. He went for training with TELO’s first batch and is now living in Europe. TELO was the first group trained by India.

The bus covered the 2,000 kilometer journey in three days, he said. Their request to drive around Delhi was granted.

“We were taken sightseeing, but was not allowed to talk to anyone,” Nirupan said. From Delhi the group was taken to the training camp. They were told that that was a top secret project.

“We came to know that we were trained at Dehra Dun only when we returned to Chennai after finishing the three and a half month training. During that period we were not allowed to go out of the camp.”

The camp was on a mountain slope amidst a dense forest, fully hidden from the inquisitive, prying world.

“It was a nice place. We enjoyed our stay there. The only problem was the weather,” Nirupan said.

Nirupan recalled that he started shivering on the first night despite wrapping himself with the heavy blanket supplied to him. Each trainee was supplied with two quilts, an overcoat and foldable bedding when they were registered on entering the camp. “It was biting cold,” Nirupan said. He added that they got over the cold within a week.

“We got used to it,” he said. But they could not adjust themselves to the north Indian food. They were served chapathi, nan, puri with dhal, potato, egg or mutton curry. Occasionally they were served chicken. Rice and fish were rarities.

“The food was tasteless, no chillie at all,” was Nirupan’s complaint. “All of us longed for something hot and tasty,” he added.

TELO was the largest group. It sent 350 boys. The other groups that joined the training in the next few weeks were comparatively smaller. EROS sent 200 cadres, EPRLF 100, PLOTE 70 and the LTTE 50. Subsequently the groups sent further batches. The groups competed among themselves to derive the maximum benefit from the Indian training program.

Sri Sabaratnam led the TELO group, Balakumar the one from EROS, Douglas Devananda the EPRLF, Uma Maheswaran the PLOTE and Ponnamman alias Kuhan the LTTE. For Devananda and Uma Maheswaran it was refresher course as they had had their training in Lebanon.

Ponnamman alias Kuhan (photo courtesy www.tamilmaravan.com)

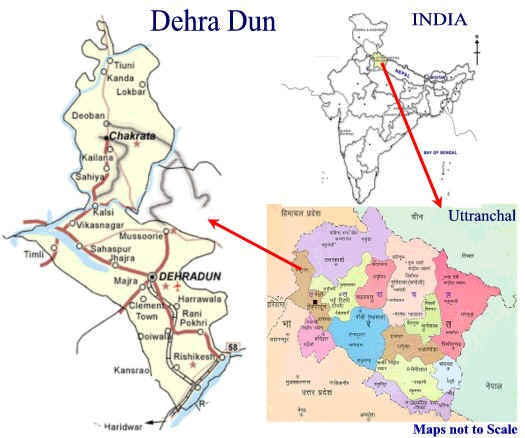

Training was given in three locations – Ramakrishnapuran in the heart of Delhi, a union territory, Dehra Dun, close to the Delhi airport and Chakrata, both in Uttar Pradesh. Each location had several camps.

Cadres from each group were housed separately and their general training was also separate. For specialized training cadres from the groups, except those from the LTTE, were brought together. The LTTE was kept separate altogether.

The Chakrata military complex in which LTTE cadres were trained was a top secret military training facility known in the intelligence circles as Establishment 22. It was set up jointly by RAW and the CIA to train Tibetan Kampas to subvert the Tibetan Chinese administration. Chakrata was allocated to the LTTE on the direction of Kao, in keeping with RAW’s undertaking to train the LTTE’s cadres at a separate camp.

As pointed out in the last chapter, Pirapaharan was reluctant to join the Indian training program because he realized that India’s purpose of training Tamil militants was different from the purpose for which they were fighting the Sri Lankan state. However, Pirapaharan was persuaded by Balasingham to accept the Indian training because the Indian training could be used by other militant groups to destroy the LTTE. Pirapaharan realized that, if that happened, the Tamil freedom struggle would be finished. So he decided to accept the Indian training.

Velupillai Balakumaran of EROS

The brochure titled, India and Eelam Tamil Crisis published by the LTTE in 1988-89 provides this information. The brochure says that Pirapaharan felt that India was determined to offer training to Tamil militants. He realized that, if he declined to accept the training, the other groups which were trained would be strengthened and they would use their newly gained strength to destroy the LTTE. That would be the end of the freedom struggle.

“We got the limited help. Anyhow on our own initiative, we set up a number of training camps and enhanced our military strength. Without depending on the Indian sources, we gathered substantial arms through our own resources,” the brochure added.

As this story develops we will give supporting material to show Pirapaharan’s thoughtfulness and the wise actions he took.

Pirapaharan asked RAW to train the LTTE cadres in a separate camp and RAW was happy about it. RAW had by then estimated that the LTTE was the best of the Tamil militant organizations. Pirapaharan took all possible precautions to prevent the LTTE being turned into its tool by RAW.

It is well known that the system of Iyakka Peyar (adopting an organizational name or alias) is common to all Tamil militant groups. That system was practiced for two purposes: to safeguard the family of the cadre from harassment and to bestow on the cadres a new identity. The new identity made the commitment of the cadres total. T he new identity helped the cadres to sever their connection with their past. Pirapaharan insisted that that practice be adopted religiously. Cadres were ordered to use the organizational names and told not to try to find out the real names of others or to dig for information about their families.

Pirapaharan instructed his cadres who went for Indian training to tell the RAW officers who registered them only their organizational names. That prevented RAW from knowing the actual identity of LTTE cadres. Ponnamman’s real identity was revealed only after his death. He died due to an accidental explosion in February 1987 at Navatkuli.

The Indian training schedule was rigourous. The day began at 8 a.m. with physical exercises. Breakfast was served at 9 a.m. Theory and practical classes were conducted in the morning, between 10 a.m. and 1 p.m. Theoretical knowledge about conventional and guerrilla warfare was imparted. Practical lessons were mainly about handling weapons.

Lunch was served between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m. The evening session was mainly on the firing ground. All cadres were taught to use Self Loading Rifles (SLR), A.K. 47, M 16, G 3, SMG, .303 revolvers, pistols, rocket launchers and the lobbing of grenades. Selected groups were given specialized and advanced training.

Specialized training included manufacture of explosives, manufacture and laying of land mines, handling of anti-tank weapons, communications and intelligence. A special TELO batch was trained to collect information on the movements of ships in Trincomalee harbour.

A member of that group told me that they were handpicked and given special instruction about ships, their identification by type and the countries to which they belonged. The group was taken to Bombay and trained by the Indian Navy to take photographs of the ships and to intercept radio messages and conversation. The necessary equipment were given to them. A core group was trained on underwater surveillance. Underwater diving was also taught.

That member told me that keeping the Trincomalee under constant watch seemed to be the priority concern of the Indian government. His trainers impressed on them that the Indian government was prepared to take all measures to prevent Trincomalee coming under the influence of America.

A group handpicked to do intelligence gathering were given five specific areas on which to focus their attention. They were:

- Military assistance from the US and Israel.

- Involvement of Keeny Meeny Services (KMS).

- Colombo’s relationship with Pakistan and China

- VOA

- Trincomalee harbour

Trainers were mostly army men who planned and assisted RAW operations in Bangladesh, Sikkim and Pakistan. Others were retired military instructors. Special instructors were assigned to each group and some of them continued their teaching assignments even after the militant groups shifted their training to the camps they established in Tamil Nadu.

Shankar Rajee and Douglas Devananda told me that some of the instructors were keen to collect information about Sri Lanka. They taught the trainees to prepare maps of roads, railways, bridges and other strategic installations. They said it was the responsibility of the trainees to supply them to India.

_112712023345.jpg)

Kittu

Instructors held periodic tests and rated the progress of the trainees. They gave marks for sincerity, good behaviour and accurate shooting.

The LTTE group won the affection of its instructors. A farewell function was held which turned emotional. The instructor who delivered the parting speech broke down with emotion. Kittu, who replied on behalf of the trainees, was equally moved. His words stuck in his throat. His eyes were wells of tear.

Ponamman reported this incident to Pirapaharan when they returned to Chennai. Pirapaharan fell silent for a moment. Then he said:

We joined the training with a certain objective. They (Indians) gave the training with a different objective. If their army is used, one day or other, against our objective, I will order Kittu to fight the Indian army. And Kittu would have to fight the Indian army.

Kittu recalled that incident when, four years later, Pirapaharan decided to fight the Indian army.

Shifting to Tamil Nadu

Pirapaharan shuttled between Madurai and Chennai after his Pondichcheri meeting. While in Chennai he stayed with Balasingham in their Santhome home, which was also used as the LTTE office. It was too crowded and impeded Balasingham’s work and posed considerable risk for Pirapaharan’s security. By the end of 1983 Balasingham and Adele moved to another house at Thiruvanmyur, an outer suburb of Chennai. Pirapaharan stayed with them when in Chennai.

They also rented another big house in Adayar and set up the LTTE’s political office. Balasingham and Adele established contact with the Indian and international media from the political office. The office also served as the meeting place where cadres who went to Chakrata for training called on Pirapaharan. Ponnamman, Kittu and Appaiah were among those who called. Appaiah was the oldest of them. He was in his late forties. He had already distinguished himself as a landmine expert.

In the last four months of 1983 Pirapaharan’s mind was focused on four matters, all of which affected his life, the history of the LTTE, the Tamil freedom struggle and the history of Sri Lanka. They were: the desire to derive maximum benefit from the Indian training program, the Batticaloa jail break, the role of women in the freedom struggle and his love affair.

Kittu in Tamil Nadu with politician Nedumaran

Pirapaharan ended up considering the Indian training offer a golden opportunity and decided to capitalize on it. He visualized building a conventional army making use of the knowledge Indian experts imparted on conventional warfare. As I mentioned earlier Santhosam, who was from my village, was in Chennai at that time and I asked him about the discussions they had during that time, particularly the matters that revealed the working of Pirapaharan’s mind.

Santhosam told me that Pirapaharan was definite about two matters: that the Indian training would be short-lived and India would keep the Tamil militant groups on a leash through its arms supplies.

India, Pirapaharan told his senior cadres, would stop training Tamil militants once their need to prop up Indian foreign policy ceased. Santhosam quoted Pirapaharan as saying, “When India’s foreign policy need ceases, India will not need us. If tomorrow J.R. dies and Sirimavo comes to power India will not need us.”

Pirapaharan also visualized another situation that would compel India to distance itself from Tamil militant groups. He said that, if international criticism mounted against training Tamil youths, India would backtrack. He ruled out the third possibility of J.R. adopting a conciliatory approach towards India’s concerns.

From these premises Pirapaharan drew two inferences. First, the LTTE should derive maximum benefit from the Indian training and support while it lasted. Second, they should build their own training and weapons capability.

These two inferences formed the bedrock of Pirapaharan’s policy and planning for the next four years. He decided to expand the LTTE’s training facilities in Vanni and Tamil Nadu. The LTTE was already running training camps in Vanni and Madurai. He commenced a program to strengthen those camps and build a new, vast network.

Simultaneously, Pirapaharan launched a program to build up his stock of weapons. “We will be India’s slaves as long as we depend on them for our weapons,” ever-smiling Santhosam recalled Pirapaharan telling. He started collecting an independent stockpile.

“Those are Pirapaharan’s wise decisions,” Ramesh Nadarajah once told me. And Nadarajah has written that clearly in his series “From Alfred Duraiappah to Gamimi,” which he wrote in Thinakathir from 1996 to 1999. He told me that he was facing severe criticism in his party, the Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP), for stating Pirapaharan’s strengths which made him a success. “I stated Pirapaharan’s strengths so that other militant organizations can learn from his success.”

Atputharajah Nadarajah, alias Ramesh

Pirapaharan stared expanding the training camps in Tamil Nadu while sending most of his senior cadres for training in Northern India. He sent about 200 of his men for training in Chakrata and more men when India shifted the LTTE training to Bangalore cantonment.

Pirapaharan set up his arms purchase network during the closing months of 1983. Adele Balasingham, in her The Will to Freedom, records that the Tigers used a portion of the funds MGR provided (details about MGR’s contribution will be given later) to purchase arms from abroad. “Indeed on one occasion,” she recalls, “the rooms in our house was full of AK 47s and rocket propelled grenades. Similarly, millions of rupees were stored in the wardrobe of our room.”

Uma Maheswaran was the other militant leader who decided to build up an independent arms stock. However, his weapon ship, which berthed in Chennai harbour with guns and other arms worth 40 million rupees, was confiscated by the Indian customs. All his effort to get it released failed. That incident gave the Tamil groups a clear message that India did not want them to be independent of Indian arms. But Pirapaharan managed to smuggle in arms without Delhi’s knowledge and with the cooperation of Tamil Nadu officials.

Pirapaharan’s effort to build training camps was actively promoted by Tamil Nadu politicians. He established two large training camps in Tamil Nadu by the end of 1983. The first camp was opened at Kulatur, near Mettur in Salem district and the second at Sirumalai near Dindugal in the Madurai district. Kulatur Mani, an activist of Dravida Kazhalagam helped the establishment of the first camp. He organized the procurement of food grains for the camp from the nearby villages. Nedumaran did the same for the camp at Sirumalai.

Prabhakaran with Kolathur Mani of DVK

Kulatur Mani and Nedumaran, who continue to support Pirapaharan and whom Pirapaharan holds in high esteem, have given detailed accounts of their role to journalists. Mani, now 56, son of a forest contractor, who was involved in the Veerappan controversy two years ago, told an Indian journalist, “Yes, I first ran the LTTE camp in the garden of my house in Kulatur. Then I found them a convenient location.”

Mani said he used to visit the site during construction. “On some occasions I have travelled with him,” he told an interviewer.

One of the cadres who was involved in the construction of the Kulatur camp has given an account of their endeavour to a pro-LTTE publication. He said, “I think it was in November 1983. We travelled from our Madurai safe house in a bus. We got down in a hilly forest. Our guide took us along a mud track and then along a footpath. We walked for about six-hours. Then we reached a rocky terrain. ‘This place is ideal for your training camp,’ the guide announced.”

And that rocky terrain was turned into a massive training complex, the cadre wrote. The cadres built everything from scratch. They cleared the ground. They built temporary cottages. They turned the footpath into a motorable track. Pirapaharan visited the camp very often. He planned the camp and oversaw the construction. In the evenings he trained in pistol shooting.

The Sirumalai camp and a couple of small camps near Thirparankunram and Azhagarmalai in Madurai were added later.

The premier training camp of PLOTE was in Orathanad in Tanjore district. PLOTE had another camp at Theni, a scenic site on the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border in the Madurai district. PLOTE youths marched every morning from their camp to the hill for firing practice. PLOTE was the largest group at that stage. In 1984 its camps overflowed and it hired a kalyana mandapam (Wedding Hall) at Nandanam in the heart of Madras. They did their physical exercises in the top floor of the mandapam.

TELO had its main training base in the Kolli hills in the Salem district. It had another at a village called Magaral near Kanchipuram and also at Porur near Madras.

The EPRLF’s main camp was situated near Kumbakonam in Tanjavoor district and smaller camps in Skandapuram, Tirichy and Palani.

EROS set up its cam in Meenampakkam in Chennai, Vetharanyam and Thankachchimadam in Ramanathapuram.

By end of 1984 the number of training camps in Tamil Nadu had grown to over 30.

According to Delhi sources, “A few camps were started to begin with. In their full bloom there were around 30 camps, big, small and medium. Every militant group had its own camp in Chennai and ten other districts.”

The local population was aware and, in most instances, directly helped the ‘boys,’ painyangal for them by providing their foodstuff and other needs. Most of the villagers who lived near these camps were emotionally involved in the Tamil resistance. In many places local boys wanted to join the training. All the militant groups refused to take them in. Uma Maheswaran told me there were persistent requests from local youths. “I dissuaded them by politely telling them that the victory against the Sinhalese would be meaningful and be great if we do the fighting. They were thrilled when I tell them, “Veerath thamizhalargal nangal. Thanithupp poriddevelvom meaning ‘We are Tamils with valour, we can win alone.'”

The Jail Break

The Sri Lankan army gathered bits and pieces of information about Tamil youths sneaking to Tamil Nadu for training. The Sri Lankan government was not aware of the Indian training program till November. But before that bombshell Jayewardene was shaken by the Batticaloa jail break of 23 September 1983.

Nineteen Tamil political prisoners who escaped the Welikada massacres of 25 and 27 July were transferred to Batticaloa Prison on 28 July. They were taken in an air force plane to Batticaloa Airport and in an open van to the prison situated at a place called Anaipanthy. The prison was surrounded by the lagoon.

In the Batticaloa Prison there were 22 more Tamil political prisoners mostly from the Batticaloa district, amongst them two Jaffna University lecturers, Varatharaja Perumal and Mahendrarajah. The two lecturers had been sent by the EPRLF Jaffna branch to address the Karl Marx centenary seminar organized by the EPRLF Batticaloa branch at Sathurukondan. Police swooped down and arrested the organizers and the lecturers. The arrested included Siva, Mani, Kumar, Vadivelu and Sriskandarajah, all members of the EPRLF central committee. EPRLF leader Pathmanabha was also present at the seminar. He was not arrested because the police was not aware of his presence.

At the time of the jail break there were 41 political prisoners and about 150 other prisoners incarcerated, Tamils, Muslims and Sinhalese. Some of them were hard core criminals.

Paramadeva from Batticaloa was serving a jail sentence at that time. He was one of the early convicts under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. His jail term was to end in a few months, but he joined the group that planned the jail break.

A high level police team visited the Batticaloa prison in August to record the statements about the massacre of the 19 remand persons transferred from Welikada prison. The 19 prisoners jointly decided to boycott the inquiry. The police officers called them individually and questioned them about the incidents that occurred at Welikada. Every one of them boldly told the investigators that they did not have confidence in them and refused to make any statement. The police officers were annoyed and visibly exhibited their annoyance.

Following their departure, prison officials told the Tamil political prisoners that there was a move to transfer them to a high security prison newly built in the Sinhala area.

“We felt that they are taking us back to kill us. So, we decided on the jail break,” one of those who escaped told me. He said the decision to escape was jointly taken and planning and execution was a joint effort.

N. Manikkadasan (C), the military wing leader of the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE) flanked by bodyguards during a local council election campaign in Jaffna, 29 January 1998.(EPA photo-AFP files)

Naturally, young militant leaders Douglas Devananda, Manikkathasan, Paranthan Rajan, Panagoda Maheswaran, Paramadeva and others provided leadership.

My source said that it was clearly agreed that the joint action would last till they got out. Thereafter each group should work out its own way of escape.

“Planning was carefully done,” my source said. The general plan of escape was to overpower the jailor and the seven jail guards, tie them up and plaster their mouths and escape through the main gate. Duplicates of the keys of the main gate was made using the impression they made on soap. Devananda, Manikkathasan, Maheswaran and Paranthan Rajan, all able bodied youths, were given the responsibility of overpowering the prison officials. Varathaja Perumal, who at that time did not belong to any militant group, and Alagiri of EROS were assigned the task of breaking the rear wall and making an opening to be used if they failed to open the main gate. David and Dr. Jayakularajah were given the task of plastering the mouths of the jailor and jail guards.

The time for escape was very carefully determined. The jail entrance was guarded by one jail guard. An army patrol visited the prison every 15 minutes. In between a police patrol did a round. That gave the escapees just seven minutes.

The escape was planned for the night. It has to be at a time the roads were not crowded, yet not completely deserted. The time picked for escape was 7. 25 p.m. and should be over before 7.32 p.m. – that is, the escape should be after the army patrol left and police mobile arrived.

Smuggling of weapons was left to the military men. Devananda and other EPRLF cadres worked through the EPRLF, which also made arrangements for their transport. EPRLF central committee member Gunasekaram was at the gate to receive his men. Manikkathasan, Paranthan Rajan, Vamathevan, Farook and David got their weapons from PLOTE, which also made arrangements for their transport. Panagoda Maheswaran, the Tamil Eelam Army leader, told the others that he and his two men, Kali and Subramaniam, would escape in a boat through the lagoon.

Nithiananthan, his wife Nirmala, Fr. Sinnarasa, Rev. Jayathilakarajah, Dr. Jayakularajah and Fr. Singarayar were LTTE sympathizers. Fr. Singarayar told the others that he was not prepared to escape. His age and health would not permit him to. Besides, he took a high moral stand. Escaping would amount to admitting guilt, he argued. Nithiyananthan told the others he and his wife would look after themselves.

Kovai Mahesan was sick and Dr. V. A. Tharmalingam was too old to escape. Besides, they were not arrested like the others under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. They were arrested under Emergency Regulations and would be released any time. They decided to stay back. Fr. Singarayar, Kovai Mahesan and Dr. Tharmalingham were freed in early November 1983.

The arms the prisoners were able to smuggle in were few, so they cut old slippers in the shape of pistols to scare prison officials and other prisoners. Panagoda Maheswaran undertook that endeavour.

“We prayed and waited for the appointed minute. An hour before the designated minute Fr. Singarayar met the others and blessed them and wished success,” my source said.

Around 7 p.m. jail guard Anthonipillai took tea for the political prisoners. He was jovial after his usual evening drink. He was humming an old film song.

“Eppidi Irukkiriyal Thambikal? (How are you all, younger brothers?)” he greeted them.

Paranthan Rajan caught and tied him up. David plastered his mouth. Panagoda Maheswaran, a well built, handsome six-footer, overpowered the jailor and the others the other jail guards. The prisoners made a beeline to the gate and escaped.

Varatharajah Perumal and Alagiri, who were breaking the rear wall, suddenly felt an unusual silence had descended. They ran to the front gate to see what was going on. It was open. They ran out and went round the prison. They saw the boat carrying Maheswaran and his associates. They shouted. The boat returned and picked them up.

Vamathevan, Thanthai Chelva’s former driver, for whose arrest police had offered an award of Rs. 100,000, was assigned the task of breaking into the section in which Nirmala was kept. He forgot about Nirmala in the rush.

The EPRLF and PLOTE men were transported to a forest footpath. They walked together some distance and parted ways, each group walking to the designated point in the coast from where they picked by separate boats and were taken to Tamil Nadu.

The LTTE group – Nithiananthan, Fr. Sinnarasa, Jeyakularajah and Jayathilakarajah – ran behind the prison. Parmatheva also joined them. They crossed to Manthivu, about 600 meters away, in a boat. They heard shots fired in their direction. It was dark and they moved faster to Muthalikuda. Then they hijacked a tractor and drove to Thirukovil. There they stayed in a hideout until they went by boat to Tamil Nadu.

Panagoda had other plans. He wanted to stay in Batticaloa. He wanted to carry on the struggle and do something stunning. He went into hiding in Batticaloa though the region was not familiar to him. He was born and educated in Jaffna and went to England for higher studies. He did something stunning within a few months. He robbed a bank in Kattankudi of gold, jewellery and cash worth Rs. 35 million, the biggest bank robbery till then. More on that incident later.

The escape, which David has called “a thrilling episode in the history of the Tamils,” shocked the fellow prisoners more than anyone else. They found Tamil political prisoners running out and the heavy iron gates ajar. They also ran out.

When a mobile police unit arrived as scheduled at 7.32 p.m. they found the prison virtually empty. The police and the army launched a massive manhunt, an intense land, sea and air search. Police rounded up some of the prisoners, mostly Sinhala prisoners, who were stranded in the town unable to make a getaway.

Next: Chapter 13. The Love Story

To be posted August 27