by Sachi Sri Kantha, April 1, 2013

MGR biographies in English An evaluation

As of now, the completed six parts in this series amounts to over 18,000 words. It is my view that MGR’s pre-hero phase during the first 30 years of his life has not been covered in such detail, for lack of attention and want of materials by his biographers. I acknowledge the help of my friends and fans (N. Ramarathnam, A. Vijayaraghavan, A.M. Pandian, S. Sivakumaran and Yoshitaka Terada) who had gifted me complimentary copies of books and reprints of articles on Tamil movies and music which cover the pre-1950 period. Their kindness as well as my assembled collections over decades had helped and stimulated me in scribing this MGR story.

Initially, I planned to stop this series after five parts. But encouragement via emails received from few lifted my spirit to continue this series. Next month, I’ll reach 60, and I have been an avid fan of MGR for 50 years since I watched one of his Thai (mother)-movies Thai Sollai Thattathe (Don’t Reject Mother’s Words) in 1962 at the now demolished Plaza theatre in Colombo. In the second half of 1960s, when I was a student at the Colombo Hindu College, Ratmalana, I vividly remember participating in the cinema-politics discussion about Tamil Nadu daily with one of my classmates of Indian Chettiar origin. His name is Veerappan. Our dimunitive for him was ‘Veera’. His father’s name is Sivalingam Chettiar. From 1964 to 1968, we used to have debates on what MGR or Annadurai did was correct or not in between class hours. He was a pro-Congress (leader Kamraj) supporter. In between class hours, we used to duel verbally on the DMK-Congress conflicts in Tamil Nadu. One thing which I liked in my interactions with Veera was that he was privy to informal (or ‘off the record’ in journalism parlance) ‘Chettiar network news’, and he would routinely deliver us many Tamil Nadu stories which we hardly received from daily newspapers or radio or even in books.

Why do I reminisce about Veera here? I remember him mentioning that his father was also involved in financing or producing a Tamil movie (with actress Padmini as one of the lead players) and something drastic happened, and lost all the capital. Then, some of his relatives or friends lent him little money for passage to Ceylon, to establish himself in a new field of business. That’s how, his family landed in Colombo. His father became a successful businessman in 1950s, and by late 1960s he returned to Tamil Nadu with his family. As MGR had mentioned the role of Nagarattar or Chettiar (mercantile bankers) community as the patron of dramas in his autobiography (part 4), we also note from the reminiscences of Ellis Dungan (presented below), that they were also the life-line and patrons for the budding Tamil movie industry in 1930s.

Though there have been numerous short adulatory biographies of MGR in Tamil (about which M.S.S. Pandian had critically commented in his book – see below), I’m of the opinion that his story deserves a good treatment in English. In this respect, he has been poorly served. I wanted to rectify this lacuna and continue this remembrance series. Previously, I have written short commentaries and review of books about MGR in English and six are accessible in the internet.

(1) Role models for heroism among Tamils

(2) MGR: The Man from Maruthur & Malainadu

(3) MGR, the man and the myth (K. Mohandas) – book review.

(4) On Milton Friedman, MGR and Annaism (2006)

(5) The ‘Birth-soil bond’ of MGR; an 89th birth anniversary note (2006)

(6) Kannadasan’s minor book(let) on MGR: Random notes (2011)

I assembled this list to claim my authority as the writer of these items. In the internet platform, in a number of MGR fans’ websites and blogs, I notice with a tinge of sadness that my name had been clipped off in re-posting the originals. This type of vandalism and plagiarism deserves criticism and it is my wish that the culture of requesting prior permission from the authors for posting deserves recognition. I was also amused that my item titled ‘On Milton Friedman, MGR & Annaism’, had been cited in a Wikipedia entry on Socialismo (in Spanish), as reference 37, devoid of author’s name, though the original version as it appeared in the sangam site carried the contributor’s name!

MGR biographies in English

To my knowledge, there have appeared four MGR biographies in English. These are,

Attar Chand: M.G. Ramachandran –My Blood Brother (1988)

K. Mohandas: MGR: The Man and the Myth (1992)

M.S.S. Pandian: The Image Trap – M G Ramachandran in Film and Politics (1992)

Roopa Swaminathan: M G Ramachandran – Jewel of the Masses (2002)

The Hindu daily published a brief three paragraph review for Attar Chand’s biography. It was as follows:

“This is the story of a charismatic leader who ruled the hearts of millions of men, women and children of Tamil Nadu who felt orphaned when he died in December 1987. The filmstar-turned politician, MGR, guided the destiny of the State for almost a decade when he implemented a number of anti-poverty programmes, particularly to benefit the weaker sections, women and children.

In this biography, the author has brought out vividly not only MGR’s journey from rags to riches but also his achievements as the unquestioned leader of the AIADMK party and Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. The book ends with the widow of MGR, Janaki Ramachandran’s induction as Chief Minister who, however, stayed in office hardly for a month.

For his work, Attar Chand has made liberal use of the material published in different newspapers. While one cannot belittle the performance of the AIADMK Government, not everybody will agree with some of the observations of the author, especially with regard to success in eradicating corruption and reaching outstanding levels in the industrial and economic fronts.”

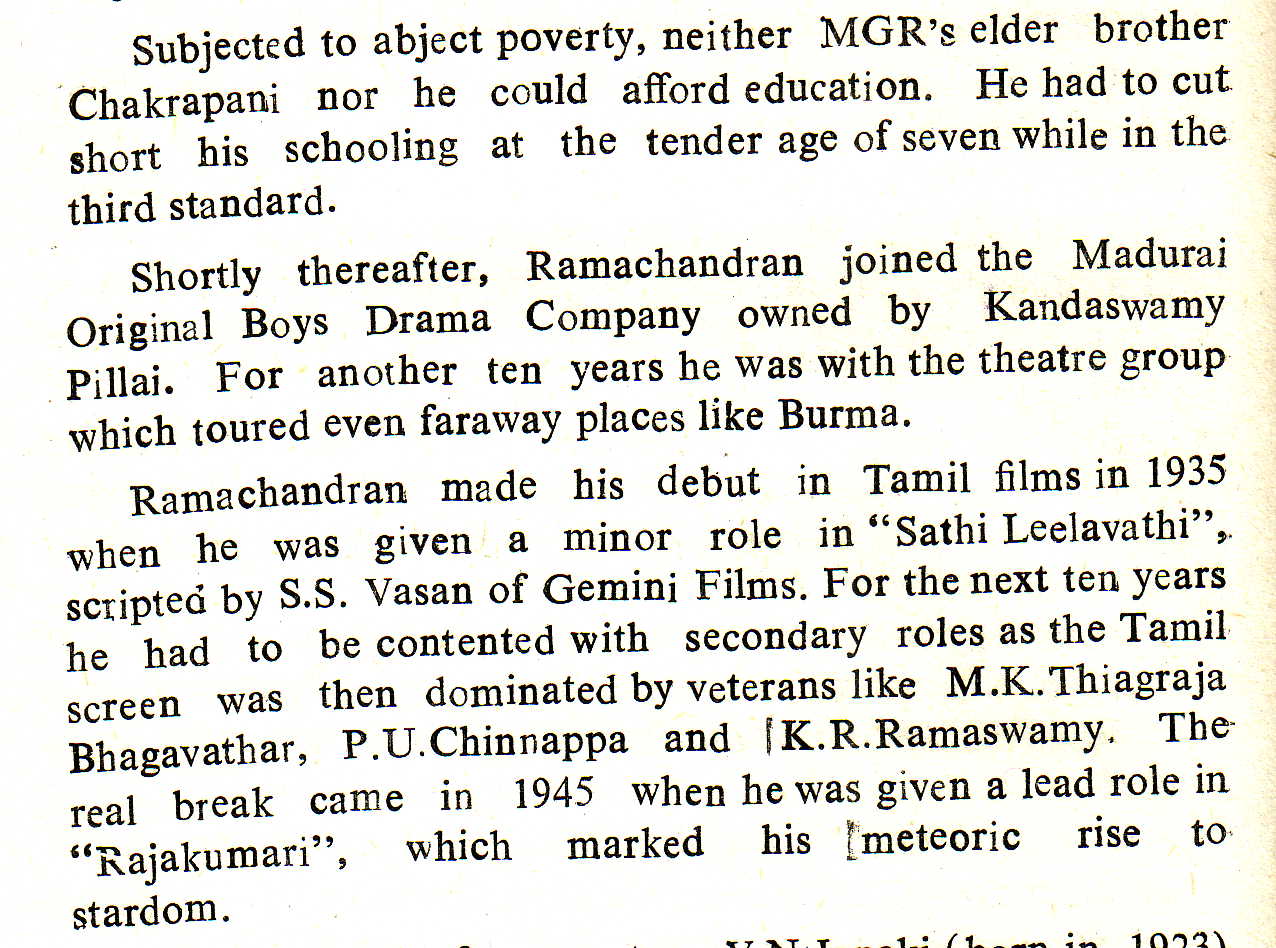

The reference to AIADMK in the review relates to All India Anna DMK, the party founded by MGR in 1972, after he was evicted from the DMK party, which he joined in 1953. To reinforce my point presented in the first paragraph, I provide a scan of material from Attar Chand’s book. MGR’s first 30 years were covered in only three paragraphs! The same was true in Pandian’s book as well. Mohandas hardly touched this period. I provide my comparison on the little merits and big demerits of these biographies, and their effect on my long term interest in preparing an authentic work on MGR. A PDF table with 17 comparative criteria which I prepared is offered nearby. As I provide my grade for each of these four biographies, Attar Chand’s biography of 1988, was a ‘quickie’, assembled immediately after MGR’s death. 1992 saw two more biographies. While, Mohandas’s work was a ‘friendly’ one, Pandian’s essay was sloppy. Ten years later, Roopa Swaminathan brought forth a skinny book for younger readers, with most of the material borrowed from Pandian’s book.

Another book which is of interest was by Tamil movie chronicler Randor Guy (pen name) with the title, Starlight, Starbright – The Early Tamil Cinema (1997), which carries chapters on the production background MGR’s first movie Sathi Leelavathi (1936) and its associated artistes Ellis R. Dungan (the director) and movie mogul S.S. Vasan (the script writer). Randor Guy also contributed a short chapter on MGR in this book.

Impressions of Ellis Dungan

I provide below excerpts of Ellis Dungan (1909-2001), a Barton, Ohio-born American who landed in Madras in 1935, after studying cinematography at the University of Southern California, through the courtesy of his Indian pal Manik (Munnay) Lal Tandon. It was through Tandon’s introduction, Dungan came to direct the Sathi Leelavathi movie.

“Our first impression of Madras was the friendliness of its people. We were simply overwhelmed with their kindness and hospitality and were besieged by local film journalists and news-hounds for interviews. It appeared that we were the first Americans with any Hollywood know-how and experience to touch down there. ..In 1935 when we first arrived there, Madras had a population of 750,000; it probably now has around 5 million residents.

Following the ‘blockbuster’ release of Nandanar, Tandon had an offer to direct a Tamil film titled Sathi Leelavathi (Sathi meaning self-immolation by Indian widows, and Leelavathi being the name of the leading female character in the movie). Tandon asked if I would like to direct the film as he had a previous offer to direct Shame of the Nation in the Hindi language (his native language) at a Calcutta studio. I said to him, ‘Sure, I would like to get my feet wet and go where the action is.’ Tandon replied, ‘I’ll be with you whenever I can.’

The Madras producers knew Tandon well, and he had a good reputation in Madras. But I was new and the producers were a little afraid of an unknown American coming over to direct Tamil films. However, they finally agreed and said, ‘Okay, if Tandon is with you, we will sign the contract.’ So were were off and running, but Tandon could not stay long in Madras…”

Dungan’s ethnological experience with caste-bound Tamil society in 1935 is worth repetition for its relevance. This also offers a tangential glimpse on how the social-liberation role played by E.V. Ramasamy Naicker and his lieutenant C.N. Annadurai (Anna) in 1930s worked in attracting the majority Tamils to their cause and how Anna became an influential script writer in late 1940s. Dungan had written,

“As an American, I was considered to be of the lowest caste, that is, a pariah or an outcast. Being considered an ‘untouchable’, I was unable to enter their temples to direct my pictures. (The Constitution of India has now legally abolished untouchability). When filming a temple scene, I would have to stand outside on top of a wall and shout directions to my English-speaking Indian assistants inside. My assistants would then relay my directions to the actors. However, that never worked out very well. One day while directing a scene for my first film, I dressed as a North Indian Brahmin from Kashmir. They are fairer-skinned, so by putting on an Indian dhoti and upper garment and smearing my face with dark Egyptian makeup, I was able to enter the inner sanctum to direct the scene. The following day the temple priest learned that I had been in the temple and ordered the floors and walls to be scrubbed down. Then another time an Indian Brahmin friend, a journalist, was forced to pay fifty dollars to have a temple cleansed because I sat on the floor of the temple to witness his daughter’s wedding (at his invitation).”

I provide four paragraphs from Dungan’s experience with Sathi Leelavathi production and its after-effect.

“With Sathi Leelavathi, my first film in India, I had much to learn. Some of the cameo incidents during its production left a lasting impression on me, such as when the Vel Pictures studio manager, Mr. Ramamurthi, used to clean all the exposed negatives by hand – inch by inch, frame by frame. It was unbelievable that he would go through fourteen or fifteen thousand feet of film in this manner. It seemingly took days to clean the exposed negative of a complete motion picture film. (Ramamurthi later became assistant manager at the Kodak film distribution offices in Madras.)

Late one night, Sircar, my film editor, and I were cutting the final version of Sathi Leelavathi. Our producer, A.N.M. Chellam Chettiar, was lying nearby on the editing room floor, sleeping and snoring loudly. It disturbed us so much that we playfully decided to cut off his big mustache while he slept. But at the last minute I got a little funky and said no; ‘This may be my first, and last, picture in India if I cut off his mustache.’ So we let him snore away….

The story of Sathi Leelavathi was based on a novel turned stage play, and the actors were actually a stage troupe. Later I jokingly told friends that when a stage troupe came to the cinema, they brought the ‘stage’ with them, and as a result, in the early days of filmmaking in India, the acting had a tendency to be very ‘stagey’. As we know, the camera enlarges facial expressions and body features, and a film actor or actress has to tone them down a little and not exaggerate expressions as is done on the stage. Also some of the actors had never appeared in front of a motion picture camera before and it frightened them, whereupon they would often ‘freeze’ and couldn’t speak.

In spite of its all, Sathi Leelavathi proved to be quite a success at the box office. As a result, I was offered other pictures to direct. With this, my first film in India, I broke into the film business ‘at the top’, when most directors had to start at the bottom and work up…”

The cast and plot for Sathi Leelavathi movie

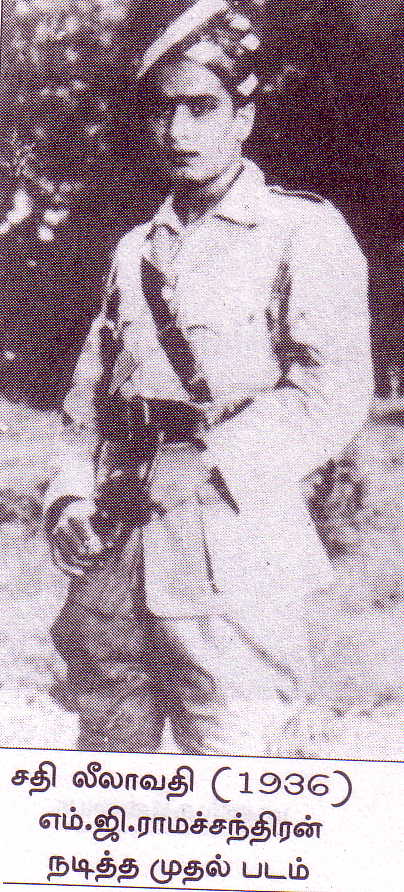

MGR appeared in his debut role as a sub inspector of police. When Sathi Leelavathi movie was released on March 28, 1936, he was barely 19 years and 2 months old. Apart from MGR, it was also a debut movie for other actors who made a deep impact in Tamil movies for decades. The hero of the movie was Madras Kandasamy Mudaliar Radha (no relation to actor M.R. Radha, who had a tiff with MGR in 1967 and shot him), whose father Kandasamy Mudaliar was the chief sponsor of the movie. The villain role was played by Tirunelvely S. Baliah (renowned multi-talented character actor). Comedian Nagarkoil Sudalaimuthu Krishnan also debuted in this movie. Another debutant was Subramaniam Srinivasan aka S.S.Vasan as a story-originator, later to gain status as a movie mogul.

According to Randor Guy, the movie plot was lifted and adopted to Tamil Nadu background from Danesbury House (1860), the first novel by an invalid British women author Mrs. Henry Wood aka Ellen Price (1820-1887), who suffered from scoliosis. As it was a temperance story, it fitted well with the anti-alcohol campaign by Indian freedom fighters. The plot in brief, as provided by Randor Guy: the hero (M.K. Radha) ill-treats his wife (Gnanambal, Radha’s real life wife), after being influenced by alcohol and induced by villain (Baliah). On one occasion, he also fires a pistol at his friend and thinking that he had committed a murder escapes. Then, to evade from police hero flees to Ceylon to work in a tea estate and strike it rich after discovering hidden treasure. Hero then returns to India and live under a disguise to escape from police. Subsequently, he was caught, tried for murder and sentenced to death. At the appropriate climax, the police inspector (MGR) turns up with evidence that relieves the hero from murder charges and the villain being nailed. The hero re-united with his wife. Randor Guy informs that though Sati Leelavathi earned its place in the history of Tamil cinema, “no print of this film is known to exist today.”

Sathi Leelavathi’s standing in comparison to other Tamil movies of 1936

The first Tamil movie (talkie) was released in 1931. In the succeeding years, the number of Tamil movies released increased as follows: 1932 – 4 movies, 1933 – 8 movies, 1934 – 14 movies, 1935 – 32 movies, and 1936 – 38 movies; MGR starred in bit-parts in two, of which Sathi Leelavathi was the first. For record, a total number of 217 movies were released in India in all languages (Hindi 134, Tamil 38, Bengali 19, Telugu 12, Marathi 6, Gujarathi 4, Kannada 1 and the rest in other languages) for the year 1936. For reference, I provide the names of 38 Tamil movies released in 1936 and the name of lead actor within parenthesis below. Onomastics of the movie titles reveal that majority were based on Hindu religious, epic and mythological names (such as Indra, Krishna, Arjuna, Kusela, Chandra, Nalayini, Parvathi, Bhisma, Rukmini, Viswamithra, Abimanyu) and historical Hindu saints (Pattinattar, Meera, Kabir). Only a few like Iru Sahothararkal (Two Brothers), which was MGR’s second movie for the year, was based on social theme.

Ali Padhusha (C.S.Selvaratnam)

Bhama Parinayam (Serukalatoor Saama)

Bhishmar (M.S.Thamothara Rao)

Chandrahasan (V.N.Sundaram)

Chandrakantha (Kali N. Ratnam)

Chandramohana (M.K. Radha)

Dharmapathini (V.A.Sellappah)

Indra Sabha (T.K.Suntharappa)

Iru Sahothararkal (K.P. Kesavan)

Karuda Karvabangam (M.D. Parthasarathi)

Krishnanarathi (K.V. Vaithianatha Aiyar)

Krishna Arjuna (K.V. Seenivasa Bhagavathar)

Kuesela (Papanasam Sivan)

Madras Mail (Battling Mani)

Maha Bharatham [Srimath] (Annaji Rao)

Mahatma Kabirdas (P.D.V. Krishnan)

Manohara (P.G.Venkatesan)

Meerabhai (C.V.V. Panthulu)

Miss Kamala (C.M. Durai)

Naveena sarangadhara (M.K. Thiyagaraja Bhagavathar)

Nalayini (C.S. Selvaratnam)

Nalayini (K.V. Vaithianatha Aiyar)

Paduka Pattabhishekam (M.R. Krishnamoorthy)

Parvathi Kalyanam (P.S. Seenivasa Rao)

Pattinattar (M.M. Thandapani Desigar)

Pathi Bakthi (K.P. Kesavan)

Ratnavali (M.R. Krishnamoorthy)

Raja Desingu (T.K. Suntharappa)

Rukmani Kalyanam (Nadesa Aiyar)

Sathi Leelavathi (M.K. Radha)

Sathyaseelan (M.K. Thiyagaraja Bhagavathar)

Seemanthini (M.R. Krishnamoorthy)

Srimathi Parinayam (?? not indicated)

Tharasa saangam (G.S. Vijaya Rao)

Usha Kalyanam (C.V.V. Panthulu)

Vasanthasena (V.A. Sellappah)

Veera Abimanyu (M.R. Krishnamoorthy)

Viswamithra (M.K. Gopala Aiyangar)

Among the lead actors, only M.K. Thiyagaraja Bhagavathar and M.K. Radha were able to climb to the superstar grade in 1940s. Among the rest, (1) some attained fame as musicians (M.D. Parthasarathi, MM. Thandapani Desigar), (2) one attained fame as a Tamil composer-lyricist (Papanasam Sivan), (3) one became a playback singer (V.N. Sundaram), and (4) few stood out later as actors in supportive roles (P.G.Venkatesan, Serukallatur Shaama and Kali N. Ratnam). But, majority faded out within a few years.

As Barnow and Krishnaswamy had observed in their pioneering work Indian Film (1963), in 1930s, “Although some performers were ‘stars’ in that they were widely known and featured in publicity, no real star system had as yet developed. The star was an employee; he or she was not the pivot of planning and was not in control. Producer and director were the dominant figures. Throughout the 1930s the difference between the salaries of top actors and other actors remained small by the standards of later years. Throughout this period Rs. 3,000 per month remained the ceiling for star salaries at several of the larger companies. An established lesser actor might get Rs. 600; a beginner, Rs.60.” Thus it could be assumed that MGR’s salary for his early movies were 60 rupees per week. Author Krishnaswamy’s father K. Subramaniam (1904-1971) was a Tamil movie pioneer involved in production and direction; as such the salaries paid for actors during 1930s can be relied with full confidence.

When checking these early Tamil movies, one finds that it was not unusual to have the same names for movies, to appear in one year, produced by two different companies. For example, 1933 had two ‘Prahalatha’ movies produced by New Theaters and East India Film Company. 1934 had two ‘Draupadi Vasthrapakaranam’ movies produced by Angel Films and Seenivas Cinetone. 1935 had two ‘Nalla Thangal’ movies produced by Angel Films and Pioneer Films. So, there were two ‘Nalayini’ movies produced by Oriental Sound Pictures and Sundaram Talkies in 1936. As the plots of all these movies were based on Hindu religious themes (alternately called, puranic), no problems existed with copyright issues. Producers (mostly businessman – Chettiars) treated movies as another commodity, akin to food, condiments and clothes, to sell to the public. Majority hardly cared for artistic or esthetic merit in movie making for the illiterate audience. As, such an audience had learned the basics of religious and epic stories via the prevalent traditional story telling art forms, the polish and ‘hook’ was not in the movie titles, but focused in the faces and voices of heroes and starlets as well as the humor component linked to the main plot. 1936 also saw the same plot based on a social theme, produced by two different companies, under different names. Sathi Leelavathi and Pathibakthi belonged to this category.

Pathibakthi movie, based on plot scripted by noted playwright T.P.Krishnasamy Pavalar, and produced by Madurai Original Boys Company (to which MGR belonged) had MGR’s mentors of stage, K.P. Kesavan, Kali N. Ratnam and K.K.Perumal starring in it. MGR featured in a small role in the Sathi Leelavathi movie, along with M.K. Radha, whose father was the sponsor for this movie. According to Randor Guy, when it came to copyrights issue, the story-originator S.S.Vasan for Sathi Leelavathi movie proved in courts that both, he and the rival playwright T.P. Krishnasamy Pavalar had plagiarized the same plot of Mrs. Henry Wood’s Danesbury House novel. As such, copyright infringement clime was invalid. According to Tamil film historian Aranthai Narayanan, Sathi Leelavathi turned out better than Pathi Bakthi in revenue. This was attributed to solid performances by M.K. Radha (hero), T.S.Baliah (villain) and N.S.Krishnan (comedian), as well as publicity adapted by S.S.Vasan and the support of Independence-era politicians for anti-alcohol movement.

Ellis Dungan had remembered MGR (after his death) as follows in autobiography: “He started his career as a film actor in my first film, Sathi Leelavathi as a raw recruit in the minor role of a police inspector and also acted in Meera and Manthiri Kumari. I could see the improvement in his acting from picture to picture. MGR was a tall, handsome, and athletic-type man, admired by all, and became extremely popular with the movie goers. I am proud to say that I played a role in helping his career along. He was a talented and versatile performer and, I understand, a beloved and popular chief minister.”

Between 1936 and 1950, Dungan directed 12 full length Tamil movies and MGR starred in five of them, which included Meera (1945; Carnatic diva M.S. Subbulakshmi’s incomparable hit movie) and Manthri Kumari (1950, one of his early hero-role movies, scripted by M. Karunanidhi). One of the humorous debating topics during our school days was, whether MGR was literate in English. Many of my colleagues used to ridicule that compared to Sivaji Ganesan’s polished English, MGR’s English was of poor quality. Though he had regular schooling only upto 3rd grade, now we can be certain that if MGR’s English skills were pitiable, he couldn’t have benefitted and elevated himself from a bit-player to hero under Dungan’s direction in 15 years.

Cited Sources

‘Film News’ Anandan: Sadhanaigal padaitha Thamizthiraipada Varalaru (Tamil Film History and its Achievements), Sivagami Publications, Chennai, 2004.

Eric Barnow and S.Krishnaswamy: Indian Film, Columbia University Press, New York, 1963.

Ellis Dungan with Barbara Smik: A Guide to Adventure – an autobiography, Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, 2001.

Randor Guy: Starlight, Starbright – The Early Tamil Cinema, Amra Publishers, Chennai, 1997.

Aranthai Narayanan: Thamizh Cinemavin Kathai (The story of Tamil Cinema), New Century Book House, Chennai, 3rd edition, 2008.

C.R.: Leader of the masses. Book review of M.G.Ramachandran by Attar Chand. The Hindu (International weekly), Dec.24, 1988.

Patrick Robertson: Guinness Movie Facts & Feats, 4th edition, Guinness Publishing Ltd, Enfield, Middlesex, 1991.

I make a correction. MGR’s salary for his 1936 movies could been 60 rupees per month, and not 60 rupees per week as inadvertently indicated in the text.