by Sachi Sri Kantha, February 1, 2015

Millions of Laxman fans were saddened to hear the news that the ace cartoonist R.K. Laxman (1921-2015) had died on January 26, at the age of 93. As a tribute to his career, I present (1) four of his biting cartoons on the Sri Lankan scene, and (2) excerpts from his autobiographical reminiscences about how he created his alter ego ‘Common Man’, and one humorous episode of how Indian bureaucracy dealt with a copy of Playboy magazine, some decades ago.

Cartoons on the Sri Lankan Scene

Cartoons on the Sri Lankan Scene

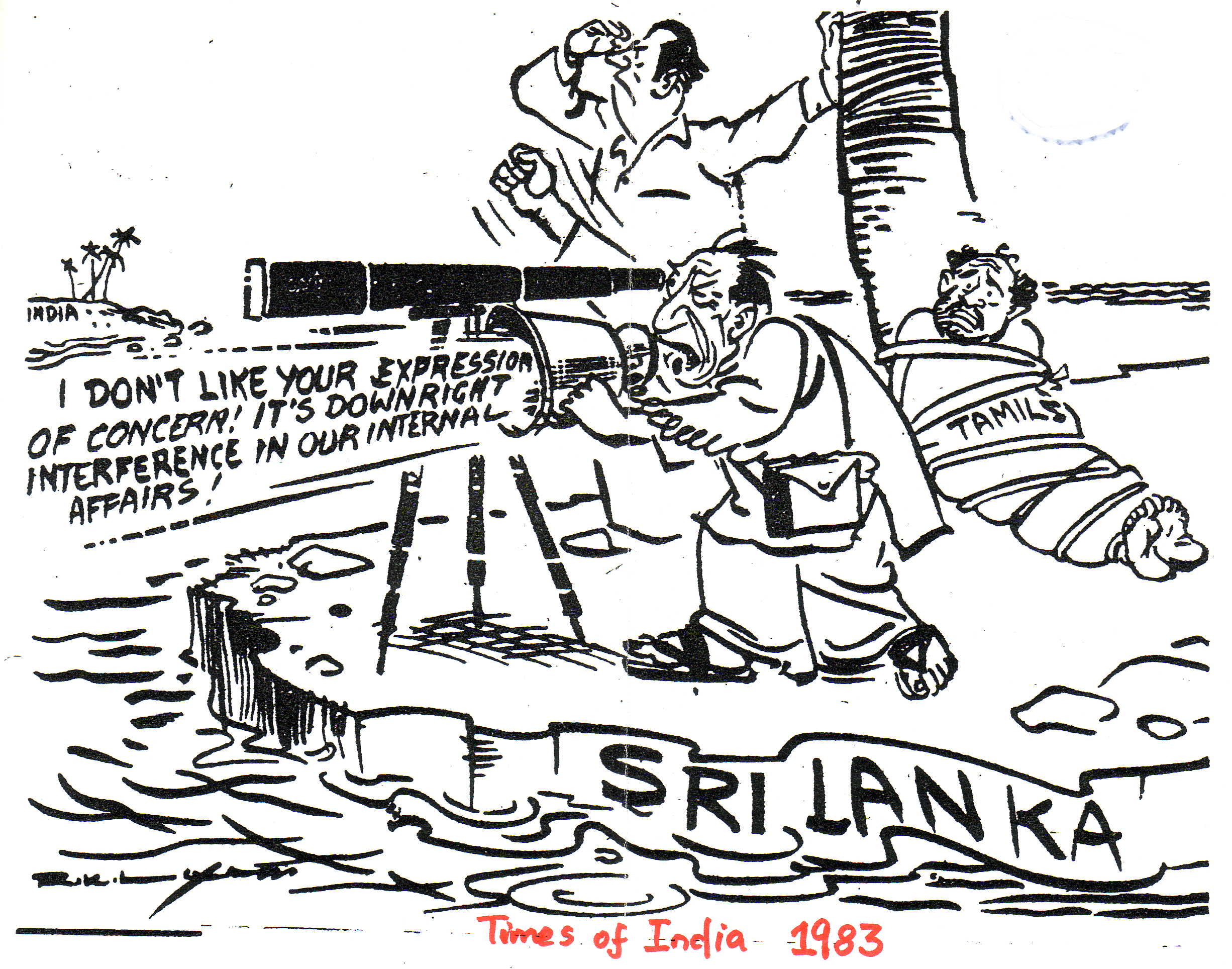

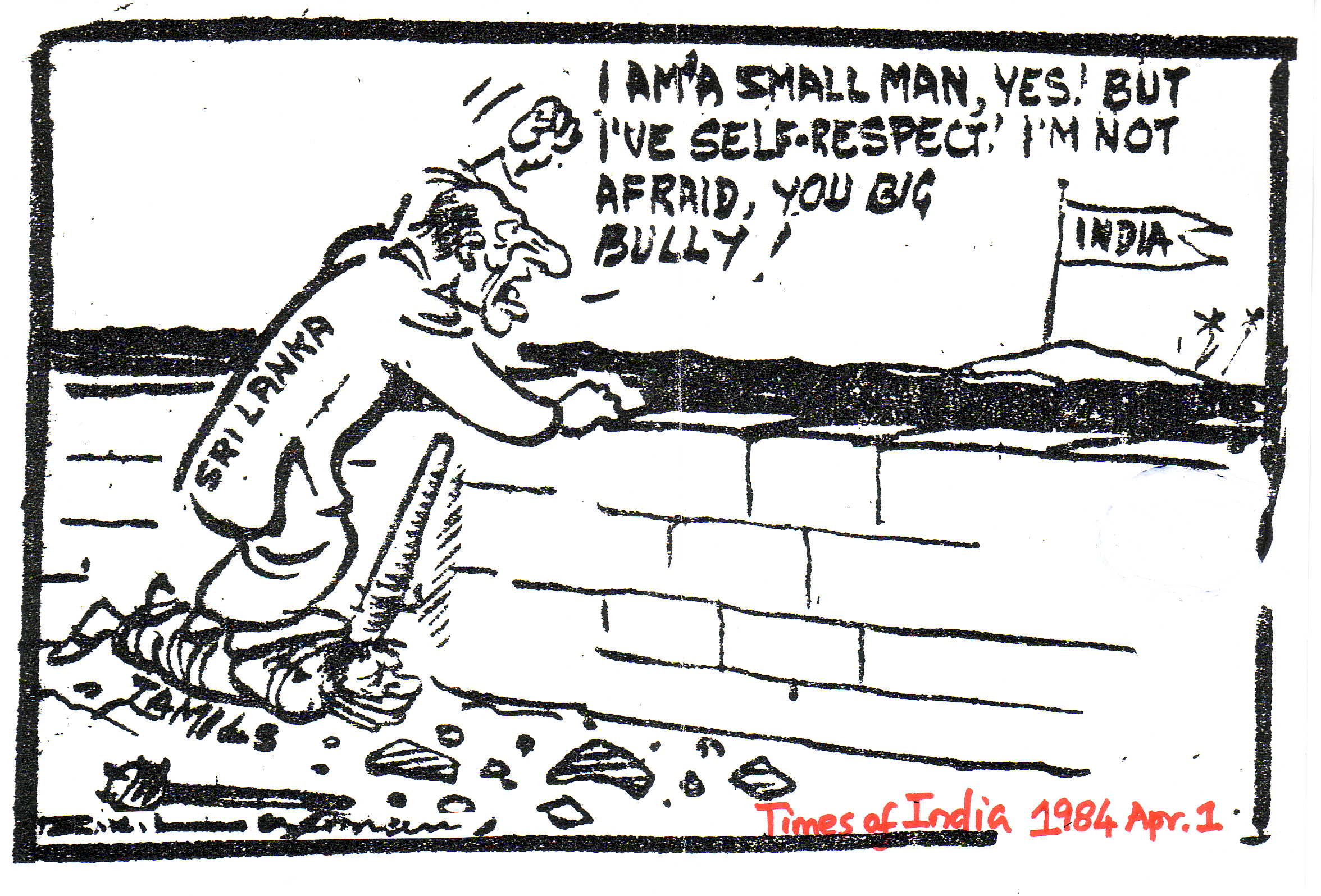

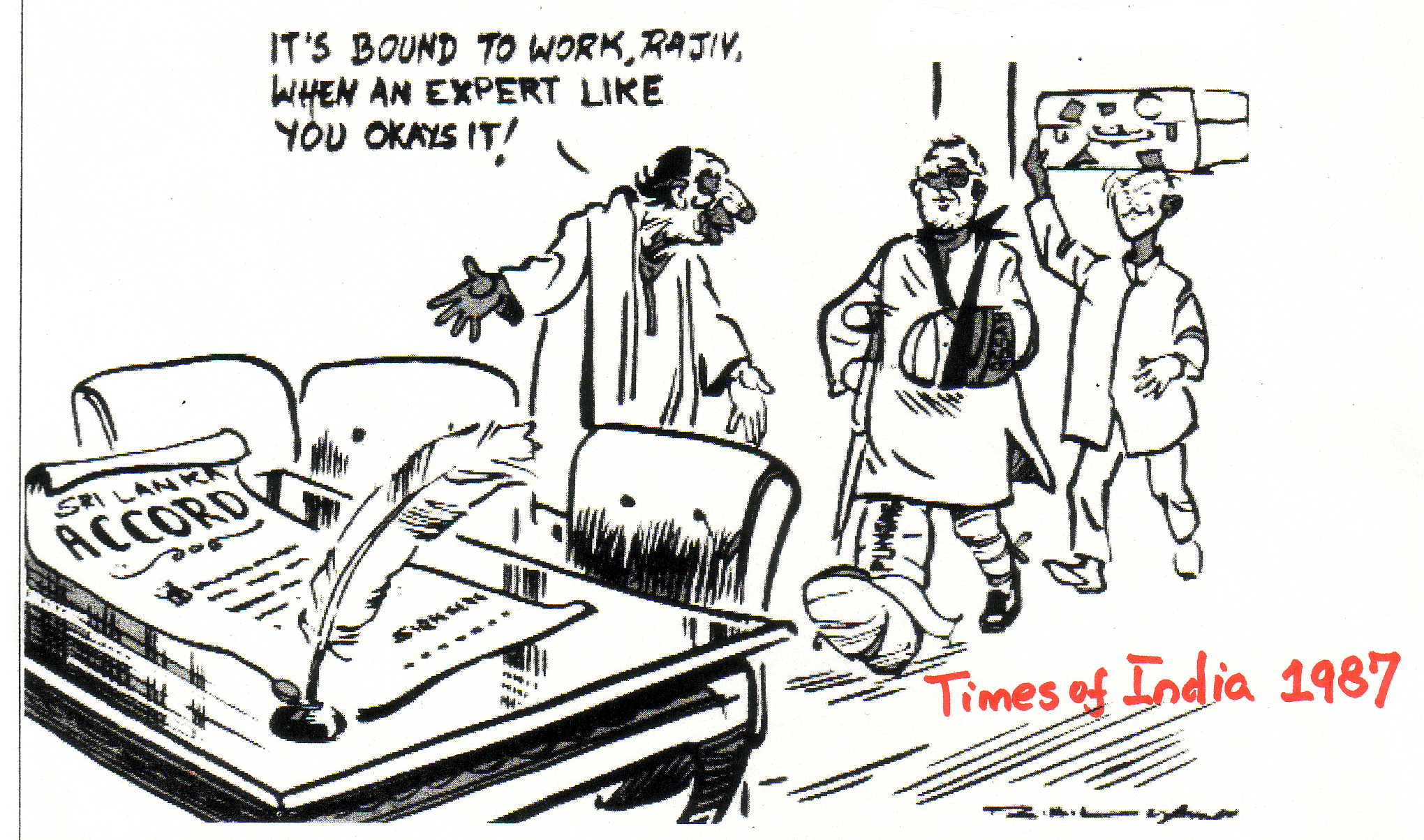

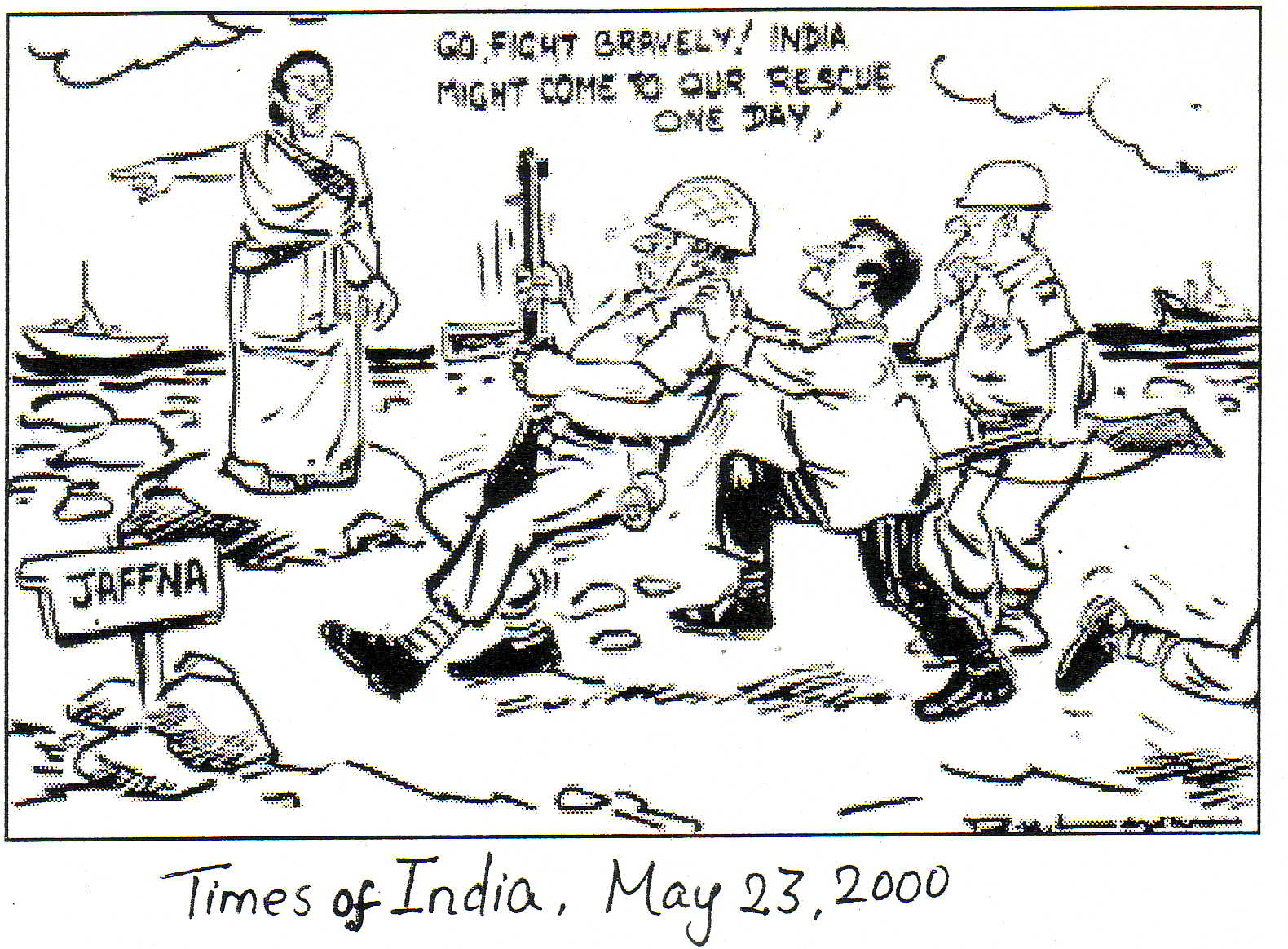

Of the four presented, three depict President J.R. Jayewardene’s deeds. Cartoons 1 and 2 were drawn, when Indira Gandhi was Indian prime minister. In cartoon 3, drawn in 1987, Indira’s son Rajiv Gandhi had been elected to the prime minister rank. Fourth one relates to the events of 2000, when LTTE tackled the Sri Lankan army stationed in Jaffna peninsula, and Chandrika Kumaratunga was the President and Minister of Defense, and her uncle Anuruddha Ratwatte was the deputy Defense Minister.

Cartoon 1: During the anti-Tamil riots of July 1983, Laxman drew Tamils plight as one who had been tied to a coconut tree, with Jayewardene shouting in a loudspeaker towards India, “I don’t like your expression of concern! It’s downright interference in our internal affairs.”

Cartoon 2: When the Sinhala-Tamil conflict escalated in 1984, Laxman focused on President Jayewardene again. He was standing on the back of hand-tied, mouth-tied Tamils, and shouting towards India, “I’m a small man, yes! But I’ve self-respect! I’m not afraid, you big bully!”

Cartoon 2: When the Sinhala-Tamil conflict escalated in 1984, Laxman focused on President Jayewardene again. He was standing on the back of hand-tied, mouth-tied Tamils, and shouting towards India, “I’m a small man, yes! But I’ve self-respect! I’m not afraid, you big bully!”

Cartoon 3: Rajiv Gandhi in hand and leg bandages, is being invited by President Jayewardene to sign the ‘Rajiv – Jayewardene Accord of 1987’. Laxman drew Rajiv as a wounded figure, wearing an eye-patch with hand bandage labelled Assam, and the leg bandage scribbled Punjab. Jayewardene’s inviting comments were, “It’s bound to work, Rajiv, when an expert like you okays it!”

Cartoon 4: This is one of my favorite Laxman cartoons. President Chandrika, standing like a Statue of Liberty, pointing to Jaffna, cheering the two Sri Lankan army guys, with her uncle Col. Anuruddha Ratwatte pushing one reluctant soldier. Chandrika’s words stated were, ‘Go, fight bravely! India might come to our rescue one day!” The beauty in this cartoon, is the one leg of another soldier who was running away from the sign board showing direction to Jaffna.

Excerpts from Laxman’s autobiography ‘The Tunnel of Time’ (1998)

Excerpts from Laxman’s autobiography ‘The Tunnel of Time’ (1998)

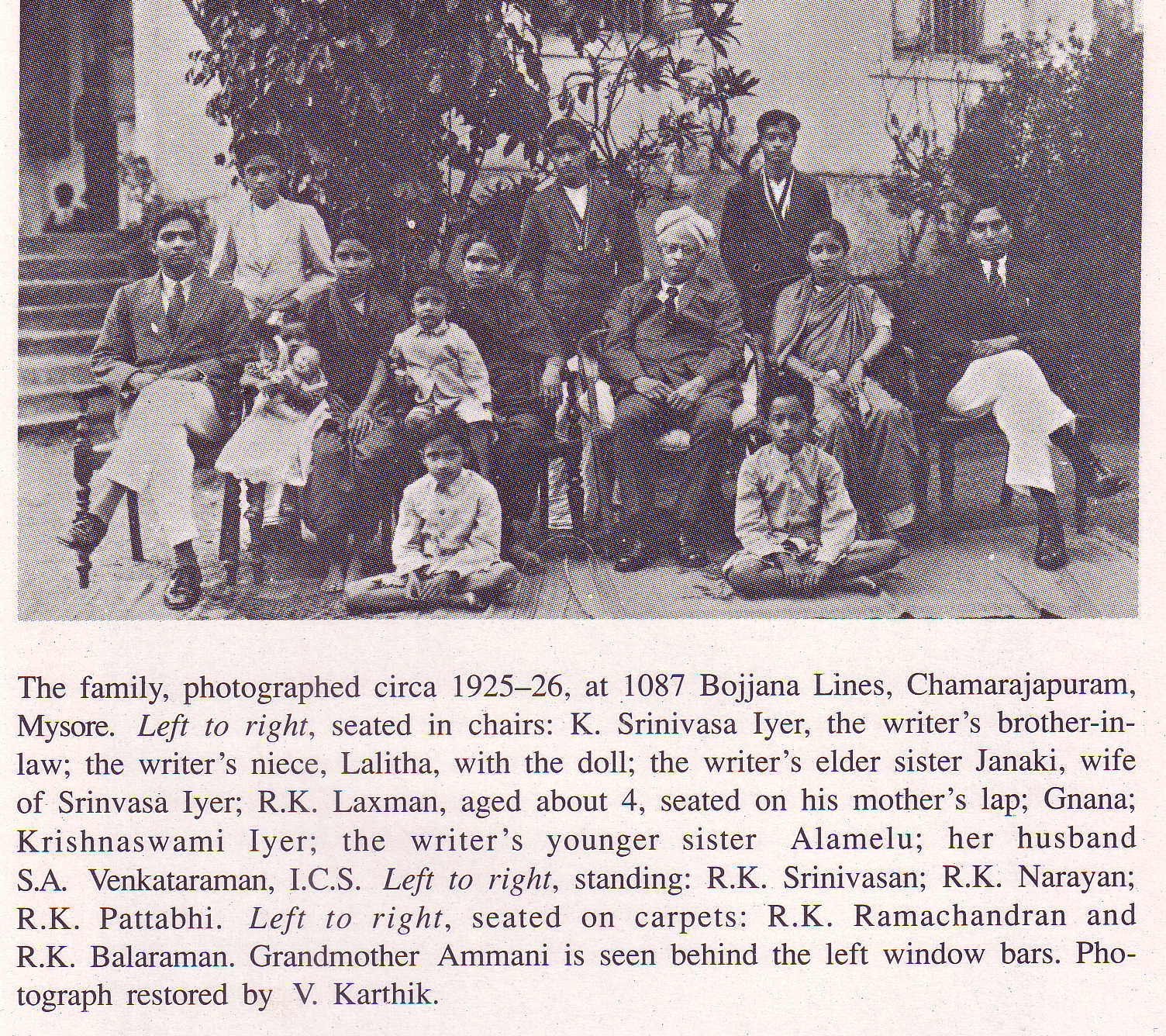

Laxman was the youngest sibling of 8 children born to R.V. Krishnaswami Iyer and Gnanambal. His eldest siblings were Janaki, R.K. Narayan, Alamelu, R.K. Srinivasan, R.K. Pattabhi, R.K. Ramachandran and R.K. Balaraman. Among these, R.K. Narayan (1906-2001) established himself as one of the foremost English writers in India.

Laxman’s 237 page autobiography was published in 1998. One demerit in this short autobiography was that, it doesn’t contain even a single photo!. Maybe, it was Laxman’s choice to hide some of his past relationships, especially his failed first marriage to dancer and actress Kamala. I have scanned and present nearby a family photo (circa 1925-26) of Krishnaswamy Iyer clan, in which Laxman is seated in the lap of his mother. This photo appears in the vol.1 of the biography of writer R.K. Narayan, authored by Susan Ram and N. Ram. Despite the fact that a reviewer Ravi Shankar of Laxman’s autobiography for the India Today magazine (Oct.5, 1998) was unimpressed by it, it impressed me much about Laxman’s story-telling skill, akin to that of his respected elder sibling, R.K. Narayan. Ravi Shankar’s dyspeptic inference was “essentially the book is an autobiography in self-defence, of the journey of a small town boy who came to the big city in pursuit of his passion – drawing. Of course, Laxman didn’t tell all details of his life, especially the failed first marriage to elite Bharata-Natyam dancer and actress Kamala Lakshman, who is now 80. In page 16, there is a passing reference in one sentence within parenthesis, which states, “(Later in life I married one of the nieces, Kamala.)” Subsequently Laxman married again, and his second wife’s name was also Kamala. This marriage lasted until his death.

On creating his alter ego ‘The Common Man’, Laxman had written the following: “The nightmare of a political cartoonist is the deadline which haunts every newspaper office. He has to read the papers, analyse events, wait for his satirical idea to dawn, complete the cartoon and meet the deadline so that his efforts appear in the morning edition.

On creating his alter ego ‘The Common Man’, Laxman had written the following: “The nightmare of a political cartoonist is the deadline which haunts every newspaper office. He has to read the papers, analyse events, wait for his satirical idea to dawn, complete the cartoon and meet the deadline so that his efforts appear in the morning edition.

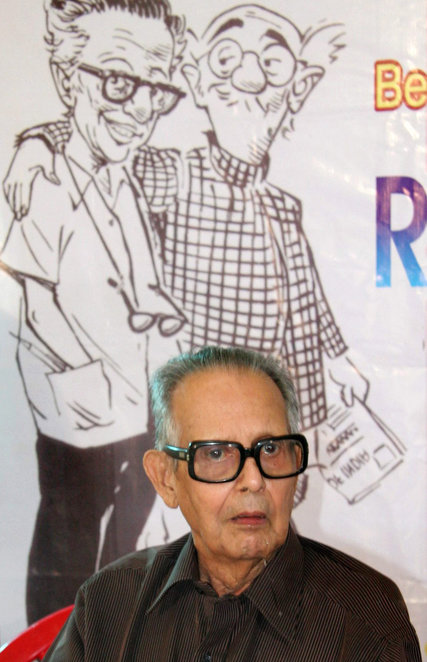

I had not only to show the ministers who mooted policies or programmes, I also had to convey the reactions of those who were affected by government programmes – namelessly the masses. Each time I had to show in my cartoon not one Indian citizen but several: Tamils, Gujaratis, Bengalis, Punjabis, Maharashtrians. All were Indians of course but their looks, habits, dress varied vastly. I had to draw quite a crowd to indicate the common citizen. Sometimes when I had to work against time because I wasn’t inspired early enough in the day, I used to reduce the number of these common citizens. Gradually the reader came to know that the crowd, however small, represented the people. I eliminated a few more in the course of time. Finally there was only one left. He was bald and bespectacled, his bulbous nose propped above a bristly moustache. He had a permanently bewildered look and was dressed in a dhoti and a checked coat. This man finally minimized my deadline agonies and took over the strenuous task of representing the mute millions of the country.”

I also enjoyed reading Laxman’s humorous story telling of how some decades ago, the Indian bureaucracy dealt with Playboy magazine, which was sent to him by his American friend. Here is an excerpt; I have omitted an interlude about his trip to Rajasthan with dots, and continue his trouble with the Indian postal authority, which lasted for an year.

I also enjoyed reading Laxman’s humorous story telling of how some decades ago, the Indian bureaucracy dealt with Playboy magazine, which was sent to him by his American friend. Here is an excerpt; I have omitted an interlude about his trip to Rajasthan with dots, and continue his trouble with the Indian postal authority, which lasted for an year.

“…A letter arrived from the postal apprising department. It informed me that I had been held guilty of importing obscene literature into the country in violation of the Sea Customs Act of 1892, Section II. I was further told that the offensive material had been impounded and I was ordered to explain why I should not be prosecuted!

As I read it an ice-cold chill went down my spine! I later learnt that a well-meaning American friend, who was posted at the US consulate in Bombay years earlier, had sent me the bumper issue of Playboy magazine as a Christmas gift.

I began to run around desperately looking for trusted friends who would help me out of this embarrassing situation. But instead of helping me, after reading the letter quizzically as if I had been caught in some naughty act, they asked in a confiding tone if I would let them have a look at the forbidden magazine!

I spent sleepless nights searching for a solution to this inadvertent mess. Not finding any, I decided in despair to ask the postal authority itself for a way out. An officer of the department suggested that if I was really innocent, I should say so in a letter, plead total ignorance of the matter and disown any knowledge of the sender, my American friend! I promptly drafted the letter according to his instructions, and handed it over to him. Days and weeks passed, but there was no response from the postal department. I had expected an immediate reply pronouncing me innocent and acquitting me honorably.

Gradually with the passing of time my anxiety wore off. I even began to regale groups of friends at parties with this story, which kept them roaring with laughter…

Among them [pile of letters that have accumulated] was a sickly-brown envelope bearing a Government of India stamp. My heart missed a beat at the sight of correspondence from the postal department. I did not realize that I was still held guilty of impunities committed under the Sea Customs Act; I had supposedly imported obscene literature into the country over a year ago!

I hurriedly tore open the envelope and read the letter, skimming over the chilling words, anxious to get to the vital point where my punishment was pronounced. [Note by Sachi: Dots which follows, are as in the original.] ‘…penal…action…Playboy…objectionable goods…Customs Act…1892…’ Just as I was about to resign myself to being jailed as an obscene-minded freak in a community of people of high morals, I saw typed faintly at the very bottom of the letter, ‘Your explanation has been accepted and the offending material has been seized absolutely.’ Thereby meaning that I had been honorably acquitted!”

I enjoyed reading this story by Laxman, because I also suffered the same fate, not in India, but in Japan in 1991. In Laxman’s case, the Playboy issue was a gift from his US consulate American friend. In my case, during my previous sojourn in Philadelphia, I had subscribed to Playboy for two years, and I had packed these issues with all my collection of books, scientific journals and magazines (quite a range, Time, Newsweek, Economist, National Geographic, Atlantic Monthly etc. etc.), amounting to a total of 70 boxes. After I arrived in Osaka, within four weeks I received a similar notice from Kobe Customs Office in Japanese, requesting my visit to their office at such and such a date with certifiable evidence to convince them, why I had to bring Playboy magazine into Japan. The notice came, because in random checking of my boxes, Customs folks had found a couple of personal subscription copies of Playboy. Unwilling to go through the formality and plead my case in defense of Hugh Hefner’s philosophy, in an apologetic tone, I requested the officials to discard those ‘offending ‘issues to Japanese morality, in whatever way they wish so. Thus, bureaucracy in Japan and India is the same. Only difference was that, in Japan the issue was taken care of within a week. But, for Laxman, it took one year!

There is no doubt that Laxman’s creations (cartoons and writings) will delight many in the future as well. His was indeed, a unique life.

Sources

R.K. Laxman: The Tunnel of Time – An Autobiography, Viking -Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, New Delhi, 1998.

Susan Ram & N. Ram: R.K. Narayan – The Early Years: 1906-1945, Viking -Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, New Delhi, 1996. [for the family photo of Krishnaswami Iyer clan, circa 1925-26]

—————-

R.K. Laxman in an undated photo. His character, the Common Man, is pictured behind him in a checkered shirt.CreditPress Trust of India, via Associated Press

His death was confirmed by his son, Srinivas.

The Common Man was the star of “You Said It,” which Mr. Laxman created in 1951. Wearing a dhoti and a checkered coat, with a bushy mustache, a few wisps of hair, a bulbous nose on which perched a pair of glasses, and thick eyebrows that were permanently raised, the Common Man observed the contradictions, ironies and paradoxes of the world around him with a bewildered look but without ever uttering a word.

Political hypocrisy was Mr. Laxman’s favorite target. The Indian National Congress Party bore the brunt of his satire over the years because it was in power longer than any other party, but he spared no leader, however powerful.

“I am grateful to my leaders for keeping my profession flourishing,” he once remarked. “Alarmingly, the politicians walk, talk and behave as though they were modeling perpetually for the cartoonist.”

Rasipuram Krishnaswamy Iyer Laxman was born in the state of Mysore on Oct. 24, 1921. His father was a headmaster, his mother a homemaker. He had a sister and six brothers, one of whom, R. K. Narayan, went on to become a leading novelist and short-story writer.

“I do not remember wanting to do anything else except draw,” Mr. Laxman wrote in his autobiography, “The Tunnel of Time” (1998). He drew with chalk on the floors, walls and doors of his house and, when he learned to wield a pen and pencil, added beards, mustaches and shaggy eyebrows to photographs and sketches in books and magazines. At school, he drew caricatures of his teachers, who, instead of chiding him, encouraged his talent.

While studying at the University of Mysore, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in philosophy, political science and economics, he began contributing political cartoons to various publications. His first full-time job was with The Free Press Journal in Mumbai. Six months later he joinedThe Times of India.

His marriage to the dancer and actress Kumari Kamala ended in divorce. In addition to his son, his survivors include his wife, Kamala Laxman, a writer of children’s stories.

Mr. Laxman also wrote short stories, essays and travel pieces, as well as the novels “The Hotel Riviera” (1988) and “The Messenger” (1993) and his autobiography.

In 2005, he received the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian award. Among his other honors is a statue of the Common Man in Pune.