by A.O.Scott, ‘The New York Times,’ May 5, 2016

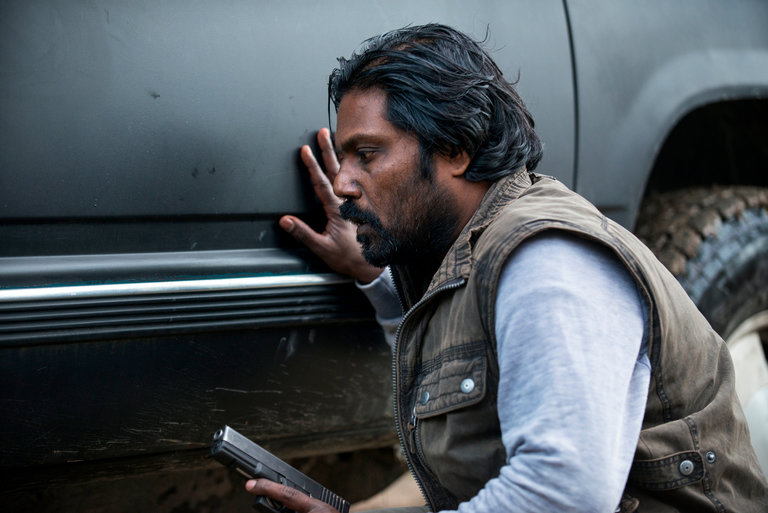

Jesuthasan Antonythasan in “Dheepan.” CreditPaul Arnaud/Sundance Selects

But while it certainly belongs to a long tradition of muscular, topical screen entertainment — its DNA bears traces of pre- and post-dictatorship Latin American cinema, of the early films of Costa-Gavras, of Old and New Hollywood agitprop — “Dheepan” has more than headlines on its mind. Its title character is in determined flight from political commitment and the violence that accompanies it, and the film is sympathetic to his aspirations. A former Sri Lankan Tamil militant who, it’s suggested, has both witnessed and participated in atrocities, he comes to France in search of peace and quiet and a chance to forget.

While this man’s previous life was defined by ideology and nationality, his particular identity crisis is a starkly existential matter, a question of character and action. Dheepan is not his real name. (He is played by an actual former Tamil Tigers fighter named Antonythasan Jesuthasan.) Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan) and Illayaal (Claudine Vinasithamby), his ostensible wife and daughter, are no kin of his. The people whose passports they carry were killed in Sri Lanka’s civil war, as were Illayaal’s parents and Dheepan’s children.

They have, in effect, borrowed a new life from the dead, and the transaction is mostly successful. They are able to leave the refugee camp where they meet and fly to France (though Yalini would prefer to go to England, where she has relatives). After a spell in a crowded dormitory in Paris, during which Dheepan earns money selling trinkets and batteries on the street, the three are granted asylum, thanks to the intervention of a sympathetic interpreter and the benign haplessness of the French state.

Relocated to a squalid block of high-rises with a mockingly pastoral name, they do their best to assimilate. Illayaal enrolls in school. Yalini finds work taking care of a disabled man. Though she isn’t Muslim, she wears a head scarf to blend in with other immigrants. Dheepan takes over as superintendent, keeping his head down as he cleans up after the gangs of drug dealers who periodically occupy one of the buildings. No one in the neighborhood knows anything about Sri Lanka or its troubles. Local turf battles are of greater concern.

For their part, the newcomers are preoccupied by household matters. Yalini doesn’t have much natural maternal feeling, and Illayaal feels no particular attachment to her make-believe mother. Yalini develops something of a crush on Brahim (Vincent Rottiers), a blue-eyed ex-convict who lives in the apartment where she works. Illayaal gets in trouble for fighting at school. Their three-way domestic charade is constantly in danger of coming undone in ways that are both comical and heartbreaking.

Some elements of Mr. Audiard’s style — off-center close-ups, restless camera movements, natural light and naturalistic sound — align him with the strain of austere, somber, ethically engaged European realism that often dominates the film festival circuit. His use of nonprofessional actors in “Dheepan” underlines that connection. But he also possesses a romantic streak and a populist soul. He makes popcorn movies disguised as art films, and vice versa. “Dheepan” is a bit like a Liam Neeson revenge-dad action thriller directed by the Dardenne brothers. I mean that in the best possible way.

VideoTrailer: ‘Dheepan’

There are directors who use individual stories to illuminate social conditions. Mr. Audiard does the opposite. Poverty, incarceration, the lives of immigrants and the demoralization of the French working class interest him insofar as they throw into relief the incandescent passions of specific anguished, idiosyncratic souls. His breakthrough film was “The Beat That My Heart Skipped,” a breakneck remake of James Toback’s “Fingers,” a pulpy crime story about a gifted musician in free fall. He followed it with “A Prophet” and “Rust and Bone,” a prison drama and a boxing picture that fused raw verisimilitude with something close to Hollywood fantasy. Those movies did not so much transcend the conventions of their genres as fulfill them with unusual intensity and conviction.

“Dheepan” works the same way. Mr. Jesuthasan, watchful and diffident behind a scruffy beard and a drooping lock of hair, has the taciturn charisma of a Hollywood gunslinger. And the movie in which he finds himself is, in some ways, a western. Or rather, it generates suspense by treading the boundary between two familiar narratives. Sometimes, it seems to be the story of a man trying to get out of a bad old life and being pulled back in. At other moments, you see hints of another familiar tale, the one about the man who has seen and done terrible things who stays out of trouble until he’s pushed too far.

Who is Dheepan, really? How decent? How damaged? How brave? And what kind of movie is “Dheepan”? These are not really separate questions. The answers reveal that the Cannes jury last May was looking for the same thing that so many less eminent moviegoers seek out in frightening times: a rousing fable with a credible hero.

“Dheepan” is not rated. It is in French, with English subtitles. Running time: 1 hour 49 minutes.