by Charles Sarvan, ‘Colombo Telegraph,’ August 25, 2016

This bilingual anthology of fifty poems is by the very nature of its subject (ethnic conflict) political, and yet it would be inaccurate and unfortunate to describe the volume as a political work. It is about the experience of politics: politics as experienced not by the makers of History but by those who endure it; politics not as an abstraction but as something personally felt by ordinary, sentient, human individuals. As several of these poems attest, whether we are interested or not in politics, it affects us. Indeed, tragically, often the victims of politics are the poor and the innocent; those with no knowledge of or interest in politics. I suggest that poets do not go searching for a theme: the subject chooses and compels them through personal experience. And “experience” here includes what the poet has seen, been told or read. ‘Tamil Poems’ does not mean poems by Eelam (see Endnote) poets only, and there are several works by Indian Tamil poets. Many chose to write under a nom de plume.

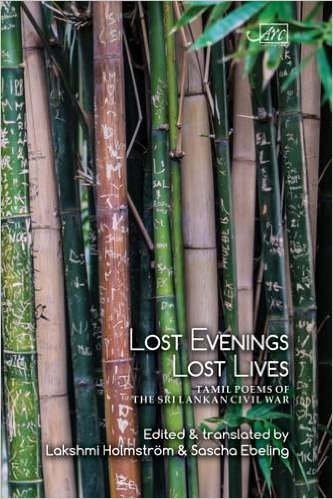

Lost Evenings, Lost Lives: Tamil Poems of the Sri Lankan Civil War -edited, translated and introduced by Lakshmi Holmstrom & Sascha Ebeling, UK, 2016.

If of the three traditional genres of Literature (Poetry, Drama, Fiction), Poetry is the most literary, it is also the most difficult to translate. Apart from other qualities poetry, associated with song, is mnemonic: we remember lines from poetry and song but rarely from prose. In translation (particularly when, as with the present collection, it is into another language that is completely different) inevitably much is lost. And it is not only musicality; cadence and rhythm, but cultural connotation. Literature emerges from, and in turn reflects, a specific way of life, a culture; when translated (trans-ported) into a foreign language and culture, rich nuances of significance can be lost. (In Shakespeare’s comedy, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when a character is turned into an ass, it’s exclaimed: “Thou art translated!”)

While a poem must stand on its own, background information can throw a different light, enhance appreciation. For example, in Nuhman’s ironic poem, ‘Buddha murdered’ (p. 25), the Buddha and his teaching have to be obliterated in order to burn down the Jaffna Library. On 1 June 1981, the Library which housed well over 90,000 works, one of the biggest in Asia, was destroyed including irreplaceable ancient manuscripts and scrolls. Similarly, Rashmy’s ‘The inscription of defeat’ (pp. 129-131) requires some knowledge of the history of the ethnic conflict, and of the LTTE leader. However,Lost Evenings, dealing primarily with violence and its impact – death and destruction; sorrow, pain of body and soul – attempts to transcend specificity and be universally comprehensible. It must be admitted that, as George Orwell wrote in his essay ‘Writers and Leviathan’ (1948), though we have “an awareness of the enormous injustice and misery of the world”, our response to literature can be coloured by loyalties which are non-literary.

The translators give a brief outline of events during the course of nearly thirty years of war: the savage 1983 pogrom, “the brutal intervention of the Indian Peace Keeping Force”, the increasing violence of the Tamil Tigers, and so to “the last terrible months of war” (p. 9). The poems are given in chronological order of publication and so parallel; arise from, and reflect, this history.

The irruption of brutality destroys what was once normality in Nuhman’s poem, ‘Last evening, this morning’ (pp. 17-19). Last evening, we popped into a bookshop, idly watched the crowds at the bus terminal, took in a film and then cycled home. This morning, bullets pierce bodies, the terminal is deserted, the market shattered.

And this was how

we lost our evenings

we lost this life.

It’s when we fall ill that we realize how wonderful it is to be free from pain and disability – a normality otherwise taken for granted. And so it is that when violence irrupts into an otherwise placid pattern of life. (I recall many years ago being asked in Jaffna by a man in genuine puzzlement: “All we want is to be allowed to lead our lives as we want. Sir, why don’t they leave us alone?” He thought it was a simple wish and, therefore, a fair question.) Jesurasa’s poem, ‘Under New Shoes’ is a ‘meditation’ based on Jaffna’s old Dutch fort. Three hundred years have passed since the imperialist, occupying, Dutch left; colour (now not white) and language (now not Dutch) have changed but for Tamils “the same rule of oppression” (p. 21) continues.

The compulsion to communicate with a loved one makes the persona of Urvasi’s poem, ‘Do you understand?’ (pp. 29-31) write a letter though there isn’t an address to send it to. (A poignant work, it recalls Ezra Pound’s beautiful rendering of the Chinese poem, ‘The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter’, available on Google.) Urvasi’s poetic persona includes in her letter what one could call home details: the jasmine is in bloom; the small puppy runs in circles, its tail raised; I dust your books. But a different reality (menace) throbs beneath the lines: they haven’t come to “interrogate” me – as yet!

‘I Could Forget All This’ by Cheran (pp. 33-4), a post-1983 poem, remembers ghastly sights such as a thigh-bone protruding from an upturned, burnt-out car; a socket empty of its eye, and a pregnant (Sinhalese) woman carrying off a cradle from a burning Tamil house. One thinks of what has been described as the shortest story ever written in English. It consists of six words: “For sale, baby shoes. Never worn.” (The story is attributed, though without evidence, to Hemingway.) Cheran concludes with a powerful use of symbolism. But

How shall I forget the broken shards

and the scattered rice

lying parched upon the earth?

A related poem is ‘Oppressed by Nights of War’ by Sivaramani (pp. 45-6) showing what happens to children in a time of protracted and “total” war: children, with their childhood destroyed. Biographical information heightens our response to Captain Vanathi’s ‘My Unwritten Poem’, a work that repeatedly urges the addressee to complete what she couldn’t accomplish. Vanathi was killed in action shortly afterwards, and this is her last poem. The year is 1991, and there is still the belief that all their suffering and sacrifice will not be in vain: As you walk freely in an independent Tamileelam, I and the thousands of other martyrs will smile with joy (p. 57): her poem will then have been written. Metaphorically, freedom is the poem that must be ‘written’ (achieved). It is indeed very strange, to read these lines in the present context.

The editorial note to Aazhiyaal’s poem, ‘Mannamperis’, explains that Tamil Koneswari Selvakumar was gang-raped by soldiers who then blew her to bits by exploding a grenade in her vagina (p. 75). But the poem, broadening outward – hence the plural Mannamperis – encompasses other instances of “man’s inhumanity to man”; more particularly, man’s inhumanity to women. During what in Sri Lanka is known as the Insurgency (the violent uprising of Left-leaning young men and women against the government) Padmini Mannamperi, a Sinhalese beauty-queen, was raped and killed by members of the Sri Lankan army (April 1971). The editorial note does not elaborate that, in an avowedly Buddhist and conservative country, Padmini was stripped naked and forced to walk down the street; that she was buried even before she was dead. One thinks, for example, of William McGowan’s Only Man Is Vile: The Tragedy of Sri Lanka (New York, 1992). It may be added that, whatever the sins and crimes of the Tamil Tigers (and they were several and grievous; destructive and, as History shows, finally fatal) I have not read of them indulging in rape or in the sexual humiliation of women. On the contrary, women seem to have enjoyed an unprecedented degree of emancipation; of equality. See for example:

The theme of exile finds expression in poems such as ‘The Lizard’s Lament’ by Solaikkili (pp. 67-69); ‘Identity’ by Aazhiyal (p. 99); ‘Goodbye Mother’ by Jayapalan (pp. 105-107) and in ‘Photographs of Children, Women, Men’ by Cheran (pp. 149-151). In the last mentioned poem, documentation is demanded of the refugees but all they carry are “burning tears”, and memories of murder and ethnic cleansing. Estrangement, to a greater or lesser degree, awaits the first-generation refugee. As Doris Lessing wrote, once you leave your first home, you have left all homes forever.

But to leave behind the one room

where you have lived all your life…

that is tragedy.

(Solaikkilli, ‘The Lizard’s Lament’, p. 69)

2009 marks the year when the Tigers were totally annihilated, and the poems following reflect this reality. Indian poet Ravikumar in ‘There Was a Time Like That’ (pp. 119-121), using the refrain “There was once a time”, reflects on a time when things were very different, both in Sri Lanka and in Tamil Nadu. Latha in ‘Empty Days’ (p. 147) writes that “the last little fragment of land that was ours” is lost; our people and their dreams destroyed. There is not a sign that they ever existed. The persona in Sharmila Seyyid’s ‘Keys to an Empty House’ (pp. 143-5) has only her memories and the rusting keys to her father’s house: the little house itself has been totally destroyed. But though the triumphant enemy celebrate; dance and mock “our overflowing tears” (Cheran, ‘Forest Healing’, p. 133), the father in Jesurasa’s poem, ‘The Time Remaining’ (p. 123), comforts his son: Life has destroyed our dreams; your path forward may now seem blocked but your time willcome: does he mean in another country?

To go on but now leave it to readers to come to terms, each in her own different and differing way, with these poems. After all, a reviewer must gesture towards, and then step aside: s/he must not stand between the reader and the text. That would defeat the purpose of a review. To learn the ‘facts’ of the 30-year conflict, one turns to history books and articles, boring or interesting, biased or objective. But if one wants to gain something of an insight into that experience, one turns to Literature.

If I may conclude on a personal note, I never met Lakshmi Holmstrom but we corresponded; I considered her a friend, and write this introduction with deep regret at her passing.

Endnote

The Editors’ clarification, bottom of page 109: “Eelam is the name in Tamil for the island of Ceylon, or Sri Lanka. This term has been in use since the classical era of the second century AD.” More recently, the term has been used “specifically to define a particular territory, the traditional homeland of the Tamils”.