by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 28, 2014

Costs of Film Production in 1950s

Historians of Indian film, Barnow and Krishnaswamy had included the currency conversion rates, as follows: For years 1949 to 1963, one American dollar equaled 5 Indian rupees. Thus, 200,000 to 2,000,000 rupees (the range cost of production of a film in India in 1950s) equaled $40,000 – $400,000. Satyajit Ray, India’s prominent auteur director, had stated in his memoirs, that the budget cost for his first movie Pather Panchali (aka, Song of the Road, 1955) was only 70,000 rupees (~$14,000). For his second movie in the Apu trilogy, Aparajito (aka, The Unvanquished, 1956), the budget was marginally increased to 106,000 rupees (~$21,000).

For comparison, I provide the comparative budget figures for five of Hollywood’s hit movies in 1950s in chronological order, as provided by van Gelder (1990).

Singin’ in the Rain (1952), directed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, and starring Gene Kelly, Donald O’Connor, Debbie Reynolds and Cyd Charrise. Produced by Arthur Freed. $2,500,000.

Rebel Without a Cause (1955), directed by Nicholas Ray, and starring James Dean, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo. Produced by David Weisbart. $600,000.

Some Like It Hot (1959), directed by Billy Wilder, and starring Jack Lemmon, Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, Joe E.Brown and George Raft. Produced by Billy Wilder. $3,000,000.

Psycho (1960), directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and starring Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, Martin Balsam and John Gavin. Produced by Alfred Hitchcock. $800,000.

The Magnificent Seven (1960), directed by John Sturges, and starring Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Eli Wallach, Robert Vaughn, James Coburn and Charles Bronson. Produced by John Sturges. $2,500,000.

The range of production costs for these five movies were $600,000 – 3,000,000, all had established stars. Compared to this range, the Guinness Movie Facts & Feats (1991) indicate that the average Hollywood budget for a feature film in 1955 was $900,000 and in 1960 was $1,000,000. As is visible, even the highly successful ‘low-budget’ Hollywood movies of 1950s (Rebel Without a Cause and Psycho) had a higher production budget than that of a Tamil movie of that era. Their world-wide appeal for entertainment was wider than the range Indian Tamil movies could have. Then, international market for Indian Tamil movies was limited to only Ceylon, Malaysia and Singapore, where a sizeable Tamil-speaking population was residing.

In mid 1950s, MGR would decide to produce, direct and act in his own movie ‘Nadodi Mannan’ (The Vagabond King) for which he’d opt to spend a fortune and test his ‘sex appeal’ and ‘staying power’ as a marquee actor in Tamil cinema. The budget for this production was recorded at the highest end of the film production range in India. More about this venture will appear later.

Sexuality and Ménage a Trois life in 1950s

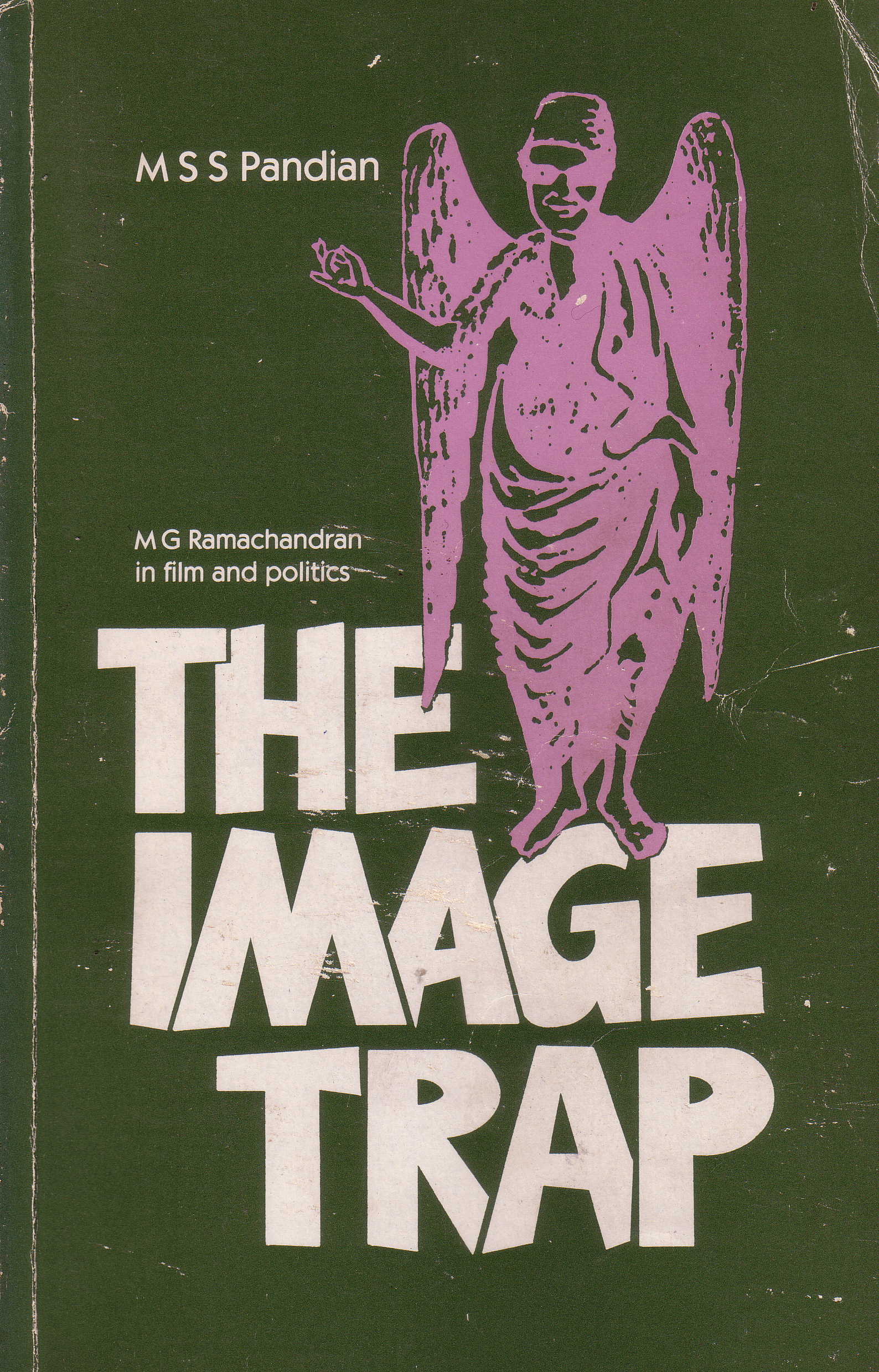

M.S.S.Pandian, one of the foremost critics of MGR’s movie and political careers, had tackled the issue of sexuality and ‘Menage a Trois’ of MGR, in his 1992 tract ‘The Image Trap’. To discuss vital theme, readers should be presented first with Pandian’s views, which I do first, citing his text.

“The repressed sexuality of the Tamil woman finds its momentary and unreal liberation in observing these sequences.” One may query, what are these ‘sexy’ sequences, Pandian had bothered to find? Pandian identifies,

“short-sleeved shirts, bare chest, rippling muscles and tight fitting clothes – MGR on the screen revels in his physicality and, in this context, a certain auto-eroticism communicates itself most effectively to female viewers.” Then, Pandian identified ‘at least three points’ which influence the sexual ‘freedom’ of the ‘female audience’. These are, to quote Pandian’s words,

“First, in a society where female voyeurism is censored as culturally unacceptable, the darkened atmosphere of the cinema hall is perhaps one of the very few places where women can indulge in voyeurism. Thus, the flickering images on the screen gain an added relevance for women spectators.”

“Secondly, by attributing desire to the heroine and at the same time distancing the hero from desire, these films assert MGR’s masculinity. This notion of the ‘distant’ hero also proves effective in deferring female sexual gratification and, thereby, definite patriarchal limits are set to this ‘free release’ of female sexuality.”

“Thirdly, MGR being represented on the screen as an idealized ‘object’ of female desire does, at another level, turn him into an ego-ideal for the male audience themselves.”

My simple criticism for this sort of selective, cherry-picking analysis by Pandian is that he had been making a mountain out of a mole hill, without due control samples of MGR’s contemporary heroes from Tamil cinema. For instance, in expanding his second point (stated above), Pandian also had included the following sentence. “It is important to note here that in several of MGR films more than one women desires and pursues the hero and, unlike the usual Tamil films, the hero does not marry in the course of the film but only at the end, that is, once his ‘other’ more important worldly/manly duties are performed.” (p.83) Opposed to this line, many examples do exist in MGR movies that in the story plot, his character is married to only one woman at the beginning or in the first half of the film, and not at the end. The best examples are, Koondu Kili (The Caged Parrot, 1954; the only movie in which he starred with Sivaji Ganesan), Maha Devi (The Great Devi, 1957; the first movie he starred with ranking Southern star Savitri), Thai Magalukku Kattiya Thali (Thali tied by mother to her daughter, 1959; story plot from C.N.Annadurai). In fact, few pages later, Pandian had covered the story plot of Maha Devi film in detail (p.89), thus contradicting his own view.

Another specific issue which Pandian picked up was that in his movies, MGR impressed his world-view on siding with the rural folks in preference to that of uppity behavior of educated urban women. In Pandian’s words, “Interestingly, the woman who is tamed by the hero [MGR, that is] is normally urban, educated and from the upper class, indulging in a bit of English on and off. In the dichotomized social universe of MGR films, this helps the hero not only to affirm male domination, but also to play upon the rural-urban divide and to stamp the countryside with a certain authenticity and constitute it as a repository of culture.”

So what? If in a population of 1.21 billion (2011 census), 7 out of every 10 Indians live in villages, and if easily accessible education (via entertainment and songs) for rural folks is one of the pillars of MGR’s policy in his movies, then one cannot find fault with this approach of MGR. The recent statistics on Indian population living in villages is available in infographic form at the Hindu (Chennai) website. Pandian had conveniently ignored MGR’s other vital focus of his movie characters; (1) no physical or mental violence against women, and (2) no indulgence in smoking or alcoholic drinks. Admittedly, this self-adherence did restrict the roles MGR chose to play, but he was more than satisfied with his choice and was successful in it for almost 30 years as a hero.

MGR’s Life with More than One Woman

Additionally, Pandian’s peeve on MGR’s successful career was that he was a hypocrite. This is because, while MGR’s movies preached and valorized (1) ideal family values and chastitity for woman, (2) monogamous family, in his real life MGR failed to practice such values. In Pandian’s words, “MGR’s ‘personal’ life was quite contradictory to the monogamous familial norms which he time and again preached on the screen. In fact, his real life would, would, within the cultural codes of Tamil society, meet all the requirements of a notorious home-breaker. First of all, he married thrice and was living with his third wife, V.N. Janaki, while his second wife was still alive. Secondly, he married his third wife while her earlier husband was still alive.”

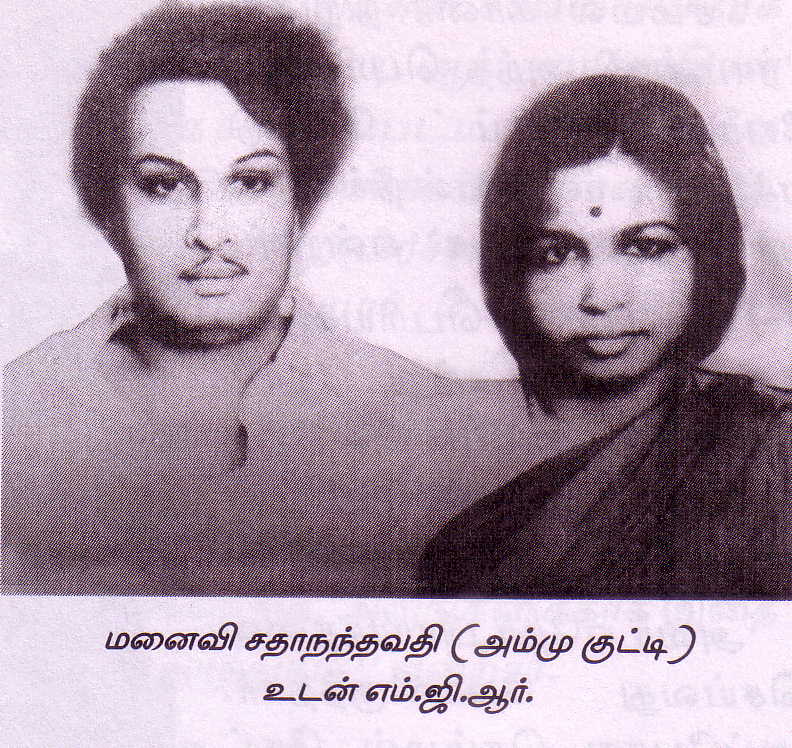

I think this is the appropriate juncture to disentangle and discuss MGR’s marriages since 1942. It is true that MGR married three times. There was nothing wrong that he married second time in 1942 at the age of 25, following the premature death of his first wife Bhargavi (Thangamani). It was his mother Sathyabama who chose his first and second wives from Kerala state for him, as previously mentioned in Part 6 of this series. MGR’s second wife was Sadhanandavathi. In his autobiographical memoirs, MGR had described amply in early 1972, (1) with unusual openness, his marital life with Sadhanandavathi from 1942 until her death in 1962; (2) his relationship with actress V.N. Janaki – how it began in late 1940s and how he led a ménage a trois life with her, with the consent of his legally married wife during the 1950s.

I’ll rely on MGR’s own descriptions and provide English translation below. One should note that among the four books in English that had appeared, as I had indicated previously in part 7 of this series, only Pandian includes references to MGR’s serialized autobiography. This indicates that Pandian was fully aware of the specific details of MGR’s married life, as the movie star had described. But, to substantiate his argument, Pandian had ignored the vital details on why MGR led the ménage a trois life in 1950s. Furthermore, Pandian also had ignored the situation faced by actress V.N. Janaki in her previous relationship with her then husband Ganapathy Bhat. In my understanding, MGR identifies this guy courtesously as ‘a sort of guardian’ to her.

Heroine Actress V.N. Janaki (1923-1996)

It becomes important to deduce, when and where this Janaki- Bhat relationship began and how it detached and deteriorated eventually to the satisfaction of Janaki, after she met MGR. In attempting to portray MGR as a ‘notorious home breaker’, Pandian had ignored the sentiments of Janaki, who had opted to spend the rest of her life with MGR since 1950, at the adult age of 27. Janaki’s date of birth is Nov.30, 1923 and she died on May 19, 1996, at the age of 72. As the three principals (MGR, Janaki and Ganapathy Bhat) had died, the only living link currently is J. Surendran, the son of Bhat – Janaki union.

I checked the age background of Surendran, from newspaper reports. It was revealed in a write up on Feb.1, 2004 by P.C.Vinoj Kumar, when he had a copyright law suit case about MGR’s autobiography at the Madras High Court, that he was 65 years. This makes Surendran’s current age as 75 years, and his birth year can be assumed as 1939. This suggests that Janaki would have given birth to him, when she was only 16 – as a minor. When Janaki got married to Ganapathy Bhat, whether she had parental consent is a moot point. This corroborates with the view point that MGR described the ‘individual’ who gave trouble to him and Janaki was ‘a person like guardian’. It can be assumed that at that age, she wouldn’t have entered the cinema field, and Bhat took on the role of ‘guardian’ for Janaki, when she was a minor. It is plausible to infer that, after 10 years or so, the relationship between Bhat and Janaki might have suffered badly for whatever reason known only to themselves, and Janaki was looking for ‘exit’ and MGR offered his hands. In the meantime, circumstances and luck had favored Janaki, to become one of the leading heroines Tamil movies by 1948.

In his autobiography, MGR had acknowledged the following facts. (1) He first saw Janaki’s face in the movie, Thiyagi (The Donor, released in August 1947). And it strongly reminded him of his late first wife, Bhargavi. (2) Janaki had higher earnings from movie roles in late 1940s, compared to him. (3) In a court case to detach herself from the tentacles of her ‘guardian’, then prominent Tamil movie personalities K. Subramaniam (director), S.S. Vasan (producer/director) and S.D. Subbulakshmi ( heroine) either supported Janaki or offered evidence on behalf of her. (4) Though she had higher earnings from movie roles compared to him, Janaki was more than willing to quit acting and continue her life in a legally unsanctioned role as a ‘partner’ [‘thunaivi’ is the Tamil word used] of MGR, and she did so to prove her love and alliance to MGR.

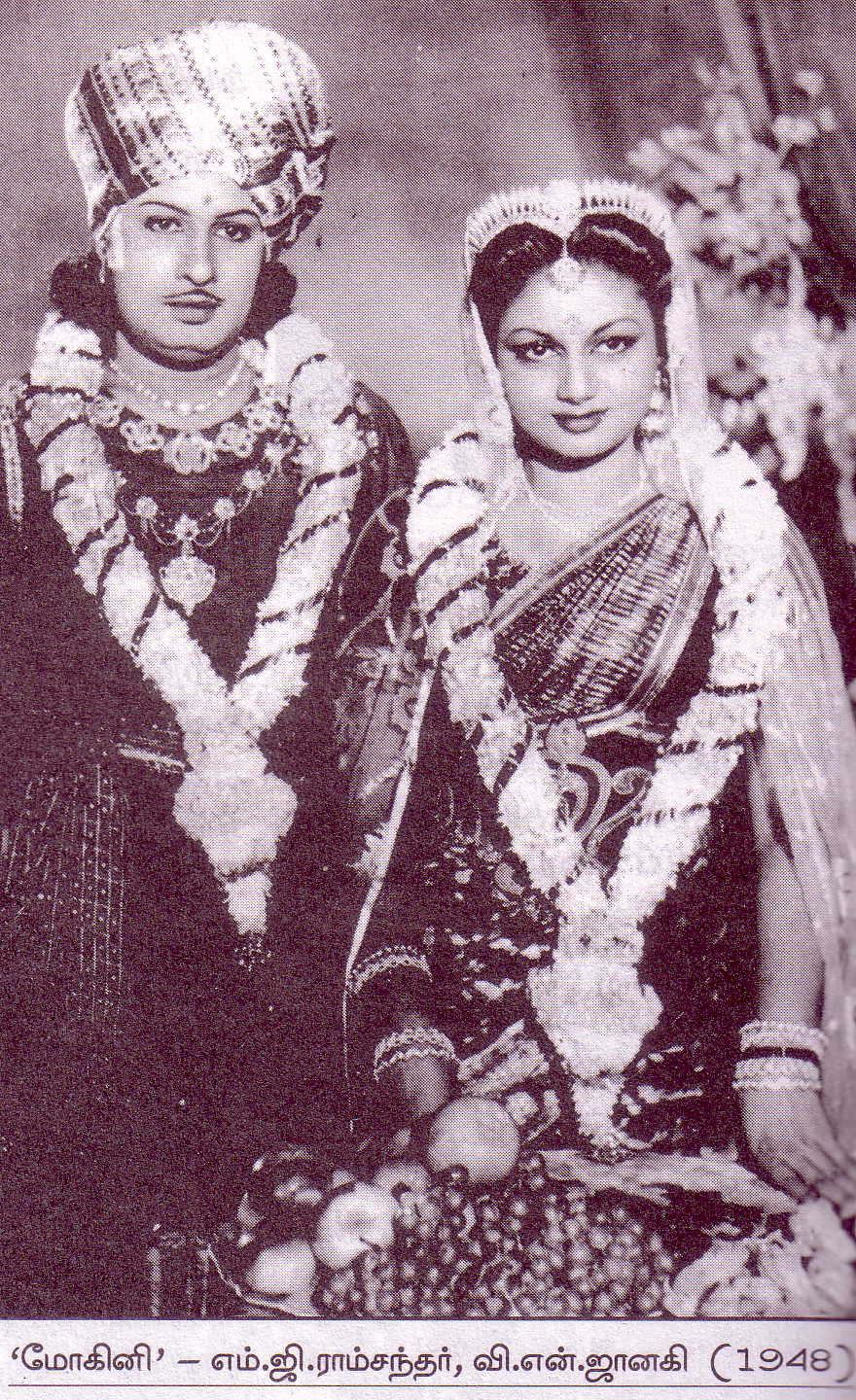

Six of the notable movies V.N. Janaki starred in late 1940s were, Ayiram Thalai Vankiya Apurva Sinthamani (1947), Thiyagi (1947), Raja Mukthi (1948), Chandralekha (1948), Mohini (1948), and Velaikari (1949). Among these, she paired with MGR in Mohini. Artistically most successful was Velaikari (The Servant Girl), a paradigm-shifter in Tamil movies, scripted by MGR’s mentor C.N. Annadurai. Popularly most successful was Chandrakekha (1948), produced by mogul S.S. Vasan, at the then most expensive cost of 3,000,000 rupees for an Indian movie. The first and third movies listed, though not featuring MGR, had MGR’s elder brother Chakrapani in star listing.

MGR’s version of his marriage with Sadhanandavathi

Though MGR did not mention the year of his marriage to Sadhanandavathi, it could be deduced circumstantially that the marriage probably took place in 1942, immediately following the death of his first wife. At that time, he was 25 years old. It could be guessed that his wife would have been younger to him. Chapters 100, 101 and 104 of MGR’s memoirs offer rich details. Reminiscing about this life 30 years later, when he was 55, one could feel the distress he had to endure in his professional circles about being issueless. There were circumstances that MGR had to endure behind-the-back gossip and ridicule in the print media about his virility and inability to produce an offspring in real life, though he projected a macho image in the screen. Here are MGR’s reminiscences in chapter 100, with the caption ‘I’m Your Wife’ – the words of Sadhanandavathi to him.

“My mother had a strong wish that I should have a child. As I was unlucky not to have one with my first wife, my mother wished that I should have one with Sadhanandavathi. While noticing that she was weak, one day my mother took her to a doctor and requested to give an injection to her to retrieve her health. The doctor had given an injection, without examining wife’s body status. The result turned out to be horrible. In reality, Sadhanandavathi had conceived. But, because of shyness and immaturity, she couldn’t express it openly. Severity of injection had caused miscarriage. How much wish my mother had about me having a child, the opposite turned out as a result. Since then, Sadhanandavathi’s health was affected badly.”

MGR continues further. “She was taken to her native village, and given ayurvedic treatment…When she returned to Chennai later, her condition had worsened… At the insistence of elder brother Chakrapani, we took her for medical consultation. Then, we received the bad news. That was, she was at the early stages of tuberculosis (TB). Lungs had been affected. In those days [circa early 1940s], TB was considered as an incurable disease and, it could be easily infected to others. It was told that, no curative drugs were available.”

About his professional status, MGR had written, “What was my financial status then? Occasionally we borrow money. No, our mother borrowed money. Almost all the small jewelry in the house (we didn’t have any ‘large’ jewelry) had been pawned. In those occasions, somehow I was offered small roles. We satisfied ourselves with the advances received for those roles. Though Sadhanandavathi and I had opportunity to enjoy life for some time, even such opportunities were mishandled by my mother and her mother.” MGR does include the conflicts his mother and mother-in-law had in the joint household, pertaining to MGR’s previous marriage and his poverty.

In the subsequent chapter 101 entitled, ‘You are lucky’ – the words of Dr. Vasudeva Rao, who treated Sadhanandavathi to him, MGR frankly described his sexual feelings briefly. He had written, “Even though doctors asserted that [she – Sadhanandavathi] is recovering well, due to scary thoughts she, me and our household folks had, we had been extremely cautious. For one or two years, though married, we two lived a life with non-conjugal demands.” MGR had mentioned four doctors who treated Sadhanandavathi, namely Dr. Vasudeva Rao, Dr. Santhosam, Dr. U. Ananda Rao and Dr. P.R.Subramaniam. Among these four, Dr. Vasudeva Rao and Dr. Santhosam (both TB specialists) had predicted only three months for his wife in 1944. Subsequently, Dr. Subramaniam (who was a general physician, and later became the family physician of MGR) treated Sadhanandavathi with injections and drugs. MGR mentions that she did receive 200 injections altogether, beginning with 2 injections per day. “Somehow with luck, Dr. Subramaniam’s treatment allowed my wife to live for 18 years since then.”, according to MGR.

Chapter 104 in MGR’s autobiography, entitled ‘Little Rest for Her Soul’ was a fascinating chapter, among all the 134 chapters. In it, MGR had revealed his thoughts openly of being an expectant father and how his hopes were dashed. The situation was described by him in chapter 101, while he was shooting ‘Marma Yogi’ movie at Coimbatore Central Studio, one night he received a telegram “Danger for Ammukutti [the pet name of his wife]. Come immediately.” He expressed his concern to Mr. M. Somasundaram, the boss of Jupitor Pictures. At that time there were no trains. The boss kindly offered his car to MGR and advised, ‘Don’t travel during night. Even though there’s a delay by two hours or so, its better to start early in the morning’. As ‘Marma Yogi’ movie was released in February 1951, one is not sure when this incident happened. MGR also didn’t identify the specific year in his recollections.

Then, in chapter 104, MGR recollects the event as follows: “Rather than the worries I had about why Sadhanandavathi had to undergo a surgery, when I learnt about the reason for that surgery, my worry did multiply manifold. How can I feel helplessness when one of my biggest wishes in my heart, and what is naturally common to any man getting shattered becoming a reality? Is it wrong to have a wish to become a father? If nature had given the verdict that one cannot become a father, then that person can be comfortable with the situation. But, when nature and deeds had proved perfectly that one can become a father, but the situation and reality was deprived beyond control, how could one feel not hurt? My situation was like that.

The nature convinced us that my wife Sadhanandavathi and I could have a child. Doctors also attested to it. First time, she conceived; but she miscarried. This time also, she conceived. But to save her life by surgery, the fetus was prevented from developing…I arrived at the hospital with these thoughts…One day she had screamed at home due to extreme stomachache. Dr. P.R. Subramaniam checked her and gave medicine for stomachache. But recurring intolerable stomachache made the doctor to invite a lady doctor for checking. Then, it became known that she had conceived. But, Dr. P.R.Subramaniam had insisted, “It cannot be. I had told MGR strongly, not to have intercourse. He wouldn’t have disobeyed. So, this cannot be pregnancy.” The X-ray revealed that the pregnancy was an ectopic one, and as the tube could burst anytime, surgery was decided to save the mother and lose the fetus…Dr. P.R. Subramaniam didn’t like to see me. He was extremely angry that though he had explained to me her health condition, I had had intercourse. He was a doctor; he did his duty. But for me, having lived more than two years without conjugal relations, I had failed in the game with Nature. Then only I realized that such a loss of mine had turned detrimental to the life of Sadhanandavathi. I had cussed my feelings, why I couldn’t tolerate for some more months…Though I could somehow convince myself, I found it difficult to convince Dr. P.R.Subramaniam, about my selfish deed. He didn’t even want to look at my face. Only after she recovered her health and returned home, Mr. P.R.Subramaniam talked to me. I expressed my heart-felt excuse. But, I asked him, ‘How long do you expect me to live like this? How do you trust that I have to live without any sexual desire and control myself?’ He did understand my situation. But, he responded, ‘To achieve a great deed, somehow we have to sacrifice something. Like this, if you wish Sadhanandavathi to live, then you have to adapt to inconveniences and setbacks.’

MGR’s autobiography re-released

Thorough the courtesy of my friend and fellow MGR biographer R. Kannan, I was informed that MGR’s autobiography ‘Naan Yean Piranthen’ [Why I was Born?] had been re-released last January in two volumes. He also took the trouble to gift me copies of two volumes, and I express my debt to him for this kindness. The publisher is Kannadhasan Pathippagam, and the publishing editor is Gandhi Kannadhasan (son of poet Kannadhasan). He had successfully negotiated the publishing rights with the current holder of copyrights, J. Surendran (the son of V.N.Janaki and Ganapathy Bhat). Part I, consisting first 63 chapters in 736 pages, is priced at 460 Indian rupees. Part II, consisting of chapters 64 to 134 from 737 to 1488 pages, is priced at 500 Indian rupees.

Sources

Film News Anandan: Sadhanaigal Padaitha Thamizh Thiraipada Varalaru [Tamil Film History and its Achievements], Sivagami Publications, Chennai, 2004 (in Tamil).

Barnouw E and Krishnaswamy S: Indian Film, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, New York, 1980.

Peter van Gelder: Off Screen On Screen – The Inside Stories of 60 Great Films, Aurum Press Ltd., London, 1990.

Vasudevan Mukunth and S. Rukmini: India lives in her (mid-sized) villages. The Hindu (Chennai), Dec.10, 2013.

M.S.S.Pandian: The Image Trap – M.G.Ramachandran in Film and Politics, Sage Publications, New Delhi, 1992.

Patrick Robertson: Guinness Movie Facts & Feats, 4th ed., Guinness Publishing Ltd, Enfield, Middlesex, 1991.

Satyajit Ray: My Years with Apu, Penguin Books, New Delhi, 1994.

Vinoj Kumar P.C.: MGR books kicks up a row.

[http://www.mid-day.com/news/nation/2004/February/75357.htm. Accessed Nov.25, 2004]