by T. Sabaratnam, May 2003

Volume 1, Chapter 3

Original index of series

Original Volume 1, Chapter 4

Chapter 4: Tamil Mood Toughens

The Federal Party Working Committee met on 11 July, 1970 at Vavuniya to consider Dr. de Silva’s message. Thanthai Chelva told the meeting the government had indicated many positive features in the new constitution and Tamil representatives should make use of that opportunity. C. Rajadurai, V. N. Navaratnam and other youths voiced their doubt. “Would it serve any purpose?” was the question they posed.

The Working Committee decided to organize a consultation with prominent Tamil persons to determine the question of participation and to identify the issues to be raised in the Constituent Assembly if they decided to participate.

![]() The consultation with prominent Tamil lawyers and elders held a week later at Saiva Mangayar Hall in Colombo decided that all Tamil parliamentarians should attend the meetings of the Constituent Assembly, participate in its deliberations, and try to obtain the Tamil demands. Summing up the conclusions of the 3-hour consultation Thanthai Chelva said:

The consultation with prominent Tamil lawyers and elders held a week later at Saiva Mangayar Hall in Colombo decided that all Tamil parliamentarians should attend the meetings of the Constituent Assembly, participate in its deliberations, and try to obtain the Tamil demands. Summing up the conclusions of the 3-hour consultation Thanthai Chelva said:

The meeting decided to ask the Tamil MPs to attend the Constituent Assembly and place before it the basic Tamil demands for a federal state structure, for adequate sharing of power between the Centre and the Regions, for parity of status for the Tamil language, that education be imparted in the mother tongue and for strong guarantee of fundamental rights together with legal remedies against infringement. An expert committee will be asked to draft and present to the Constituent Assembly a model constitution.

Members of Parliament met on the invitation of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike at Navarangahala, the Royal College auditorium, on 19 July, 1970 and decided after three days of discussion to convert themselves into a Constituent Assembly to draft, enact and operate a new constitution. Opposition Leader J R Jayewardene, Federal Party member S Kathiravetpillai and Tamil Congress member V. Anandasangaree assured the cooperation of their parties. The Steering and Subject Committee, comprising representatives of all parties was set up at the next meeting to consider the basic resolutions that would form the core structure of the constitution.

The Constitutional Committee of the Federal Party drafted a model constitution and presented it in September to the Steering and Subject Committee for its consideration. The model constitution contained seven sections of 60 articles. It provided the basic structure that could satisfy the five Tamil concerns Thanthai Chelva had indicated in his summing up at the conclusion of the consultation held at Saiva Mangayar Hall.

Section 1 of the model constitution provided for the federal structure of the state. It proposed a system comprising a central government and five regional states. The states were formed on the basis of the economy of the regions. The economically advanced western and southern provinces were grouped into one state. Coconut-growing areas of the north-western and north-central provinces were brought into another state. The tea and rubber-growing Uva, Sabaragamuva and Central Provinces were grouped into the third. The northern province and Trincomalee and Batticoloa districts of the eastern province were grouped into a North-eastern state and the Muslim majority district of Amparai was to form the South-eastern state.

Section 1 also gave a detailed power-sharing scheme for the Central Government and the states. The Central government would be run by Parliament and States by State Assemblies. Members of the State Assemblies would be directly elected by the people. They would be divided into committees, each headed by a chairman elected by the members. The chairmen of the committees would constitute the Board of Ministers and the Board of Ministers would elect the Chief Minister.

The model constitution allocated to the Central Government the following subjects: international relations, defence, law and order, police, citizenship, immigration and emigration, customs, postal and telecommunication services, ports, sea, air and rail transport, inter-state roads, electricity, irrigation, weights and measures, determination of the national policy in health and education, Central Bank and monetary policy. The rest of the powers were left to the states.

Section 4 proposed that Sinhala and Tamil would be the national languages and courts in the north and east would function in Tamil and those in the rest of the country would work in Sinhala and every citizen would have the right to communicate with the government in his mother tongue. Section 5 stated that the medium of instruction would be the mother tongue. Section 3 provided for the fundamental rights with the right to legal remedy against infringement.

The Steering and Subjects Committee, which met regularly from 4 January 1971, did not consider Federal Party’s model constitution. Instead, it considered the Basic Resolutions prepared by the government. It took up Basic Resolution No 1, which read that ‘Sri Lanka would be a free, independent, socialist republic’ on that first day. It was approved unanimously.

Basic Resolution No 2 which read; ‘The Republic of Sri Lanka shall be a unitary state’ brought the Federal Party into conflict with the government.

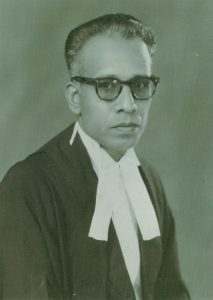

V. Dharmalingam

The Federal Party’s S. Dharmalingam moved an amendment on 16 March which said Sri Lanka should be a ‘non-sectarian federal republic’. In an impassioned plea to the Sinhala leaders, he said communal harmony was a prerequisite to national harmony and development and argued that only a federal structure that ensured the self-respect and security of the Tamil people would provide the environment for concord. Government speakers rejected that request saying that they had no mandate to draft a federal constitution.

Dharmalingam pleaded;

If you have no mandate to establish a federal constitution, please at least consider the decentralization of the administration.

He also told the Steering and Subjects Committee;

I wish to make our position very clear. Tamil people have rejected the unitary constitution from the first parliamentary election held in 1947. In addition, from 1956 they have voted for a federal constitution. Our mandate from the Tamil people is for a federal constitution.

The Basic Resolution calling for the establishment of the unitary state was passed on 27 March 1971.

Dharmalingam, an ardent socialist, was dejected. He told the Tamil press;

Today is an ominous day for Sri Lanka. The trouble with my Sinhala friends is that that they are concerned only about the Sinhala people and their interests. They fail to see the Tamil side and refuse to accommodate their interests.

Sinhala leaders declined to accommodate Tamil interests in the question of language also. The Basic Resolution about the language stated, “The official language of Sri Lanka shall be Sinhala as provided by the Official Language Act No 33 of 1956.” By this the government enshrined in the constitution the Sinhala Only law enacted by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike on 5 June 1956. The Federal Party’s request that the laws concerning the reasonable use of the Tamil language also be enshrined in the constitution was rejected.

Similarly, superior status was accorded to the Sinhala language regarding enactment of laws and in the case of the language of courts. The Basic Resolution on the language of legislation stated that all laws should be enacted in Sinhala and their Tamil translations be provided. The Federal Party’s request that that all laws be enacted in Sinhala and Tamil was rejected. The Basic Resolution concerning the language of courts made Sinhala the language of courts countrywide. The Federal Party’s plea that courts in the northern and eastern provinces be allowed to conduct their affairs in Tamil was turned down.

K. Jayakody

Federal Party’s Udupiddy MP, K. Jayakody’s, plea; “At least permit the courts in the north and east to conduct their proceedings in Sinhala and Tamil,” was not entertained.

To cap all this, Buddhism was provided a superior position, doing away with the secular aspects of the earlier constitution. The Basic Resolution on Buddhism read; “The Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place and, accordingly, it shall be the duty of the state to protect and foster Buddhism, while assuring to all religions the rights granted by section 18[1] [d].”

The constitution makers did not stop at that. They dropped the safeguards Section 29 of the Soulbury Constitution provided to the minority communities against discrimination. Section 29 (2c) prohibited Parliament from enacting laws that “confer on persons of any community or religion any privilege or advantage which is not conferred on persons of other communities or religions.” Though the courts failed to act on this safeguard when Indian Tamils were disfranchised and when Sinhala was made the official language, the Sirimao Bandaranaike government felt that its retention in the constitution would harm the Sinhala interest in the future. They also made the Parliament supreme, thus consolidating Sinhala power.

Tamils Lose Faith

The hard line taken by the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government produced a strong reaction among the Tamil people, especially the youth. Tamils lost faith in the Sinhalese. Their mood hardened. The youths resumed their campaign demanding that the Federal Party quit the Constituent Assembly. “Why are you still attending the Constituent Assembly when your requests are turned down?” they asked. The irrepressible Suntharalingam issued a statement;

We asked you not to go. We told you that you would be outvoted. You went. See what had happened? You have been outvoted. Your voice had not been heard. As we warned, you have only weakened the Tamil cause.

Amirthalingam who had been assigned by the Federal Party the task of answering Suntharalingam’s criticisms was at a loss when pressmen contacted him to get a reply. He confided on an off the record basis;

What is the answer I can give? We have been let down even by the leftists in the government. We look a set of fools in the eyes of the youths.

The Federal Party had no way out. On 21 June Thanthai Chelva announced the Federal Party’s decision to quit the Constituent Assembly. Thanthai Chelva issued the following statement;

We moved several amendments regarding the nature of the constitution, citizenship rights and other fundamental rights. All these amendments were rejected. I sought an interview with the Prime Minister with a view to arriving at a compromise to the problems which had to be settled not by a majority of votes but by mutual adjustment and agreement. Our interviews with the Prime Minister, the Minister of Constitutional Affairs and others do not appear to have produced the desired results. We are always willing to compromise for the sake of agreed settlement of the vexed question. We indicated to the Prime Minister and Minister of Constitutional Affairs the minimum rights we want embodied in the constitution. Although our discussions were cordial and our views apparently received serious consideration, yet they were not prepared to make any alteration to the Basic Resolutions as they stand.

Youths treated the Federal Party’s decision to pull out of the Constituent Assembly as their victory. They started talking openly that the path of cooperation with the Sinhala community had ended and a new confrontational approach had to be adopted. But, except for a handful, others were talking about non-violent struggle.

Lessons from Revolts

Two events that profoundly affected the Tamil youths occurred during 1971 when the Constituent Assembly was busy drawing up the constitution. The first, the JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna) insurrection happened during March – April and the second, the Bangladesh War, in December.

Tamils in general, and Tamil leaders in particular, were not concerned when the JVP insurrection broke out. They considered it a wholly Sinhala affair, a conflict involving two Sinhala factions, the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government and neglected Sinhala youths. Tamils were not directly involved.

They showed keen interest in the Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) freedom movement from the inception. They were interested in it because India got involved and fought the third Indo–Pakistan war. It resulted in the creation of a new state, Bangladesh.

Preparations for the JVP insurrection and the Bangladesh freedom struggle commenced in 1970. The basic causes for both revolutions were similar, the relative backwardness and the resulting discontent among the people In southern Sri Lanka, the rallying slogan was: To us they give coconut milk; to Colombo people cow milk. In Bangladesh, the rallying cry was the exploitation of East Pakistan by West Pakistan.

The JVP attack commenced on 5 April morning in Monaragala and Wellawaya. It was planned for the evening but the misinterpretation of a message caused confusion. The JVP leadership, which met at the Vidyodaya Sangaharamaya on 2 April decided to launch their attacks on police stations and army camps island-wide at 5 pm on the evening of 5 April. A coded telegram was sent on 4 April saying “JVP Appuhamy expired, funeral 5”. The signal for the attack was the pop song “Neela Kobeyya”, played over the state-owned radio, Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation. Leaders from Wellawaya and Moneragala started the attack on the police stations in the early morning and the government alerted the police countrywide. The police readied themselves to meet the offence. They set up defensive positions. Realizing their mistake, the JVP then advanced its attack.

Groups of 25 to 30 youths, armed with home-made petrol bombs and grenades, surrounded the police stations on all sides and attacked them. About 93 of the island’s 273 police stations in the country fell. The government evacuated many more police stations located in the most vulnerable areas.

The rebels were poorly armed, untrained and often badly led. Their major weapon was the surprise element and, once the initial attack was repulsed, the government forces regrouped and launched devastating counter attacks. The government also called out the army and appealed for international help. Many countries responded and India sent helicopters and crack paratroopers.

The armed forces struck back and within three weeks they had broken the back of the insurgents, and by the end of the year some 18,000 insurgents and their sympathizers were in prison camps. Official figures put the total killed at 5,000, while the accepted unofficial figure is around 25,000. Atrocities and summary executions were alleged, but the government denied them.

Fort Hammerheil

The widely talked about story was the midnight escapade of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike and her children who were taken to a ship anchored outside the Colombo harbour and kept there till Colombo was safe. The other story, which interested the Tamils more, was about the group that went to Jaffna to free Rohana Wijeweera and 12 others kept in custody inside Fort Hammenheil, off the Karainagar Naval base.

Tamils were also interested in the Bangladesh liberation. The partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 created two states, India and Pakistan. Most of the Muslim majority areas of undivided India went to Pakistan. These areas comprised two sections, Western Pakistan and Eastern Pakistan, separated by 1600 kilometers of Indian territory. Western Pakistan, the larger, was made up of four provinces- Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and the North Western Frontier where Pathans lived. Eastern Pakistan, was a single province, Eastern Bengal.

Eastern Pakistan was more populous than the Western wing, but political power since independence had rested with the western elite. Significant national revenues were spent to develop the West at the expense of the East. The people of the Eastern wing felt increasingly dominated and exploited by the West. Friction between the two wings surfaced.

Pakistan had undergone marked political instability and economic difficulties since its birth. Civilian political rule failed and the government was dominated by its military, which was rooted in the West. This caused considerable resentment in East Pakistan and a charismatic Bengali leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, most forcefully articulated that resentment. He formed a political party called the Awami League and demanded more autonomy for East Pakistan within the Pakistan Federation. Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s Awami League won 167 seats out of 313 National Assembly seats at the general elections held in 1970. This entitled Rehman to form the Pakistan government, but the ruling elite in West Pakistan arrested him and banned his party.

All of East Pakistan rose in revolt. President Yahya Khan sent his junior General Tikka Khan to handle the situation. He ordered a crackdown on 25 March 1971 which left thousands of Bengalis dead. The Pakistan army tried to disarm Bengali troops while strengthening itself with reinforcements airlifted from West Pakistan. Bengali officers and troops deserted the army and joined the freedom fighters.

Many of Rehman’s aides and more than 10 million Bengali refugees fled to India, where they established a provisional government. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi decided in April to help the Bengali freedom fighters, especially the Mukti Bahini, to liberate Eastern Pakistan. Mukti Bahini set up a chain of camps along Eastern Pakistan’s border, well inside the Indian territory. The Pakistani army shelled these camps, which resulted in clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces. Pakistan threatened to open a front on the west and on 3 December Indira Gandhi declared war on Pakistan.

The combined Indian-Bengali forces soon overwhelmed Pakistan’s army contingent in the East. Pakistan’s forces surrendered on 16 December 1971 and a new nation, Bangladesh, was born.

The fledgling Tamil militants looked at the JVP misadventure and the birth of Bangladesh for lessons. A former Tamil militant now living in Canada said they analysed both events in depth. They were encouraged by both. “They were vitamin tonic for all of us,” he said.

The JVP revolt, he said, boosted their confidence that they could take on the Sri Lankan government:

The JVP revolt was a moral booster. We learnt from it that the state could be taken on. Given motivation, grit, weapons and leadership the state could be effectively challenged.

He said they concluded that the JVP revolt was amateurish, their weaponry poor, their training minimal, their leadership weak, and their strategy faulty. He said:

The second lesson we learnt was that one should not take territory if it cannot be held. What JVP committed was suicide. They “liberated” large extent of territory and when the police and the army regrouped and counter attacked, they bolted. We adopted the well–tested urban guerilla warfare of hit and run based on this lesson.

Drawing lessons from the Bangladeshi war was more tricky. It was not as simple as the Federal Party leaders and their youth agitators like Mavai Senathirajah, Kasi Ananthan, Vannai Anandan and Kovai Mahesan preached.

The Federal Party congratulated Indira Gandhi on the Bangladesh victory and held a seven-party rally in Kankesanthurai on 12 January 1972 to celebrate the victory. Youth leaders told the gathering that India would do a Bangladesh operation in Sri Lanka to help the Tamils establish a separate state. But they failed to comprehend the fact that Indian troops were able to infiltrate into East Pakistan along with the different armed Bangladeshi groups, Mukti Bahini being the biggest and most organized. In addition, the Federal Party still held that their mode of struggle was the 1961-type satyagraha.

Amirthalingam was the only one who went closer to armed struggle. He was careful. He talked only in general terms. He said;

Time has come for the Tamils of this country to wage a clear-cut struggle for a totally separate state and for which they should not hesitate to gain foreign assistance. Independence cannot be bought from a shop. It has to be won through a hard struggle, if necessary a bloody struggle.

Amirthlingam also called upon the Tamil people to unite and said they should follow the example set by the people of Bangladesh.

Militants analyzed the Bangladesh war much deeper. They concluded:

India will never help Sri Lankan Tamils to attain their goal of a separate state.

They reasoned that India helped the Bangladeshi people to break away from Pakistan because that weakened their enemy. Since partition, India had to deal with an enemy on its western and eastern borders. After its clash with China it had an enemy on its north. It helped the break up of Bangladesh so that it would not have an enemy in the east.

In Sri Lanka the situation is different. If India helped the break-up of Sri Lanka it may have a friendly neighbour, Tamil Eelam, but would be left with an unfriendly Sri Lanka which could join India’s enemies. India would not help the birth of Tamil Eelam, the militants concluded. That was India’s position then and that is India’s position now.