by T. Sabaratnam, October 29, 2004

Chapter 21

Original index to series

Original Chapter 22

Smashing the Basis

K. W. Devanayagam

Home Minister K. W. Devanayagam’s coordinating secretary K. G. John telephoned me in the morning of 8 September 1983 and said the minister wanted to meet me on an urgent matter. I met him in his ministry.

Devanayagam told me that a Sinhala invasion of his electorate, Kalkuda, had begun and he had conveyed his protest to President Jayewardene. “I want the Daily News to carry the story,” he said.

I was in a fix. I explained my difficulty to him. I reminded him that the Daily News is state controlled and comes directly under the President. The editor would be reluctant to carry that story, as that would embarrass the president, especially in the context of the then Indian mediation. I suggested that he hold a press conference and I would report it.

Devanayagam held the press briefing that evening. He told the media that he had invited them to tell the country of a serious development taking place in Vadamnai that falls within his electorate. He said a large number of landless Sinhala peasants were being brought by a Dimbulagala monk, Ven. Seelalankara Thera, to encroach on the Maduru Oya settlements reserved for Tamils under an agreement he had worked out with Mahaweli Minister Gamini Dissanayake.

Kalkudah polling division

Devanayagam said the Dimbulagala priest had brought about 700 Sinhala peasants on 1 September and had refused to leave when Batticaloa Government Agent M. Anthonimuttu objected. He said the monk had tried to settle Sinhala peasants in the same place in 1974, but had been driven away with the help of the police. This time the police were not cooperating with the government agent.

This time, I found out later, the priest defied the government agent and the police refused to evict him and the peasants he brought because he had the unofficial backing of Mahaweli Development Minister Gamini Dissanayake and his ministry. I learnt that the move to encroach on the state land in Vadamunai was originated by Malinga Herman Gunaratne, a former planter, who was at that time the Additional General Manager of the Mahaweli Authority.

Gunaratne, who had heard a rumour that Tamils of Indian origin were encroaching the state lands in Vadamunai, brought that to the notice of Gamini Dissanayake. The minister told him to settle some Sinhalese there instead. Gunaratne contacted “Dimbulagala Priest” and asked him to settle some Sinhalese in that area and assured him of the Mahaweli Authority’s assistance. The priest acted on that assurance.

Devanayagam circulated copies of the letter Anthonimuttu had sent on 4 September to the Ministry of Home Affairs and copied to him as the Member of Parliament of the area. The first portion of the letter dealt with the history of the settlement scheme. The minister read that portion to the media and said: “This answers effectively the monk’s accusation that Indian Tamils are encroaching the state land in that area. It gives the factual position.”

The letter said that Kallichenai and Oothuchenai were the ancient Tamil villages of the area. An irrigation scheme had been drawn up in 1958 to open up 685 acres of paddy land and highland around these villages for settlement under the village expansion scheme.

Devanayagam said, under an agreement he had reached with the Irrigation Ministry, ten Tamil families of Indian origin were allocated land under this scheme. Later, after the 1977 riots, 48 Indian Tamil families were allocated land under another agreement with Gamini Dissanayake. He added that residents of the two traditional villages were allocated the remaining land. He said 200 Sri Lankan Tamil families from these villages had encroached another 600 acres of the land earmarked for development under the Maduru Oya Right Bank Development Scheme. The minister said that under the scheme of regularization of encroachments of state land implemented by Dissanayake in 1979, these families were entitled for those lands.

Malinga Herman Gunaratne (left)

He said, “These facts show that there is no truth in the accusation that the TULF was instigating the Indian Tamils to encroach on state land in the eastern province.”

Then Devanayagam told the press that a massive attempt was on by Sinhala farmers, led by the Dimbulagala priest, to encroach on the portion of land reserved for the Tamil people under the Maduru Oya Scheme. He added that the land in question was within the traditional areas inhabited by the Tamils. “If the Sinhalese insist on invading this territory, a clash between the Tamils and the Sinhalese is inevitable. I have told that to the President. I told him to prevent another riot. I hope good sense would prevail.”

The Secret Plan

The media was fair. It covered Devanayagam’s press briefing and accorded prominence to the news. The reaction from the Mahaweli Ministry was hostile. A small, but powerful group within the ministry became super-active. It felt that its secret plan to destroy the basis of Tamil Eelam, the separate state for which the Tamil people were agitating , would be thwarted by Devanayagam. It sped up the implementation of their secret plan.

The secret plan was hatched by a Sinhala group in the Mahaweli Ministry. The group was headed by Director of Planning T. H. Karunatilleke and Gamini Dissanayake’s coordinating secretary, Hemapiriya. Some other top officials of the ministry, including some intellectuals with global contacts and reputations, assisted the group. The group brought in a former planter, Malinga Herman Gunaratne, to implement its project. He was appointed Additional General Manager in the ministry.

Gunaratne told me, during a 3-hour meeting I had with him in his Colombo home in 1990, that Gamini Dissanayake was fully supportive of the secret plan. He said he believed that President Jayewardene was also supportive.

Asked for the basis for his belief, he gave two reasons. He said this as his first reason, “The three important men who supported the plan were President Jayewardene’s trusted men.”

The three top men whom he referred were: Ravi, President Jayewardene’s only son, Gamini Dissanayake whom President Jayewardene treated like a son, and N. G. P. Panditharatne whom he made the chairman of the UNP. It is well known these men never kept any secret from Jayawardene.

The second reason Gunaratne gave me was Gamini Dissanayake’s answer to Dasa Mudalali’s query during a fundraising meeting he had in his home on the morning of 6 October, the very day President Jayewardene ordered the arrest of those involved in the Maduru Oya invasion, the details of which I will relate later. Dasa Mudalali asked Gamini Dissanayake whether the President was aware of the plan. Gamini Dissanayake said President Jayewardene was not only aware of the scheme, but was also prepared to give a contribution from the President’s Fund.

The secret plan was hatched in the beginning of 1983, a few months before the July riots, in the air-conditioned rooms of the Mahaweli Authority, which Panditharatne headed. It was hatched in strict secrecy so that the Tamil officers working with the group would be in the dark.

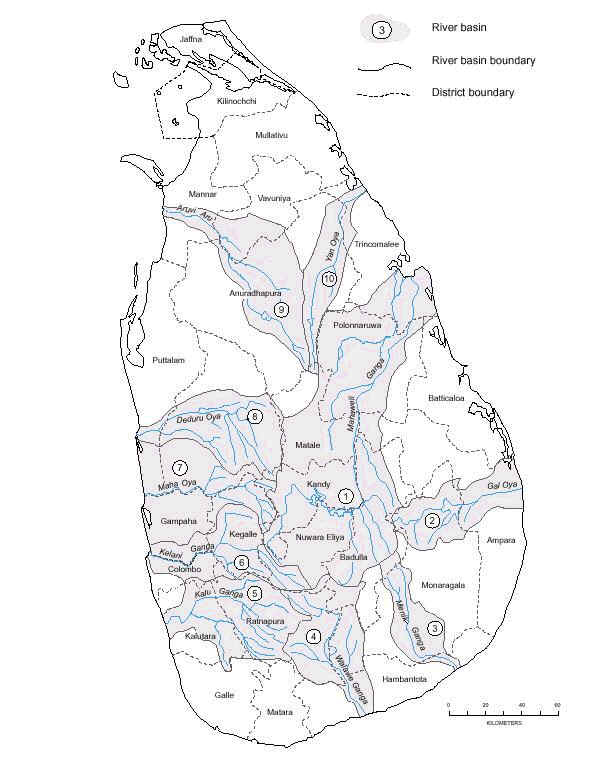

The secret plan was to be implemented in two stages. The first was to destroy the base of Tamil Eelam. This would be done by severing the contiguity and homogeneity of the Tamil homeland through establishing Sinhala settlements in the river basins of Maduru Oya, Yan Oya and Malwattu Oya. The Maduru Oya settlement would break the contiguity between Batticaloa and Trincomalee districts. The Yan Oya settlement would sever the link between Trincomalee and Mullaitivu districts. The Malwattu Oya settlement would fracture the connection between Mannar and Puttalam districts.

The first phase of the plan would leave three isolated Tamil majority areas: the northern province and the districts of Trincomalee and Batticaloa in the eastern province.

Gunaratna has given the details of this plan in his book For a Sovereign State and in the first person account he wrote for The Sunday Times of 26 August 1990. He also told me the contour of the plan during my meeting with him. He said the plan was to settle at least 50,000 Sinhala families in each of these settlements, thus completely altering the ethnic composition of the population in these areas.

I realized during this meeting that Gunaratne is an honest man. I admired his sincerity and dedication to his cause. During the discussion, he asked me, “What are you people fighting for?” “To establish a separate state for the Tamils,” I replied. “If we destroyed the base for Tamil Eelam, you cannot fight for Tamil Eelam, no,” he said. Then he sighed. “They encourage us to do it and then put us in prison to show the world that they are a set of good and just men,” he said and added, “…A pack of jackals.” Gunaratne and 40 others from the Mahaweli Ministry were detained. They were kept in police cells incommunicado. They were also questioned for long periods.

Gunaratne was frank with me because CWC leader and Minister S. Thondaman’s secretary, S. Thirunavukkarasu, had told him that I was Thondaman’s media consultant and I was being sent by Thondaman to meet him about my biography of Thondaman. Gunaratne gave me a full account of his arrest and how Thondaman helped him to be released on bail.

Mahaweli development scheme. Courtesy http://www.fao.org/docrep/X5648E/x5648e0e.gif

“I heard a knock at my door around 4 am and found Assistant Superintendent of Police Ronnie Gunasinghe when I opened it. I saw policemen all round my house. My daughters were the only ones at home. ” Ronnie said that I am under arrest for my role in the Maduru Oya affair,” Gunaratne told me. “I asked him whether the President knew about it and Ronnie said he had ordered the arrest. I asked him whether Minister Gamini Dissanayake knew about it. Ronnie’s reply was: You come to the station we can talk about it.” He said his daughters shrieked when he was pushed into the police jeep.

Gunaratne said his effort to contact Gamini Dissanayake and Panditharatne from the police station failed. Then, he said, he was able to contact Thondaman whom he knew as a planter. “I told him my plight. I told him that I was worried about my daughters. Soon afterwards, I was released on bail. Later I learnt Mr. Thondaman met the President and pleaded with him to let me out on bail. He knew that I was working against the Tamils. Yet he helped me. I am always indebted to him,” Gunaratne said.

The second phase of the plan was to make use of the demographic change brought about by the Sinhala settlements and redraw the provincial map of Sri Lanka. The plan involved the redrawing the boundaries of the following four provinces – Northern Province, North Central Province, North Western Province and Eastern Provinces – so as to create five provinces out of them. The new province that would be created would be named North Eastern Province.

The planned new provinces and the districts that fall under them are:

Northern Province- Districts of Jaffna, Kilinochchi and Mullaitivu.

North Central Province- Districts of Vavuniya, Anuradhapura and Weli Oya (Weli Oya would be made a new district thus reducing the area of the Mullaitivu district.

North Western Province- Districts of Mannar, Puttalam and Kurunegala.

North Eastern Province- Districts of Polonnaruwa and Trincomalee. (This is the new province).

Eastern Province- Districts of Batticaloa and Ampara.

This redrawing of districts would leave only the Northern Province as the Tamil majority province. The rest of the north and east would be converted to Sinhala majority provinces. The southern point of the Tamil majority Northern Province would be Mankulam.

Gunaratne continues to believe in his plan. He has printed the second edition of his book. He believes that the plan failed because it did not have official backing.

Costly Mess-up

The Maduru Oya invasion could not be given official backing. It would offend even the small number of Tamils like Devanayagam who continued to back the Jayewardene government after the riots. It would have strengthened the position of the Tamils who had earned the sympathy of the international community. It would have angered India.

Jayewardene and his men wanted to do it in the sly, but the Mahaweli Ministry mounted a clumsy, massive operation and spoilt the whole thing. It also landed Jayewardene and his government into a pickle.

Devanayagam’s 8 September press conference had the opposite effect than he intended. The Mahaweli Ministry speeded up the operation. Officials asked the priest to quicken the pace of the settlement. He did everything openly. He placed an advertisement in the Sinhala daily Dawasa calling for cultivators to be settled in the paddy land in the Mahaweli irrigation scheme. He also sent a circular to the Nayakas (chief priests) of Buddhist temples to send at least two landless peasant families. He led a peasant army of about 700 persons, alerting the government agent and other officials. When the ‘army’ refused to go back and the police refused to cooperate, Anthonymuttu informed the Home Affairs Ministry and Devanayagam, the MP of the area.

The Mahaweli Authority also did everything openly. Its fleet of lorries transported the peasants from the Dimbulagala temple to the settlement site. It ferried poles, tin sheets, cadjan and other materials needed to put up sheds to house the settlers. It carried stocks of cement and provisions needed for the settlers. The Mahaweli Authority’s tractors and bulldozers cleared the land needed to put up the sheds.

Anthonimuttu reported to Devanayagam on 15 September that the number of peasants had swelled to about 40,000. Devanayagam held his second press conference the next day and announced that the situation was worsening. He said the Tamils of the Batticaloa district were getting agitated and a confrontational situation was developing.

Devanayagam charged the Mahaweli Ministry with complicity. He produced photographs to prove his allegation. The photographs showed lorries and other vehicles belonging to the Mahaweli Ministry transporting men and material. They showed Mahaweli Authority officials, contractors and workers in action.

Photographic evidence was fortified by eyewitness accounts of journalists. They described the situation in the Maduru Oya area as that of a carnival. “People are pouring into the Dimbulagala temple from all parts of the country. They are being transported in lorries and vans to the location. Mahaweli Authority officials were directing them to various places and providing them with poles, tin sheets and cadjan to put up temporary sheds. Food parcels were also being distributed by volunteer organizations,” the Lake House Polonnaruwa correspondent reported.

Dimbulagala temple

Rumours were also floating in Colombo grapevine about the behind-the-scene maneuvers of top-level Mahaweli officials. It was rumoured that Gunaratne had told Gamini Dissanayake about the desirability of obtaining army protection for the operation, which the minister had turned down, saying that the army had other work to do. He told Gunaratne to make alternate arrangements. It was said Panditharatne had telephoned the Defence Ministry and arranged for the services of naval officers dismissed for burning Tamil shops and houses in Trincomalee before and during the July riots.

A highly worked-up Devanayagam issued two warnings during the press briefing.

He said, “If a Sinhala- Tamil clash is to be avoided, the squatters should be sent away.” If appropriate action was not taken, he said, he had no option but to resign from the cabinet.

President Jayewardene was upset when these threats appeared in the media. He knew that he could not afford to have another riot and he could not afford to lose Devanayagam. Devanayagam was his showpiece to the world. He and Thondaman were shown as proof of Jayawardene’s benevolence to the Tamil people. Another riot or Devanayagam’s resignation would damage him and his government more then the gain the Maduru Oya settlement would bestow on him.

Jayewardene summoned Devanayagam and pacified him. “I will deal with the matter. Please bear with me,” he pleaded.

The Abandoned Fund

Gamini Dissanayake was not concerned about these consequences. He had his political goal. Playing the role of a modern Duttugemunu was the sure path he had to ensure his political future. He summoned a meeting of top Sinhala businessmen at his home and spoke to them about the plan to destroy the base of Tamil Eelam. He got his Mahaweli officials to explain the secret plan. He said the state would not be able to undertake the plan as it would upset India. He suggested that a private fund be established to finance the project.

Gamini Dissanayake

Dasa Mudalai asked whether the President was aware of the plan. Gamini said that he was in the know. He added that the President had indicated his readiness to donate money from the President’s Fund. He told Dasa Mudalai to pick a name for the fund and to select an auspicious day for its inauguration.

The inauguration meeting was also held at Gamini’s house and Dasa Mudalali gave the first cheque for one million rupees. Others present also made their donations. They pledged a total sum of Rs. 3.5 million rupees. The cheques were not cashed because the next day Jayewardene ordered the arrest of Gunaratne and other prime movers of the plan and the eviction of the encroachers.

Gamini Dissanayake panicked and disowned having anything to do with the Maduru Oya settlement.

Jayewardene was under tremendous pressure from India and the international community. TULF leaders who were in Chennai at that time alerted Indira Gandhi. Amirthalingam, who was in London, telephoned Parthasarathi and Indira Gandhi and said the Maduru Oya invasion showed that Jayewardene was keen to complete his final solution to the ethnic problem. Amirthalingam later told me that Indira Gandhi was annoyed. New Delhi told Chhatwal to meet Jayewardene and convey India’s displeasure.

Chhatwal did that. He told Jayewardene that India was worried and displeased with the Maduru Oya invasion. Jayewardene was angry. His wrath turned towards Gamini Dissanayake. He felt that Gamini Dissanayake had let him down. He felt that he had messed up the whole affair. Instead of settling 500 or 1000 families, he had sent 45,000!

Jayewardene held a series of high-level conferences with Mahaweli Authority officials. He asked Panditharatne to evict the encroachers. Panditharatne said that “Dimbulagala priest” had taken the peasants there. Jayewardene was irritated and said, “If Dimbulagala priest is going to run the Mahaweli Authority, I will appoint him the chairman and you can go home.”

Panditharatne and other officials played down the invasion. They told President Jayewardene that the reports appearing in local, Indian and international media were exaggerated. They told him only about 2,000 peasants had gone to the Maduru Oya basin. But Lalith Athulathmudali and others told him most of the media reports were correct and implanted in Jayewardene’s mind the thought that the matter had been mishandled. Athulathmudali saw in Jayewardene’s discomfiture an opportunity to edge closer to him.

Jayewardene’s style of governance had created pitfalls for him. He promoted rivalry among his own men. Lalith and Gamini were young and ambitious men. They openly promoted themselves as Jayewardene’s successors. Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa was also aiming for the same position. It was well known that Gamini was Jayewardene’s blue-eyed boy. He was given the most important ministries of land and Mahaweli Development. Lalith, from the start, was trying to get closer to Jayewardene.

Prof. A. J. Wilson, who was very close to Jayewardene during this period, has commented about this rivalry in his review of J. N. Dixit’s book Assignment Colombo printed in Sunday Island of 8 February 1998. Wilson speaks about the intrigues that went on in Jayewardene’s court among Premadasa, Gamini and Lalith.

“It was pretty certain that JRJ (President Jayewardene) had decided to bequeath the Presidency to Gamini who as Thondaman once said was ‘President’s pet’. In my conversations with JRJ I concluded that he had a warm heart for Gamini and in fact after the victory at the 1982 presidential elections it was quite clear to me that he was planning to make Gamini the prime minister getting rid of the incubus that was Premadasa,” Wilson wrote.

Lalith knew very well that he would not be the anointed successor. He used to tell those close to him that he was considered latecomer to the UNP but that he would reach the top the same way he climbed to the top at Oxford, first as the secretary of the Union and then its president.

Lalith’s Opening

Lalith saw in Maduru Oya mess-up his opportunity. He told the President that the Maduru Oya invasion had eroded his international image. Jayewardene was subjected to immense Indian and international pressure. His anger turned towards Gamini and Panditharatne. He refused to talk to them. He declined to listen or believe them.

Paul Perera

Jayewardene asked his confidant, Paul Perera, to fly over the Maduru Oya Basin and report to him. Perera flew over on 1 October. I telephoned Paul Perera soon after he returned to Colombo. He told me he saw a mass of huts when he looked down from the helicopter and estimated the number could be “well over 20,000.”

Jayewardene appointed Paul Perera the Additional District Minister of Polonnaruwa and authorized him to evict the settlers using force if necessary. Col. Benedict Silva of the Volunteer Force was appointed his assistant. Paul Perera did not rush to do his job. He prepared the ground through the media. He gave me a special story. In it, he appealed to the settlers to get back to their villages. He said private individuals have no authority to allocate state land to the peasants. And he subtly indicated that, if the settlers fail to respond to his appeal, he would be compelled to use force to evict them.

Paul Perera did his job meticulously. He used the police and the army to evict the squatters. He went to Polonnaruwa and met police and army officers. He told them to act with tact. “They were all misguided people. Don’t harm them,” was his strict order. The squatters were all chased out. “Dimbulagala priest” was also sent away. The priest resisted. The police told him that they were carrying out President Jayewardene’s order.

Lalith had climbed the ladder. He was appointed the Minister of National Security and Deputy Minister of Defence eight months later, in May 1984 and emerged as the most powerful Minister. That also made him the main rival of Premadasa. Gamini Dissanayake was eclipsed. It took Gamini three years to win back his prominence. He had to work his way up by earning India’s friendship and emerging as the main man behind the negotiation of the Indo – Sri Lanka Peace Accord of 1987.

“Dimbulagala priest” rushed to Colombo to meet Gamini Dissanayake and Panditharatne to get their assistance to press President Jayewardene to reverse his order. He went to the Mahaweli Ministry, but Panditharatne and Gamini Dissanayake declined to meet him. He visited all newspaper offices in Colombo. He visited Lake House and met the Dinamina editor. Then he came out of the editor’s room and met the editorial staff. The Daily News News Desk is adjacent to the Dinamina News Desk. I was present at the Daily News News Desk at that time.

The monk was fuming. He was shouting at the top of his voice. He charged that Paul Perera was indulging in anti-national and anti-Sinhala actions. He charged that Paul Perera was doing this because he was a Christian. He raised his umbrella and said: If I see him I will hit with this.”

Jayewardene had to distance himself from the Maduru Oya operation. He could not risk the resignation of Devanayagam. He could not risk another riot. More than those, he could not risk an Indian military operation. He was informed by High Commissioner Bernard Tilakaratna that Indira Gandhi was angry.

Jayawardene went through the motions of sorting it out. Gunaratne and forty other officials were sacrificed. He did not abandon the concept of smashing the base of Tamil Eelam. He sidelined Gamini Dissanayake for messing up the operation. He handed over the job to Lalith, Gamini’s contender. Lalith was given the job of managing the Yan Oya Basin settlement. That will be the story I will relate in the next chapter.

Next: Chapter 23: Manal Aru becomes Weli Oya

To be posted November 5