by Watchdog, Colombo, July 12, 2023

For years, Sri Lankans have risked everything, trying to escape their homeland. Crushed by a failing economy, cold-hearted politics, and the brutal realities of world events, many venture into the unforgiving sea. Few return. This is their story.

Story by Andrew Fidel Fernando and Mohammed Fairooz

Additional reporting and translation by M.F.M Fazeer and Yathursha Ulakentharan

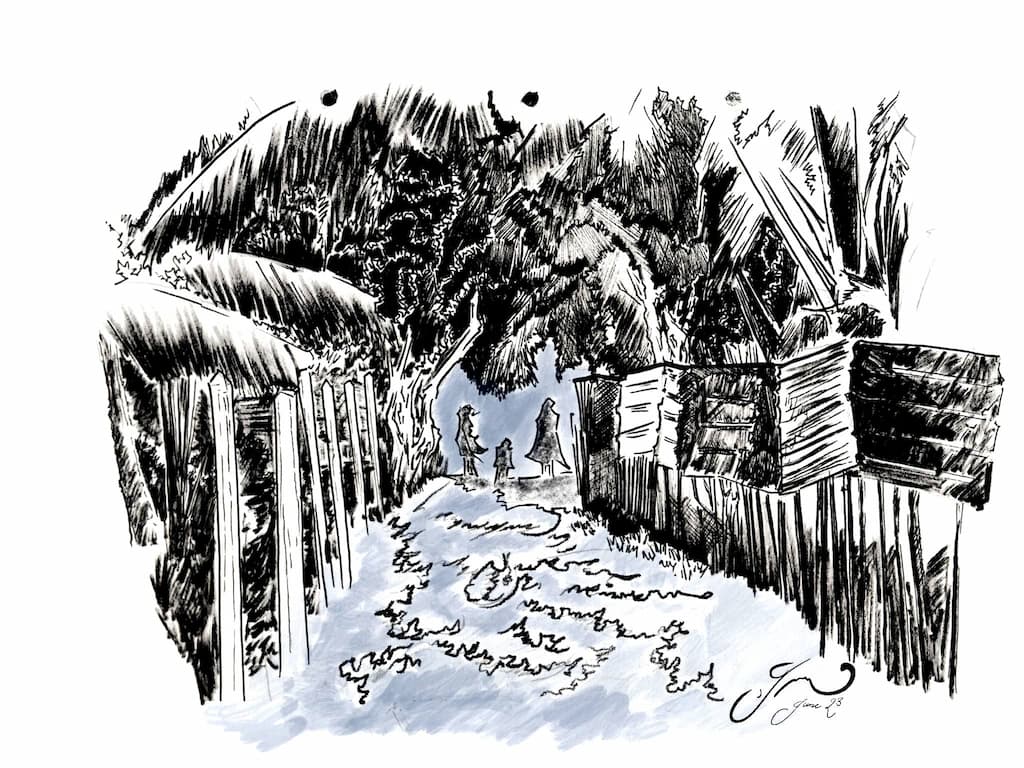

Art by Joshua Perera

Edited by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne

K. Venuja thought her husband’s plan to migrate was fraught with danger. But he was adamant. “This is not like the boat journeys everybody takes,” S. Kiritharan had told his wife. “Not like the ones where they get caught and sent back. This is sophisticated. And it’s a good route. It’s all organised.”

The ‘agents’ had worked on Kiritharan, 37, for months. A regular customer at his trishaw repair garage in Chavakachcheri, just east of the city of Jaffna, had introduced him to them. “Don’t worry,” the ‘agents’ had said. “This is a sure thing.” As he was a mechanic with more than a decade’s experience, they would give him a huge discount in exchange for his help with maintaining the boat’s engine.

Better yet, he’ll find a job, no problem, when he gets to Canada. Shu! Don’t worry at all. Within a few months he’d have made the money to cover the journey. Not long after that, they’d be clear of debt. Maybe the family could even join him in 12 months.

Venuja, 33, remained unconvinced. The pair would argue in their modest two-room home, its walls mostly made of bamboo. Venuja held staunchly that if Kiritharan was set on going abroad, going to the Middle East legally was the safe choice.

Kiritharan disagreed. What did she know about the outside world when she spent most of her days in the house?

He had the ‘agents’ speak to Venuja directly.

“Normally the cost is one crore,” a voice on the phone had told her. “But because of your husband’s skills, we are only charging 15 lakhs.”

“What if he gets caught and gets put into a detention camp?” she had asked.

“That won’t happen. But even if it does, we will pay you while he is there.”

Even Venuja had to admit, however, that the family’s financial situation was desperate. It had been Kiritharan’s migration to Saudi Arabia in 2014 that had tipped the family down the steepening slope into debt – Kiritharan never making enough in his short stint there to pay their creditors off.

Eight years later, they were plunging hopelessly into a ravine, rushing to one microfinance company for the cash to pay another. They had three children and costs to cover.

They were also expecting a new family member. Venuja’s due date was fast approaching. As the economy crashed, and cost of living shot way up, Qatar seemed insufficient. Problems of this magnitude needed a more serious solution. A solution such as Canada.

When the long, fat fuel queues of June 2022, which brought traffic around the island to a halt and ruined what was left of Kiritharan’s business, he made his decision. He sold his machinery, plus other equipment he had bought with a view to eventually opening a service station.

Pawning jewellery, some of which belonged to family and friends, he raised the money to get his documentation in order – a passport, flights to Myanmar, along with a tourist visa. It was from Myanmar that they’d board the ship he said to his wife. “See? Sophisticated.”

Sitting in a plastic chair on the sandy, sunbeaten yard outside their home, Venuja is matter-of-fact as she tells us about how systematically the ‘agents’ had extracted their money. They’d asked for eight lakhs at first. Then for three more. Then another two. The family had already committed so much, they had little choice but to follow through. It never seemed likely that they’d get a refund.

“When they asked for more and more money, I told Kiritharan we’d have to borrow more at high interest. The agents said, ‘Yes yes everything has come together for him now, please go ahead and borrow the money.’ They spoke in a very believable way.”

She also remembers Kiritharan having been joyful in the days before his departure. “He was convinced this would work.” Her two boys, aged 10 and 5, flit in and out of the scene as she speaks to us. Her 13-year-old daughter sat beside her. The baby is sleeping in her daughter’s arms.

Their youngest hadn’t been two months old when Kiritharan left home, boarded his flight on August 26, and later arrived in Yangon.

The family would never see him again in the flesh.

Sanju* would soon board the MV Lady 3 fishing trawler at Yangon, same as Kiritharan, but before that, he took a flight from Colombo to Bangkok, then Bangkok to Yangon. It is possible they were on the same flights. Though the two did not meet each other until much later, Kiritharan had also left on August 26.

On the way to the hotel south of Yangon, which the smugglers had organised, Sanju ran into 11 others from across the north and east. They had all been told the same thing: get to this guest house, and await further word.

It took seven weeks before the ship was ready – weeks filled with anxious calls to the agents, frantic sharing of information among those collecting in the Yangon hotel, a view coalescing that they’d all been duped and would be stranded here forever.

Men who worked for the “agents” turned up every now and then with instructions to wait a little longer. They also made fresh demands for money. A seaworthy ship was going to cost more than anticipated, they’d say. Or that the tightening of one of the borders on the route meant the smugglers were now required to slip a bigger bribe to maritime officials.

Sanju and the others were in no position to refuse.

Eventually, in early October, word arrived that the ship was finally ready. Sanju boarded a bus that took them south, towards the mouth of the Yangon river. At a small port there, they clambered onto a dinghy that ferried them out to the bigger vessel.

Even when they’d boarded, in the dead of night, the “ship” – the Lady 3 – had seemed small for one about to attempt an 18,000-kilometre crossing. When light fell on the vessel, it was clear this was no ship. It was roughly 40 meters, end to end – at best a large fishing boat, rusted in parts, and decaying.

Worse, it was bursting with passengers, putting the boat at serious risk of capsizing when the deck was crowded. There was barely space to stand, let alone sleep. Before they’d even set out, the passengers began to grow furious. How were they possibly going to last three weeks on this boat? Of the passengers, 10 were children; 24 were women. All but a handful were Tamil.

The crew, likely made up of Myanmari sailors, stayed in the bridge, which was on a higher level than the deck on which the passengers were allowed. They kept their faces covered with bandanas.

Early on, they assured the passengers that they’d be transferred to a larger vessel once they’d reached international waters. Through the course of the journey, they’d keep promising that the new ship was a short sail away.

Once the vessel set out, travelling south through the Andaman Sea, the hardships began to compound. The passengers could only nap in shifts, the sleeping area unable to accommodate more than about fifty people at a time. Exhausted even by the time the boat rounded the Malaysian peninsula, the passengers were forced to spend daylight hours crammed below deck as they moved through the narrow Strait of Singapore, where other naval traffic might report a visibly overfull boat to authorities.

The stench was growing unbearable. There were only two toilets aboard, and many of the passengers were vomiting from seasickness, having never been aboard an ocean-going vessel before. Even those that could keep food and fluids down had little to eat. The passengers had not been allowed to bring aboard their own meals, and the trawler was desperately short of supplies.

The drinking water, stored in a heavily rusted tank, was bright orange. It would lose only a little of its colour after triple-straining through cotton shirts. On just the tenth day, with more than two thirds of the journey to go, severe rations were imposed – the boat having run out of everything but rice. For the remainder of their voyage, they drank a thin gruel of rice and rusty water, with the occasional addition of seawater, to conceal the nauseating metallic taste. When eventually it rained, they fashioned funnels out of tarpaulin to collect potable water.

The high winds and storm surges that accompanied the downpours, however, presented their own challenges. The leaks had sprung early on; the sloshing of seawater heard from deep within the hull as early as the eighth day of the voyage. When the crew were alerted, they asked passengers to form a human chain from the bowels of the boat, where the leak was, up into the deck. They had almost no equipment with which to bail the vessel out. Mostly, the passengers soaked the seawater up with their own shirts, skirts, and sarongs, before passing the dripping clothing down the line to be wrung out over the gunwale.

The leaks were plugged temporarily with bits broken off rubber flip flops, and further clothing. This slowed the flow of water, but whenever the boat struck a large wave, or the trawler hit bad weather, the hole would grow, and more debris had to be found to fill it. By the 25th day, the boat was taking on substantial quantities of water, and the passengers had to be organised into shift-crews, the bailing now having become a 24-hour operation.

As illness, fatigue, and hunger began to take hold, tensions rose ever higher. The crew holed themselves up in the bridge, emerging only to bark instructions. When passengers demanded to be taken to the nearest port, believing their lives to be in serious peril, crew members snapped at them. “Another ship is being prepared for you to board in the South China Sea,” they’d said.

On the 27th night of the voyage, while the trawler was sitting low in the water, with 303 passengers on board, and virtually no food, the crew called out for a small boat from shore and escaped into the darkness. When passengers yelled to them, they hollered back that they were going to fetch supplies to fix the leak.

On board were two Tamil fishermen, with a lifetime’s experience on the ocean. They knew the truth: the trawler was going to sink.

Sixteen kilometres north of Trincomalee, a broad, ornate building rises out of tawny-coloured soil on the side of the Pulmoddai road. Three businesses pack out the ground floor: a pharmacy, a photo studio, and a bakery. Next level up, a recently-finished apartment is fronted by tall windows and a mahogany door, the walls painted strikingly in burgundy and white.

Inside, the first sitting area leads to an open-plan living and dining space, with a modern kitchen gleaming with new appliances. But for the colour palette – which favours the powder blues and pastel shades beloved of Sri Lanka’s northeast – this could easily be the interior of an apartment in Sydney.

The building towers above the sleepy village of Irakkakandi. There is no greater monument to prosperity for many kilometres.

It had been in 2012, that the building’s owner, Mohammad Ramzy had migrated, undocumented, to Australia. His was an unusual venture; he and his friends had essentially smuggled themselves.

Having sold belongings and property, Ramzy and four others pooled their capital to buy a second-hand fishing vessel. There were further expenses; they had to hire a skipper, buy accurate maps and GPS equipment, as well as supplies for the trip. Late in the year, they departed from Pudawaikattu, about 38 kilometres north of Irakkakandi.

MSM Saheed, a fisherman who signed on to the venture late, remembers the voyage to Cocos Island being traumatic. They had enough food aboard and the boat had been well-chosen. But Ramzy and one other passenger were desperately seasick.

“They each would have kept down a single packet of biscuits across the whole 20-odd days it took us to get to Cocos. It was that bad,” Saheed says. “The rest of us were like their full-time nurses.”

Once, when a boat hit a squall near Indonesia, the captain argued the sick men be cast overboard. “They’re not going to make it anyway,” he’d said. The mere suggestion had horrified Saheed. He remembers immediately wanting to return home – his humanity too great a price to pay for the chance to build a better life.

Not long after the passengers were taken to one of the Australian government’s centres after being intercepted in the waters near Cocos, Saheed asked to be sent home.

Ramzy remained. After several months, he was allowed to leave the processing institutions and begin work in Australia. More than 10 years later, he runs a cleaning business in Sydney. He has not returned to Sri Lanka while his asylum and residence applications work their way through the system. But although he has not been around for his children (now aged 19,15, and 12), the money he has sent back has visibly transformed the financial status of his family.

There are many more stories of rapid financial advancement. In Udappu, a coastal town just north of Chilaw, S. Naresh told us how he could not have possibly built his two-story home if not for the eight years he’d spent in Australia, having got there by boat in 2012. Naresh had had time left on his visa, but chose to return early to marry. “Hard to think I’d have been able to have all this if I didn’t go to Australia, no?” he says. He also owns a grocery close by.

Further south, in neighbourhoods on the stretch from Chilaw to Negombo, terra-cotta driveways lead to plush, Italian-style villas built with money sent from Europe in previous decades.

In Jaffna, a young woman told us about her uncle, who, near Mullaitivu some time in 2012, had walked to the beach to relieve himself. He spotted a boat full of locals setting out to Australia. Afraid this uncle would raise the alarm with authorities, the smugglers on board had kidnapped him in just his sarong, and bundled him off to Australia with the rest of their passengers.

“He’s still there,” the woman told us. “He’s educated his children and some of them are overseas now too.”

To what extent stories such as this are true is moot – they do a roaring trade. Glossed over in the retellings are the potential traumas such an abduction may inflict – the difficulty of the journey, the loss of contact with family, the act of being transplanted against his will to a place in which he does not speak the language.

In the popular imagination, he has won the lottery. Following his release in Australia, his financial success is believed to be both inevitable and frictionless.

Many on the Lady 3 were convinced their lives were about to end. When the crew fled they had shut the engines off, and the vessel was now helplessly adrift in the South China Sea. Shoved to breaking point by sheer exhaustion, some passengers spiraled into a state of despondency.

“Everyone was scared,” Mathushan, a 21-year-old from Jaffna aboard the Lady 3 told Canada’s CBC. “Many people cried, many people screamed and shouted.”

Others began to act in desperation. Sanju remembers clothes being lit on fire with the hope of attracting the attention of distant ships. One group went into the belly of the vessel to bail, reasoning that this act at least would buy time, though by this stage the boat was filling fast.

It was afternoon by the time the passengers made a literal breakthrough. Some had gone up to the bridge and busted down the door, which had been locked by the fleeing crew. There, they discovered a satellite phone, and dialled home. It was likely one of the fishermen aboard who had the number for Sri Lanka’s MRCC memorised.

“They were very lucky actually,” Rear Admiral Rathnayake says. “They called the MRCC, and we’re the ones who alerted the Singaporeans immediately. That was the closest rescue centre to the vessel. At that time, the passengers told us that the skipper went ashore to fix something and never came back. They were in grave danger. So we activated the rescue system. We also called our ambassador in Singapore.”

Rathnayake can’t help but indulge in self-congratulation. “After everything, we were the ones they called from their satellite phone. Monava hari unahama thamai mathak venne. It’s only when something bad happens they remember us. They know we take action.”

In any case, it was a 200-metre Japanese-flagged vessel called the Helios Leader that responded to the Singapore MRCC’s distress call. Captain Anil Chaudhary, who helmed the 60-thousand ton vehicle-carrier, described his response to Watchdog in the language befitting a captain’s report:

“Helios Leader was sailing on a passage from the port of Nagoya in Japan to the port of Singapore,” he told Watchdog. “On November 7 2022, at 1450 local time, when MRCC Singapore broadcast a distress message on Inmarsat system and requested lookout and assistance for a boat Lady R3 with 300+ persons on board. I calculated the distress position to be about six nautical miles on our beam and so I Immediately altered my course and proceeded towards the marked location to investigate.

At the same time I informed my intention to MRCC Singapore.”

But when Helios Leader arrived at the marked location, Lady 3 could not be seen. Captain Chaudhary continues:

“Weather had worsened and there was a swell of three-to-four metres with northeasterly winds, Beaufort Force four-to-five. We reported the situation to MRCC Singapore and in consultation we expanded the search area.

“After about 30 minutes, we detected a target in the direction of the drift another seven nautical miles (13 km) off. I decided to investigate and reached the target by 1630 hrs when the boat Lady 3 was identified. This boat was observed to be disabled with no engine power or steering, It was noted to be moving violently in the waves, the boat was also taking water. It was only a matter of time before she would be flooded.

“The boat was overflowing with people. There were hundreds of men, women and small children who were screaming and shouting for help, most of them were on the deck and wearing lifejackets. They knew this was a bad situation.”

The details of the rescue are nothing short of heroic. As the ship’s chief engineer Dinesh Khanna spoke Tamil, the Helios Leader’s crew quickly understood the urgency with which they had to act.

They wrapped mooring ropes around bollards on their own ship, flung them over to be secured to Lady 3, then tossed a pilot ladder down for passengers to climb up on to the substantially larger vehicle carrier.

But this wasn’t going to work. “To climb up the ladder you had to be alongside the ship,” said Khanna to the Straits Times. “With the waves, both the vessels were moving up and down. It went haywire.”

There was panicked screaming from those on Lady 3, but now also a mad rush towards the ladder, in order to be among the first extracted. Through the hailer aboard, the Helios Leader’s crew tried to calm Lady 3’s passengers. “We had to tell them not to climb on altogether because if somebody fell, we would have to save that person first.” Khanna had said. The crew reassured them too: “We won’t leave this place until we see the last person leave safely.”

Here’s Chaudhary again:

“Our ship is a commercial vessel with limited staff of just 26 and we don’t have the resources or training to engage in such a huge rescue operation, especially at high seas in the given worsening weather, In a normal rescue operation we tend to launch our rescue boat which can go to the survivors and pick them up and bring back to our ship. Such a operation would require 30 to 60 mins for one trip and we can rescue only 10-20 persons at a time by this method.

“Seeing the gravity of situation and darkness approaching. I opted for an unconventional rescue operation by manoeuvring our huge car carrier alongside the small disabled craft.”

Over the next few hours, having secured themselves to their own ship with harnesses, the crew reached down to lift each of the 303 passengers off the trawler, and into safety, on the Helios Leader. Chaudhary was on the bridge for much of the four-hour rescue, skilfully manoeuvring his own vessel.

“It was challenging to keep both the vessels alongside each other. They were moving vertically up and down at their own time and we were also being swept away by the winds and seas. We had to continuously uses the ship’s engines and thrusters with helm to maintain our position and also keep the small boat in our shelter.”

Not much more than five hours after receiving the distress call, the Helios Leader’s crew had left no one behind, raising the last man off Lady 3 at around 8pm. They had even saved much of the passengers’ luggage, which had been flung across from the smaller boat.

“If they had come even 90 minutes later, they would not have saved us,” says Sanju. “So much water had risen inside the boat.” Some of those who had been on Lady 3, bent down to touch the feet of the Helios Leader’s crew, grateful to be alive.

The passage to Vung Tau took all night, with the passengers all housed in Helios Leader’s cargo hold – the only space that could accommodate them. Chaudhary had his cooks prepare bread and soup, while medical assistance was provided to those who required it.

“When we reached Vietnam, we were informed the boat had foundered and sunk in the same location immediately after the rescue,” Chaudhary says.

At Vung Tau port, an official from Sri Lanka’s diplomatic mission to Vietnam had arrived to receive the migrants. Initially there was some reluctance to disembark. “We told them this is not where we wanted to go,” Sanju says. “The woman from the embassy was telling us that we would be sent back safely to Sri Lanka, but we said that it’s wrong to repatriate us, because Sri Lanka is not safe. We raised demands that the UN should get involved and provide a solution.”

“We did our best to explain to them that our ship is not designed to accommodate such a huge number of survivors for more than a day or two, and also that the Vietnamese government had volunteered to accept them all without conditions and had arranged good receiving facility ashore for them which they should avail,” Chaudhary says.

“After a few hours, they understood that we had already shared all our provisions food and water with them and soon we too would be helpless. The best opportunity for them was to avail the resources ashore, which I am glad they accepted. By 1700 local time they started to disembark and be documented ashore. Both trips to transport them were completed by midnight.”

Back in Chavakachcheri, Venuja had watched the news for many weeks, hoping to discover something about her husband’s progress, but also knowing that as he was attempting an illegal passage, Kiritharan might be best off if the news had nothing to report.

When she learned that passengers on a boat headed to Canada had been rescued off the coast of Vietnam, she had not believed that her husband could have been aboard. The agents had promised he’d travel on a proper ship.

But then Kiritharan called her from Vung Tau, Vietnam.

Among the first things you learn about the process of migration is that it is governed by ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors. Push factors displace residents. They can be war, pogroms, ethnic repression, or economic hardship, none of which Sri Lanka has been short of in the past 50 years. Pull factors draw the displaced in – migration to these locations driven by the likes of perceived political or religious freedom, a vibrant economy, and strong, just institutions.

But much of what is known about migration is from its legal, documented pathways. Sri Lanka, however, has a vast modern history of undocumented migration.

Folks from the North and East fled to India and elsewhere in droves in the nineties and aughts, away from the war and the repression of both the Sri Lankan state and the LTTE. So many found homes elsewhere that the economies of the northern and eastern provinces function on the back of those who made it to developed nations.

There were other routes out in decades past. Many youth from the Catholic belt between Negombo and Kalpitiya were smuggled across the Arabian Sea, through the Suez Canal, and up into Italy, to work in restaurants, gelato joints, bakeries, delis, factories, and garages.

In 2002, Sri Lankan police estimated that 2000 Sri Lankans were smuggled on vessels headed to Italy. This is until the Sri Lanka and Italian authorities worked together to shut this route down, through the mid aughts.

But while Italy’s pull diminished, the draw of other nations surged, Australia chief among them. Many Sri Lankans were embedded there already, which to undocumented migrants meant temporary accommodation, and leads on jobs. It is also a nation in which the minimum wage has been exceptionally high – a significant pull factor for undocumented migrants, who tend to occupy the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder (currently, Australian minimum wage is at AUD $21 per hour – roughly LKR 4300).

And you may not have to travel as far as you think. Cocos Island, an Australian territory, sits south of the Indonesian island of Sumatra. If you make a beeline from Trincomalee, it is roughly a 3850 kilometre journey. In 2012, 6412 Sri Lankans made the voyage to Australia. Sri Lankan authorities said they had intercepted a further 3000 headed there in the same year.

Today, the forces pushing people out of the island have again become acute. Following 2022’s economic crash, seven million Sri Lankans now live in poverty; at least 50% have exhausted their savings to meet day to day needs; 32% have sold their household assets to survive; and almost half have reduced the amount that they eat.

Where the navy had nabbed a total of 668 people attempting to migrate by boat in the seven years between 2014 and 2021, they apprehended 1542 in 2022 alone.

If you set out from Talaimannar, the village at the northwestern tip of Mannar island, “you might reach Indian waters inside 25 minutes” the navy’s deputy chief of staff Rear Admiral Pradeep Rathnayake told Watchdog. Most who get to India seek a journey onward.

Many others, such as Kiritharan, have left Sri Lanka legally, by air, before boarding the vessels that are to transport them illegally to developed nations.

Yet more may not board a boat at all. In Trincomalee, we heard of one route, where you fly to Eastern Europe on a tourist visa, and are then required to work undocumented for an “agent” there for a year, before they pack you into a crate, and slip you into the European Union in the back of a lorry.

Then there are those about whom we know very little. In January 2019, a 90-foot fishing trawler left Kerala carrying 248 passengers, many of whom are believed to have been Sri Lankan. Supposedly this vessel was headed for either New Zealand or Australia.

But there is no official record of it arriving anywhere.

Despite this, desperation continues, accelerates. Unsurprisingly, people smugglers have sprung out of shadows all through these parts, whispering dreams, spinning vast webs of deceit. The economic crisis is the cruelest of jokes – brought about by a president northerners in particular had voted desperately against. And though the crash has caused ruin all over, its maws closed especially menacingly here. By mean household income, the north and east had been the poorest provinces before the global pandemic hit.

The situation has only worsened since.

The Australian government has been chief among the foreign nations warning Sri Lankans about the treachery of smugglers. In the media, and in the Australian vernacular, those making these voyages had already become known as “boat people”.

In 2013, Australia voted in the ultra-conservative Tony Abbott, won over at least partially by his “stop the boats” message. Abbott put in motion an ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’, and over the last ten years, they’ve unrolled sprawling ad campaigns, across almost every medium. If you’re in Sri Lanka, chances are you’ve seen at least one “Zero Chance” message. “No way!” The words glower down from Tamil-language billboards across these provinces. “You will not make Australia home!”

In its campaigns, Australia has harnessed the hardships endured by Sri Lankan working and middle classes to serve their hardline immigration message. Between 2019 and 2022, the Australian government even put on an annual “Zero Chance” film competition, in which budding Sri Lankan film-makers were to submit a short piece.

The top prize for the most-recent of these competitions – run in 2021 – was a mid-range DSLR, worth roughly USD $1500. “Why should we do their advertising for them, if a camera is all they are offering,” said one filmmaker from Jaffna, who’d entered the competition one year, and hadn’t won. “We’re only telling people what they already know.”

Some of these campaigns, indeed, are trying so hard that they border on the farcical. Another short film, this one funded more directly by the Australian government, appears – professionally shot and acted, albeit with the oversweet tenor more at home in a shampoo commercial. In it, a Sri Lankan woman tells her friend about the time her husband had been desperate to travel undocumented to Australia, but she had convinced his family not to fund his ill-fated trip. “Behind every successful man is a woman,” the character tells her friend. “The woman must be even smarter than the man… We can see the future more clearly than a man.”

In the same vein are the fake horoscopes manufactured by the Australian government. “You will lose your wife’s jewellery,” says the Gemini horoscope. “If you illegally travel to Australia by boat you will be returned. Everything you risked to get there will be in vain and you will end up owing everyone,” proclaims the Sagittarius.

The Australian Government has substantially increased its support to Sri Lanka since the onset of the economic crisis, committing a total of approximately AUD $75 million (approx USD $49 million) in 2022, Australian High Commissioner to Sri Lanka Paul Stephens tells Watchdog. That’s essentially four times what they generally provide. Australia’s “big interest [in deterring illegal immigration] is to ensure the safety of lives at sea,” says Stepehens.

As with things of this nature, the ‘boat people’ aren’t just exploited by smugglers. In May 2022, staff of right-wing Prime Minister Scott Morrison urged border officials to publicise the interception of a boat carrying Sri Lankans. This was an attempt to reiterate the Morrison government’s credentials at being tough on undocumented migrants, as Australians went to the polls that day.

Asked how much Australia’s government spent on Zero Chance, Stephens says he does not know. “We have a command in Australia – Operation Sovereign Borders. It’s headed by a Navy official within the department of Home Affairs. It’s not Sri Lanka-focused at all.”

This latter statement is especially ironic, given the horoscopes and the billboards and the 233 videos available on the ZeroChanceLK channel – videos in Sinhala and in Tamil. Stephens says he’s happy with the Zero Chance campaign and how effective it’s been, but is unaware as to how the High Commission in Sri Lanka might measure that impact.

Asked whether it was possible that Australia’s messaging in Sri Lanka had merely made Australia less attractive to undocumented migrants, and diverted them to other parts of the world, Stephens says this: “We don’t know.”

We spoke to dozens who had boarded on a boat, or a plane, without the documentation required to legally enter their target destination. Many of those they convince are exceedingly familiar with the risks.

“To get a visa to a western country you have to spend 60 lakhs, 70 lakhs, 80 lakhs to a proper agent, and even then it’s not sure,” said one Jaffna man who’d travelled to Australia by boat before being swiftly returned. “Who has money to spend that much? Only rich people. Better to get 15 or 20 lakhs together and try this way. Anyway we are screwed in this country.”

The first call from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent Venuja into a daze.

“S. Kiritharan is your husband, correct?” the lady on the line had asked. “He’s been admitted to hospital. We need you to send his birth certificate.”

He had been in touch just a few days prior. The family had video called him while he was in the Vietnamese government facility at Vung Tao, and he’d seemed in decent spirits, though a little anxious about what was going to happen.

“He and another man in the camp have drunk a lot of hand sanitiser,” the lady at the foreign ministry had told Venuja.

“But the lady at the ministry told me Kiri was 80% ok, and that the hospital needed the documents to treat him,” Venuja says.

Several fraught days later, in which the family phoned desperately for updates and got little by way of response, Venuja received another call. This one made her fall to the ground. The doctors had not been able save Kiritharan; he had died of poisoning in a Vung Tau hospital, 37 years old.

Clearly distraught, fresh trauma was heaped on the family when news outlets began to report that Kiritharan had died by suicide. Venuja refuses to believe this.

“He is not the kind of person who would do something like this… not for debt issues.” For the first time in our hours-long conversation, Venuja becomes emotional. “Yes, there were serious debts. We were under so much pressure before he left that I was the one who asked whether we should kill ourselves.”

She thinks he ingested sanitiser as a replacement for alcohol, failing to account for its toxicity. “I’m not going to lie, Kiri used to drink here. But even if he drinks he doesn’t come and fight with the family. It won’t even show that he has drunk; he would be on his own. Not sure whether they were trying to frame him as a drunkard.”

According to the International Organization for Migrants (IOM), the facility in which Kiritharan and the other migrants were accommodated was comfortable, its residents lacking for little in the way of basics. “It wasn’t like a detention camp by any means,” says Minoli Don, the Head of Protection of IOM’s Sri Lanka outfit. Don had flown to Vung Tao soon after the migrants had made landfall there, to brief them on their options, and assist with whichever course of action they chose. “They could walk around and there was a degree of freedom. The Vietnam government has been good.”

Whatever the circumstances of his death, the Sri Lankan government was largely unsympathetic. When Venuja and her brother visited the kachcheri to figure out next steps, they were told it would cost three million rupees to repatriate his body. As Kiritharan had attempted an illegal migration, no government assistance would be forthcoming, they were told.

“The government kept calling us to ask how much money we had collected, and we had to give updates.” As Kiritharan’s story had by now generated some media attention, the family raised the money through donations.

“We could not accept that his body would be buried in another country; his family is here only.” They buried him in Chavakachcheri.

Now, Venuja makes a little money making large funeral garlands for hearses. Thankfully, many of their debts to private institutions were forgiven, after their plight became public. Though the state-owned Bank of Ceylon had not been so clement. “We still owe about 1.3 lakhs to them,” she says.

Venuja sounds determined as she speaks of somehow educating her four children well. But she seethes when she recounts her brushes with the Sri Lankan government. “I have a lot more I can say about this. But If I say all that, my brothers who are looking after me now might get into trouble also.”

The best she can do is to fashion a life out of the debris.

*Sanju is not his real name. It was changed, upon his request, to protect his identity.