by T. Sabaratnam, October 27, 2003

Volume 1, Chapter 15

Original index of series|

Original Vol. 1, Chapter 16

Chat Session

Now that we have progressed to some extent we must start talking.

Talking to the readers is one of the facilities the internet offers; we can talk as we progress.

The purpose of this session is not to get bouquet or brickbat from my readers.

The real purpose is to correct errors, draw out more information about Pirapaharan and to present him to future generations as the real genius he is.

My intention is not to incorporate the information I gather in these chat sessions into my series. These sessions will run parallel to this series and could serve as seed material for future researchers and authors. Pirapaharan is a phenomenon, one of world’s greatest guerrilla leaders and freedom fighters, who has to be written on, analyzed and commented.

To date I have received three comments and I will start with the third.

Ambalavanar Sellathurai from Canada has pointed out a serious slip I had made.

I am reproducing his e-mail:

“Sir,

In Chapter 14 of the ‘Pirapaharan’ biography by T. Sabaratnam, it is stated that Thangathurai had recited Saint Manikkavasagar’s prayer, ‘Nam Yarkum Kudiyallom’and the saint’s sculpture is also depicted. This prayer is by Saint Thirunavukkarasar (Appar) and not by Saint Manikkavasagar. A correction is needed please.”

Appar is the first of Tamil Hinduism’s four saints – Appar, Suntharar, Thirugnasampanthar and Manikkavasagar. I am a Hindu. These names were drummed into my head. I learnt it without getting the famous “kuttu” of our days. I don’t know how I made that error. I regret it and it stands corrected. I have been a journalist since January 1957 and to me facts are sacred.

The first comment was from the editor of Sangam. This portion is from his letter:

“Yesterday I met a gentleman at the Sangam committee meeting who has been following your series on Pirapaharan closely. His first question was, “Is this going to be published as a book when it is finished?” He then went on in detail about how much he enjoyed reading it. He said it was an unbiased, factual, articulate and thorough. He said that it made one feel like one was right there in the middle of the events. The person in question says that he is very much looking forward to reading more as the chapters come out and he is recommending it to all his friends.

It seems this person rode on some bicycle trip as a young man with Pirapaharan – it sounded like to some meeting or protest, I did not catch which one – and reading your article about these events evidently brought back many memories to him of that time.”

While thanking that person who spoke to the Sangam editor I request him to write about it. We know that Pirapaharan rode in a cycle throughout the length and breadth of the Jaffna peninsula to acquaint himself with its roads, lanes and by-lanes. He cycled to political and protest meetings. An account of that trip and the conversation they engaged in would be useful. I request him to write about it. He can leave his identity out if he prefers.

The second letter is from a chemistry student from Carleton University in Canada. Excerpt from his letter:

“I really thank Sabaratnam because I got lots of information via this article, and also his writing style also excellent.”

He has promised to post this series in his university Tamil Sangam’s web page.

I am pleased. Others too can follow that example.

I expect and hope many more will write. They can send their comments to “Editor Sangam,”

Thank You

T. Sabaratnam

___________________________________________________________________

Two Golden Rules

In the second half of 1978, an intense intellectual debate raged among Tamil militant groups in Jaffna. The issues were individual terrorism and robbing banks. Marxist-oriented militant groups were condemning these actions as “immoral and anti-social.” Killing individuals does not make a revolution, they argued. Robbing banks was stealing people’s money.

People must be mobilized for a revolution to take root and society made to sustain the uprising.

Supporters of the militant group EROS initiated the debate. Its founder-leader, Ratnasabapathy (Ratna to friends and colleagues), was in Jaffna during that period. He had already undergone weapons training in Lebanon. His dream was more theoretical and extensive. The goal of militancy had to be a proletariat uprising which included the Indian Tamil workers of

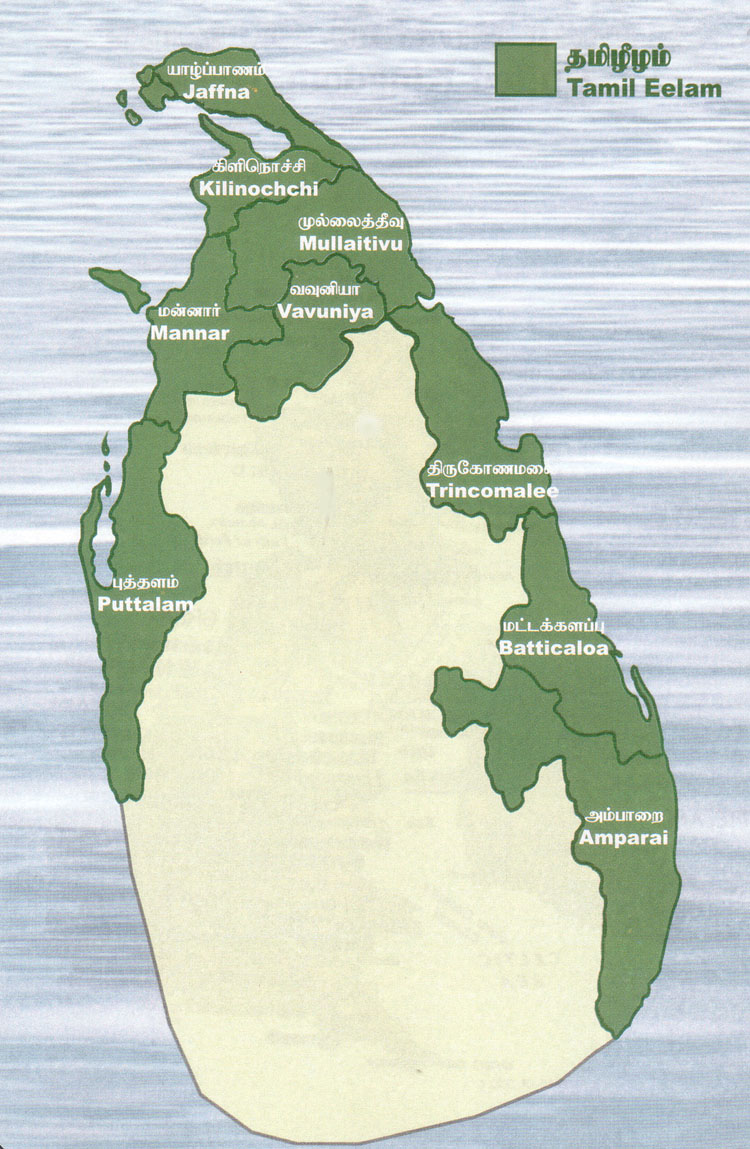

the central hills. He had brought with him a map of Tamil Eelam, which included the northern, eastern and central provinces.

Pirapaharan, a down-to-earth pragmatist, differed. He differed not only about the extent of Tamil Eelam territory, but also about the theoretical base of the revolution. Tamil Eelam should comprise the north and east of Sri Lanka, the historical area in which the Tamils lived. The central hills formed the historical homeland of the Kandyan Sinhalese. His world-view was not Marxist. He never spoke about the workers or the working class or a classless society. His concern since childhood had been the Tamil race. Tamils should not be a subject race. They should live in dignity, safety and security. They should not be terrorized by the Sinhalese mobs or by the armed forces.

His concern for socialism was limited to the creation of a casteless society among the Tamils and little more. He viewed the caste system as a factor that impedes the Tamil struggle. The caste system harmed Tamil unity and hindered the building of a strong, armed group.

A Jaffna University professor once told Pirapaharan that the people should be politicized before taking to the gun. Pirapaharan dismissed him with a wave of his hand: “What politicization? What the people need is action. We have to do some action first. People will follow us,” he said. That was what he did. That was his mode of struggle. Hit back. Hit back hard. Hit back repeatedly, ceaselessly. The people will be with you.

He drew two golden rules from this position: Wrest the weapons from your enemy and rob the money needed to finance your struggle from the enemy. The LTTE wrested most of its weapons from the police and the army. Pirapaharan teaches his cadres that getting the weapons is the major target of any operation. In the initial stage of the struggle, the LTTE took the major portion of its funds from the two state banks: Bank of Ceylon and the People’s Bank.

Tinnaveli Bank Robbery

The Tinnaveli Bank robbery was planned based on Pirapaharan’s ideas of how to mobilize people and how to develop his armed group. Pirapaharan wanted a major bank robbery to follow the spectacular 7 September plane blast that attracted international attention. It took him over a month to get ready. Snatching the sub-machine gun from the police officer on guard was to be the first act. He selected Sellakili for the task. He was appointed the leader of a six-member group which included Pirapaharan himself. Sellakili befriended cashier Sabaratnam who worked in the Tinnaveli branch of the People’s Bank. Sabaratnam told Sellakili that People’s Bank branches usually deposit their collections on Fridays with their head office in Jaffna. The money would be neatly packed in suitcases and kept in the chief cashier’s room to be transported to Jaffna around noon. He provided the sketch of the bank including the passages. The manager and his eight assistants would be present. Sellakili went to the bank and observed the set up.

Boundaries of Tamil Eelam. courtesy TamilNation

The group raided the bank, which was outside Jaffna city limits, on 5 December 1978, an hour after it opened. Sellakili went to Police Constable Kingsly Perera who was sitting on a chair near the gate holding his sub- machine gun. Sellakili pounced on him, wrested the gun from him and shot him with it. Reserve Police Constable Satchithananthan who was standing on the other end of the gate started running. Sellakili shot and killed him too and kept guard at the gate.

Pirapaharan and the other four herded the nine employees into the manager’s room and dumped the suitcases into gunny bags. They warned the employees to stay where they were till they had made their getaway. While they were getting out with their loot, a jeep from the Kopay police came by by chance. The Kopay police inspector had sent Reserve Police Constable Jayaratnam to cash a cheque for him. Sellakili opened fire on Jayaratnam as he got down, the others dumped the driver out and they left the bank in the police vehicle. Jayaratnam escaped with injuries.

LTTE had pulled off a major bank robbery, had escaped with a sub-machine gun, their second, and Rs. 1,180, 000/-, a big amount in those days.

Cashier Sabaratnam who helped the Tigers is now the finance chief of the Vanni administration. He was once known as Ranjith Appa, but now he calls himself Thamilenthi.

Talented Youths join

Thamilenthi joined the LTTE after the daring Tinnaveli Bank robbery, proving Pirapaharan’s position that action, mindcapturing action, would bring in cadres and supporters. Talented youths were drawn to the LTTE soon after its formation.

As pointed out earlier, Baby Subramaniam Ilankumaran joined soon after the LTTE was formed. He was involved in the Air Lanka plane blast. Kumrappa and Pandithar joined in 1977. Kittu, Mahattaya and Raghu joined in 1978. All of them were able and very successful commanders. Except for Baby Subramaniam, who is now in charge of education in the Vanni Administration, and Mahattaya, who was executed for betrayal, the others were martyred and are remembered fondly.

Kittu, Mahattaya and Ragu joined the LTTE soon after the AVRO blast and rose to responsible positions rapidly. They were all from Valvettithurai. Kittu was a relative of Pirapaharan and was inducted by him. Kittu, whose real name was Sathasivampillai Krishnakumar, studied at Chithampara College. His father owned a printing press in Nelliyadi and was a strong supporter of the Federal Party and an ardent follower of Thanthai Chelva. So was Kittu’s mother, Rajaledsumi. Kittu’s parents took part in the 1961 satyagraha before the Jaffna Secretariat and they carried the one-year-old toddler with them. Kittu, the youngest, was born on 2 January 1960. His parents, wedded to Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence, had named their eldest son

Gandhithasan, who is living now in India. Kittu, the fourth, and the two girls in between, died under tragic circumstances.

Rajaledsumi, in her old age, is still working to uplift downtrodden women.

Krishnakumar was christened Venkat, which became Venkat Anna and then Kittu Anna. He was given weapon training by Pirapaharan and was ranked with Pirapaharan and Kalapathy, who took part in Duraiappah’s murder, as top marksman. He 1961 Demonstration outside Jaffna Secretariat Alfred Duraiappah went with Pirapaharan to Tamil Nadu in 1979.

Mahattaya’s real name was Gopalasamy Mahendrarajah. He was born in 1956 in Point Pedro east and studied at Chithampara College. Pirapaharan also trained him. He rose to be the Deputy leader and functioned as Commander of Vanni. His rivalry with Kittu was the cause of his downfall. Ragu wanted to join the police service but was rejected because he was from Valvettithurai. Then he joined the LTTE.

Pirapaharan spent most of his time training his cadres and collecting money and weapons. He concentrated on raising a group of dedicated, highly motivated cadres of unimpeachable character and discipline and unquestionable loyalty. Discipline and loyalty, he argued, were the foundation of a successful guerrilla outfit.

Tamil Solidarity

Jayewardene was incensed by the Tinnavely Bank robbery. He called an urgent meeting of the Inspector General of Police Stanley Senanayake and Army Commander Lt. Gen. Denis Perera. The army commander took with him Brigadier Cyril Ranatunga, Commander, Western Command headquartered at Panagoda. Jayewardene told them: This simply cannot go on. This has to be stopped. I don’t know what you are going to do but you must stop it.”

Police and army chiefs suggested the strengthening of the law. They said the special law enacted to ban the LTTE was not sufficient. Jayewardene readily agreed to do it and ordered his secretary, Manikdiwela, to get the Attorney General and the Legal Draftsman to prepare an appropriate law. The Army Commander said he wanted to place Brig. Ranatunga in charge of the operation.

Brig. Ranatunga was given the task of apprehending the militants in January 1979. His first act was to ask Captain Sarath Munasinghe of the Army Intelligence Unit to set up within two weeks an Intelligence Unit in Jaffna to help in his operations. He set up an office at Palaly Army Camp which drew maps of all the vulnerable places in the Jaffna peninsula including Valvettithurai. Brig. Ranatunga was appointed Jaffna Commander in February.

While preparing militarily to deal with Tamil militancy, Jayewardene continued his political game of weakening the Tamil community and promoting a cleavage between the TULF and the militants. His move to draw the TULF into the government structure through the district minister scheme failed to yield quick results. Conscious of the growing youth pressure against it the TULF was reluctant to give a positive response. So, Jayewardene told Thondaman on 2 August, during a chat, about his scheme and his readiness to offer three of the 25 district ministerships to the TULF.

“I have told Amirthalingam about my scheme. Did he tell you anything about it?” Jayewardene asked Thondaman innocuously.

Thondaman asked Amirthalingam about it when he met him the next day. Amirthalingam said they were considering Jayewardene’s offer, but had not come to any conclusion. Thondaman told Amirthalingam that, if the TULF decided to accept the offer, one of the three posts should be given to him.

The next day, 4 August, Jayewardene asked Thondaman whether he spoke to Amirthalingam about the district minister scheme. Thondaman replied that he had told Amirthalingam that, if they decided to accept, one of the posts should be given to him.

Jayewardene seized the opening. “Will you join if I give you one?” “What is the use of a district ministership?” “Will you join the cabinet?” “If you invite me.” “I am inviting you. Will you join?” Thondaman accepted the invitation, but asked for time carry his trade union, Ceylon Worker’s Congress (CWC), with him. Jayewardene had scored a major triumph. He had got a section of the Tamil community to his side. He had weakened the Tamil struggle to that extent.

Jayawardene was keen to get the TULF also into his fold. That would help him to show to the world, especially the donor community, that he was a just and fair ruler who looked after the minority communities well.

The TULF was in a fix. Many members in the TULF parliamentary group favoured accepting the posts, however the youths were revolting against this action. The TULF politbureau decided to accept the district ministries if five were given.

Amirthalingam asked Jayewardene for the district ministries of Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu, Vavuniya and Mannar, the five districts in the northern province. Jayewardene was prepared to give only three posts, so the TULF dragged its feet.

Jayewardene announced the names of 24 district ministers on 5 October. He kept the post of the district minister for Jaffna vacant and announced that that had been reserved for the TULF. Since the TULF refused to accept it, the president appointed Ukku Banda Wijekoon, a UNP member of parliament from the Kurunegala district, for that post. The government appointed Vaithilingham Duraisamy, an opponent of the TULF, as secretary to the district minister.

Jayewardene, meanwhile permitted Cyril Mathew to continue with his anti- TULF, anti- Tamil campaign. From anti- Tamil speeches, he progressed into publishing anti- Tamil pamphlets and booklets. They were targeted, in a systematic way, to instigate the Sinhala people against the Tamils. They were ghost written by a group of officials Mathew had gathered around him in his Industries Ministry. They were published and distributed by the Ministry of Industries as government publications.

The first booklet of that series was titled “Sinhalese! Rise to Protect Buddhism.” It was a collection of speeches Mathew delivered in 1979 which contained the photograph of a map EROS had prepared. It showed the north-western coast up to Chilaw and the Tamil majority areas in the hill country as part of Tamil Eelam. As the reporter covering the Industries Ministry for the Daily News, I was with Mathew at the Puttalam Rest House when the first copies of the booklet were delivered to him by his ministry officials. He was on an inspection of the Puttalam Cement Factory. He gave me a copy of the booklet and showed me the map and said: “See what your people are claiming. Is it fair?’

In that booklet, Mathew argued that the northern and eastern parts of Sri Lanka were ancient Sinhala territory. They were originally ruled by Sinhala kings and Sinhalese had lived there. Tamils had invaded those areas during the beginning of the second millennium and had pushed the Sinhalese to the south. Tamils, who were now trying to claim the north and the east as their traditional homeland, were now trying to destroy all historical evidence, he charged. He organized the distribution of that pamphlet through Buddhist temples.

The second booklet instigated the Sinhala people to boycott Tamil shops. It accused the Tamils of holding the Sri Lankan economy by the neck. It said, “the wholesale and retail trade” was completely in the hands of the Tamils. It urged the Sinhalese to destroy the dominance the Tamils had in the wholesale trade in the Pettah market in Colombo. It also called upon the Sinhalese to patronize the Sinhala shops. That pamphlet was distributed by the Sinhala traders.

Another pamphlet targeted Tamil plantation workers. It warned that the Indian Tamil workers had grown into a threat to “Buddhism and Sinhala culture” and pointed to the building of Hindu kovils as an immediate threat. It warned, “Buddhism and the up-country villages will all vanish” from the historical lands of the Kandyan territory. This booklet was distributed through the Buddhist temples in the hill country.

The fourth pamphlet, “Who is the Tiger,” tried to show that all Tamils who spoke of their rights were Tigers. It propagated the Mahawansa theory that Sri Lanka is a Sinhala- Buddhist country and the Tamils were invaders who belonged to Tamil Nadu in India. Tamils should either go back to Tamil Nadu or live at the mercy of the Sinhala- Buddhists. This booklet was distributed by the traders, Sinhala organizations and Buddhist temples.

While creating the ground for Sinhala onslaught on the Tamils, Cyril Mathew also took upon himself the cause of the Sinhalese who resented the reversal of Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s university admission policy by the new government.

Sinhala extremists, especially academics and school teachers, opposed the new government decision announced in its Statement of Government policy of 4 August 1977. They did not want to forgo the advantage Sinhala students had derived since 1972. Sinhala nationalist groups declared their opposition to reverting to the merit system. A return to the merit system, they argued, would result in Tamils outnumbering the Sinhalese in the much sought-after professional studies of

medicine and engineering. The one- day token strike the secondary school children called for February 1978 was averted by the government by the closure of the schools on that day and by the arrest of the organizers.

Mathew, who was building himself as the leader of the Sinhala nationalists, took up the university admission issue in parliament on 11 December 1977, repeated the earlier Sinhala accusation that Tamil examiners over-marked the scripts of Tamil students and said he had definite proof which he intended to produce before the media the next day.

Sivasithamparam repeated his earlier reply and said the Tamils would not take lying down the charge that they were cheats.

Mathew held a media briefing the following day, 12 December, at the Industries Ministry. I covered it for the Daily News.

Prof. P. P. G. L. Siriwardene, Professor of Chemistry, Colombo Campus of the University of Sri Lanka, was present as a special invitee. Mathew produced two biology answer scripts of two Tamil students who sat for the GCE Advanced Level examination held in 1977 and alleged two marks had been given in excess over the allotted marks for a question on the life-cycle of a mosquito.

He said, “Marks had been awarded to Tamil students in a manner that was unworthy of civilized people. Tamil examiners had been dishonest and as a result a large number of Sinhalese students had been deprived of the opportunity of getting into university. It is a conspiracy practiced since 1968.”

Mathew, when questioned by the media, failed to answer how he got those confidential papers. However, the Sinhalacontrolled English and Sinhalese media, then mostly state-controlled, printedwith glee the story as their leads.

Mathew followed the press conference with another of his vicious pamphlets, titled “The Diabolical Conspiracy”, which accused Tamil examiners of awarding high marks to Tamil students to make them enter the university in higher numbers.

He tried to make out that this was a Tamil national conspiracy. He tried to show the matter as “a burning question …exploding within the hearts of Sinhala students, parents and teachers.”

The government then announced the district quota scheme. District quota system allotted 30 percent of the university seats on merit, 55 percent on the basis of population of each district, and the balance of 15 percent to backward districts.

It looked as if the Jayewardene government had made use of Mathew’s charge of cheating as a smokescreen to introduce the district quota system for university admission. It could have done made the introduction without hurting the Tamils’ pride, but Sinhala politicians and the media were insensitive to the feelings of the Tamils. That was one of the major M. Sivasithamparam, MP

incidents that alienated the Tamils, planting in their hearts Tamil national consciousness and building in them the feeling of solidarity.

Three weeks before this calculated Mathew insult a natural disaster that struck the eastern coastal belt in Batticoloa and Mullaitivu districts also roused and kindled the Tamil National consciousness. A cyclone accompanied by a massive tidal wave flattened the coastal areas and dissipated over Polannaruwa. Sinhala officers manning the government departments and agencies diverted local and international aid to less affected Sinhala areas in Polannaruwa, thus depriving the needy Tamil areas of assistance. Groups of Sinhala thugs blocked the roads and diverted the lorries carrying foreign assistance from Tamil areas to the Sinhala areas.

Tamils of the north boiled with anger when they learnt about the government’s indifference and Sinhala thuggery and organized their own disaster relief. Jaffna University students, social and religious organizations and militant groups played the lead role in this movement to help Tamil brethren. Among the Tamil militant groups, the LTTE and EROS played a significant role. They went in sizable groups, lived in the damaged eastern villages and helped the villagers to rebuild their houses and their lives. One of them was a youth named Inbam. His real name was Viswajothi Erattinam. He was arrested, tortured, killed and his body was thrown on the Pannai Bridge when he returned to Jaffna after Jayewardene turned the northern peninsula into a killing field in the latter half of 1979. That story will be told later.

Tamil distrust in Sinhala government officers hardened when their conduct was exposed in parliament and the Tamil press.

Quality sarees India gifted to be sent to the Tamils of the east were sold to Colombo public at cut-rate prices! When queried the officers answered that the money so raised was spent on disaster relief. Tent material was left to rot in government buildings. ‘Tamils have to look after themselves’ was the feeling that grew among the Tamils, even among those living in Colombo. This made them join the relief effort.

The Jayewardene government, through its commission and omission, created during 1978-78 an environment conducive for the growth of Tamil militancy. Jayewardene, in particular, was keen in weakening the TULF, which even at that time enjoyed considerable influence among militant groups especially the LTTE and the TELO. Pirapaharan, Uma Maheswaran, Thangathurai, Kuttimani, Jegan and others listened and obeyed the Amirthalingam- Sivasithamparam group’s advice.

Jayewardene’s strategy was not to make use of the TULF influence to control and contain Tamil militancy politically, but to drive a wedge between them.

Jayewardene believed in violence. He decided to also give the Tamil militants the same medicine he administered to Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s supporters – state violence.

Next: Chapter 17: Sinhala- Tamil Tension Mounts

To be posted on Nov. 3

###

Volume One

Chapter 1: Why didn’t he hit back?

Chapter 2: Going in for a Revolver

Chapter 3: The Unexpected Explosion

Chapter 4: The Tamil Mood Toughens

Chapter 5: Tamil Youths Turn Assertive

Chapter 6: Birth of Tamil New Tigers

Chapter 8: First Military Operation

Chapter 9: TNT Matures into the LTTE

Chapter 10: The Mandate Affirmed

Chapter 11: The Mandate Ratified

Chapter 12: Moderates Ignore Mandate

Chapter 13: Militants Come to the Fore

Chapter 14: The LTTE Comes into the Open

Chapter 15: The Ban, J.R.’s Gift

Chapter 16: Wresting Weapons from the Enemy

Chapter 17: Sinhala-Tamil Tension Mounts

Chapter 18: Tamils Lose Faith in Commissions

Chapter 19: Balasingam Enters the Scene

Chapter 20: Jaffna Turned Torture Chamber

Chapter 21: The Split of the LTTE

Chapter 22: The Burning of the Jaffna Library

Chapter 23: Who Gave the Order?

Chapter 24: Tamils Still Back Moderates

Chapter 25: Parliament Discuses Ways to Kill Amir

Chapter 26: The First Attack on the Army

Chapter 27: Amirthalingam Taken for a Ride

Chapter 28: RAW Meets Pirapaharan

Chapter 29: The Indian Interest

Chapter 30: LTTE Guerrillas in Action

Chapter 31: The Death of the First Hero

Chapter 32: The Return of Pirapaharan

Chapter 33: Knocking Out the Base

Chapter 34: Tamils Follow Militant Leadership