by T. Sabaratnam, December 11, 2003

Volume 1, Chapter 21

Original index of series|

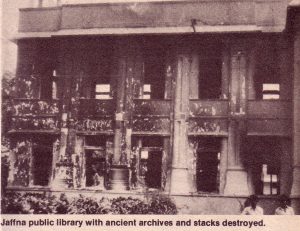

Jaffna Public Library

President Jayewardene thought that Brigadier Weeratunga’s Operation Round Up had sufficiently weakened Tamil militants and decided to consolidate his position .”through political process by implementing the proposals of the Presidential Commission on District Development Councils, which he had appointed on 8 July 1979 under the chairmanship of the former Chief Justice Victor Tennakoon. The Commission submitted its report in April 1980.

The Tennakoon Report accentuated the growing rift between the TULF leadership and the militant youth. The youth wing of the TULF, which was unhappy about the failure of the leadership to oppose the enactment of the Prevention of Terrorism Act in July 1979, revolted when the District Development Council (DDC) report was published . They scribbled on walls and roads in the north the slogan: Is this the Eelam you promised?

Mavai Senathiraja, who was released from prison when emergency lapsed on 27 December 1979, led the revolt which was joined by the Suthanthiran group. Suthanthiran, meaning ‘Independent,’ the Tamil weekly founded by Thanthai Chelva to propagate the ideals of the Federal Party and of the TULF after its formation in 1976, was run by his youngest son S. C. Chandrakasan after Chelvanayagam’s death in 1977. The paper ran a hard-hitting lead story on 21 April 1980 calling upon the TULF to launch the promised liberation struggle instead of fooling the Tamil people with the fake DDCs.

Suthanthiran was at that time edited by Kovai Mahesan who abbreviated the name of his birthplace Kopay to Kovai and his name Maheswara Sharma to Mahesan . He was very popular among the people through his hard-hitting political column, Arasiyal Mada!, which means Political Epistle. He ridiculed the DDC. Neither the TULF nor Amirthalingam had any control over Suthanthiran though it was the TULF’s official organ because Chandrakasan did not interfere with the political line taken by Kovai Mahesan . It was believed in TULF circles, then, that Chandrakasan actively supported Kovai Mahesan line .

Amirthalingam launched another weekly named Uthayasooriyan (Rising Sun) to counter Kovai Mahesan ‘s attacks. It called itself the official organ of the TULF. It carried a special column, Paravaikale Paravaikale, (Birds, Oh Birds) in which Amirthalingam replied to Kovai Mahesan. Both columns amused profusely the Tamil reading public.

An example:

Kovai Mahesan wrote:

Soru Vendam

Suthanthirame Vendum

Palam Vendam

Eelame Vendum

Its meaning:

We don’t want rice

We want freedom

We don’t want bridges

We want Eelam

Amirthalingam replied:

Sorum Vendum

Suthanthuiramum Vendum

Palamum Vendum

Anthap Palathai Vaithe

Eelathai Uruvakkum

Vivehamum Vendum

Its meaning :

We want rice

And we want freedom

We want bridges

And the wisdom

To make use of the bridges

To attain Eelam

At the instance of Mavai Senathirajah and Kovai Mahesan’s group, which comprised youth agitators like Eelaventhan and Dr. S. A. Tharmalingam, the Tamil Youth Front (TYF) passed a resolution on 29 April 1980 threatening to convert itself into a liberation movement if the TULF failed to do so before 31 May . Mavai resigned from the TULF accusing it of inaction .

The clash came into the open on May Day, 1980 which the TULF observed with the traditional rally. At that rally TYF members shouted slogans against the TULF leadership , Amirthalingam in particular. ” When are you setting up the promised Constituent Assembly?” “Resign your seats and launch the freedom struggle .” “Power corrupts even the Thalapathy .”

Amirthalingam was worked up. He delivered an emotional speech at the public meeting that followed the rally . He made a scathing attack not only on the TULF dissidents, but also on th e militant groups. He quoted the popular Tamil proverb to say that the militants would not achieve anything worthwhile The adage reads:

Sirup illai Velanma i Veedu Vanthu Serathu

He also said, ” You are roaming about in small groups. You are courting disaster.” Sivasithamparam, TULF president, defended Amirthalingam. He asked the dissenters, “Can you achieve anything by getting rid of Amirthalingam?”

Amirthalingam Jayawewa

The dispute intensified after Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa tabled the District Development Councils Bill in parliament on 8 August 1980. The youths demanded its rejection. They wanted the TULF to oppose it in parliament and launch the freedom struggle. The TULF pa rl iamentary group differed. It wanted to support the bill and help Jayewardene implement it.

Jaffna Public Library after burning

The TULF General Council met at Vavuniya a week later to consider its stand on the bill. Opening the discussion in that 10- hour meeting Amirthalingam proposed that they support it .. “Calling it a historic piece of legislation, Amirthalingam gave

three reasons for its acceptance . Firstly, it wsould start the decentralization process countrywide . It would involve the people in the development process . Secondly , whether the TULF accepted it or not the government with its massive majority in parliament would enact it. It would be better to be part of the process than be its opponents . Thirdly, if the TULF accepted the bill and implemented the law, they could promote the economic development of the Tamil districts . If they rejected it, the economic neglect of the Tamil areas would continue .

There was strong criticism . Opponents said that was too little, too late; that the law was weaker than the Regional Council Bill prepared by the Dudley Senanayake government a decade ago which the youths had called “a glorified municipal counci l. ” They pointed out that the law- making and ta xing powers of the DDCs were limited and were dependent on the goodwill of the government . They predicted that the Jayewardene government would make use of the DDCs as a showpiece to the international community and would not allow it to work . Jayewardene would only use the DDCs to tell the world that the Tamils were with him.

Dissident youths staged a satyagraha outside the Vavuniya Town Hall where the meeting was held . They sat under a banner which read: Reject the Bill which distracts us from our goal. When Amirthalingam emerged from the meeting which decided to support the DDC Bill around 9 p.m., youths swarmed him shouting derisively: Amirthalingam Jayawewa . It meant that Amirthalingam had won a victory for the Sinhalese . Eelaventhan who organized the satyagraha walked up to Mangayarkarasi, Amirthalingam’s wife, prostrated before her weeping and said: Your husband had betrayed the struggle . Good bye. Eelaventhan, whose real name was Kanagenthiran, had been associated with the TULF and one of its main constituents, the Federal Party, since its salad days.

Eelaventhan’s adieu sealed the split in the TULF. Kovai Mahesan’s group left the TULF and they formed a new party, the Tamil Eelam Liberation Front (TELF). Dr. Tharmalingam was elected it leader and Eelaventhan its secretary .

Pirapaharan was in Sri Lanka during that time to reconstitute and revitalize his group . He was determined to stage a comeback . He was determined to build a guerrilla group loyal to him, a group that would do his bidding . He had decided that theoretical bickering, disputes about the mode and manner of the struggle and endless squabbling about the running of the organization would not take the freedom struggle forward. He adopted the practical approach adopted by Thanthai Chelva : sole leader, single decision-maker, single-minded commitment to the cause of freedom for the Tamils. Kittu, one of his deputies, in an interview to the LTTE’s official journal, Viduthalai Puligal had adverted to this. Pirapaharan had told him that Thanthai Chelva was able to negotiate agreements with prime ministers S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and Dudley Senanayake because he was the sole leader of the Tamils. If Thanthai Chelva had taken Tamil Congress leader G. G. Ponnambalam and C. Suntharalingam to the talks, it would have failed because the two clever prime ministers would have exploited the division among the Tamil leaders.

Uma Maheswaran

While engaged in picking active combatants absolutely loyal to him and dedicated to the cause of Tamil freedom to revive the LTTE, Pirapaharan continued to exert pressure on Uma Maheswaran to give up his claim to the LTTE. He also spurned the suggestion that he form a new organization saying that he loathed foregoing the LTTE’s history . “I would rather commit suicide rather than give up the LTTE’s history. It has transformed the Tamil struggle and has etched for itself a place in the minds of the people,” he is reported to have told the mediators .

Uma Mahesawaran finally yielded to the pressure from friends, in Sri Lanka, London and Tamil Nadu, gave up his claim to the LTTE’s name and inaugurated his own organization, the People’s Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE), carrying with him the load of hair-splitting Marxists and theoretical pundits who spent more time in debating than in action . Pirapaharan was thus freed of the burden of the debating disrupters .

Uma Maheswaran, to carve for his new organization a niche in the hearts and minds of the Tamil people, launched a series of daring strikes against the government and violently opposed the TULF taking part in the District Development Council elections.

Meanwhile, President Jayewardene took another step to entrench his rule. He got Prime Minister Premadasa to move a motion in parliament on 16 October 1980 to deprive Sirimavo Bandaranaike of her civic rights for seven years, thus removing her from the next presidential election, which he planned to contest . TULF opposed this action, arguing that the deprival of civic rights of a former prime minister who had ruled the country twice was a travesty of democracy.

Amirthalingam appealed to the government to drop that vindictive action . This earned for the TULF Jayewardene’s ire .

Pirapa’s interest in politics

Pirapaharan, though busy reviving the LTTE, which he won back after tremendous effort, kept abreast of these political developments. By instinct he is a political animal. He has said so, in many interviews. He has said that his interest in politics was what turned him into a rebel. The following quote is from his very first interview given to Anita Prathap in 1984.

Anita asked: At what point of time did you lose faith in the parliamentary system? What precipitated this disillusionment?

Pirapaharan: I entered politics at a time – in the early Seventies – when the younger generation had already lost faith in parliamentary politics . I entered politics as an armed revolutionary . What precipitated the disillusionment in parliamentary politics was the total disregard and callousness of the successive governments towards the pathetic plight of our people.

For Pirapaharan , it was the pathetic plight of the Tamil people, and the failure of democratic agitation to remedy the situation, that were the propellers for taking up arms . He always kept his ear to the ground and followed minutely all political developments and consulted knowledgeable persons to fathom its intri cacies .

V. Dharmalingam

Pirapaharan was in Jaffna when youths clashed with the TULF leadership about the acceptance of the DDCs. One morning he dropped in at V. Dharmalingam’s residence to find out about the govern m ent ‘s proposal. He was given a thosai breakfast, Dharmalingam ‘s son, Siddharthan, recalls. Pirapaharan showed Siddharthan his pistol. ” Bastiampi llai had this earlier, ” Pirapaharan told him. Siddharthan, who now heads PLOTE, recalls his father explaining to Pirapaharan the features of the DDCs. He told Pirapaharan that the DDCs would lay the foundation for a federal solution to the Tamil problem. “It would be the beginning of the establishment of an autonomous region for the Tamil people. Let’s accept it and work at it,” Dharmalingam told Pirapaharan .

Siddharthan recalls Pirapaharan intensely questioning his father . He asked him about the powers of the DDCs, its finances and whether it would have power over land and police. Dharmalingam admitted that the DDCs would be much weaker than the regional councils proposed under the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayagam Pact . ” Pirapaharan did not express any opinion . He was thoughtful,” Siddarthan recalls .

Pirapaharan was silent about his stand about the DDCs, but not the TULF youth wingers . Two actions of the TULF leadership heightened their wrath . The first occurred in February 1981. TULF MPs attended the Jaffna District Coordinating Committee meeting where Amirthalingam pledged the TULF’s cooperation to the government’s development effort . The second was the ir announcement to contest the DDC election fixed for 4 June 1981.

The youth revolt against the TULF leadership, non-violent till then, turned violent on 16 March 1981. On that night Amirthalingam, Dharmalingam and Rajalingam were at dinner at Valve tt ithurai . Three youths damaged Dharmalingam ‘s jeep . Two days later Rajalingam;s jeep parked at Arasady road in Jaffna was smashed. A few days later Point Pedro MP K. Thurairatnam was attacked while returning after addressing a public meeting in Mannar.

Neerveli Bank Heist

Cash-strapped TEL0 made use of this rising public fury to rob a private pawn-broker at Kurumbachetty on 7 January 1981, thus inaugurating a fresh bout of violence. Alerted by the cries for help of the owner of the pawn shop and his assistants, the public gave chase to the ” robbers ” without realizing they were “boys . ” The “boys” opened fire killing civilians Aiyadurai and Kulendran. On 16 March the TELO- Pirapaharan alliance carried out its first joint operation. Pirapaharan and Kuttimani cycled to Kalviyankadu on the outskirts of the Jaffna city and shot dead Chetti Thanbalasingham , former president of the TNT, who had turned police informant . Chetti who was standing on the road, talking to a fr iend , was taken by surprise and could not lift his hand to pluck his revolver tucked in his waist band. He was shot point blank.

Nine days later, on 25 March 1981 , Kuttimani pulled off the sensational Neerveli Bank robbery, the biggest till that time in Sri Lanka. Having carefully studied the system the Neerveli branch of the People’s Bank employed to deposit its collection in its head office in Ja ffna , Kuttimani planned the robbery. Dressed as military personnel Kuttimani and his chosen gunmen waited in ambush for the cash-carrying vehicle on a lonely spot near Neerveli junction . As the vehicle approached one of the gunman jumped on to the road and cried ‘ Halt ‘ in Sinhala . The driver stopped the vehicle thinking they were military men. Kuttimani and his men shot dead the two policemen, Muthu Banda and Ariyaratne, and decamped with the five suitcases neatly packed with 7.9 million rupees in cash.

Nine days later, on 25 March 1981 , Kuttimani pulled off the sensational Neerveli Bank robbery, the biggest till that time in Sri Lanka. Having carefully studied the system the Neerveli branch of the People’s Bank employed to deposit its collection in its head office in Ja ffna , Kuttimani planned the robbery. Dressed as military personnel Kuttimani and his chosen gunmen waited in ambush for the cash-carrying vehicle on a lonely spot near Neerveli junction . As the vehicle approached one of the gunman jumped on to the road and cried ‘ Halt ‘ in Sinhala . The driver stopped the vehicle thinking they were military men. Kuttimani and his men shot dead the two policemen, Muthu Banda and Ariyaratne, and decamped with the five suitcases neatly packed with 7.9 million rupees in cash.

The government was shocked. Jayewardene was highly perturbed. His dream that Tamil militancy had been crushed with Operation Round Up had crashed . He presided over a top level security conference which decided to launch a massive hunt for the robbers, guard the coast to prevent them escaping to Tamil Nadu and to announce a one million rupee award to informants .

Kuttimani, Thangathurai and Sellathurai Sivasubramaniam (alias Thevan and Vellai Mama) were arrested on 5 April night at Manalkadu, a coastal fishing village in Point Pedro East, while standing on the sandy beach awaiting the boat arranged to ferry them to Tamil Nadu. Thangathurai, whom I interviewed during his trial in Colombo, gave this detail: We were dropped at the beach by Sri Sabaratnam. He told us that the boat would arrive around 11 pm. It did not come. Then we saw policemen walking towards us with guns outstretched, pointing at us. “Surrender,” they ordered. “We looked around . We saw we were surrounded . There was no way to escape. We raised our hands.” Kuttimani, while raising his hands, tried to pull out his revolver . He wanted to shoot himself . He was overpowered . The revolver went off, the bullet piercing his ear. “We were arrested, handcuffed and chained. We were airlifted to Colombo and taken to the Panagoda Detention Camp.”

“Do you suspect that someone had tipped the police?” I asked .

“That is the only conclusion that we could come to,” Thangathurai said.

He gave his reasons for his suspicion . The police party led by an inspector had parked their jeep far away and walked towards them without making any noise. There were six policemen and they advanced towards them in a circle so that they could prevent them from running away . They brought handcuffs so that they could tie them up. And the fact that the boat did not turn up at the arranged time was also suspicious.

“Do you suspect anyone?” I asked.

He did not answer. He smiled . “You will know alter we come out .” “Do you suspect the boatmen,” I probed.

He smiled.

“Who arranged the boat?” I asked . “Pirapaharan.”

“Do you suspect him?” I persisted.

He smiled again and added: “I cannot tell a pressman my suspicions. I will investigate the matter when I come out.”

He did not come out of the Welikade prison where he was in custody because he was killed a year after the interview, on 25 July 1983, on the first day of the prison massacre. So were Kuttimani and Thevan.

The security forces mounted a massive hunt for those who had robbed the Neerveli Bank . They knew it had been the work of TEL0. That hunt brought out again the genius in Pirapaharan. He beat the police in every move. He hurriedly shifted the arms to new hideouts. The police drew a blank when they raided the old dum ps. But they kept Pirapaharan on the run. He retreated to Vanni, living in the forest, sleeping inside thickets, often hungry.

Kuttimani and Jegan 1982

He returned to Jaffna very often, mostly in the nights, mainly to keep abreast of the events there. But he and TELO, whose leaders were arrested, kept a low pro file. TELO also suffered another blow on 26 April 1981 when Jegan (Ganeshanathan Jeganathan) was arrested on a tip-off. “This gave Uma, anxious to capture the imagination of the Tamil people, a field day. He teamed up with Suntharam (Sivasanmugamoorthy) and decided to sabotage the DDC polls . On 24 May A. Thiyagarajah, former principal of Karainagar Hindu College and former MP for Vaddukoddai, who headed the UNP list of candidates, was shot dead by PLOTE gunmen.

Jayewardene was advised by Thondaman and A. J. Wilson, who had assisted the President since 1978, not to field candidates in the northern province. “Let the Tamil parties fight it out,” Wilson told him. Jayewardene preferred to listen to the advice of the UNP organizers in the north, people like Ganeshalingam, Pullenthiran and others . He decided to show the international community that he enjoyed a following by winning at least one or two seats in 10- member Jaffna District Development Council. He wanted to do that by fair or foul means.

He sent two of his trusted ministers, Cyril Mathew and Gamini Dissanayake, to Jaffna to oversee the UNP campaign and assist in the conduct of the polls. Mathew went first, with his fleet of CTB busses packed with his thugs, and stayed at the Cement Corporation guest house at KKS . Gamini Dissanayake went later and stayed at Subhas Hotel in Jaff na. According to Wilson when Gamini met Jayewardene before his departure to Jaffna the President told him “have an eye on Cyril.” (Refer to Wilson’s article “President J. R. Jayewardene and the Sri Lanka Tamils” published in Lanka Guardian of 15 March 1995.) That raises the suspicion that Jayewardene knew Cyril Mathew might do something drastic.

The TULF, which ran an efficient election campaign despite the opposition of the youths, held its final propaganda meeting on 31 May at Nachimar Kovilady just outside Jaffna city along the Jaffna- KKS road. Jaffna’s mayor presided. The crowd was fairly huge. Four policemen, detailed to provide security, were seated in the rear on two benches. A group of PLOTE gunmen appeared from behind and fired at the policemen. Two of them, Sergeant Punchi Banda and constable Kanagasuntharam, were killed on the spot. Constables Usman and Kulasinghe were injured. This incident sparked another riot.

Vettivel Yogeswaran

About half an hour after the incident Jaffna police rushed a posse of policemen to the site of the incident. They burnt the temple, adjoining houses and two cars. Then they stopped the last bus returning from KKS, forced the passengers out and drove in it to the Jaffna bazaar. They burnt the row of shops on Hospital Street . Then they drove to Jaffna MP Vettivel Yogeswaran’s home, a kilometer away, set fire to his jeep, his friend’s car and to his house. Yogeswaran and his wife scaled the rear wall and took refuge in a neighbouring house. The policemen proceeded to the TULF head office at Main Street and set fire to it.

Yogeswaran raised the burning of his house in parliament a week later. He said : “Police came there to kill me. I am fortunate to be here alive.”

Mathew intervened. He said a police party went to Yogeswaran’s house as the police had got the information Yogeswaran was having a meeting with terrorists. The burning took place because the terrorists had fired at the police.

A delegation of the Colombo-based Movement for Inter- Racial Justice and Equality (MIRJE), in its report about the incidents, confirmed that the police went to kill Yogeswaran. It said: “It was fortunate that the MP was able to escape with his life for there is no doubt that the police came to kill him.”

The police orgy of violence continued on the second night, 1 June 1981. On that melancholy night Jaffna’s pride, the priceless library was burnt down.

Jaffna’s entire populace was awake that gloomy night watching helplessly the dark smoke that spiraled up and hung low covering the starry blue sky . They stared helplessly because the few who went out to dowse the fire were chased back by the police. Some eyes were tearful. Some eyes were closed, unable to bear the sight.

Jaffna Public Library 1981

One youth was defiant . He looked at the leaping flames with rage. His eyes grew red, bulged. His facial muscles stiffened . His heart beat faster.

He vowed revenge .

He muttered: Jayewardene’s men have made my task easier . This scar in the minds and hearts of the Tamil people is deeper than that of the Tamil Research Conference killings. No Tamil will ever forget or forgive this dastardly act .

The youth was Pirapaharan. He frothed with angry outside his hideout not far away from the burning inferno . Index to previous chapters

Next: Chapter 23: Who ordered the Burning? To be posted on December 17.

###

Volume One

Chapter 1: Why didn’t he hit back?

Chapter 2: Going in for a Revolver

Chapter 3: The Unexpected Explosion

Chapter 4: The Tamil Mood Toughens

Chapter 5: Tamil Youths Turn Assertive

Chapter 6: Birth of Tamil New Tigers

Chapter 8: First Military Operation

Chapter 9: TNT Matures into the LTTE

Chapter 10: The Mandate Affirmed

Chapter 11: The Mandate Ratified

Chapter 12: Moderates Ignore Mandate

Chapter 13: Militants Come to the Fore

Chapter 14: The LTTE Comes into the Open

Chapter 15: The Ban, J.R.’s Gift

Chapter 16: Wresting Weapons from the Enemy

Chapter 17: Sinhala-Tamil Tension Mounts

Chapter 18: Tamils Lose Faith in Commissions

Chapter 19: Balasingam Enters the Scene

Chapter 20: Jaffna Turned Torture Chamber

Chapter 21: The Split of the LTTE

Chapter 22: The Burning of the Jaffna Library

Chapter 23: Who Gave the Order?

Chapter 24: Tamils Still Back Moderates

Chapter 25: Parliament Discuses Ways to Kill Amir

Chapter 26: The First Attack on the Army

Chapter 27: Amirthalingam Taken for a Ride

Chapter 28: RAW Meets Pirapaharan

Chapter 29: The Indian Interest

Chapter 30: LTTE Guerrillas in Action

Chapter 31: The Death of the First Hero

Chapter 32: The Return of Pirapaharan

Chapter 33: Knocking Out the Base

Chapter 34: Tamils Follow Militant Leadership