by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 7, 2013

In the past 15 years or so, it has become a trend in Sri Lanka, for active journalists and pretending journalists, to promote themselves with real or fake awards for their services to the country. To the best of my memory, I don’t remember Gamini Navaratne (1932-1998) receiving any award for his journalism. Not many Sri Lankan journalists, however, can boast about a news feature written about him or her in the New York Times. Gamini Navaratne was an exception. Even if the ruling Sinhalese establishment and his journalist colleagues forget his professionalism, and treated him as a ‘traitor’ when he was alive, Tamils are duty bound to remember this courageous journalist. Navaratne breathed last on March 10, 1998, and this year marks his 15th death anniversary.

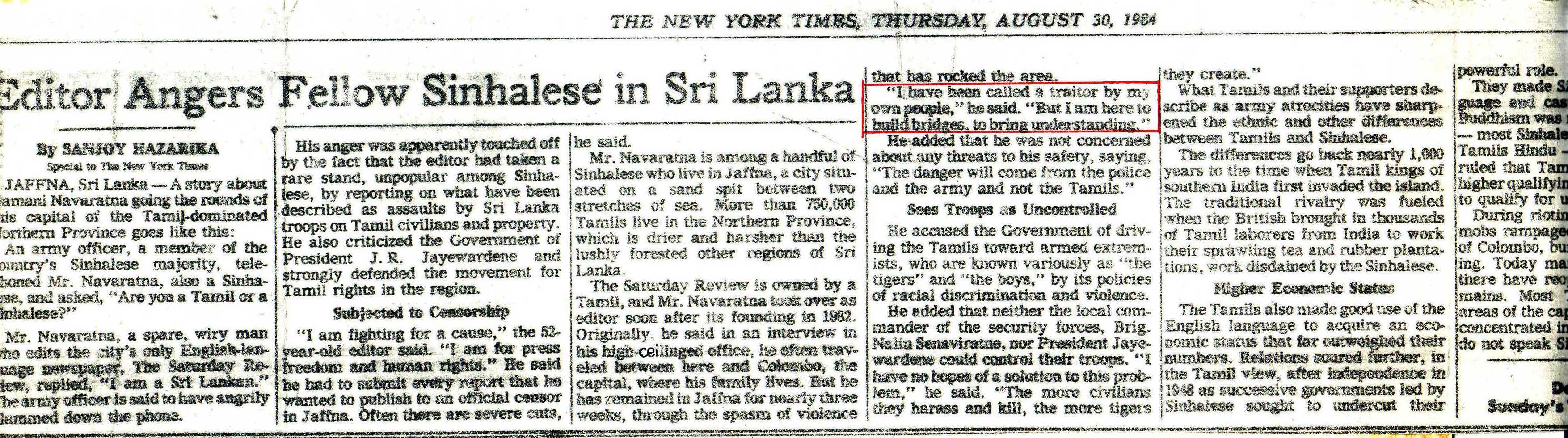

Though I never met or corresponded with Navaratne, his courageous services, despite all odds, to the concerns of Tamils as a whole was impressed on me by Prof. A. Sanmugadas (then affiliated to the University of Jaffna), when he visited Tokyo during the IPKF-LTTE war in 1988. As homage to the fearless and impartial spirit of Gamini Navaratne, I provide three of his contributions to Times of India daily between 1981 and 1984, which were in my collections, at the end. First, I provide below verbatim, the script which appeared in the New York Times of August 30, 1984, authored by Sanjoy Hazarika. The word ‘traitor’ in the subtitle was from Navaratne himself, as recorded by Hazarika.

New York Times item on Gamini Navaratne

“Jaffna, Sri Lanka – A story about Gamini Navaratna going the rounds of this capital of the Tamil-dominated Northern Provinces goes like this:

An army officer, a member of the country’s Sinhalese majority, telephoned Mr. Navaratna, also a Sinhalese, and asked, “Are you a Tamil or a Sinhalese?”

Mr. Navaratna, a spare, wiry man who edits the city’s only English-language newspaper, The Saturday Review, replied, “I am a Sri Lankan.” The army officer is said to have angrily slammed down the phone.

His anger was apparently touched off by the fact that the editor had taken a rare stand, by reporting on what have been described as assaults by Sri Lanka troops on Tamil civilians and property. He also criticized the Government of President J.R. Jayewardene and strongly defended the movement for Tamil rights in the region.

“I am fighting for a cause”, the 52- year-old editor said. “I am for press freedom and human rights.” He said he had to submit every report that he wanted to publish to an official censor in Jaffna. Often there are severe cuts, he said.

Mr. Navaratna is among a handful of Sinhalese who live in Jaffna, a city situated on a sand spit between two stretches of sea. More than 750,000 Tamils live in the Northern Province, which is drier and harsher than the lushly forested other regions of Sri Lanka.

The Saturday Review is owned by a Tamil, and Mr. Navaratna took over as editor soon after its founding in 1982. Originally, he said in an interview in his high-ceilinged office, he often traveled between here and Colombo, the capital, where his family lives. But he has remained in Jaffna for nearly three weeks, through the spasm of violence that has rocked the area.

“I have been called a traitor by my own people,” he said. “But I am here to build bridges, to bring understanding.”

He added that he was not concerned about any threats to his safety, saying, “The danger will come from the police and the army and not the Tamils.”

He accused the Government of driving the Tamils toward armed extremists, who are known variously as ‘the tigers’ and ‘the boys’, by its policies of racial discrimination and violence.

He added that neither the local commander of the security forces, Brig. Nalin Senaviratne, nor President Jayewardene could control their troops. “I have no hopes of a solution to this problem,” he said. “The more civilians they harass and kill, the more tigers they create.”

What Tamils and their supporters describe as army atrocities have sharpened the ethnic and other differences between Tamils and Sinhalese.

The differences go back nearly 1,000 years to the time when Tamil kings of southern India first invaded the island. The traditional rivalry was fueled when the British brought in thousands of Tamil laborers from India to work their sprawling tea and rubber plantations, work disdained by the Sinhalese.

The Tamils also made good use of the English language to acquire an economic status that far outweighed their numbers. Relations soured further, in the Tamil view, after independence in 1948 as successive governments led by Sinhalese sought to undercut their powerful role.

They made Sinhala the national language and cast English aside. Then Buddhism was made the state religion – most Sinhalese are Buddhists, most Tamils Hindu – and the Government ruled that Tamil students must score higher qualifying marks than Sinhalese to qualify for universities.

During rioting last year, Sinhalese mobs rampaged through Tamil areas of Colombo, burning, beating and killing. Today many of the Tamil shops there have reopened but the fear remains. Most Tamils live in mixed areas of the capital, but thousands are concentrated in one neighbourhood and do not speak Sinhala.”

A Gamini Navaratne item: I provide below a section from Gamini Navaratne’s 1988 article (which I was able to access from Taylor and Francis website journal, Index on Censorship). It was captioned “How we beat the bombs and censors in Jaffna”.

“It was 1 November 1984, the day after the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. There was deep mourning in northern Sri Lanka, homeland of the Tamil minority who had looked to her as their defender in the struggle to obtain legitimate political rights.

I was shopping in the grand bazaar of Jaffna, the northern capital. Suddenly, around noon, an army convoy arrived. About 100 soldiers left their weapons in the armoured cars and trucks and began dancing on the road to the refrain Amma Yenge? (“Where is mother?”).

The majority Sinhalese community normally are not known to celebrate the death of even their worst enemy. I was ashamed at the soldiers’ conduct and remonstrated with them. Tamil militants dragged me back and said: ‘We will handle this.’

They attacked the soldiers with home-made bombs and grenades. The soldiers fled but returned the next day to the identical spot at the same time and sprayed the area with machine-gun fire. Nine people were killed and others injured, among them women and children. I was barely a hundred yards away.

This was one of the many dastardly events in the war between President Junius Jayewardene’s security forces and the militants that I witnessed in four dramatic years in Jaffna as the editor of the Saturday Review.

The Review is the only English newspaper published outside the southern (Sinhalese) capital of Colombo, where the mass media are concentrated, almost all under official control or influence.

The North received little or no attention in the Colombo-based media, so the Review was launched in January 1982. From the start it was fiercely independent.

The government banned the Review in June 1983, using emergency powers. The then editor, S. Sivanayagam, was summoned to Colombo for police interrogation. He feared for his life and fled to Madras by boat.

New Era Publications Ltd petitioned the Supreme Court, claiming the government action grossly violated press freedom. The petition was dismissed and the paper stayed shut for seven months.

When the ban was lifted, the management of Tamil Hindus asked me, a Sinhalese Buddhist from the South, to become editor. I had been the Review’s political and economic correspondent, operating from Colombo where I run a foreign news service.

The Review was allowed to restart on 18 February 1984 under rigid censorship which did not then apply to other publications. Each item for publication had to be submitted to the government administrator of Jafna. Page one of every issue announced that the Review was ‘the only government-controlled newspaper in Sri Lanka.’

I gave the censor headaches by submitting piles of copy, including whole books and magazines. Most were not intended for publication and in any case could not be accommodated in the 12-page tabloid.

The censor did not catch on in the two yeas while censorship applied.

The blue pencil was used liberally, but the Review continued to slip in scoops. At times there was open defiance. I felt the truth had to be told of what was happening in the north, regardless of the consequences.

The Review highlighted security force atrocities against civilians. An exasperated government ordered that all copy be referred to Colombo. It was virtually impossible to run a newspaper in these conditions. Copy got delayed because of frequent transport disruptions. Several times I was hauled before the censor and the Press Council and faced censure, but the Review did not bow down.

At the start I did a weekly run to Jaffna by train – it then took only six hours for the 250-mile journey from Colombo – put the paper to bed and return within two days. Fellow journalists called me ‘the editor who is always o the run’.

Later, as the violence escalated, road and rail transport often failed and I would get stranded for weeks either in Jaffna or Colombo.

The journey by bus was particularly hazardous because of the numerous army and police checkpoints – at one time nearly 20 – and the presence of home guards (armed civilians helping with the checking). Many times passengers were looted, assaulted or even killed, especially by the homeguards.

The Review had been particularly harsh on the Colombo newspapers, which usually relied on official handouts for news about the north. In one issue I said: “Sri Lankans in the south continue to be fed on a diet of lies, more lies and damn lies on events in the northern and eastern provinces (where most Tamils live).

“We should like to warn the Jayewardene government that this exercise could be counter-productive. We should also like to repeat our invitation to journalists from the south to come and see what is happening in a part of Sri Lanka which many Sinhalese claim to be theirs.”

No journalist from the south took me up. Almost every Sinhalese was convinced that Jaffna was ‘enemy territory’ and his life would be in danger there….” [Index on Censorship, 1988, vol.17, issue 4, pp.26-27]

Though this feature by Gamini Navaratne was two pages long, I could access only the first page freely.

A brief quip in the New Internationalist journal

The May 1989 issue of New Internationalist journal (issue 195) carried the following quip under the caption ‘Journalists at risk’.

“In Sri Lanka, journalist Gamini Navaratne was for years virtually the only Sinhalese civilian living and working in the Tamil-dominated north. He both angered the military – by witnessing and reporting on army brutality – and was seized and held by anti-Government rebels. Despite the danger coming from all sides, he has continued chronicling the situation as he sees it.”

S. Sivanayagam’s Eulogy

I provide below what Sivanayagam’s brief eulogy to Gamini.

Remembering Gamini Navaratne

[Hot Spring, London, March 1998, p. 35]

Gamini Navaratne who passed away recently was a journalist who had a long stint in the Colombo newspaper world. Starting life in the sub-editorial staff of the Times of Ceylon, he became chief sub-editor of The Sun and later occupied the same position in the tabloid Ceylon Daily Mirror, all three papers now extinct. But Gamini will be best remembered for his association with the Jaffna-based weekly, the Saturday Review, of which I was the founding editor. He was the paper’s political correspondent in Colombo from the very inception, and later took on the mantle of editorship, during the paper’s second phase of life beginning February 1984. That was when the Jayewardene government lifted the ban on the newspaper, but permitted republication under strict conditions of censorship. I was then safely away from the clutches of the Sri Lankan government, having fled to India in September 1983, following the C.I.D’s ‘invitation’ to me to report at Colombo’s dreaded 4th floor. (How having eluded the long arm of one government, I fell foul of another is of course another story altogether).

The Saturday Review was born in January 1982, motivated by the need for an English publication, to articulate ‘Tamil grievances, following the burning of the Jaffna Public Library, the previous year; a dastardly act that wounded Tamil sentiment deeply. The Jayewardene government did not take to the paper kindly, and it was a case of living from week to week, ever waiting for the axe to fall anytime. It was under such circumstances that Gamini Navaratne, a Sinhalese Buddhist, chose to work for the paper while living in the inimically communal environment in Colombo. Gamini’s association with Jaffna and the Saturday Review could best be expressed in his own words. Writing in a reminiscent vein in a special issue that he brought out (26 January 1985), to commemorate the third birthday of SR, he said:

“When it was proposed to launch the Saturday Review, I told Mr. S. Sivanayagam, its first Editor – my colleague in the Daily Mirror in 1964 and a good friend ever since – that I would give him all the help I could from Colombo. I wrote to him: ‘just because you are there, solely because you are there, I shall do everything possible to keep the Saturday Review going…because I respected him as a journalist, intrepid, innovative, and indefatigable. I added that any time he wanted my physical presence in Jaffna, I would come over and assist. But I did not bargain for a prolonged stay in Jaffna, which has been my predicament.

“I last met Mr. Sivanayagam in Sri Lanka on 1st July 1983. As I took his leave under the temple tree in front of the office, after enjoying his hospitality for a week, I said I feared that the days of the Saturday Review were numbered. There were plenty of persons in the Government who wanted the paper banned; it was becoming a damned nuisance for them. I had just reached my hotel and begun packing my bags when he telephoned to say that my worst fears had been proved correct. By Emergency Regulations, the Saturday Review office had been sealed…”

Looking back, it should make us wonder how a Sinhalese, a Buddhist moreover, came to have the unique distinction of being invited to edit a paper which had already earned notoriety in many Sinhala eyes as a ‘Tiger paper’ and ‘Eelam paper’ within its 1.5 year existence. It was after all the immediate post-1983 period in th island’s history when there was a total breakdown of trust between the Tamil and Sinhala peoples. That was therefore an act that called for, confidence, courage and trust on both sides. To lift himself from his own physical and mental environment that was seething with hostility against the Tamils, compounded by the animosity within the Colombo media world itself in which he functioned, and to accept that position, living as the solitary Sinhala civilian in a militarized zone and without a sense of alienation – that was Gamini’s greatest triumph.

Gamini was a bachelor; a loner in many ways too. To me, it is a matter of personal regret that during the later years, we lost our relationship somewhere down the way.

Gamini Navaratne’s reports to the Times of India daily (1981-1984)

Among the three items I reproduce below, for the first one which appeared soon after the burning of the Jaffna public library in June 1981, I had missed the date of publication inadvertently. I regret this error. From internal references cited, it could be inferred that this report should have appeared after June 10, 1981. Navaratne’s euphemistic reference ‘men in khaki’ refers to the unruly Sri Lankan police force, Sri Lankan army cadres or anti-social elements cloaked in khaki dress. For the next two reports, the published dates are appropriately noted.

Race Riots in Sri Lanka: Government in a dilemma

[Gamini Navaratne, Times of India, June 1981]

Colombo: The changed mood of the Tamils after the recent ‘police violence’ in the northern province is posing serious difficulties for President Jayewardene’s United National Party government in arriving at a negotiated settlement of Sri Lanka’s minority problem.

The Tamils feel humiliated as the Sinhalese have taken the fight to their heartland. Their attacks so far were concentrated on the members of the minority community living in Sinhalese areas outside the Tamil-majority northern province.

A recent statement of Mr. Appapillai Amirthalingam, general secretary of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and leader of the opposition in parliament, reflects the Tamil despair. He said that each time a Sinhalese was harmed in the north ‘we Tamils get the worst of it.’ The reference was to the unprecedented violence unleashed by ‘gangs of khaki’ on innocent Tamils after the killing of a Sinhalese policeman. More than the harm done to persons and property, Tamil pride has been wounded by the mindless vengeance wreaked by the police. The upshot is that greater numbers of Tamils now seem ready to support the separatist demand for ‘Eelam’ which, in effect, means independence for the Tamil majority in the northern and eastern provinces.

Lukewarm

This correspondent had visited Jaffna, 430 km from Colombo, shortly before the development council elections. Most people interviewed then were lukewarm towards the separatist cry raised by the TULF, though they generally supported that party in the absence of a viable alternative. They were more keen to try and get their other main demands conceded by the government by persuasion and live in peace with the Sinhalese. (They have been clamouring for a more equitable sharing of state power and revenue, better educational facilities, more state jobs and more land).

But since the police violence, their mood has perceptibly changed due to both frustration and anger. Almost every Tamil interviewed during my second visit after the tragic episode said he saw no alternative to Eelam (home).

During the elections to the new decentralized administrative units styled ‘development councils’ – the first of their kind – the authorities feared eruption of violence not only in Jaffna but also in the 16 other districts where polling was due on June 4. So the government made massive security arrangements for the occasion. But eventually violence was confined to Jaffna and it occurred on a scale unanticipated by anyone.

A former member of parliament, Mr. A. Thiagarajah, the UNP’s top candidate at Jaffna, was gunned by terrorists on May 24. The incident generated anti-TULF feeling among the public because the terrorists are generally believed to be present or past members of its militant youth wing which is impatient with the slow progress towards Eelam. In government circles in Colombo there was talk of the need to ‘teach the TULF leaders a lesson.’

Then on May 31, four policemen were wounded in a shooting incident at a TULF meeting. One of them, a Sinhalese, died instantly. This was a signal for the ‘men in khaki’ to go on a rampage – assaulting, looting and setting afire public and private institutions, homes and shops the same night. What surprised most people was that the police violence continued the next night – even after the arrival of the defence secretary, Col. C.A. Dharmapala, the army chief of staff, Brig. Tissa Weeratunga, and the police chief, Mr. Ana Seneviratne, and the tightening of security.

The institutions destroyed include the Jaffna public library, one of the finest in Asia, the office of Eelanadu – the leading Tamil daily published in the north, the TULF headquarters and the residence of its youth wing leader, Mr. V. Yogeswaran, who is also the MP for Jaffna.

Reports reaching Colombo spoke mostly of ‘men in khaki’ because the informants were unsure whether the maurading gangs consisted of Sinhalese policemen, troops or outsiders wearing uniforms. Probably all three elements were involved. Indeed, some police units and a number of soldiers were withdrawn from the peninsula immediately. While the authorities blamed the shooting of the policemen on the terrorists, some reports indicated that there was a fight among themselves. Among the policemen hit was a Tamil who died several years later.

Emergency

The declaration of emergency rule on June 2 in Jaffna brought the situation under control. Ten persons were shot by the security forces ‘for breaking curfew’. Quite a number of people, mostly youths were killed by the police and troops during the emergency. Unofficial estimates put the figure at 50. So far, 20 bodies have been found in various part of Jaffna district.

Jaffna, the northern capital, went to the polls as scheduled on June 4, in a tense atmosphere. That morning Mr. Amirthalingam and three other TULF parliamentarians were arrested for allegedly ‘attempting to disrupt the democratic process’, but were released on the President’s order. The police hooliganism and the arrest had created a strong, anti-government feeling and with that whatever chances the UNP had of making a good show at the polls vanished. In government circles, there was a talk of cancelling the election in the disturbed district. But there is no provision for it in law and the election commissioner Mr. A. Piyasekera, directed that the counting be proceeded with and the results announced.

The TULF has been boycotting parliament since June 10 and demanding an ‘international commission’ to investigate the incidents. The government has promised a national commission. Mr. Amirthalingam has rejected the offer on the ground that similar commissions in the past had ‘served little purpose’.

As for the future, the government has three options in theory. First, it can try to resolve the communal problem within a unitary framework by granting the Tamils a bigger share in the administration, especially in the Tamil-predominant northern and eastern provinces. Or, it can go in for ‘federalism’ which was the demand of the Tamil Federal Party until 1973 when it transformed itself into TULF and set Eelam as it goal. Finally, it can opt for Eelam.

Two Options

The Sinhalese are bitterly opposed to both federalism and separation. They fear that the Tamils would eventually link it with their compatriots across the sea in South India topose a threat to their soverignity, as in the ancient past. The two main Sinhalese parties, the UNP and the SLFP, which reflect this attitude, are unwilling even to consider these options.

In any case, Eelam would require large-scale migration of Tamils northwards to Vavuniya and beyond. The large number of Tamils in the rest of the country are reluctant to move because economic opportunities exist mostly in the south. But they may be forced to do so if they are physically attacked, as had indeed happened in 1958, 1961 and 1977. And fresh attacks are possible if either the TULF begins to press hard for separation, as happened in 1958 and 1961 when the Federal Party launched its satyagraha campaigns, or any Sinhalese in the north is harmed as happened this month.

Indeed, the Tamil extremists, aware of the latter possibility, might indulge in more terrorism, hoping thereby to provoke the Sinhalese and make their dream of Eelam a reality. Drawn mostly from the economically weaker sections, they have, have little sympathy for the generally affluent Tamils settled in the south. In fact, economic disparities are at the root of the Tamil separatist demand.

Though President Jayewardene has left the door wide open for negotiations, saying that he ‘does not want Jaffna administered and ruled by the army as in Ulster’, the only way he could win over the TULF is by granting greater regional autonomy than envisaged under the development council scheme. But then he has to contend with the Sinhalese pressure groups. If the Sinhalese remain unyielding it might precipitate just what they feat most – Eelam.

Sri Lankan Law curbs basic freedoms

[Gamini Navaratne, Times of India, April 30, 1982]

Colombo: Opposition parties, jurists and civil rights organisations in Sri Lanka view the amended anti-terrorist legislation as a measure that abridges severely the fundamental rights of the people. Their fear is not without foundation. For the amended law empowers the executive to decide where a person charged under the act be kept in custody.

The new law is the result of a Supreme Court ruling on a habeas corpus application made on behalf of a number of Tamil youths detained in an army camp at Panagoda, near Colombo. Earlier, the lower court of appeal had held that at least two of these detainees had been tortured in army custody.

Mr. Justice Victor Perera, of the Supreme Court, delivering the majority judgement, held that there was specific provision in the anti-terrorist act for the remand of the accused, ‘subject to the specific restrictions’ stipulated therein. Thus, as in the case of other offenders, those charged under this act were to be taken away from the custody of the executive and placed in the custody of the judges in a remand prison or jail to ensure that they received a fair trial.

The government then sought to amend the act to enable the minister of defence to determine the place of detention. When, as the 1978 Constitution requires, the amending bill was sent to the Supreme Court for a ruling on its constitutionality, it held that section 15 a(1), which sought to substitute the remand order made by a court with the minister’s order of custody, ‘constituted an interference with judicial order’ and was ‘inconsistent’ with the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution.

Referendum needed

The bill could become law, the court further held, only if passed by a two-thirds majority in parliament and approved by the people in a referendum.

However, it conceded that ‘there could be no doubt that the minister would be the best judge of what is necessary in the interest of national security and public order in any given circumstance’. And there would be no inconsistency if the executive order for custody is made by the secretary to the ministry of defence as provided in the amending bill, ‘subject to such directives as may be given by the high court to ensure a fair trial of the person/persons in custody’. This advice of the Supreme Court was accepted by the government which thus got around the obligation to seek popular approval through a referendum.

The bill was then rushed through parliament in March during a single day despite protests by opposition MPs.

The minister of justice, Mr. Nissaka Wijeyeratne, presenting the amending bill, emphasized that the amendment was imperative to counterterrorism (by Tamil extremists) in Jaffna (predominantly Tamil-inhabited north Sri Lanka).

The leader of the Tamil United Liberation Front, Mr. M. Sivasithamparam, retorted that his party was opposed to undertrials being kept anywhere else except in remand under judicial custody. How could a fair trial be ensured when the man being tried was sent back to the custody of persons against whom allegations of acts of torture had been made in the court?

Amending Bill

Mr. Sivasithamparam said, that the amending bill would have retrospective effect and could be used against anyone anywhere in the country, not necessarily against terrorists in the north. He noted that among the first to be detained under the act were some trade unionists in Colombo on the allegation that they planned to throw a bomb at President Jayewardene.

Mr. Sivasithamparam reminded the ruling United National Party that when similar provisions were made in the law enacted in 1962 to deal with persons suspected of planning a coup d’etat against Mrs. Bandaranaike’s government, Mr. Jayewardene led the opposition to it. His government was now doing the same thing it had once opposed.

The international commission of jurists, which had condemned the 1962 legislation, also condemned the 1979 act, stating that ‘the only other country in the world which has got similar provision is South Africa’.

Heedless of the opposition criticism, the amending bill was passed by 127 votes to 12.

The fact is that the Sri Lanka constitution has an impressive array of fundamental rights. But these are justiciable only up to a point. For a variety of reasons, including national security and public order, these rights can be legally restricted, as President Jayewardene’s government has done several times since it enacted the new constitution in 1978.

The helplessness of the courts to protect the fundamental rights of the people was vividly brought out for the first time in the case of Mrs. Bandaranaike. Because of the special law under which she had deprived of her rights as a citizen, the Supreme Court was unable to entertain her appeal even though her counsel reminded it that even convicted murderers could not be denied the right of appeal.

Tamil exodus from Lanka

[Gamini Navaratne, Times of India, March 28, 1984]

Colombo: Mounting tension and fears of a repetition of last year’s violence following the government’s decision to impose military rule in Jaffna from April 1 are forcing Tamils from Sri Lanka to flee the country.

It was the killing of 13 Sinhalese soldiers by militant Tamil youths in an ambush at Jaffna during the ‘state of emergency’ declared in the northern area that had provoked the slaughter of Tamils living in Sinhalese-dominated areas in the south in July last year.

Lanka suffers

Already, thousands of Tamils have gone abroad and thousands more are preparing to leave. While most of the Sri Lankan Tamils (those whose families have lived on the island for generations) have gone to the United States, Canada, Britain, West Germany, Australia or the Scandinavian countries, the Indian Tamils (those of more recent Indian origin) have fled to South India.

The exodus has cost Sri Lanka dearly. The majority of Sri Lankan Tamils who have emigrated are leading professionals in the academic, medical and engineering fields. The Indian Tamils who have left were mostly employed in the plantations and their departure has disrupted the tea industry, which is the country’s major foreign exchange earner.

The Tamils’ fear is rooted in the fact that during last year’s riots Sinhalese policemen and soldiers had also taken part in the rioting or had looked on impassively while rampaging mobs attacked Tamils and their property. Even some leading members of President Jayewardene’s United National Party (UNP) government had allegedly instigated the mob. The President had failed to take action against the perpetrators of the violence.

That the Tamils’ fears are not unreasonable is proved by what happened in Colombo about a fortnight ago after rumours spread that two Air Force men had been killed by Tamil extremists in Jaffna. Immediately, shops downed their shutters and schools and offices closed to enable people to return home early because of renewed violence. The government had to take emergency steps to preserve the peace and lost no time in denying the rumours.

The Tamil community has all but given up hope of any solution emerging from the round table conference convened by the President on the ethnic problem. Practically no headway has been made since the talks began on January 10, mainly because of the intransigence of representatives of the majority Sinhalese Buddhist community, among who are members of the ruling UNP.

Since independence in 1948, leaders of the Tamil minority have been demanding a more equitable share of state power. They claimed they had been discriminated against in spheres like higher education, government jobs and land settlements. In fact they were treated like second class citizens. This complaint was acknowledged by the UNP in its 1977 election manifesto, in which promises were made to convene an all-party conference immediately after the poll to work out a settlement. However, President Jayewardene delayed the talks until his hand was forced by the ethnic violence.

Buddhist opposition

Now that the conference is finally being held, the Sinhalese Buddhist representatives have claimed that the majority community has more grievances than the minorities. According to them, in every sphere the Tamils enjoy more than the share warranted by their proportion of the population – 12.6 percent of the 15 million inhabitants of the island. Some of them have suggested that a system of ethnic quotas should be devised for admission to universities, public services and other spheres, on the Malaysian pattern.

The Buddhists have also expressed opposition to the draft settlement worked out between Mr. Jayewardene and leaders of the Tamil United Liberation Front, the main party of the Tamils, in New Delhi thorough the good offices of the Indian Prime Minister’s special emissary, Mr. G. Parthasarathi. This envisages the setting up of regional councils in each of the Sri Lanka’s nine provinces which would be vested with wider powers than the present development councils in 22 administrative districts. In return, the TULF agreed to drop the demand for a separate ‘Eelam state’, comprising the Tamil-dominated northern and eastern provinces, in favour of the linkage of the two provinces to form one regional council. On this note the talks have been adjourned to mid-May.

Consequently, an increasing number of people are coming round to the view of the ‘hawks’ in the TULF that only in a state of their own would Tamils be able to live with self-respect.

Tension is also increasing in Jaffna following the government’s appointment of Mr. Lalith Athulathmudali as minister for national security and the decision to impose military rule in the district from April 1. Brig. Nalinn Seneviratnehas been appointed coordinating officer in charge of security aspects and the civilian administration placed under him. At the same time, the Tamil government agent (administrator) of the district has been replaced by a Sinhalese.

All these are part of the plan to restore law and order in the region and revamp the administration, which has been undermined by the depradations of militant youths who have styled themselves ‘freedom fighters’ and operate under the name ‘Liberation Tigers’.

At present, the administration’s writ does not run far from the government agent’s office and there is no local government to speak of since the withdrawal of the TULF representatives from local bodies last year in protest against the failure to redress the Tamils’ grievances. Units of the armed forces venture out of their barracks only in heavy convoys as if they are in enemy territory.

Observers of the situation in Jaffna believe a ‘military approach’ could be counter-productive as on the previous occasion when it was tried out. In July 1979, Mr. Jayewardene declared a ‘state of emergency’ in the north and sent additional troops there with orders to ‘exterminate terrorism within six months’.

Over a score of suspected youths were killed and there was a lull in violence for some months thereafter, leading the government to believe the problem had been solved. Soon, however, killing of members of the security forces, bank robberies and other terrorist activity increased.

Observers point out that instead of driving a wedge between militant youths and the bulk of the Tamil people, who are not in favour of using violence to achieve a separate Tamil state, the use of force has made the people sympathetic to the militants.

This is because the security forces would round up large numbers of innocent youths on suspicion, when they were not able to apprehend the perpetrators of violence, and on occasions torture or even kill them. This helped to swell the ranks of the ‘Liberation Tigers’.

The government’s case, as put before the world through publications such as ‘Sri Lanka: Beyond Conflict’ (by a former journalist, Mr. Ernest Corea, now Sri Lanka’s ambassador to the USA) is that the present plight of the Tamil is due to the activities of ‘terrorists’. Mr. Corea also asserts that the separatist slogan ‘did not enter Sri Lanka’s political lexicon until 1976’, when the TULF adopted a resolution to this effect.

Refuting this stand, the Tamil Information Centre at Madras issued a booklet titled: ‘Dear Sri Lanka ambassador…your slip is showing’. Incidentally the Tamil Information Centre is headed in Sri Lanka by Mr. S. Sivanayagam, who was editing a Jaffna-based English weekly, ‘Saturday Review’, until it was banned in July.

The booklet says the fact that the separatist slogan was not adopted until 1976 stands to the credit of Tamils. For 20 long years they suffered racial discrimination, racial riots, plunder of their traditional homelands, police and army harassment and open state hostility. In that period, they raised their voice in parliament, from public platforms, through the media and in international forums. They went before the court of law, they staged non—violent protests, they entered into pacts, into gentlemen’s agreements with Sinhalese leaders, which were dishonoured.

‘In short, Tamils over those 20 years were exhausted all peaceful democratic options open to an oppressed minority. They had placed trust in the Sinhalese majority at the very threshold of independence and that trust was betrayed.

‘And after 20 years of absolute and complete disillusionment, an ever-wrosening dimunition of dignity and self-respect, with job opportunities diminishing every year and threats to life and limb adding to their tension and worries, if after all these Tamils thought of settling in their own homeland in arid government-neglected undeveloped north and east, where they traditionally settled for centuries, what are you gripping about Mr. Corea?’

Yes well known editor. He ridiculed the death of Maveeran Thileepan .

knowing that he would not live long and die very soon due to injury in his bowel

Thileepan observed fast.