Father’s Lineage and Work in Ceylon

by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 11, 2018

I wish to express my thanks for the correction note that I received from fellow MGR biographer and friend Mr. R. Kannan, related to previous Part 43 item on M. Karunanidhi’s alleged role in expelling prominent rankers from the DMK party. Kannan had written,

“[Sivaji] Ganesan records in his autobiography that Kalaignar [Karunanidhi] was on his side during the unpleasant 1956 incident [that caused Sivaji Ganesan to leave DMK]. Secondly, Hardgrave whose writings I greatly enjoyed is incorrect about MGR’s waning popularity as well on the allocation of the constituency [for the 1967 election]. The allocation was done by Anna possibly in consultation with MGR.”

“[Sivaji] Ganesan records in his autobiography that Kalaignar [Karunanidhi] was on his side during the unpleasant 1956 incident [that caused Sivaji Ganesan to leave DMK]. Secondly, Hardgrave whose writings I greatly enjoyed is incorrect about MGR’s waning popularity as well on the allocation of the constituency [for the 1967 election]. The allocation was done by Anna possibly in consultation with MGR.”

A hostile blogger’s plagiarism

A hostile blog authored by one Rama Chandran,(identifying himself as a journalist from Kerala state) posted in January 2015 has recently come to my attention. [https://hamletram.blogspot.com/2015/01/mgrs-father-and-caste-inquisition.html]. It is entitled ‘MGR’s father and the Caste Inquisition’. MGR’s father was Melakkath Gopala Menon. Thus, I interrupt the chronological flow of this series, to write about the period 1914-1920, when Gopala Menon’s family lived in colonial Ceylon. When I began this series in December 2012, I didn’t have much data on Gopala Menon; but thanks to help from Mr. Kannan, I was able to tie together the meager bits of known facts with the contemporary events of the 2nd decade of the 20th century, to write this chapter.

What was interesting for me in the hostile blog of MGR’s namesake, Rama Chandran was that it cites 6 sources as ‘Reference’, among which items 2 and 3 cited were that of ‘Nan Mugam Parkum Cinema Kannadikal/ Arurdhas’ and ‘Media Marathon/Erik Barnouw’. This guy had done a neat copy and paste job of cribbing materials that had appeared in Part 1 (Erik Barnouw’s quote) and Part 3 (my English translation of Arurdhas item) of this MGR Remembered series in 2012 and 2013, without due acknowledgment. Furthermore, additional information presented in this blog on MGR’s parents is unreliable and somewhat derogatory. On flimsy evidence, he has presented MGR’s father as a libertine and thus by extension, MGR himself [as “who dabbled with women, on screen and off screen, with his father’s DNA”, in the words of this blogger] also in the same category. However, reliable evidence prove otherwise. Like all of us, MGR was not a perfect human, but portraying him as a Lothario is erroneous and an insult to his mother’s disciplinarian traits.

Though 30 years have passed since MGR had died, still quite a number of actresses live in Chennai and elsewhere whose movie careers were enhanced by their association with MGR and contribution to MGR’s movies. These include 17 senior artistes such as B.S. Saroja, Sowcar Janaki, Vyjayanthimala, M.N. Rajam, T.D. Kusala Kumari, Jamuna, B. Saroja Devi, L. Vijayalakshmi, C.R. Vijayakumari, K.R.Vijaya, Rathna, Rajasree, Kanchana, Vennira Aadai Nirmala, Kumari Sachu, Lakshmi and Latha. Among these, Saroja Devi and Latha were MGR’s two movie muses, as I presented in part 28 of this series. Unlike the contemporary #Me Too Movement in Hollywood and elsewhere, NOT A SINGLE ONE of these movie heroines from South India had complained about MGR ill-treating or harassing them. Why? Partial reason is evident in MGR’s autobiography itself. He was brought up by an illiterate, God-fearing (Goddess Kali worshipping), disciplinarian mother who would slap her teenage son, on hearing the utterance of blasphemy to her face. Such a disciplinarian mother had instilled in her son the merits and virtues of respecting feminism. The recurrent leitmotif in the titles, plots and songs of many MGR movies [including his own production, Adimai Penn (1969, Slave Woman)] was none other than mother worship. Even MGR’s critic cum biographer, Pandian acknowledges MGR’s contribution to ‘women’s liberation’ and respect in his movies to (1) the prominence of sexual desire and freedom for his female audience, and (2) primacy to the role of the mother. Thus, it is nothing but preposterous to portray that MGR was a real life Lothario, based on flimsy evidence of a colonial period trial of Smartha Vicharam (a Caste Inquisition, complete records of which have been lost to time) in which his father Gopala Menon was trapped in the first decade of the 20th century!

In my readings and collection of ‘MGRiana’ for the past 50 years, I had come across only two reports in which MGR had ‘difficulty’ or conflicts with two recognized women. One was with that of P. Bhanumathi, the multi-talented actress singer and his heroine, during the production of his own movie ‘Nadodi Mannan’ (1958). This conflict was simply based on artistic difference of opinion and Bhanumathi was removed in the middle of production. The second criticism relates to his Chief Minister period. It was from Bharata Natyam dancer-actress Kamala Laxman in an interview that she didn’t receive any encouragement for her artistic contribution to dance. One doesn’t know the truth behind Kamala’s complaint. Maybe, she would have perceived that MGR had his favorites among dancers and she was treated badly by the officials who made the decisions in allocating state funds. Apart from these two, I haven’t come across any report that MGR had harassed women intentionally. If there are any, I’d like to be corrected.

As I had indicated previously, MGR’s autobiography itself revolves around his relationship with the four women [his mother Sathyabama and three wives] of his life. The above mentioned blogger had written “Even in the marriage of both MGR and his brother, the Malayali root is visible. MGR married thrice…” Sure, it has to be. MGR’s first two wives Bhargavi (aka Tangamani) and Sathanandavathi (aka Ammu kuddy)) were chosen by his mother. MGR didn’t have any say, in these two selections. This again indicates the respect MGR had for his mother’s choices. It has been mentioned that MGR’s alliance with his co-star V.N. Janaki (who became his third wife) began when they starred together in a 1948 movie. One could infer that, as her two daughter-in-law choices for her son failed to produce children, Sathyabama in her old age had relented her control on MGR’s wishes to have a relationship with Janaki, while his 2nd wife was living. Janaki father Rajagopala Iyer was a Tamil, and her mother Vaikom Narayani Amma was a Malayali. Sathyabama died in 1952.

Marlon Brando’s description of his Mother

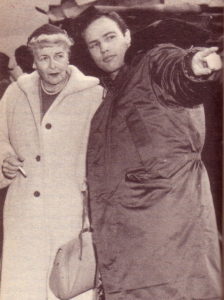

Marlon Brando and his mother Dorothy, few months before she died in 1953

MGR’s illustrious Hollywood contemporary, Marlon Brando (1924 – 2004) lived for 80 years and also wrote his autobiography, in which the subtitle of the book refers to her – ‘Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me’ (1994). Comparing the treatment MGR and Marlon Brando had provided about their respective mothers is revealing indeed. Whereas MGR’s teetotallar mother was an illiterate, God fearing, disciplinarian with compassion to her children, Brando’s mother was an alcoholic, smoker who never cared about her children’s welfare and not at home to discipline young Marlon. Whereas MGR revered his mother for her guidance in his welfare until her death, Brando had contempt for his mother’s dependency on alcohol that ruined his household. Here are two paragraphs by Brando, when he introduced his mother’s alcoholism in page 2 of his book.

“When my mother drank, her breath had a sweetness that I lack the vocabulary to describe. It was a strange marriage, the sweetness of her breath and my hatred of her drinking. She was always sipping surreptitiously from her bottle of Empirin, which she called ‘my change-of-life medicine’. It was usually filled with gin. As I got older, occasionally I would find myself with a woman whose breath had that sweetness that still defies description. I was always sexually aroused by the smell. As much as I hated it, it had an undeniable allure for me.

As her drinking increased, it became more and more difficult for my mother to disguise the fact that she was simply an off-the-shelf drunk. The anguish that her drinking produced was that she preferred getting drunk to caring for us.”

Brando’s description in another chapter, about his interests in women for the sake of sex during his days of early fame in late 1940s on New York stage (around the time, when MGR also gained recognition after his first hero role in Rajakumari movie) is also revealing for the utter lack of influence his mother had in his character development. Brando had reminisced,

“The money that came with A Streetcar Named Desire was less important to me, however, than something else: every night after the performance, there would be seven or eight girls waiting in my dressing room. I looked at them over and chose one for the night. For a twenty-four-year-old who was eager to follow his penis wherever it could go, it was wonderful. It was more than that; to be able to get just about any woman I wanted into bed was intoxicating. I loved parties, danced, played the congas, and I loved to fuck women – any woman, anybody’s wife. Sometimes I did insane things…”

Like Brando, MGR also had good looks for a movie hero and was also rebel of those times. Nevertheless, one cannot imagine, MGR would have behaved like Brando in late 1940s, while he was living in a joint family with his elder brother Chakrapani headed by their mother.

The above mentioned blogger also provides false information that “MGR, in 1956, eloped with V.N. Janaki”. Merde! Either he simply doesn’t know the meaning of ‘elope’ or he hasn’t read MGR’s two volume autography, first serialized in the Ananda Vikadan weekly between 1970 and 1972. This autobiography provides complete details of how his relationship with Janaki was resolved during 1950-1951, with the assistance of his benefactors (director K. Subrahmanyam and his wife S.D. Subbulakshmi and Gemini boss S.S.Vasan) in the Tamil movie world. In 1956, MGR so busy in the Tamil movie world with successive hit movies in production, had his own drama troupe in action as well. Either he should have performed a Houdini act to elope with Janaki in 1956, or he should have fooled the producers of his movies and the drama audience with his ‘double’ standing in for him during shootings and stage.

MGR’s Patrilineal Line

Mr. Kannan had gifted me a one of a kind book in Tamil by Dr. Senniappa Gounder Rasu, who had studied the history of Kongu Nadu Tamils. This Tamil poet had researched MGR’s patrilineal line. This book was published first in 1986, while MGR was alive. The 2nd edition appeared in 2010, with the title MGR Tamilare [MGR is a Tamil]. The following is the synopsis of four generations since mid-18th century, of what Pulavar Rasu had traced.

MGR’s paternal grandfather – Sangunni Valiya Mannadiar (1832-1915)

Due to the East Indian Company’s aggressive policies against the Hindu natives of Konku region of Tamil Nadu during the 18th century, there occurred a movement of Tamils living in the Kongu region to Chera Nadu (now, Kerala state) to protect their Hindu traditions. MGR’s paternal great great grand-father Rama Varma Valiya Raja (1773-1855) who was the chieftain of a‘hamlet’ was one of the affected ones. His wife was Narikodu (aka Ankarathu) Latchumy Amma. The eldest son of this union was Ankarathu Krishna Menon (1800-1855). He was MGR’s paternal great grand-father. The union of Ankarathu Krishna Menon and Simmu Amma resulted in 10 children – 5 boys and 5 girls. The 4th boy was Ankjarathu Sangunni Valiya Mannadiyar (1832-1915), who was MGR’s paternal grand-father. Sangunni Valiya Mannadiyar’s first marriage was to Melakkath Latchumy Amma.

Sangunni Mannadiyar – Latchumy Amma union had two children. The eldest was Melakkath Gopala Menon (1884 – 1920), MGR’s father. The youngest was Melakkath Ravunni Menon. Gopala Menon had three marriages, during his short life span of 36 years. According to information provided by MGR’s elder sibling Chakrapani to author Rasu, Gopala Menon divorced his first wife. To his second wife, there were two male children, eldest was Narayana Menon. Gopala Menon married Vadavanur Sathyabama of Maruthur house for the third time, probably after the death of his second wife. Chakrapani had stated that his two step brothers were brought up by his mother. In a few books published on MGR, an erroneous information that MGR had 4 elder siblings had been repeated without clarification. In his autobiography, MGR mentions only two as his siblings.

MGR’s father – Gopala Menon (1884-1920)

Gopala Menon – Sathyabama union had three children. When this marriage occurred, we don’t know for sure – probably in the latter half of the first decade of the 20th century. We also don’t know the birth year of MGR’s mother Sathyabama. She died in 1952, when MGR was 35. By Hindu tradition, Sathyabama would have been younger to her husband, which sets her birth year as post 1884. Eldest child of Gopala Menon – Sathyabama union was a girl Thangam, who died young around 1921 or 1922, a year following Gopala Menon’s death. This is mentioned by MGR, in his autobiography. Chakrapani was born in 1911 at Vadavanur. The last child Ramachandran was born in 1917, in Ceylon. One could presume that when Gopala Menon took his family to Ceylon, the two children from his second marriage were passed on to relatives for adoption. MGR was conceived in 1916, when Gopala Menon’s family was living in Kandy region.

Conjectures on Gopala Menon’s Work in Ceylon

Kannan had postulated that “The circumstances that prompted the move [to Ceylon] remain unclear. But Chakrapani has said that their father was fond of travel.” My conjecture is that when considering the years Gopala Menon’s family lived in the Kandy environs (circa 1914 to 1920), he might have been hired on a short term 5 year contract for a dual job (teaching cum law-related work) in the estate sector, by the British job contractors in Kerala. I base this conjecture on indirect evidence, after studying the (1) flow of Indian labor from Kerala state to Ceylon during that period, and (2) two vital events that happened between 1914 and 1918. First was the First World War that raged in Europe. Though Ceylon was not directly affected by the war, as it was then a British colony, it can be assumed that some of the administrative decisions made by the British colonial authorities in London and Colombo had a role in the flow of Indian labor into the island. Secondly, the first Sinhala-Muslim ethnic conflict flared in May 1915. The location was Gampola – Kandy region.

A paragraph from the history book of K.M. de Silva (1981) provides a synopsis of this 1915 riots, as follows:

“The riots of 1915 were directed against the Muslims, but more especially at a section of the Muslim community called the Coast Moors who were mainly recent immigrants from the Malabar coast in South India. [Note by Sachi: These were the Mapilla (Moplahs) Muslims of Kerala state.] The ubiquitous activities of the Coast Moors in retail trading brought them in contact with the people at their most indigent levels – they were reputed to be readier than their competitors to extend credit, but they also sold at higher prices. This earned them the hostility alike of the people at large and of their competitors among the Sinhalese traders (mainly low-country Sinhalese), who had no compunctions about exploiting religious and racial sentiments to the detriment of their well-established rivals. Since the low-country Sinhalese traders were an influential group within the Buddhist movement, religious sentiment often gave a sharp ideological focus and a cloak of respectability to sordid commercial rivalry. The Coast Moors were not only tenacious in the protection of their trading interests, but they were also more vociferous than the indigenous Muslim community in the dogged and truculent assertion of their civic rights, which stemmed no doubt from their familiarity with such matters in India. This streak of obduracy and their insensitivity to traditional rites and customs of other religious groups brought them, at a time when there was a resurgence of Buddhism, inexorably into conflict with the Sinhalese Buddhist masses.”

I also located some information on the Kerala migrants to Ceylon in the early decades of the 20th century, from Joseph’s book (1988). Details offered are as follows:

“Migrants from Malabar have been predominantly workers either in the estate or non-estate sectors. The non-estate workers comprised the dock workers, construction workers, miners and factory hands. In this class of labour the Mappilla Muslims of Malabar constituted a very high proportion. Trader migrants consisting mainly of Mapilla Muslims also hailed from Malabar. They engaged themselves as retail distributors, hoteliers, pedlars and panshop keepers….”

Though in one foot note, Joseph mentions that “No accurate data are available regarding the total number of Malayalee migrants to Sri Lanka”, in another foot note he includes the following numbers.

“The total number of Cochinites [Note by Sachi: folks from Cochin princely state of Kerala. This statistic, is 11 years after the departure of Gopala Menon’s family from Kandy.] was 9,618 in Ceylon, as against 3,393 Travancoreans in 1931. The overwhelming majority of the emigrants from Cochin were estate workers in Ceylon. In fact Malayalees in Ceylon were known in general as ‘Cochiyans’.”

In a subsequent foot note, Joseph also includes the fact, “The Planters Association of Ceylon opened 29 agencies for the smooth recruitment and transport of labour from India. One of such agency was in Palghat in the then Malabar district.” The source for this information is ‘Report of Indian Labour emigrating to Ceylon and Malaya (Madras Government Press, 1917).’

By connecting the dots, one can infer that Gopala Menon might have opted to work in Kandy, first as a teacher in estate schools. Then, after the Sinhala – Muslim riots of 1915, he also might have found work as a para-legal official, representing the interests of the Mapilla Muslims of Kerala, in compensation claims – thus, supplementing his primary income as a teacher. Another plausibility is that once the First World War was over in 1918, Gopala Menon’s contract work might have dried up. Thus, he opted to return to Kerala, in 1920. A check of that period’s newspapers in Colombo’s Newspaper repository may provide valuable clues to the institutions in which Gopala Menon was employed.

As one would expect, MGR’s autobiography has only few details about his father, or his paternal lineage. In one chapter, he had passingly mentioned, “My father was blessed with wealth, house and land. Until his death. But, his death happened at the house of his friend, in a different town where he worked; when I was two and a half years old at the house of the grandma of Mr. Peethambaram.” Information provided in Pulavar Rasu’s work, mentions the location as Ottapalam, Kerala state. This Peethambaram later became MGR’s primary make-up man.

Post script: I sent a mail to the blogger Rama Chandran about his plagiarism, on May 8, 2018. As of now, I haven’t heard from him!

Cited Sources

Marlon Brando: Brando – Songs My Mother Taught Me, Century, London, 1994.

K.M. de Silva: A History of Sri Lanka, C. Hurst & Co., London, 1981, p. 382.

Kumbattu Varkey Joseph: Migration and Economic Development of Kerala, Mittal Publications, Delhi, 1988, pp. 42 and 60 (footnote).

Kannan: MGR – A Life, Penguin Random House India Pvt. Ltd, Gurgaon, Haryana, 2017, p. 7.

M.S.S. Pandian: The Image Trap: M.G. Ramachandran in Film and Politics, Sage Publications, New Delhi, 1992.

MGR: Naan Yean Piranthen? Part 2, Kannadhasan Pathippagam, Chennai, 2014, pp. 908-917.

Pulavar S. Rasu: MGR Tamilare, Megathudan Pathippagam, Chennai, 2010. (Originally published in 1986, with the title, Senthamil Veelir MGR).

Thanks Dr. Sachi for the in-depth research into the ethnicity of MGR. Tamils world over have accepted him as their own in spite of misinformation campaign by his opponents, but now that debate is once for all settled by your detailed research. The decorum shown by MGR towards women is legendary and illustrated by all the examples in your article, The allegation by the women named Kamala may be due to her dissatisfaction that she was not appointed as state dancer by MGR.