by T. Sabaratnam, January 22, 2004

Volume 1, Chapter 26

Original index of series

Tamil Votes

Amirthlingam was perplexed when President Jayewardene told him that he would need the Tamil votes to win the

presidential election.

“You have two more years. Why are you talking about the election now?” Amirthalingam queried.

Jayewardene then made his thinking known to him. “I am thinking of advancing the election. I may hold that later this year,” he told Amirthalingam.

He also made a virtue of the foul plan he had hatched. He told Amirthalingam that he had ruled the country for nearly five years and had introduced vast changes. He had opened up the economy, had set up a Free Trade Zone, had accelerated the Mahaweli Development Scheme and had introduced the District Development Councils. He said he wanted to obtain the approval of the people to carry forward these programs.

Then with a puckish smile, he added: If I could strengthen myself, I would be in a position to strengthen DDC scheme.

Amirthalingam told me this in 1984 when he was in Colombo for the All Party Conference and added that he suspected that Jayewardene was playing a fast one on him. He said Jayewardene followed this up with a request. Jayawardene told him that TULF’s support to him should be kept a secret because, if made public, Jayawardene would lose the support of the Buddhists.

Amirthalingam had by then got used to Jayewardene’s “tricks.” He had earlier told me a few of them. Jayawardene tried a classic “trick” during the Inter- Party Talks. Amirthalingam complained to him about the non-implementation of the constitutional provisions concerning the rights of the Tamil language. Jayewardene responded: “The trouble I have is in getting a Sinhala minister to implement the language provisions. They are naturally reluctant because that would affect their political future. If you can loan Soosaithasan (MP from Mannar District) I would appoint him the minister in charge of the implementation of Tamil language provisions.”

Amirthalingam saw the trap. Jayewardene wanted to show the international community that the TULF was with him, put the blame for non-implementation of the language provisions on the TULF and further widen the cleavage between the TULF and the militants. Amirthalingam turned Jayewardene’s request into a joke by saying, “That’s like asking me to loan you my wife.”

This time also Amirthalingam politely rebuffed Jayewardene. He told him that Tamils were disgruntled because of police and army attacks and because the DDC scheme had not been implemented fully. Jayewardene did not let Amirthalingam off easily. He extracted an undertaking that the TULF would not contest the presidential election. Jayawardene told him that if the TULF kept out, Tamils living outside the north and east would vote for Jayawardene.

Jayewardene had told K M de Silva and Howard Wriggins about that conversation and about the TULF undertaking and they have recorded that in “J R Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: A political Biography – Volume Two: From 1956 to his Retirement” (1989), page 531. The section reads:

“J R treated the elections schedule for October 20, 1982, as a logical extension of the campaign of 1977. In planning the new campaign, he sought to move in from a position of overwhelming strength. The UNP was assured of the support of its principal electoral ally, the CWC, as in 1977. When the attempt was made to secure the support of the TULF, Amirthalingam politely rebuffed it, but gave Jayawardene the assurance that his party would not be contesting the election, which, from J. R.’s point of view, was a satisfactory turn of events.”

Jayewardene did not reveal his plan behind the advancement of the presidential election to Amirthalingam. He and his young and brilliant confidants – Gamini Dissanayake and Lalith Athulathmudali- had hatched a plan to retain the enormous power the four-fifths majority in parliament had given him. He had tasted that power the past five years and did not want to relinquish it with the parliamentary election scheduled for mid-1983, the next year. The proportional representation system he had introduced in the 1978 constitution would not permit him to achieve that majority in the next election. So, to retain his absolute control over the parliament he planned to extend the life of the 1977 parliament by another six years. He wanted to do that by obtaining the approval of the people through a referendum. To be able to win in the referendum he wanted to be reelected president for a fresh term of six years.

The absolute control of parliament the four-fifths majority accorded was used by Jayewardene to strengthen his hold on power and to weaken and destroy his opponents. He made use of that majority to become Sri Lanka’s first executive president on 4 February 1978 by amending the 1972 constitution to say that the Prime Minister – the position which he then held – should be deemed to have been elected president. He made use of that majority to enact the Special Presidential Commission Law to oust his main rival, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, from politics and, when the Appeal Court held that the law was flawed, he made use of the same parliamentary majority to take away the jurisdiction the Court had to issue writs against the Special Presidential Commission by amending the constitution and handing that jurisdiction to the Supreme Court. He also amended the Special Presidential Commission Law using that majority to correct the flaw.

Once the Special Presidential Commission found Sirimavo Bandaranaike guilty of abuse of power, he made use of the same four-fifths majority to get the parliament to pass a resolution on 16 October 1980 to impose civic disabilities and debar her from parliament for seven years. The day after she was expelled from parliament he got the parliament to amend the Elections Act and the Presidential Elections Act to prohibit persons expelled from parliament from contesting any election to any office during the period of disqualification. He got the parliament to include in those amended laws provisions prohibiting such persons from addressing election rallies or meetings in support of any candidate contesting any election.

He also got the parliament to enact a provision to disqualify the candidates on whose behalf the expelled person addressed the election meeting. Jayewardene, naturally, did not want to lose that grip on parliament.

The constitution was amended – Third Amendment – to permit the holding of the Presidential Election prior to the

prescribed six years. Article 30 (2) of the 1978 constitution provided that “The President of the Republic shall be elected by the people, and shall hold office for a term of six years.” And, Article 160 lays down that the First President shall “hold office for a period of six years from February 4, 1978.”

The amendment was passed by parliament on 26 August 1982 by a two-thirds majority; 139 voting for and Sarath

Mutetuwegama, the sole Communist Party MP, voting against. The amendment authorized the President to seek a mandate to hold office for a further term by holding an election “at any time after the expiration of four years from the commencement of his first term of office.”

The SLFP, which was then split into Sirimavo faction and Maitripala faction, abstained. The TULF, that had given an undertaking to Jayewardene not to contest the presidential election, assisted him by getting its members to keep away from parliament at the time of voting.

Kumar Ponnambalam 1982

Nominations for the presidential election were received on 17 September and six candidates contested it. They were: Dr Colvin R de Silva, Lanka Sama Samaja Party; J R Jayewardene, United National Party; H S R Kobbekaduwa, Sri Lanka Freedom Party; Vasudeva Nanayakara, Nava Sama Samaja Party; Kumar Ponnambalam, All Ceylon Tamil Congress and Rohana Wijeweera, Janata Vimukthi Perumuna.

The TULF decision not to contest the presidential election was severely criticized by Kumar Ponnambalam, the militant groups and the TELF.

Kumar exposed the deal Amirthalingam had struck with Jayewardene. TELF, through a leaflet, placed two valid points to substantiate its charge of betrayal by the TULF. Firstly, it argued that the TULF could have reaffirmed the mandate it obtained in the 1977 election for the establishment of Tamil Eelam. Secondly, by not contesting, the TULF lost an opportunity to obtain the support of the Tamils living outside the Northern and Eastern provinces for the demand for Tamil Eelam.

Amirthalingam was stung by these criticisms. But he could not do anything. He got out of the fix by calling on the Tamils to boycott the election. His statement gave the lame excuse that since the Tamils had not accepted the 1978 constitution they should boycott the presidential election called under that constitution.

Kumar Ponnambalam hit very hard at Amirthalingam in his vigorous election campaign. He accused Amirthalingam of going against the mandate he had been given in the 1977 general election. “He is not only trying to defeat me. He is also trying to defeat the demand for a separate state,” he said. In his radio speech, he appealed to the Tamil people to seize the opportunity and show the world their unity, strength and aspirations.

In an assessment of the situation the Saturday Review commented on 2 October that Kumar Ponnambalam, who had “pinched Eelam clothes once worn by the TULF,” was playing the “role of the crown prince to the increasingly appreciative TULF audience.” It added that the traditional supporters of the TULF among the extensive farming villages in Jaffna were supportive of Kobbekaduwa, who promised better prices for Jaffna’s agricultural produce: onions and chillies.

Kobbekaduwa was mobbed by the farming community when he toured Vavuniya, Kilinochchi and the Jaffna Peninsula, where he addressed 14 meetings. He promised Jaffna farmers protected markets for their produce and assured them that the Prevention of Terrorism Act enacted by Jayewardene would be revoked.

Jayewardene’s one-day campaign tour of Jaffna provoked a public protest at the instance of the TELF and the General Union of Eelam Students (GUES). Shops, schools and public and private establishments were closed. Walls were plastered with posters saying, “Eelam people are very hospitable, but not to foreign invaders.”

Jayewardene made use of the rally at Chunnakam to draw the TULF out of the mess it had got into by its boycott call. He said, “I want you to take part in the election. Vote for anybody you like. That is your business, but vote, because that is the sovereignty of the people.”

At Padiruppu, he said, “You have been asked by some not to vote; but I say to you, go and vote for the elephant [the

UNP’s election symbol] for the sake of development, peace and prosperity.”

Though there were charges of violence and breach of election laws, which included sealing of the press and confiscation of the printed copies of Communist Party daily Aththa, the presses where the SLFP printed its propaganda material, Jayewardene won an impressive victory in the election held on 20 October. Polling was high. Over 6.5 million of the 8.1 million registered voters -81.06 percent- cast their votes. The result was:

Though there were charges of violence and breach of election laws, which included sealing of the press and confiscation of the printed copies of Communist Party daily Aththa, the presses where the SLFP printed its propaganda material, Jayewardene won an impressive victory in the election held on 20 October. Polling was high. Over 6.5 million of the 8.1 million registered voters -81.06 percent- cast their votes. The result was:

1. J R Jayewardene (UNP) – 3,450,811, (52.91 percent.)

2. H S R B. Kobbekaduwa (SLFP) – 2,548,438, (39.07 percent.)

3. Rohana Wijeweera (JVP) – 273, 439, (4.19 percent.)

4. Kumar Ponnambalam (ACTC) – 173,934, (2.67 percent.)

Dr Colvin R de Silva (LSSP) – 57,532, (0.88 percent.)

6. Vasudeva Nanyakara (NLSSP) – 17,005, (0.26 percent.)

Jayewardene won with a majority of 902,373 votes, and all candidates except Kobbekaduwa forfeited their deposits.

Jayewardene won in eighteen of the 22 electoral districts- 17 Sinhala districts and the Muslim majority Ampara. KumarPonnambalam won in the Jaffna district.

Kumar Ponnambalam polled 87,263 votes in the Jaffna district, while Kobbekaduwa received 77,300 votes and Jayewardene 44,780 votes, indicating that nearly half of the 533,478 registered voters- 228,613 voters- had rejected the TULF’s boycott call. This led Amirthalingam to realize the danger the TULF was facing. And encouraged by the support Kumar Ponnambalam’s call for the separate state of Tamil Eelam evoked among the voters, EROS and PLOTE decided to jointly contest the general election scheduled for mid- 1983 as an independent group. This, Amirthalingam realized, posed the TULF an additional challenge.

Yet Amirthalingam was unable to wrest himself from Jayewardene’s claws. This was not because he loved his position and perks, but because he feared Jayewardene more. He understood the danger of annoying or irritating Jayewardene. He told me several times, “He is a dangerous man. We must deal very carefully with him.”

Amirthalingam expressed his fear very clearly in June 1982 when he met the members of the Tamil Coordinating

Committee (TCC) headed by Krishna Vaikunthavasan and again on 5 July 1982 at the World Tamil Eelam Conference held in Nanuet, a suburban town of New York, United States.

In London Amirthalingam told TCC members that the Tamil community in Sri Lanka, including those living in the north and east, would be collectively punished if they proceeded to implement the TCC’s decisions: a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 14 January 1982, the Thai Pongal Day and proclamation of a government of Tamil Eelam in Exile.

He repeated that warning at Nanuet.

He told the 200 delegates assembled at the World Tamil Eelam Conference that he was responsible for the lives and the well-being of the Tamils living in Sri Lanka. He asked, “What good liberation would bring if there are no people to enjoy that liberation. Bangladesh liberation, cited by many as example, was the result of the death of three million people, the total number of Tamils living in Sri Lanka.”

Vaikunthavasan, one of the prime movers of the UDI shouted, “Tell Jayewardene to his face, go to hell.”

Amirthalingam retorted, “If I do, it is not Jayewardene who will go to hell. It will be the Tamil people who will end up there.”

Jayewardene and his government started whipping up the feelings of the Sinhala people following the announcement by the Tamil Coordinating Committee of its UDI and Government in Exile decisions. The government extended the state of emergency and announced its plan for a massive crackdown on “any form of violent activism that may be launched by Tigers in Sri Lanka, to coincide with this new London offensive.” The Tamils living in southern Sri Lanka knew the significance of that statement and felt the danger facing them. Amirthalingam was swarmed by all sections of Colombo Tamils urging him to put an end to the UDI madness.

The strong statement the TULF issued dissociating itself from Vaikunthavasan’s folly cooled Sinhala temper. The joint statement issued by Sivasithamparam and Amirthalingam said: “No one can arrogate to himself the right to take any action fraught with serious consequences to the Tamil people in Ceylon.” Its concluding sentence read: “We are fully convinced that this is ill-advised and will not advance the Tamil cause one wee bit.”

The Sun, then the voice of Sinhala chauvinism, and its Sinhala sister paper, Dawasa welcomed the TULF’s statement on 21 December 1981 and helped the Tamils escape getting another punishment. (Note – A detailed account of the UDI decisions is available in K. T. Rajasingham’s Sri Lanka: Untold Story Chapter 28 available through the Sangam website or at http://www.atimes.com/ind-pak/DB23Df04.html)

Kuttimani Episode

Soon after the presidential election, Amirthalingam took a dramatic step to repair the damage his boycott decision and his closeness to Jayewardene had done to his popularity. He made use of the death of T. Thirunavukarasu, the TULF MP for Vaddukoddai, who died on 1 August 1982, to do his repair work. Thirteen days after Thirunavukarasu’s death, the Colombo High Court sentenced to death Kuttimani and Jegan, who had been arrested at Manalkadu on 5 April 1980, after a prolonged and tortuous trial. This was the first death sentence under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. Kuttimani was convicted for the murder of the police constable Sivanesan in 1979 at Valvetithurai. He appealed against the conviction.

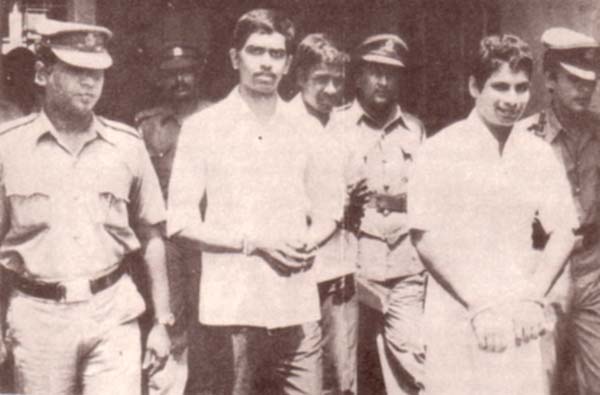

L to R: Jeganathan and Kuttimuni being taken to Court, courtesy TamilNation.org

The TULF nominated Kuttimani to fill the vacancy created by the death of Thirunavukarasu. The 1978 constitution provided for the secretary of the concerned party to nominate another person to fill the vacancy created by the death, resignation or removal of a member of that party. The Elections Commissioner accepted the nomination and notified parliament.

There was uproar in the country and the Sinhala press launched a campaign against Kuttimani’s nomination. A section of the Tamils too criticized the TULF’s nomination. Amirthalingam defended their decision saying, “Kuttimani was chosen to focus the attention of the people on the question of trying Tamil youths under the Prevention of Terrorism law, which admits confession obtained by the police under duress, as evidence.”

Kuttimani accepted the nomination and filed an application with the Appeal Court praying that the court direct the

Commissioner of Prisons to take him to parliament to enable him to take his oath as an MP. The Solicitor General, who appeared for the Commissioner of Prisons, raised a preliminary objection and submitted that the court had no jurisdiction to issue such an order. The Appeal Court upheld the objection.

The court’s order blocked Kuttimani from taking his oath of allegiance to the constitution as required within three months from the date of election, or nomination. He resigned his seat on 24 January 1983, a day before the end of the three-month period. Then the TULF nominated Dr Neelan Thiruchelvam to fill the vacancy and he took his oaths on 8 March.

The Referendum

President Jayewardene created another problem for the TULF while it was struggling with the Kuttimani nomination issue by his decision to hold a referendum instead of the parliamentary election due in mid-1983. Jayewardene, who delayed taking his oath of office as the Second President till 4 February thus extending his period in office by three and a half months, decided to continue his hold over the parliament with its four-fifths majority for the entirety of his second term of presidency.

Jayewardene had dropped a hint about his plan in his speech at Anuradhapura during the presidential election campaign.

He said he was going “to roll up the electoral map of Sri Lanka for ten years.” No one ever guessed that he was going to do that through a referendum to extend the life of the current parliament by another six years.

He started implementing his plan three days after he was declared elected president for the second term. As usual

Jayewardene made use of one of his ministers or trusted men to do his work. This time he got Prime Minister Premadasa to propose that all the UNP MPs should present undated letters of resignation to the president and that, in the interest of on-going national development programs, the life of the present parliament should be extended for a period of six years by obtaining the approval of the people through a referendum.

The proposals were approved by the UNP working committee that evening.

The parliamentary group unanimously endorsed Premadasa’s proposals to sign undated letters of resignation addressed to President Jayewardene and to extend the term of the parliament for a further period of six years from August 1983.

Jayewardene told the parliamentary group that the letters would be acted upon on a later date, if and when necessary.

Those letters securely locked up in his drawer gave him absolute control over the UNP members of parliament who

constituted four-fifths of the total membership.

Jayewardene then moved on to prepare the people to accept his scheme. The state-controlled print and electronic media – Lake House, SLBC, Rupavahini and ITN – were placed in full gear for that purpose. On 2 November they were told to give the maximum publicity to the communiqué that would be issued the next day. And on 3 November a shocking government communiqué was issued. The communiqué signed by President Jayewardene read:

I had information on 21 October 1982 (the day after the presidential election) that a group of the SLFP, which led the presidential election campaign and were in the majority in the executive committee, had decided to assassinate me and a few other ministers, Mr. Anura Bandaranaike, the chiefs of the armed services and officers; and to imprison Mrs. Bandaranaike. In other words, on the strength of their victory establish a military government, tearing up all constitutional procedures, as they announced at their election meetings.

I have to decide whether to allow this to happen or to ask the people whether in addition to my being allowed to govern our country with democratic parliament ensuring peace and progress through a stable government or to permit a set of political hooligans to enter parliament in large numbers and while wrecking democratic procedures to strengthen themselves to form their Naxalite government at the next general election.

I also thought that the democratic members of the SLFP should be given time to assert their authority and gain control of their party.

If I dissolved parliament and held the general election, according to the 20 October voting my party, the UNP, would have obtained 120 seats out of the 196 seats. The SLFP would have obtained 68 seats. I don’t mind that. But I do mind if the opposition is an anti-democratic, violent and Naxalite opposition. The SLFP leadership on October 29 was that. I decided to change my mind and call for a referendum and not a general election for this reason and for this reason alone.

The Daily News in which I worked at that time and other Lake House morning papers- Dinamia (Sinhala) and Thinaharan (Tamil) highlighted the Naxalite plot and buried the referendum plan below. The Daily News headlined: Naxalite plot to assassinate President Bared.

Hector Kobbekaduwa 1982

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) was called in to investigate the Naxalite plot. Some persons including Vijaya Kumaratunga, the popular film actor husband of Chandrika Kumaratunga, who headed Kobbekaduwa’s election campaign was arrested. Kobbekaduwa was also questioned.

The joke those days in the Colombo rumour mill was: There was an old fox who hatched a plot which said his political opponents were planning to assassinate him and his henchmen. To give credibility to his plot, he adds the name of the opposition crown clown. Then, says the Grand Old Lady who led the opposition was to be arrested. The fox called his investigators and they questioned and questioned till the referendum the old fox called to perpetuate his hold on power was over.

The joke apart, Vijaya and some others who opposed the referendum were arrested and locked up. SLFP headquarters were searched and the list of its district and electoral organizers obtained. They were questioned about the assassination plot and, after the polling day, the CID dropped its investigation.

In an interview to Roshan Peiris of the Sunday Times in 1995, long after his retirement, Jayewardene said Vijaya was imprisoned by his government because “the process of law has to be the same for all.” He added, “I rarely, if ever, talk about the fact that Madam Bandaranaike took my son into custody and jailed him.” His son, Ravi Jayewardene, was arrested during the 1971 JVP insurgency.

Jayewardene talks about his son’s arrest occasionally. He talked about it when the late Kosgoda Dharmawansa, head of the Amarapura Nikaya, leading a delegation of Buddhist monks met him and pleaded with him to relent and restore Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s civic rights. He told the monks that it was Sirimavo Bandaranaike who took his only son into custody during the 1971 insurgency and gave him his meals on a tin plate. When the Chief monk asked him whether it was, then, an act of revenge to take away her rights, Jayewardene did not reply. He declined to grant the request the monks asked for.

Vijaya’s arrest was also part of his revenge.

The bill, the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution- for the conduct of the referendum was gazetted on 2 November and Felix R. Dias Bandaranaike and C. V. Vivekanandan challenged its constitutionality before the Supreme Court. The Attorney General informed the court the government intended passing the bill with a two-thirds majority and a referendum. The 7- member bench of the Supreme Court held in a 4-3 decision that it had no jurisdiction in respect to a bill passed with a two-thirds majority and a referendum.

V. N. Navaratnam

The TULF parliamentary group decided on 4 November 1982 to oppose the referendum bill. Chavakachcheri member V. N. Navaratnam led the group that took a defiant position. Navaratnam told the meeting that he would resign his seat at the end of the six-year term for which he was elected by his voters. “Continuing to cling to the seat amounts to outright deception,” he told me. Some members of that group wanted the TULF to join the opposition campaign against referendum. But Amirthalingam had struck an agreement with Jayewardene whereby the TULF would continue the policy it had adopted during the presidential election. The TULF parliamentary group struck a compromise: it would oppose the referendum but would not join the opposition campaign. It also decided that its members should resign at the end of the term of the First Parliament which terminated in August 1983. As a show of their sincerity, all the TULF MPs handed over their letters of resignation to Amirthalingam, As agreed, President Jayewardene announced that he had received assurance from the TULF leadership that it would not actively canvas against the referendum. The TULF kept its undertaking. This helped Jayewardene to retain the Tamil votes outside the north and east.

Amirthalingam participated in the debate and announced the TULF’s opposition when the bill was debated in parliament. He argued that it was immoral for MPs who were elected for a term of six years to be in office for 12 years. He announced the parliamentary group decision that its members would resign at the end of their term. But at voting time, he and other TULF MPs were absent.

The Fourth Amendment was introduced to parliament by Premadasa. Article 2( c ) of the amendment provided: “unless sooner dissolved, the First Parliament shall continue until August 4, 1989, and no longer, and shall thereupon stand dissolved, and the provisions of Article 70 (5) (b) shall, mutatis mutandis, apply.” The Bill was passed by a two-thirds majority on 5 November 1982, with 142 votes in favor and four against. Lakshman Jayakody, Anura Bandaranaike and Ananda Disanayake of the SLFP and Sarath Mutetuwegama of the Communist Party voted against the Bill.

The voting on the referendum was fixed for 22 December and the question placed before the voters was: “Do you approve the Bill entitled the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution published in Gazette Extraordinary No 218/23 of November 13, 1982, which provides inter alia that unless sooner dissolved the First parliament shall continue until August 4, 1989, and no longer and shall thereupon stand dissolved.”

The voters were told that those who approved the bill should mark their vote against the cage which said ‘Yes’ and those who disapprove against the cage which said ‘No.’ To help the voters Yes was assigned the symbol of a Lamp and No the Pot.

Jayewardene campaigned for the Lamp and the opposition led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike for the Pot.

Jayewardene opened his campaign in November third week with a meeting at Kochchikade, Colombo where he said the idea of a referendum was not a new one and was included in the 1978 constitution. He said he was seeking the people’s consent to extend the life of parliament, unlike Srimavo Bandaranaike, who extended the life of the parliament by two years, 1975-1977, without the consent of the people. He added that he wanted the life of the parliament extended to enable him to push through with the government’s development program.

Srimavo Bandaranaike headed the joint opposition campaign as her participation in the campaign would not result in the disqualification of any candidate. In her television address she said, “If you want to preserve your civic rights, I appeal you to vote for the ‘Pot.’ I appeal to you in the name of the future generations to vote for the ‘Pot’ and preserve the franchise that we have safeguarded from 1931.”

She continued in her broadcast, “Casting your vote for the ‘Pot’ does not mean a vote for any party. It is not a vote against any party. The vote for the ‘Pot’ means a vote to retain the right of electing members of parliament and governments enjoyed by you since 1931.”

A rumour designed to win over TULF supporters was circulated in the Colombo grapevine a few days before the voting day.

It said President Jayewardene was actively examining the possibility of appointing Amirthalingam to a very high position in the government so that he would be able to contribute to the solution of the ethnic problem. I asked Amirthalingam about it. “Rubbish!” was his reply but he was not in a position to deny it. He said: “How can I deny a rumour?”

A total of 5,768,662 voters polled at the referendum throughout the country, 70.82 percent against the total number of registered voters of 8,145,015. A total of 3,141,223 voters, 54.45 percent, voted Yes and 2,605,983 voters, 45.17 percent voted No. There were 21,456 rejected votes, 0.37 percent. Despite the thuggery, violence, harassment of the opposition and the extensive violation of election laws Jayewardene was able to win by a majority of only 535,240 votes.

Countrywide, poling in the referendum was over 10 percent less than in the presidential election. In the Jaffna district, however, the voter turnout was higher than in the presidential election. At the referendum 290,849 voters cast their votes as against 228,6 13 voters in the presidential election. Of them, 265,534 voted No, while only 25,315 voted in favor of the extension of parliament. That meant about 19,000 of the 44,780 who voted for Jayewardene at the presidential election had turned against his decision to extend the life of parliament.

Similarly, in three of the remaining four electoral districts in the north and eastern provinces, a majority of the voters voted No to Jayewardene’s plan to extend the life of parliament. In the Vanni electoral district 48,968 voted No and only 25,986 voted Yes. In Trincomalee 51,909 voted No and 39,429 voted Yes. In Batticoloa 72,971 voted No and 47,482 voted Yes. In Ampara 91,129 voted Yes and 62,836 voted No. The refusal of the Tamil people in the north and east to support his scheme naturally annoyed the vindictive Jayewardene. Naturally, he felt they needed to be taught a lesson.

Next: Chapter 28. RAW Meets Pirapaharan

To be posted January 28

###

Volume One

Chapter 1: Why didn’t he hit back?

Chapter 2: Going in for a Revolver

Chapter 3: The Unexpected Explosion

Chapter 4: The Tamil Mood Toughens

Chapter 5: Tamil Youths Turn Assertive

Chapter 6: Birth of Tamil New Tigers

Chapter 8: First Military Operation

Chapter 9: TNT Matures into the LTTE

Chapter 10: The Mandate Affirmed

Chapter 11: The Mandate Ratified

Chapter 12: Moderates Ignore Mandate

Chapter 13: Militants Come to the Fore

Chapter 14: The LTTE Comes into the Open

Chapter 15: The Ban, J.R.’s Gift

Chapter 16: Wresting Weapons from the Enemy

Chapter 17: Sinhala-Tamil Tension Mounts

Chapter 18: Tamils Lose Faith in Commissions

Chapter 19: Balasingam Enters the Scene

Chapter 20: Jaffna Turned Torture Chamber

Chapter 21: The Split of the LTTE

Chapter 22: The Burning of the Jaffna Library

Chapter 23: Who Gave the Order?

Chapter 24: Tamils Still Back Moderates

Chapter 25: Parliament Discuses Ways to Kill Amir

Chapter 26: The First Attack on the Army

Chapter 27: Amirthalingam Taken for a Ride

Chapter 28: RAW Meets Pirapaharan

Chapter 29: The Indian Interest

Chapter 30: LTTE Guerrillas in Action

Chapter 31: The Death of the First Hero

Chapter 32: The Return of Pirapaharan

Chapter 33: Knocking Out the Base

Chapter 34: Tamils Follow Militant Leadership