by T. Sabaratnam, April 8, 2005

Chapter 41

Original index to series

Original Chapter 42 [renumbered from Chapter 40]

In mid- September 1985, the ENLF told the media in Chennai that Sri Lanka had launched a military onslaught code-named Operation Green Arrow in the Trincomalee district in total violation of the ceasefire then in operation. The ENLF told RAW officials, who were pressurizing the the coalition to extend the 3-month ceasefire which would lapse on 18 September, that Jayewardene was trying to deceive all.

The ENLF accused the government of implementing a plan to clear the Trincomalee district of the Tamils. It said Tamil villages were being evacuated and that it reserved the right to “take appropriate action to protect the Tamil people.”

The ENLF accused the government of implementing a plan to clear the Trincomalee district of the Tamils. It said Tamil villages were being evacuated and that it reserved the right to “take appropriate action to protect the Tamil people.”

National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali, who personally supervised the operation from the Navy Camp in Trincomalee, told the media the areas “infested by terrorists are being cleared.” In another statement, he spoke of “flushing out the terrorists.”

Athulathmudali said the areas around Trincomalee and the northern parts of the North Central Province, which included dozens of traditional Tamil villages, were also being cleared of Tamil “terrorist infiltrators,” the ruse he used to drive away Tamil villagers.

Establishing armed Sinhala settlements along the border of the Northern Province was the new twist the Jayewardene government gave to the old policy of state-aided Sinhala colonization of the Tamil homeland which has been implemented by all Sinhala governments since the 1940s. The objective continued to be the same: the weakening and marginalization of the Tamils in Sri Lanka.

Home Guards near Padawiya, 1999

At the start, in the 1940s and thereafter, the strategy was to settle landless Sinhala farmers in the irrigable fertile land in the Eastern Province and the southern border of the Northern Province. This process of land grabbing commenced on a major scale with the Gal Oya project in the then Batticaloa district, the Allai and Kanthalai schemes in the Trincomalee district and the Padaviya scheme in the Vavuniya district. The land grab was gradually expanded, as the years rolled on, despite the protests of the Tamil people. (see Introduction to Volume 1 and Chapter 22 of Volume 2 for a detailed account.)

Jayewardene, who came to power with the support of the Tamils promising them that he would end the Sinhala colonization of Tamil majority areas, began his period of power by unleashing a series of attacks on the Tamil people. The first communal assault by his government was in August 1977, which displaced hundreds of families of plantation Tamils who lived in the midst of the Sinhala people. Some of them migrated to the NorthEast, where they had relatives or friends, seeking safety and security. Some sympathetic Tamil professionals, social workers and Tamil government servants helped them to settle down in border areas in Vavuniya and Batticaloa. They settled the plantation refugees in the border areas to prevent the expansion of Sinhala settlements into the heart of the Tamil homeland. This process went on until 1982.

Jayewardene, who came to power with the support of the Tamils promising them that he would end the Sinhala colonization of Tamil majority areas, began his period of power by unleashing a series of attacks on the Tamil people. The first communal assault by his government was in August 1977, which displaced hundreds of families of plantation Tamils who lived in the midst of the Sinhala people. Some of them migrated to the NorthEast, where they had relatives or friends, seeking safety and security. Some sympathetic Tamil professionals, social workers and Tamil government servants helped them to settle down in border areas in Vavuniya and Batticaloa. They settled the plantation refugees in the border areas to prevent the expansion of Sinhala settlements into the heart of the Tamil homeland. This process went on until 1982.

By 1982, Tamil militancy had grown. Sporadic attacks on the army had escalated. The demand for the creation of a separate state of Tamil Eelam had strengthened. By the end of November that year, police and the army reported to Jayewardene that Tamil militant activity had increased in the Vavuniya district. They complained to him that “terrorist activity is noticed in the settlements of plantation Tamils started by the Gandhiyam Movement.” They recommended that plantation Tamil settlers be evicted to destroy the hideouts of Tamil militants and to allow the overcrowded Sinhala settlements to expand northwards.

President Jayewardene, the Minister of Defence and Plantation Industry, and Gamini Dissanayake, Minister of Mahaweli and Lands, in their inimitable style, prepared the ground through systematic propaganda to flush out the plantation Tamils from the northeast.

Media Strategy

Here I wish to depart from the main story to point out the media strategy adopted by President Jayewardene and his confidants Gamini Dissanayake and Lalith Athulathmudali. They used the Sun and the Island and their sister Sinhala dailies to prepare the people for any drastic action they wanted to take. I once asked Lalith Athulathmudali about their making use of the opposition newspapers for this purpose. His reply was: the Daily News is our paper. When the Daily News or Dinamina carry this type of stories people will know that we gave them. So we make use of the Sun and the Island.”

During this period they made use of Peter Balasuriya of the Island and its weekly Sunday Island and Jennifer Henricus, Ranil Weerasinghe and Anura Kulatunga, of the Sun and its weekly Weekend, all highly respected journalists, for this purpose.

On 28 November 1982, a Sunday, Sunday Island, Weekend and their sister Sinhala papers, led with similar stories charging the Gandhiyam Movement of establishing border villages using ‘stateless persons’ and using them as ‘terrorist training grounds and hideouts.’ They also said ‘Tamil terrorists were building a ‘human fence.’

The story prepared the ground for the police and the army to conduct cordon and search operations and to carry out ‘forced evictions.’ Combined army-police operations became the order of the day by March 1983. The method used was: the Army cordons off the farms where the plantation Tamils live. The police march them to the road, force them into buses and drop them on the streets in the hill country.

On 14 March 1983, the operation was given an added dimension. Police burnt 16 huts belonging to the plantation Tamils at Pankulam, 25 km west of Trincomalee. I was with Thondaman when the news reached him. He fumed. He knew that the police was acting on the orders of Jayewardene. But he was helpless. All he could do was to issue a press statement, which he did.

In April 1983, the Gandhiyam office in Vavuniya was sealed and its founders, Dr. Rajasundaram and S.A. David were arrested under the PTA and remanded in the Welikada Prison. Dr. Rajasundaram was killed in the prison on 25 July. David escaped. He had been transferred to the Batticaloa jail and escaped from there during the Batticaloa jailbreak. He went to Tamil Nadu with other escapees.

Welikada Prison, 2002

By the beginning of July 1983, the harassment of plantation Tamil settlers intensified. Most of them had been evicted. The conditions for mass settlement of Sinhala peasants had been created, but the July anti-Tamil pogrom intervened.

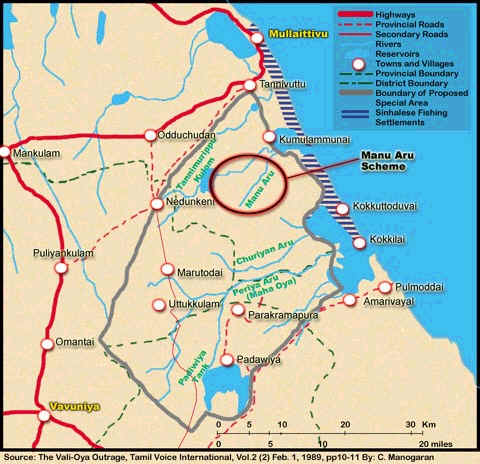

A more vicious plan to destroy the claim for a separate state of Tamil Eelam was hatched during March 1983 at the Mahaweli Ministry. The plan was to knock off the bottom of the Tamil Eelam claim by splitting the Tamil homeland into three pieces through the establishment of Sinhala settlements. The settlements planned were: Maduru Oya settlement, the Weli Oya settlement and the Malwattu Oya settlement. Oya is the Sinhala word for river. The plan was to settle Sinhala farm families in the three river basins.

The Maduru Oya is the boundary between the Tamil majority Batticaloa and Trincomalee districts. A Sinhala settlement in the Maduru Oya river basin would break the land link between Batticaloa and Trincomalee. Weli Oya lies between Trincomalee and Mullaitivu districts. A Sinhala settlement there would sever the land link between those districts. The Malwattu Oya runs south of Mannar. A Sinhala settlement there would rip off the Southern part of Mannar from the Northern Province. When these settlements were completed the Tamils would be left with a truncated Northern Province comprising the whole of Jaffna and Kilinochchi districts and the northern portions of the Mannar, Vavuniya and Mullaitivu districts.

Weli Oya irrigation canal

The Maduru Oya settlement plan was put into operation soon after the 1983 July holocaust. It was abandoned later because Mahaweli Ministry officials messed it up. They were completely open about their justification for the project, resulting in Indian protest and adverse international publicity. An embarrassed Jayewardene was compelled to distance himself from the settlements. However, the plan to implement the Weli Oya project was intensified.

The Weli Oya scheme was revived after the 90-minute visit of US Defence Secretary Casper Weinberger who had tea with Jayewardene in 1983. Weinberger stopped over in Colombo – he called it a refueling halt – on his way from Beijing to Islamabad on 30 September 1983. According to Indian intelligence reports, military assistance to Sri Lanka was the main topic of discussion. Weinberger, those reports said, explained to Jayewardene the difficulty his government faced in providing direct assistance to Sri Lanka. He told Jayewardene that assistance could be arranged through Israel and Pakistan.

In return, Weinberger wrested three concessions: re-establishment of a diplomatic link with Israel; the signing of the Voice of America Agreement; and lease of the Trincomalee oil tanks to an American company. Weinberger told Jayewardene that President Reagan’s troubleshoote, Vernon Walters, would be sent to negotiate those matters.

Weinberger told the media a different story. He said the US viewed the ethnic conflict as a political dispute which require a political solution. He said he had advised President Jayewardene to make use of Indian good offices to work out a political solution.

Asoka de Silva

Emboldened by the US assurance, Jayewardene leapt into action. He directed the Defence Ministry the next week, first week of October 1983, to form a new organization called the Joint Services Special Operation Command (JSSOP). It brought together the three armed services and the police under one command structure. Navy Commander Asoka de Silva was appointed Coordinator and D. J. Bandaragoda, Additional Secretary, Mahaweli Development, his deputy. Bandaragoda was specially selected for that post because of his role in promoting Sinhala colonization in the Trincomalee district when he was its Government Agent.

Asoka de Silva announced the formation of the JSSOP to the media and said two tasks had been set for it. The first, he said, was to “coordinate anti-terrorist activities in the districts of Vavuniya, Mannar, Mullaitivu and Trincomalee” and the second was to “to oversee civil affairs such as land settlement.”

In the same media briefing, in which Bandaragoda also participated, Asoka de Silva announced that JSSOP’s first activity would be to carry out a “flush out” operation. He did not elaborate when media sought clarification, taking cover under the mask of ‘military secrecy.’ But the propaganda buildup carried out through the Sun and the Island provided the necessary indication.

Peter Balasuriya’s story that appeared in the Island of 7 October 1983 was headlined, “Gandhiyam Movement’s Squatters to be evicted.” The story said that action would be taken to evict the 50 plantation Tamil families settled by the Gandhiyam Movement two years ago in a land of about 500 acres in the Mullaitivu district earmarked for the settlement of landless villagers under the World Bank scheme. It added that landless peasant families selected by the Government Agent, Vavuniya to be settled in this land were unable to move there due the encroachment by plantation Tamils.

Gamini Dissanayake, staunch supporter of Jayewardene’s effort to defeat the Tamils and his Sinhala colonization policy, defended and furthered Jayewardene’s JSSOP project.

Dissanayake sent his confidant, T. H. Karunatilleke, on 10 October 1983 to report ‘on the extent of the encroachment in the Vavuniya and Mullaitivu districts.’ Karunatilleke reported that large areas in the Vavuniya and Mullaitivu districts were being colonized by the stateless plantation Tamils. The report said they posed a security threat. (see Malinga Gunaratne’s For a Sovereign State for the full report).

The Sun and the Island and their Sinhala sister papers were used for the buildup for the flushing out operation. The Sun screamed on 17 October 1983: Stateless persons encouraged to encroach on state land in the N-E.’ Nearly a quarter of the first page was filled with the decked headlines: Forces and police fear grave security threat – Organized attempt to form Eelam boundary of humans – NGOs pumping money to establish settlements.’

The report, date-lined Vavuniya, charged that hordes of stateless persons of Indian origin were moved into the northeast with the connivance of Thondaman’s Ceylon Workers Congress and taken over by the TULF and the NGOs like Gandhiyam and TRRO which had ‘terrorist’ connections and settled in the border areas to ‘form a human buffer zone enveloping the districts of Batticaloa and Jaffna. The report accused that about 10,000 persons had been thus moved and NGOs like the Norwegian Redd Barna, German GTZ, SEDEC run by the Roman Catholic Church and Sarvodaya were funding the operation.

Tamil Ministers Differ

This report infuriated both the Tamil ministers in the cabinet. Thondaman issued a strongly worded statement and Devanayagam held a press conference in his ministry the next day, 18 October 1983. I wrote the story on Thondaman’s statement and covered Devanayagam’s press conference for the Daily News.

Thondaman, in his statement, strongly objected to the charge that a large number of stateless persons had been moved to the border villages and that was being done with the connivance of the Ceylon Workers Congress. He said plantation Tamils who lived in Sinhala villages had been uprooted during the 1977 riots and some of them migrated to the north and south seeking safety. He reminded the readers that he had not joined the government at that time, and neither he nor the CWC had been involved in the movement of people to the north or the east. He said the government did not take care of the refugees and he thanked the NGOs for helping them. He condemned their recent eviction as inhuman.

Thondaman charged government officials of failure to regularize the settlements in accordance with government policy. Instead, he added, they were trying to drive the people of Indian origin out of their holdings ‘under various pretexts.’ He also accused the police and the security personnel of setting in motion ‘a wave of terror’.

Devanayagam uncategorically told the media that there was no organized move to form a human buffer zone of stateless persons anywhere in the recent past. He called the Sun story an ‘irresponsible piece of journalism’ and warned that it would damage the good work of internationally-reputed NGOs. He accused the press of not showing similar interest in the Sinhala encroachment of Maduru Oya. Devanayagam was at that time engaged in a battle with his own government to protect his own electorate, Kalkudah, from being colonized by the Sinhalese. The Maduru Oya project falls within the Kalkudah electorate.

Gamini Dissanayake took up the battle directly and indirectly with the two Tamil ministers. He was hard on Thondaman because he was his rival in the Nuwara Eliya electorate. He charged that Thondaman was only interested in the wellbeing of his people and not in national security. He said the unauthorized settlements in Vavuniya and the Batticaloa districts were covers for ‘terrorist training grounds.’ He added that youths of plantation families were being trained as terrorists.

To answer Devanayagam Dissanayake sought the assistance of his friends in the Sun. The paper carried a story the next day, 19 October, saying that the people who tried to occupy the Maduru Oya settlements were Sri Lankan nationals who paid taxes. It said the Tamils who were settled in Vavuniya were stateless people. It tried to justify the Maduru Oya invasion by propounding a new theory that Sinhala citizens had the right to encroach on state land!

Jayewardene was not bothered about the opposition from his Tamil ministers. He continued with his plan. In late October he entrusted the task of making contact with the Israelis to his son Ravi, paving the way for the visit of President Reagan’s roving ambassador Vernon Walters.

Walters arrived in Colombo on 7 November evening and held a lengthy discussion with President Jayewardene over lunch the next noon, 8 November 1983, about military assistance. Lalith Athulathmudali and Ravi Jayewardene were present. Parthasarathy arrived on 7 November morning on Jayewardene’s invitation and held a lengthy discussion with him about a political solution. With Walters, Jayawardene discussed ways and means of obtaining Israeli arms and military expertise to defeat the Tamil revolt. With Parthasarathy, he discussed strengthening the powers of the District Councils, which he had offered the Tamils as the basis for a political solution. Parthasarathy at this meeting pressed Jayawardene to agree to the merger of two or more District Councils. Discussing peace the first day and preparing for war the next day, ENLF spokesman Balakumar told the media in Chennai on 9 November, showed Jayewardene’s ‘sincerity.’ “How can we trust a person like that?” he asked.

In Colombo the same evening, Walters evaded answering questions asked by the media about the substance of his talks with Jayewardene. But he took a swipe at Parthasarathy and the Indian peace effort when he said Sri Lanka was capable of solving her problems and President Jayewardene had “all cylinders firing.” He also dodged the question whether he discussed Trincomalee harbour with Jayewardene, saying he would not go anywhere near Trincomalee. Instead, he volunteered, that he, being a ‘history buff,’ visited Kandy.

It was later revealed that Walters did discuss Trincomalee with Jayewardene and obtained his signature on the Voice of America Agreement, the text of which he had brought with him. He had also obtained Jayewardene’s agreement for full diplomatic recognition of Israel.

Encouraged by the shift in the stance in the US’ Sri Lanka policy Jayewardene took action to put his military option into operation. He sent Cabinet Secretary G. V. P. Samarasinghe to a secret destination in Europe to meet top Israeli officials to work out the details about signing an agreement to obtain the services of Israeli intelligence officers. The agreement was signed later that month in New York during the UN General Assembly Sessions.

Implementation of the agreement with Israel ran into difficulties. Muslim ministers M. H. Mohammed and Sahul Hameed opposed the agreement when Jayewardene informed the cabinet about it in January. Muslims launched an agitation against the diplomatic recognition of Israel. Saudi Arabia and Kuwait suspended their funding for the downstream development of the Mahaweli Project. India also signified its strong opposition. Jayewardene was able to bulldoze the local Muslim opposition, but not that of India and the Muslim countries. He backed out of the promise to accord Israel full diplomatic recognition. After much haggling, he permitted Israel to open an Interest Section in the American embassy in Colombo.

The Israeli Interest Section was opened in May 1984. David Matnai was appointed the first head. In August 1984 six intelligence officers from the Israeli intelligence service MOSSAD came to Sri Lanka to establish a new intelligence network against the Tamils.

Mathew’s Efforts

While Jayewardene and his men were busy doing the spadework to destroy the basis of the Tamil homeland, Cyril Mathew, Minister of Industries and Scientific Affairs, another of Jayewardene’s creations, intensified his efforts to turn the NorthEast into a Buddhist homeland. A group of rabid intellectuals mainly from the middle level castes badhu (Mathew’s caste) and karawas were busy discovering the ruins of Buddhist temples and restoring them and settling Sinhala Buddhist families around them. They conveniently hid the well-established fact that those ruins were that of the Buddhist temples of the Tamils. The Eastern coastal belt of Tamil Nadu was Buddhist from Asokan times till the end of Chola period in the 13th Century. And eastern Sri Lanka fell under the influence of Tamil Buddhists. The influence of Tamil Buddhism was present even in the courts of the Anuradhapura kings. The Mahawamsa had recorded several instances of clashes between Sinhala Buddhist monks and Tamil Buddhist monks, referred to mostly as Chola Buddhist monks.

Buddha, 14-15th century, Pattisvaram, India, in Rajaraja Museum, Thanjavur

Pali being the language of Buddhist scriptures and inscriptions, it was easy for Sinhala Buddhist chauvinists to claim Tamil Buddhist inscriptions as belonging to Sinhala Buddhists. The contribution of Tamil Buddhists to the growth and enrichment of the Sinhala language, especially the development of its grammar was great. The influence of the standard work on Tamil grammar Virasolium written by a Tamil Buddhist monk is unmistakably found in the works on Sinhala grammar.

The revival of Saivaism (the Hindu sect that worships Siva) during and after the Chola period resulted in the neglect and destruction of Tamil Buddhist temples and the building of Saivaite temples in their place or premises. Mathew and his men made a big fuss of this. They accused the Tamils of wanton destruction of ancient Buddhist temples by Tamil Hindus and used state funds to destroy Hindu temples and restore the Buddhist temples. They established Sinhalese settlements around the restored Buddhist temples.

Mathew’s campaign backed by Sinhala media gave the ethnic dispute – a Sinhala-Tamil row- a religious dimension. It turned the dispute into a Buddhist – Hindu clash. The Sinhala media built a major story out of the trimming of a bo-tree and of how it was done by a Tamil. The story was often blown up as a Tamil terrorist act of desecration.

The search for Buddhist ruins was the political treasure hunt of that period. That gave another ‘proof’ for Sinhala nationalist to ‘establish’ that the eastern province was the cradle of ancient Sinhala Buddhist civilization. I feel sad that none of the Sinhala leaders or journalists gave thought about the effect their actions would have on Tamil Hindus.

Tamils were aware of the Sinhala Buddhist strategy. They were paid. They were angry. They were helpless. The report I give below appeared in the Saturday Review of August 1982. It reflects the Tamil Hindu sentiments. And when Pirapaharan led the resistance, they welcomed him. The Saturday Review report:

Kuranthan Malai is a quiet peaceful spot in Tamil-populated Mullaitivu with ruins of both Hindu and Buddhist places of worship. It will soon house an exclusive Buddhist vihare and temple and a Sinhala settlement, according to plans drawn up by officials working under the Ministry of Industries and Scientific Affairs.

An ex-Director of a Public Corporation under the Ministry who was also a leading member of the UNP Trade Union – the Jathika Sevaka Sangamaya- is spearheading the implementation of the project. He is assisted by several army personnel.

Several employees of the Ceramics Corporation and the Tile factory of Oddichuddan 20 miles away, have been enlisted to help the implementation of the project. Vehicles and the resources of the corporation which come under the Ministry of Industry are being used for this project.

Hindu statues found in the site have been taken away in Army vehicles, according to the local villagers, as far back as November last year. Kurunthan Malai situated in the Nagancholai Forest Reserve has long been held in veneration by the Vanni Tamils as the dwelling place of the guardian deity, Kurandoor Aiyanar. The building of a Buddhist vihare at the site began several months ago, and some employees of the Tile factory have been engaged in this, with orders apparently to do it unobtrusively without attracting public attention to the building activity.

Following this, some local inhabitants had put up a hut and installed a “Choolam” (trident) on the spot, but Army personnel from the Mullaitivu camp had demolished the hut, thrown away the “Choolam”, chased away some of the Tamil families in the area and had taken away some of the youths in the area for questioning. Since then, a new road has been built through the Nagancholai Forest Reserve, to facilitate accessibility to this site from Oddichuddan.

Three major consequences flow from this move, quite apparently initiated by the Ministry of Industries:

(1) Archaeological sites are being damaged irrevocably, preventing any genuine archaeological research on them in the future; (2) Tamils who have lived in the area for generations are being displaced by new Sinhala colonists. (3) Hindu religious sites are being furtively desecrated thus preventing identification of such sites in the future.

But what seems to be the most vicious attempt – an attempt which might well succeed in the present political circumstances – is a grand strategy to destroy the contiguity of Tamil populations of the Mullaitivu, Vavuniya and the Trincomalee districts.

The Padaviya Sinhala colonies are expanding eastwards in an attempt to connect with the Kokkilai Lagoon area. It is believed that with the pressures from the Mullaitivu Army camp on the northeast, the Tile factory of the Ministry of Industries at Oddichuddan on the North-west – two powerful repositories of State power – a spill over from the Padaviya settlements is bound to occur, as it has been in other instances in the past.

When that happens, the Tamils in three districts will be effectively cut off from each other, thereby not only losing a slice of their traditional homeland but weakened to a position where they cannot withstand further incursions in times to come….

Mathew used the funds, human and material resources of his ministry, the Ministry of Industries and Scientific Affairs, and the corporations that came under it for his campaign to identify the northern and eastern provinces as ancient Buddhist territory. But Jayewardene’s massive scheme to build armed border villages needed huge investments and maintenance facilities. The July 1983 riots had upset the government finances. The Treasury was virtually bankrupt. Attempts were made to obtain World Bank funding by showing the settlements as a project to manage social unrest in the south by settling a section of the landless peasants in northeastern Weli Oya.

(A typo on the map has Manal Aru written as Manu Aru)

I was aware of the preparation of a project proposal for that purpose. The services of two Israeli agriculture experts were employed to modify System L of the Mahaweli Scheme into a dry zone agriculture project for the planting of cash crops like cadju and ‘wonder bean.’ One of the experts was a Professor of Agriculture from Jerusalem University. The other was an agriculture expert involved in the cultivation of the ‘miracle bean’ (jojoba) in Israel’s Negev desert. The attempt failed due to the unexpected attack on the Kent and Dollar farms by the LTTE on 30 November 1984.

The attack on the Kent and Dollar farms is another story and I have already related the basic facts in Chapter 23. Lalith Athulathmudali was appointed Minister of National Security on 24 March 1984. He took over the task of implementing the task given to JSSOP. He visited Mankulam in the first week of May. He went with Vavuniya Superintendent of Police Arthur Herath to the areas where plantation Tamils were settled. I went with the press party. He visited Kent and Dollar farms, two of the several farms developed by Tamil entrepreneurs. Within three months of that visit the inhabitants of these farms were evicted.

Ravi Jayewardene and his group had also become active in “protecting the border” by this time. Ravi Jayewardene visited Israel during 21 June to 1 July. He visited all the border areas of Israel. He looked at the Israeli armed settlements in the West Bank. He studied the strategies Israelis used to establish those settlements and the arming of the settlers to protect themselves from attacks by the Palestinian armed groups.

According to a report published in the Saturday Review a crash land settlement program was launched on the Israeli model in the area north of Padaviya soon after Ravi Jayewardene’s return from Israel. In August 1984, in accordance with a decision taken at a high-level conference in Colombo, the area, which had under the Vavuniya district was attached to the Sinhala majority Anuradhapura district. The administration of the area was brought under JSSOP and the region declared a no-go zone for Tamils.

The region was also renamed Weli Oya. It was not a new name. It was the Sinhala translation of the Tamil name Manal Aaru. Manal or meaning sand was translated to weli. Aaru meaning river was translated to oya.

In the first week of October 1984 Sinhalese government officials and army personnel visited the Tamil settlements in the area and threatened the Indian Tamil settlers to leave. Soldiers assaulted the settlers who resisted. They destroyed their crops and damaged their huts. The Tamil families occupying Dollar and Kent farms were also driven away.

The two farms were taken over by a gazette notification issued on 6 October 1984 and were declared an open-air prison. Lalith Athulathmudali told the media the next week the Open Air Prison Scheme, which had not been in operation for some time due to the lack of land would be revived. He spoke highly about the innovate reformation scheme former Prisons Commissioner J. P. Delgoda had introduced. The scheme was to settle prisoners with a record of good conduct on state land with their families and provide them employment. The program had been abandoned because the Prison Department had not been able to obtain fresh land to continue. Athulathmudali said Kent and Dollar farms had been cleared of illegal encroachers and the property would be used to reunite 150 prisoners with their families.

Sri Lankan commandos

Tamils saw through the scheme. They saw it as a Sinhala intrusion into the Tamil heartland. TULF leader Amirthalingam, who was in Colombo to attend the All Party Conference, reacted with anger. He told the BBC Tamil Service, “We would have welcomed the Open Air Prison Scheme if the prisoners were settled somewhere in the south. Here it is being used as a cover to hide naked Sinhala colonization of the Tamil homeland.”

Thondaman was also angry. He issued a statement condemning the eviction of innocent Tamil civilians. He recorded his protest at a cabinet meeting.

Tamil anger was widespread. “This is pure and simple aggression,” EROS chief Balakumar said in a statement issued in Chennai. Other Tamil militant groups also issued angry statements. But Pirapaharan was quiet. He trained his fighters to give an armed reply.

A TULF delegation led by Amirthalingam and Sivasithamparam met with Jayewardene and Athulathmudali on 13 November 1984 and protested against the government action. They urged Jayewardene to drop the program. They informed them that the Tamils were feeling hurt. The TULF’s standing among the Tamils was being eroded, they complained. “They are asking us: Why are you talking to these people?” Amirthalingam told President Jayewardene.

The TULF followed up the meeting with a strongly worded letter. In that they informed President Jayewardene that prisoners and jail guards who had been moved into the Kent and Dollar farms were harassing the people in the neighbouring villages. They pointed out that the prisoners were indulging in thefts, robbery and rape. Specific instances of rape were also pointed out.

Jayewardene ignored the TULF pleas. And his ministers increased the Tamil fury further with the announcement that 1,000 houses would be constructed along the Mullaitivu coast to settle Sinhala fisher families. Kokkilai and Nayaru were the fishing villages where the majority of the houses would be built, Fisheries Minister Festus Perera said.

The government’s scheme became very clear with Festus Perera’s announcement. Through the Weli Oya scheme, the government wanted to grab the agricultural and forest wealth of the Tamil people. Through the fishing villages network it wanted to gobble the wealth of the ocean adjoining the Tamil areas.

The Armed Reply

And on 30 November 1984, Pirapaharan delivered the armed answer. About 50 specially trained fighters armed with automatic weapons and grenades sped in two buses to the Kent and Dollar farms. One group attacked the Kent Farm and the other the Dollar Farm. They killed 29 in the Kent Farm and 33 in the Dollar Farm, a total of 62 civilians, including three prison guards.

Next night, 1 December, LTTE fighters, led by Captain Lawrence, hijacked the Elf passenger van that plies twice daily to Kokkilai and drove into that fishing village. The time was around 6.30 pm. Some fishermen were standing in groups and talking among themselves. Wives with children joined their husbands in some groups. LTTE fighters fired at them indiscriminately. Manuel Anthony, his wife and their nine-year-old son were in one group. Anthony was hit. He collapsed and died. His son was also hit. His wife picked up her son and ran to a boat. The boy died in the boat. In all 13 were killed and four injured. The Tiger fighters then set off for Nayaru, 15 kilometers away, in the same Elf van.

They reached Nayaru around 8.30 pm. They drove straight to Magailin Costa’s grocery shop firing their automatic weapons. Magilin was the leader of the thugs of the village and a terror to the Tamils. The fighters jumped off the van opposite the shop and flung a hand grenade into it. They searched for Magalin, but she had run away. They shot her daughters Mary Theresa and Mary Margaret. Four were killed and two injured.

At Kokkilai, the people ran towards the sea and hid themselves behind or inside the boats. They came back, according to the evidence led at the inquest proceedings, around midnight. Some of them walked six kilometers south to Pulmoddai in the Trincomalee district to report the incident to the army. The army patrol that rushed to the area was ambushed by the Tigers. They set off landmines and blasted culverts.

At Nayaru, the people fled into the jungle from where the army fetched them the next morning. The injured from both incidents were transported to Anuradhapura and Kurunegala hospitals.

Kokkilai and Nayaru form the northernmost points in the string of Sinhala fishermen’s settlements established along the coast from Trincomalee to Mullaitivu. Most of the fishing families were from Negombo and Chilaw.

I gave a detailed account of this civilian killing by the LTTE, listed as the first Tamil massacre of Sinhala civilians, even in the government-compiled documents (see Massacres of Civilians presented to Parliament by Deputy Minister for Defence Anuruddha Ratwatte on 6 February 1996. It is a document which lists incidents in which nearly 2,900 mostly Sinhalese civilians were killed during the period 1984 to 1996), and the reaction of Thondaman, one of the two Tamil ministers in the Jayewardene cabinet, in Chapter 23. I am repeating these events for two reasons. Firstly, to record the events in their sequence and context and secondly, and more importantly, to record the Tamil reaction to the massacre.

Thondaman welcomed the killing. So did every other Tamil I know of. They did not view that as the killing of innocent civilians. They viewed the murder as the riddance of the torturers of innocent Tamil civilians. More importantly, they viewed it as a fitting reply to Jayewardene, Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake, Ravi Jayewardene and their ilk.

The Dollar and Kent farm killings fortressed, psychologically, the growing conviction among the Tamils that they constitute a different nation. They have to stand up to the Sinhalese if they are to survive as a people. And, Pirapaharan is the only person who can do that.

Next: Chapter 43. The Massacres

To be posted April 15