by T. Sabaratnam, January 7, 2004

Volume 1, Chapter 24

Original index of series|

The Unnoticed Messages

Tamils, through the DDC election, gave two clear messages to the Sinhala leaders, Sinhala people and the world.

The Tamils told them unambiguously, that the Tamils were for a separate state which would restore their racial rights, dignity, safety, security and land, and that they wanted to achieve it through non-violent, democratic means under the leadership of the moderate TULF.

President Jayewardene and his advisors read only the first part of the message and, in their anger, started mauling the TULF for preaching separation. They never attempted a deep analysis of the reasons why the Tamils opted for a separate state or how that problem could be managed.

In their anger and arrogance, they failed to grasp the significance of the second message; the Tamils wanted to pursue the non-violent, democratic path. They also failed to grasp the significant facts that the Tamils had rejected PLOTE’s boycott call and they were not cowed down by PLOTE’s threats.

The Jayewardene government, if it had understood the messages Tamils had given, should have encouraged and supported the TULF’s decision to support the DDC scheme, which gave a self-governing structure with minimal powers to the Northeast. Instead, the government obstructed the working of the DDCs, refused to devolve to any power to them, declined to provide them the necessary funds and, above all, unleashed state terror on the TULF and the Tamil people. The Jayawardene government treated the demand for a separate state as a punishable offence.

Jayewardene was never considered a statesman with foresight and vision. He was regarded by political analysts as a

shortsighted, master political strategist and schemer, concerned with entrenching his power by outmaneuvering his equally shortsighted opponents. He saw in the massive endorsement Tamil voters gave to the TULF a challenge to his political authority and to the Sinhala race. His attempt to weaken the TULF and to give collective punishment to the Tamil people had the opposite effect. He strengthened the Tamil militant groups and pushed the Tamil people into their camp.

Statue of Thiruvalluvar, Jaffna 2014

The burning of the Jaffna town, the cultural centre of the Tamil people, smashing the heads of the statues of Thiruvalluvar, Auvaiyar and Arumuganavalar, the venerated Tamil poets and the Hindu revivalist, the torching of the Jaffna Public Library, the attack on Yogeswaran and the arrest of Amirthalingam were unpardonable crimes that wounded Tamil sentiments. Yet through the DDC election the TULF and the Tamils gave the message they were prepared to cooperate with the Jayewardene government to work the DDC scheme.

The government’s response was to defend the atrocious crimes the police and the army committed. Its minister, Cyril Mathew, justified the burning of Yogeswaran’s house. And President Jayewardene took up the position a month later in an interview he gave to the Indian weekly India Today.

Amirthalingam made a detailed statement in parliament on 9 June 1981, eight days after the burning of the Jaffna Library, when he described the events in Jaffna as the “darkest pages in Jaffna’s history.” Yogeswaran gave a detailed account of his escape when his house was torched by the police. Yogeswaran said he had lost everything. He charged: “You have let loose – the government has let loose – on unarmed civilians, violence unparalleled in any civilized country, during peace time.”

Mathew jumped up to defend the police. He accused Yogeswaran of holding a meeting with the terrorists in his house.

Yogeswaran denied the accusation as a pure concoction.

Manipay member V. Dharmalingham interjected: “It was on the information given by Minister Mathew that his

[Yogeswaran’s] house was burned. He seemed to have given such information to the police and the police burned down the house.”

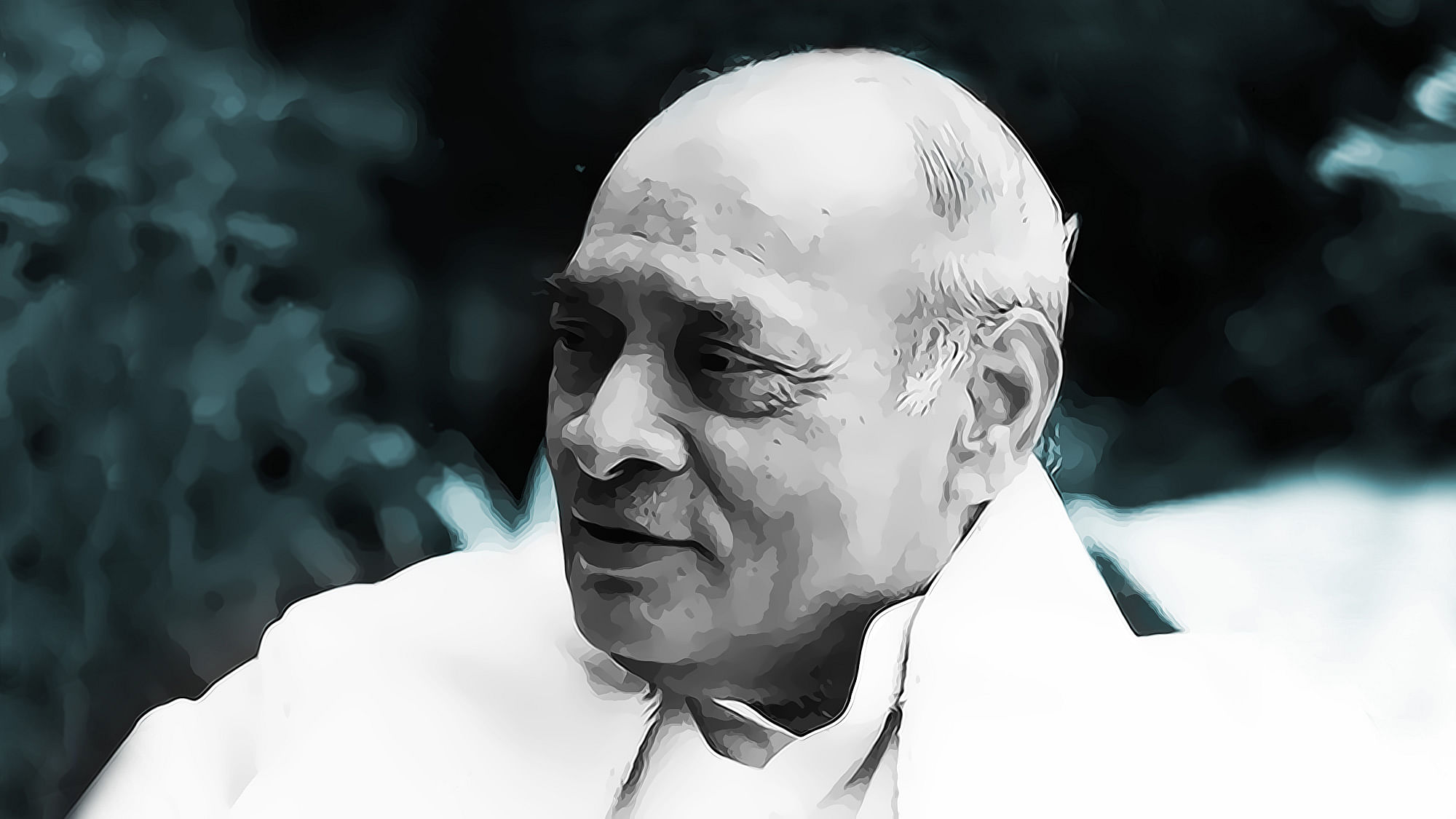

S. Venkat Narayan 2018

A month later, in an interview to S. Venkat Narayan, Senior Editor of India Today President Jayewardene maintained the same position. [ Sept.1-15, 1981, pp18-19]

Venkat Narayan: In Jaffna the people are very upset. The policemen set fire to the 50-year-old library and burnt 96,000 valuable books. They also set fire to TULF MP’s house.

Jayewardene: That’s because they think that he is in touch with the terrorists.

Venkat Narayan: It seems they were trying to catch him so they could kill him.

Jayewardene: Terrorists do that, too.

This interview, reprinted in the Daily News of 7 September 1981, captures Jayewardene’s attitude during that period. He did not repent the burning of the Jaffna Library or Yogeswaran’s house. He did not deny even the police involvement. As Venkat Narayan commented about the next question, Jayewardene was involved in a ‘tit for tat’ game.

The ‘tit for tat’ game took a turn for the worse after Amirthalingam’s tour of the USA, Britain and India, where he made use of the Jaffna events to tell the world that the Tamils were not secure even in their hometowns. He said the riots of 1956 and 1958 had made the lives of Tamils in Sinhala majority areas and in Sinhala-colonized areas in the east insecure. The riots of 1979 and 1981 rendered their lives in their traditional hometowns also insecure.

The government was annoyed with Amirthalingam’s speeches and it got the state media to launch a virulent campaign against Amirthalingam. A hate campaign against the Tamils was orchestrated systematically.

On Amirthalingam’s return, the TULF gave notice for a vote of no-confidence against the government and the government retaliated by giving notice of vote of no-confidence against Amirthalingam, the Leader of the Opposition, an irrational and unprecedented move in the history of parliaments of the world. It was signed by 36 UNP parliamentarians.

The government decided to give priority to the no-confidence motion against Amirthalingam and allocated 23 and 24 of July to debate it. Panadura MP Dr. Neville Fernando moved the motion. Later, after he was sacked from the UNP, Fernando told parliament he was pressurized by Jayewardene to move the motion.

Amirthalingam rose to give a personal explanation. He was greeted with a torrid round of insults. He was called a liar, a traitor, a supporter of the murderous Tigers. Fernando raised an objection on the ground that personal explanations could only be made with the indulgence of the House. Speaker MA Bakeer Markar held with Fernando and declined to allow Amirthalingam to give his explanation. Amirthalingam and the TULF MPs walked out of parliament in protest.

SLFP deputy leader Maitripala Senanayake then raised a point of order and submitted three reasons for why the Speaker should rule the motion out of order. Firstly, he submitted, that the vote of no confidence on the leader of the opposition did not fall within the powers of parliament. It had not happened anywhere in the world. Secondly, the leader of the opposition held his office in accordance to parliamentary convention and he enjoyed the confidence of the members of the opposition. He need not enjoy the confidence of parliament or that of the government members. Thirdly, the motion, even if passed, would not bring any result. Amirthalingam continued to be the Leader of the Opposition even after the passage of the motion.

The speaker dodged the issue and ruled that the objection was raised too late and he could not do anything at that

particular moment, other than to allow the debate to continue. Exasperated, the Communist Party member, Sarath

Muttettuwegama, asked the speaker whether he was running the parliament, or the government members. Amidst loud uproar from the government benches, members of the SLFP and Sarath Muttettuwegama walked out of parliament, thus telling the world loud and clear that Amirthalingam enjoyed the confidence of the entire opposition.

The opposition walkout gave the government members a field day and the state-controlled media was instructed by the Presidential Secretariat to give maximum coverage to the debate. The debate itself clearly revealed the government’s plan: to create in the country an environment of hatred against the Tamil people. The speakers accused Amirthalingam and the TULF of duplicity. The TULF spoke of Ahimsa and Gandhian philosophy in parliament and in the South, but were involved in instigating the youths in the NorthEast to violence and were the brains behind the militant groups, the government speakers accused. They pretended to cooperate with the government, but were slinging mud on the government and the Sinhala people while abroad, they added.

A Amirthalingam and M Sivasithamparam

Thus, the government members charged the Tamil leadership of being double-faced liars and traitors. They operated the bank accounts of the Tigers, Anuradhapura East member Yasapala Herath charged on the second day of the debate. He said TULF president M. Sivasithamparam operated the bank account of the Tiger funds amounting to Rs 400 million sent from United Kingdom, the United States, Norway and Denmark, which Sivasithamparam vehemently denied.

Then the government members discussed how Amirthalingam and other TULF members should be punished for their treasonable acts.

Kundasale MP DM Chandrapala said, “If I were given the power, I would tie him to the nearest concrete post in this building and horsewhip Amirthalingham, till I raise him to his wits. Thereafter, let anybody do anything he likes – throw him into the Beira Lake or into the sea, because he will be so mutilated and I do not think there will be life left in him.”

Ratnapura MP Punchinilame said: “Since yesterday morning, we have heard in this honorable House the various types of punishment that should be meted out to them (Tamil Parliamentary leaders). The MP for Panadura (Dr Neville Fernando) said there was a punishment during the time of the Sinhalese kings, namely, two arecanut posts are erected, the two posts are then drawn toward each other with a rope, then tie each of the feet of the offender to each post and then cut the rope which result in the tearing apart the body. These people also should be punished in the same way… some members suggested that they should be put to death on these; some other members said that their passports should be confiscated; still other members said that they should be made to stand in the Galle Face Green and shot. The people of this country want, and the government is prepared to inflict, these punishments on these people.”

Wilson, in his article, “J. R.: The Man and Politician” that appeared in the Lanka Guardian of 15 September 1992, refers to the incident where Punchinilame discussed with Jayewardene the arecanut pole punishment and says the president had dismissed it, saying those things were unheard of in contemporary times.

The no-confidence motion was passed on 24 July 1981, with 121 votes in favor and two abstentions. Minister S.

Thondaman and Deputy Minister of Justice Shelton Ranarajah abstained. Thondaman also spoke against the motion. He gave a prophetic warning: Do not weaken Amirthalingam or the TULF. If you weaken a democratic party extremism will grow.

Jayewardene or his advisors were not prepared to listen. Their strategy was to weaken the TULF, destroy the militants militarily and to make the Tamils accept whatever concessions they give on bended knees. That did not happen.

Annaikoddai Attack

Three days after the passage of the no-confidence motion – another historic humiliation of the Tamil people – PLOTE militants, led by their leader Uma Maheswaran and his lieutenant Sundaram, attacked the Annaikoddai police station, nine kilometers outside Jaffna, killed two policemen and removed most of the firearms in the police station, dealing the first blow to Sinhala authoritarianism.

In a well-planned attack, the militants hijacked a van around 10 p.m. on 27 July and drove in it to the police station. Two militants knocked at the outer gate. Constable Nazeer opened the gate. He was shot. He died on the spot. On hearing the gunshot Constables Jayaratne, Gurusamy and Bandulasena rushed to the scene. They too were shot. The militants removed seventeen .303 rifles, one sub machine gun, five shot guns and about 1500 rounds of ammunition stored in the station and escaped in the van in which they came. The injured policemen were rushed to Jaffna Hospital where Jayaratna died.

The daring attack on a police station, the first by Tamil militants, the first after the JVP attacks in 1971, shook President Jayewardene and the police. It also shook the defence establishment. The National Security Council met under the chairmanship of Deputy Minister of Defence T. V. Weerapitiya and decided to take two steps. The first was to re-establish the Security Headquarters in Jaffna, The second was to close down the small police stations and to place guards to the bigger ones.

Brigadier Cyril Ranatunga was appointed the Commander of the Northern Province and he set up his office at the Palaly Camp on 29 July 1981, two days after the Annaikoddai attack. Lt. Gen. Denzil Kobbekaduwawas the senior officer posted to assist him. The office was shifted to the Fisheries Corporation building in Gurunagar in the Jaffna town on 11 August.

Ranatunga established an intelligence network and brought the police and military intelligence networks together.

The decision to close down the vulnerable police stations was also implemented immediately. Nine of the 16 police stations in the Jaffna peninsula were closed and permanent guards placed at the entrance of the others. Foot police patrol was restricted and policemen went about in groups in vehicles, often guarded by army trucks. That made a foreign correspondent who toured Jaffna remark that the police had abandoned their law and order maintenance function.

The Annaikoddai attack incensed Cyril Mathew. He rang the President. “Leave that to me,” was the curt reply he got.

Mathew was not prepared to leave it at that. Next morning, 28 August 1981, he wrote this letter to the President:

Your Excellency!

You are bending too far backwards in your anxiety to satisfy the TULF and induce them to a settlement. I am afraid if you continue to bend any more you will very soon loose your balance and fall on your back; then the TULF will not even turn to look back. They will look around to deal with the next party in power.

Signed: Cyril Mathew

Mathew’s accusation about the President’s anxiety to satisfy the TULF was the result of his failure to induce him to convert parliament into a court and to pass sentence on Amirthalingam. The constitution provides for such an exercise.

Jayewardene was not pleased with Mathew’s letter. He demanded a written apology, which Mathew did. Jayewardene was very careful in picking his men and assigning them their tasks. Mathew’s role was to keep the Sinhala extremists satisfied.

In selecting him Jayewardene saw to it that he did not outgrow his role. He knew that Mathew would not be accepted as a Sinhala- Buddhist leader by the Buddhist clergy because of his caste. He was not from the high Govigama caste. In fact, the Maha Sangha resented his role as a Sinhala- Buddhist leader. He was never made the Minister of Buddhist Affairs.

Mathew and other Sinhala communalists whipped up the anti- Tamil frenzy in the country. Mathew bought 20,000 copies of the Hansard, which carried his speech on the vote of no confidence and sent them to temples, police stations, army camps, government offices and public organizations. With the report of the speech he sent a map which showed the number of sacred Buddhist places that would be lost if the Tamils achieved Eelam. Posters in Sinhala, which said, “Sinhala People!

Rise up against the Dravidians!” were plastered all over the country. Mathew also urged the Sinhalese to colonize Tamil areas to safeguard the Buddhist Temples. Government members spoke of the need to inflict collective punishment upon the Tamils.

Rural Development Minister Wimala Kannangara told a meeting: “If we are governing, we must govern. If we are ruling, we must rule. Do not give into the minorities. We are born as Sinhalese and as Buddhists in this country. Though we are in a majority, we have been surrendering to the minority community for four years. Let us rule as a majority community.”

Anti- Tamil feeling surged among the Sinhalese. There were signs of a riot. The TULF leaders immediately condemned the Annaikoddai attack. They called the killing of the policemen senseless. That failed to defuse the situation. When the body of Constable Jayaratne was taken to Ratnapura, the 1981 riots broke.

1981 Riots

Gangs of Sinhala thugs looted and burnt Tamil-owned shops and houses in the cities of the gem mining area of Ratnapura, Balangoda and Kahawatte, the coastal areas north of Colombo and the border villages in the Batticoloa and Amparai districts. Looting, arson and killing then spread to the rural interior. In the hill country, crowds armed with clubs, iron rods, bicycle chains, swords and knives roamed the estates burning, pillaging, looting and killing. Police and army units stood watching, often encouraging the rioters. In the eastern border villages, entire villages were burnt down. People ran into the forests to save their lives. They then took refuge in government schools and Hindu temples. Over 25,000 Tamil plantation workers were rendered homeless in the hills and over 10,000 villagers were made refugees in the east.

An angry CWC leader Thondaman and general secretary Sellasamy barged into a top level security meeting Jayewardene was presiding over at his Ward Place residence on 17 August morning and told him that Sinhala mobs were attacking plantation workers and if they could not stop this, he, Thondaman, would do it. Jayewardene, who was with his top security officials- Deputy Defence Minister TB Weerapitya, Defence Secretary Colonel C. A. Dharmapala, Coordinating Secretary General Sepala Attyagalle and Inspector General of Police Anna Senivaratne- tried to cool down Thondaman, saying they were discussing just that.

Thondaman, who had telephoned Jayewardene and the others who were present there several times requesting action, was blunt. He said: I have phoned every one of you several times. No action had been taken. Things have worsened. Mobs are going around attacking plantation workers. They are being singled out and killed. We have evidence that rowdies and thugs are covertly enjoying the patronage of powerful personalities in the government. If you cannot put an end to this, say so. Then the people themselves will take the necessary actions for their safety and security.” Jayewardene took personal control of the situation in the hill country. Police and army units moved in and restored order.

The attack on plantation Tamils caused ripples in Tamil Nadu and India. On 19 August 1981 Tamil Nadu parliamentarians drew the attention of the Indian government to the crisis through a “Calling Attention Motion” in the Lok Sabah (the Lower House). Foreign Minister PV Narasimha Rao told the House the violence had originated in Jaffna during the DDC election and, following the Annaikoddai attack, it had spread to Colombo and to the estate areas in central Sri Lanka.

“The main victims are the Tamils, the majority of whom are workers in the estates. There have been a number of deaths and numerous incidents of arson, looting and violence. Several thousands of estate workers have been forced to abandon their homes,” he said.

Foreign Minister PV Narasimha Rao

He added that the Sri Lankan government had declared an emergency and was trying its best to bring the situation under control. “As the situation in the country is not stable, and as confusion prevails, we have not yet been able to obtain detailed information as to how many Indian nationals have been affected,” Narasimha Rao said.

“These events are essentially an internal affair of Sri Lanka. Nevertheless, I am sure, the members of the House do share the concern of the government of India, over these developments, since they affect the large number of persons of Indian

origin, and possibly some Indian citizens. It is therefore our hope that the government of Sri Lanka will succeed in its efforts to put an end to the present violence and to restore confidence, so that the present difficulties would soon be resolved and no shadows are cast on the traditional close relations which exist between India and Sri Lanka.”

In the first week of September an incident affecting Indian citizens occurred at Tissamaharama. A tourist bus carrying South Indian pilgrims to Katargama broke-down near Tisamaharama. One Indian pilgrim, Danapathi, a DMK local leader, went in search of a mechanic to repair the bus. He was assaulted and stabbed by a Sinhala gang. He died. The Tamil Nadu State Government condemned the brutal attack and called for a one day work stoppage – a Hartal – in Madras and its representatives in the Rajya Sabah (the Upper House) raised the matter on 11 September.

Rao said both the Sri Lankan president and the foreign minister had expressed their condolences and that arrangements were being made to fly the body back to Tamil Nadu and added: “While the recent developments are essentially an internal matter for Sri Lanka, we have been in touch with the government of Sri Lanka and expressed our concern about the recent developments. The government of Sri Lanka has kept us informed of the turn of events and steps taken by them, stating that they view these events with the utmost seriousness and are determined to restore normalcy.”

Jayewardene toured some of the worst affected areas in Ratnapura and Balangoda districts in the second week of

September on the invitation of Thondaman. Addressing the Tamil refugees Jayewardene said that he was ashamed of those Sinhalese-Buddhist elements who were involved in such beastly acts. He said: “They are animals. They have behaved worse than animals. They have caused sufferings to hundreds of innocent people.”

Tamils were not convinced with the sentiments expressed by Jayewardene. Was it part of a game? He had waited to act till the Sinhala mob had done their damage. News International in November 1981 confronted Jayewardene with this Tamil perception. “They say you are a schemer?” its correspondent asked Jayewardene in an interview. His reply: “I know that they say that I am a schemer, but you cannot be a leader unless you scheme … not in politics or in war or in any human affair. Even a boxer has to scheme, and I was a boxer when I was young. You pretend to hit the face, but you hit the stomach. Oh yes, you have to scheme.”

The August riots were raised in the Rajya Saba again on 18 December. Rao told the House the August violence had

affected several thousand persons of Indian origin. The police had reported seven deaths, 196 incidents of arson, 35

incidents of looting, 15 incidents of robbery and seven incidents of injury, he said. He added: “The government of India has been in close touch with the government of Sri Lanka and have expressed our concern to them. It is understood that steps taken by the government of Sri Lanka to maintain law and order have yielded positive results.”

Rao had quoted the official statistics provided by the Sri Lankan government. Brian Eads reporting in the London Observer of 20 September 1981 wrote: It is clear that the violence in July and August, which was directed against Sri Lanka Tamils in the east and south of the country, and Tamil estate workers in the central region, was not random. It was stimulated, in some cases organized, by members of the ruling UNP, among them intimates of the President. In all, 25 people died, scores of women were raped, and thousands were made homeless, losing all their meager belongings. But the sublime madness, which served the dual purpose of defeating Tamil calls for Eelam, that is a separate state, and taking the minds of the Sinhala electorate off a deepening economic crisis, is only one of the blemishes on the face of the island.”

Next: Chapter 26: The First Attack on the Army

To be posted on January 14

###

Volume One

Chapter 1: Why didn’t he hit back?

Chapter 2: Going in for a Revolver

Chapter 3: The Unexpected Explosion

Chapter 4: The Tamil Mood Toughens

Chapter 5: Tamil Youths Turn Assertive

Chapter 6: Birth of Tamil New Tigers

Chapter 8: First Military Operation

Chapter 9: TNT Matures into the LTTE

Chapter 10: The Mandate Affirmed

Chapter 11: The Mandate Ratified

Chapter 12: Moderates Ignore Mandate

Chapter 13: Militants Come to the Fore

Chapter 14: The LTTE Comes into the Open

Chapter 15: The Ban, J.R.’s Gift

Chapter 16: Wresting Weapons from the Enemy

Chapter 17: Sinhala-Tamil Tension Mounts

Chapter 18: Tamils Lose Faith in Commissions

Chapter 19: Balasingam Enters the Scene

Chapter 20: Jaffna Turned Torture Chamber

Chapter 21: The Split of the LTTE

Chapter 22: The Burning of the Jaffna Library

Chapter 23: Who Gave the Order?

Chapter 24: Tamils Still Back Moderates

Chapter 25: Parliament Discuses Ways to Kill Amir

Chapter 26: The First Attack on the Army

Chapter 27: Amirthalingam Taken for a Ride

Chapter 28: RAW Meets Pirapaharan

Chapter 29: The Indian Interest

Chapter 30: LTTE Guerrillas in Action

Chapter 31: The Death of the First Hero

Chapter 32: The Return of Pirapaharan

Chapter 33: Knocking Out the Base

Chapter 34: Tamils Follow Militant Leadership